Media | Articles

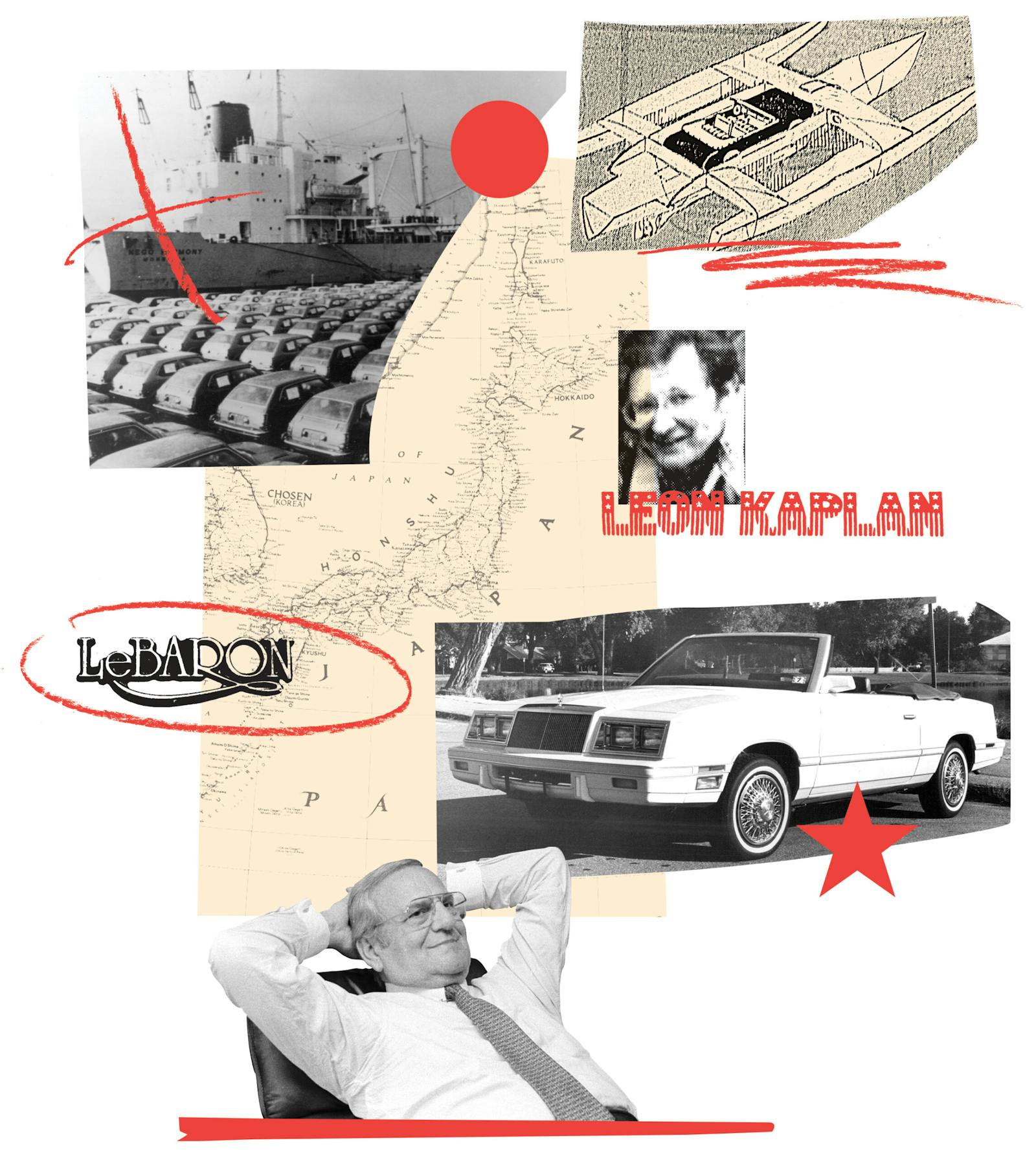

A legendary record hydroplane returns to the water

The late 1930s was a time of enormous advances in maritime engine and hull design, yet the history is strangely obscured and rarely celebrated. So it’s particularly noteworthy when that history does resurface, as is the case with the Blue Bird K3, a 23-foot, single-engine, stepped-hull, Lloyd Unlimited Class hydroplane. After a 22-year family restoration that began in a converted chicken shed, Karl Foulkes-Halbard returned the finished Blue Bird to the water, where it belongs.

