Media | Articles

The 1932 Graham Blue Streak was an innovative marvel

America’s automotive history is rich with the exploits of Erwin George Baker, an early-20th-century swashbuckler who set scores of speed and distance records with machines as diverse as Indian motorcycles; cars from Stutz, Cadillac, and Wills Sainte Claire; and even a Buick truck. The most memorable drive by the man known as “Cannonball” Baker was his 1933 cross-country dash in a Graham Blue Streak Eight, completed in an astonishing 531⁄2 hours. The record stood for nearly four decades.

Baker’s blast across the United States, on the many unimproved roads of the time, established an image of power and durability for Graham and its new eight-cylinder engine, but performance was hardly the Graham’s only distinction. The company also introduced a bonanza of styling and engineering innovations that changed an otherwise staid industry.

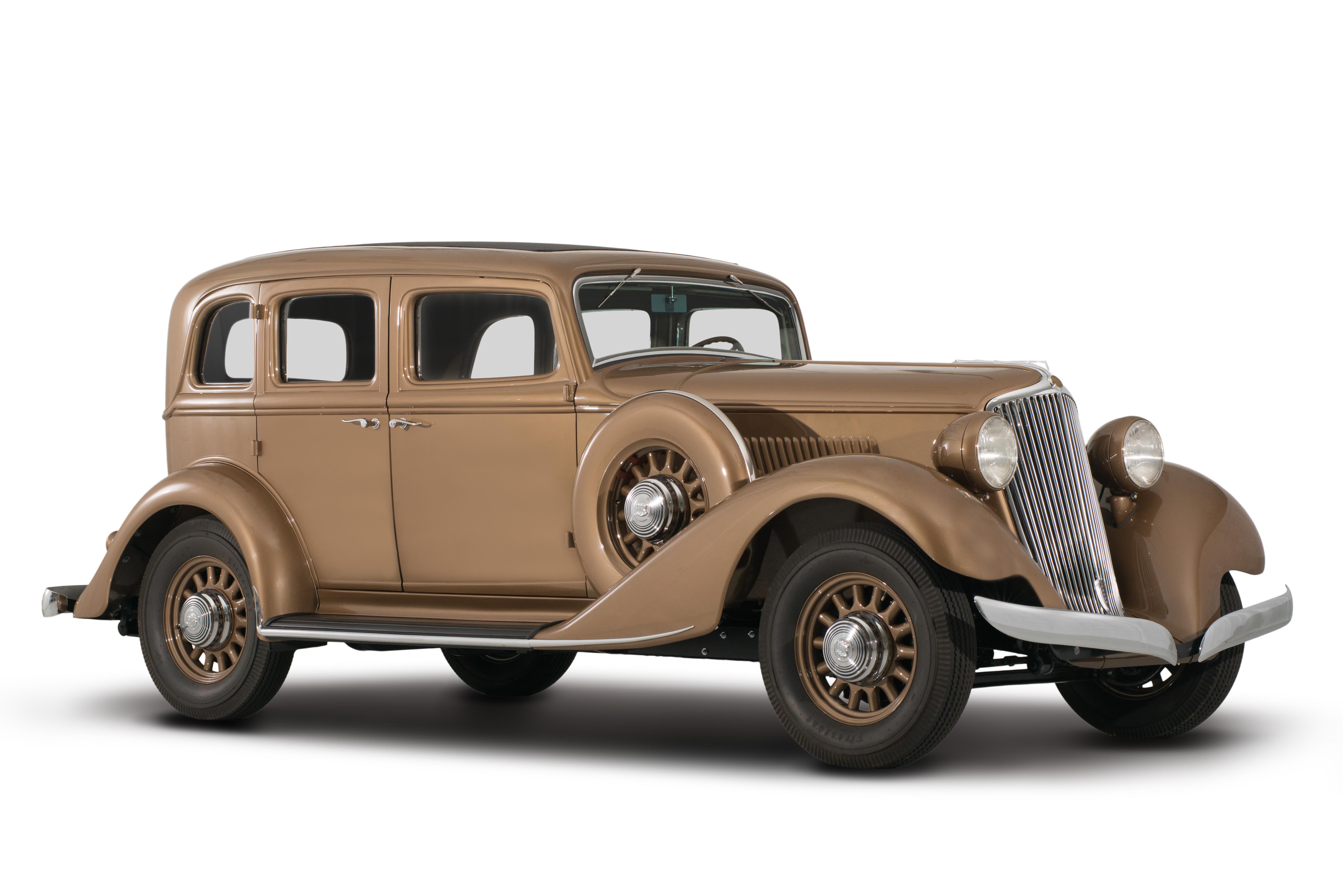

Joseph, Robert, and Ray Graham formed their company after selling their truck-building operation to Dodge in 1926 and, in 1927, taking control of the Paige-Detroit Motor Car Company. The brothers sold more than 73,000 cars in 1928, but four years later, at the height of the Great Depression, they needed a bold new model to turn around their sinking fortunes. The scholarly Amos Northup, a pioneer of streamline design who worked for Murray, a Detroit-based supplier of body stampings, came to their rescue for the 1932 Blue Streak Eight. In an era of styling conventions defined by upright grilles and cycle fenders, Northup’s sloped-back grille and skirted fenders were a breakthrough. The fenders wrapped down from their horizontal surfaces to hide the inner wheel-well panels (and the mud that collected there) while creating a picture frame to showcase the wheels themselves.