On September 2, 1937, Sir Malcolm Campbell piloted Blue Bird to 129.5 mph on Lake Maggiore in Switzerland (the other end of the lake is in Italy). That beat Garfield Wood’s 1932 record of 124.86 mph, set in his 5000-hp, four-engined, conventional-hull, Miss America X on the St. Claire (Michigan) River.

To give an idea of the courage required to hit such speeds at the time, consider this passage from Huberty Scott-Paine, who wrote in the 1934 Batsford Book of Speed on what it was like to set a water-speed record in a single-keel boat. Scott-Paine and his intrepid mechanic, Gordon Thomas, piloted a Napier-engined, aluminium-clad Miss Britain III at over 100 mph on Southampton Water:

20171221135808)

20171221140017)

“There is no question in my mind that the most difficult, the most treacherous, and the most uncertain of the… elements as regards speed, is the water,” he wrote. “I know of no worse condition than running fast along a beautiful mirror-like piece of water, and encountering a rise that you have been unable to see… You get a terrible feeling of climbing into the air out of the water, the last fraction of it being affected by the boat, which has left the surface, being wound round the propeller by the torque reaction.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Eeek! Mention leaving the water and it’s hard ignore those horrific pictures of Campbell’s son, Donald, on his final, fatal run in Blue Bird K7 in January 1967. The boat flipped at 310 mph on Coniston Water in the British Lake District. Chasing records on water is a risky pastime, which perhaps explains why Foulkes-Halbard has so far kept K3’s speed down below 45 knots (52 mph).

So what’s it like to taste such raw speed? Campbell answered that very question in the Batsford book, also teaching a generation of school kids about eclipsing 300 mph, albeit on land, in his car (also named “Blue Bird”) at Daytona. The same Rolls-Royce engine from his car powered the Blue Bird K3 boat.

“Now comes an awful fight,” the speed king wrote. “Blue Bird is snaking this way and that. We hit a bump. I see the needle of the revolution counter vibrating badly, and I know I am getting tremendous wheel spin. Now more that ever, there is a fight to keep the car straight.”

I ask Foulkes-Halbard the same question across his kitchen table, his Labrador retriever panting at my feet. “So you’re lined up, the engine’s warm, the mags are on, and you’re ready to go,” I begin. “You press the button, and when the engine fires you move the throttle forward, and pretty soon you’re going pretty quickly…”

He describes the sensation, eerily similar to what Campbell experienced in 1934 on land.

“At first the stern goes down and the bow comes up,” he says, “but pretty soon you overtake the bow wave and you’re on plane. Then it does various things; it slides and skids around almost as though the back wants to overtake the front; it prop-walks you to starboard; and it runs at a slant with the torque of the prop. You can’t correct it—you have to drive through it, but it’s not for the faint hearted. Bloody hell, it’s a fast boat.”

A whole lot of engine

You need to know that when Foulkes-Halbard pushed that button in September, it was with almost a quarter of the power available to Sir Malcolm. Behind the cockpit of the restored K3 sits a 650-horsepower, 1500 lb-ft, 27-liter Rolls-Royce Meteor tank engine, a development of the Spitfire’s Merlin unit, naturally aspirated with reasonable spares availability, Foulkes-Halbard bought a starter motor for £350 (about $470) and a fully reconditioned ex-Ministry of Defence Meteor engine costs about £10,000 ($14,390).

20171221140050)

20171221140456)

What Sir Malcolm had roaring in defiance behind him, however, was something much more expensive and completely different. The K3’s original engine was the Rolls-Royce R-Type, a experimental, supercharged monster producing around 2530 hp, with its twin-impeller blower boosting at about 18 psi. Just 19 of these V-12 units were built, destined for aeronautical record breaking in the nose of the Supermarine S6 and 6b, Reginald Mitchell’s predecessor of the Supermarine Spitfire. Blue Bird K3‘s engine was designated R37 (all given uneven production numbers). Designed by Arthur Rowledge and based on the Buzzard engine, this 27-liter lump had the same capacity as the Buzzard, along with its six-inch bore and 6.6-inch stroke. It weighed just 1640 pounds and was shaped to aid the aerodynamics of the seaplane racers.