Only about 13,000 of the new sedans, coupes, and convertibles sold, but competitors took note. By 1934, nearly every new car in America had skirted fenders in place of what previously had been little more than planks over the front and rear tires.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“Northup was an advocate of harmonious design,” says Mark Gessler, president of the Historic Vehicle Association. “The cars were almost monochromatic, with headlight housings painted the same color as the body rather than being chrome plated. The elements were conveyed as a singular form.”

Northup’s design work for Graham was inspired by the advances in aeronautical design that were happening in the 1930s. In fact, Gessler says, Graham, with the Blue Streak, was the first automaker to test in a wind tunnel. Functional streamlining became a counterpoint to the styling embellishments seen on everything from automobiles to pencil sharpeners to radios and locomotives in the 1930s. Even at rest, the Graham Blue Streak projects a sense of speed.

The Graham’s new chassis also in influenced the Blue Streak’s styling.The rear axle passed through an opening in the “banjo” frame, so called because of that area’s profile, and the rear springs were relocated outboard of the frame rails, rather than directly underneath them. The Graham rode lower as a result, and the frame was masked from sight.

This Graham Blue Streak Eight is the 19th car documented for the National Historic Vehicle Register. It belongs to the NB Center for American Automotive Heritage in Allentown, Pennsylvania, which purchased it from the second owner in 2010 with just 26,000 miles on the odometer. It was always a Pennsylvania car, and it was all Keith Flickinger, the NB Center curator who oversees restorations, could do to find a speck of original paint on the body. The exterior was covered in surface rust, but the decay had not perforated any body panels. Flickinger found a usable sample under a doorsill and discovered the Blue Streak was distinguished from its competitors by its iridescent paint finish. Replicating the paint was the real test.

The Graham factory mixed fish scales into the paint to achieve the Blue Streak’s sparkle. Today’s metallic paints use mica particles, but according to Flickinger, the mica flakes now are too large. The solution: Grind them to a finer size and then strain them through a nylon stocking to eliminate larger flakes—a process he repeated 25 times.

Flickinger and his team treated the body panels with metal-etching primer, sprayed each with polyester filler, and block-sanded and primed them before applying paint. The heavily pitted grille went to a plating shop in Ohio three times for its copper base coat, followed by trial fittings, before the final chrome layer was applied. The Graham, like all cars restored at the NB Center, got a final shakedown test on NB’s own track before the body panels were reinstalled. Despite these measures, Flickinger goes to great lengths to avoid over-restoration and believes that cars are meant to be driven, not just admired. “It drives exactly like new,” he proudly said.

I step into the Blue Streak on a wintry afternoon in Allentown. A firm poke at the floor-mounted starter button cranks the engine to life, no choke required. Thee inline-eight settles into a relaxed, whispered idle before I pull out of the museum driveway. There may be a mere 90 horsepower on tap, but the long-stroke engine pours out torque. Stalling is not a concern.

Nor is keeping up with today’s traffic, although finnding the next gear in the three-speed Synchro-Silent transmission sometimes requires a second try. The Graham’s steering is s-l-o-w, in part because of its 123-inch wheelbase—about the same as that of a modern Mercedes S-class—and also because it’s geared to compensate for a lack of power assist. The Blue Streak Eight demands commitment. The brakes, all hydraulic, are similarly casual: Push firmly or push gently, and the Graham slows at about the same rate. Two ahead-of-their-time Graham features not tested on this drive: dash-controlled freewheeling, which allows the Graham to coast and save on gas, and dash-regulated shock absorbers, which stiffen or soften the ride depending on road conditions.

Nonetheless, the Blue Streak Eight is a thrill to drive, and I quickly imagine that I could open the navigation app on my cell phone and the Graham and I could duplicate Cannonball Baker’s feat, this time on roads far smoother and better marked.

Note: An earlier version of this article, published in the May/June 2018 print edition of Hagerty magazine, omitted credit for restoration work performed by Gardner Restorations in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, before the car’s completion at the NB Center for American Automotive Heritage. Click here to subscribe to our magazine and join the club.