It was also immensely popular with record breakers: the Campbell-Railton Blue Bird, George Eyston’s twin R-engined Thunderbolt, and boats Miss England II and III and Blue Bird K3 and K4. These were very expensive, bespoke hand-built engines, with a rebuild service schedule that called for a complete strip down and rebuild after every six hours of running.

“Oh, and the engine we owned, had been overheated twice,” Foulkes-Halbard says, “so there wasn’t much of a discussion when it came to what we should put into the K3.”

What he doesn’t say is that in early 25-minute tests, the R engine would eat 71 gallons of pre-heated castor oil, most of it thrown out of the exhausts (the test staff had to drink milk to mitigate the laxative effects of the lubricant), and it also drank 95 gallons of special brew fuel merely to warm itself up. If the Meteor is less powerful, it is also certainly cheaper to run.

Post-record ownership

The history of how this extraordinary craft ended up in a converted chicken shed at the back of an ancient manor house nestled in the Sussex Downs is one of typical British grit and determination. Foulkes-Halbard explains that soon after it had achieved its third record breaking run at 130 mph in 1938 at Lake Hallwil in Switzerland, Sir Malcolm retired the boat and sold the hull to a car dealer, keeping the R-Type engine and drivetrain to fit into the K4 three-point hydroplane which replaced K3.

Blue Bird was displayed in a dealership on London’s North Circular Road, where it survived the attentions of the German Luftwaffe in World War II, but by the end of hostilities it had begun to look quite scruffy. As Foulkes-Halbard points out, with a 23-foot long, 9.5-foot wide hull, this is not an easy craft to store, even with the custom trailer it still sits on. He recently was sent some pictures of Blue Bird in the mid-1960s, showing it stowed in the open in a parking lot, with the deck covering starting to peel and leak, and the cockpit open to the elements.

20171221135736)

20171221135843)

“This was probably the most dangerous time,” he says. “It’s big, it’s in bad shape, it’s in the way, and it’s difficult to move. This is where it was closest to being broken up.”

But the romance of the Blue Bird and Campbell names still had some pull, and the old boat was rescued by a Lord Bolton, who got it under cover, stored it, and did some restoration work. In 1974, it was in turn purchased by First Leisure Ltd., which became theme-park operator Thorpe Park, based near a series of flooded gravel-pit lakes to the West of London. Blue Bird was gussied up and put on display again, but the nature of the amusement park business was changing to themed rides, and Blue Bird was up for sale again.

It was Karl’s father, Paul Foulkes-Halbard, who—tipped off by motoring historian David Burgess-Wise that the boat was for sale—had the vision to buy the boat and the two R engines that Campbell had at his disposal from other sources.

“It was an enormous amount of money for what we were getting,” Karl Foulkes-Halbard says with a smile. “We showed K3 for a year outside the Manor, and then the following year it went under a marquee.”

This was the late ’80s, and Paul and Karl faced an enormous decision. Clearly some work had to be done on the hull and they weren’t sure whether they should restore it to working order or merely as a static exhibit. They decided on the former.

I met Paul Foulkes-Halbard in the mid-’80s and remember suggesting that he was stark-staring bonkers. “I think the only one who thought it could be done was my dad,” Karl says, grinning at the thought.

A lengthy restoration

In 1992, the hull was entrusted to Ken Pope, a master yacht builder and cabinet maker. He started the restoration by stripping the hull down to its hog and stringers, when the extraordinary quality of Fred Cooper’s design and Sanders Roe’s original build quality shone through. While both rock elm and aluminium runners were replaced for safety, most of the boat’s framing was kept. The complex triangulated double-diamond structure was restored and resheathed in plywood and doped fabric including the decking.

“You could call it a three-year, sympathetic-but-very-thorough restoration,” says Foulkes-Halbard, who was dragooned by his father into helping strip the boat. “I’ve always felt confidence in the hull because I know what’s gone into it.”

20171221140431)

20171221140151)

With a decision on the lighter, cheaper, and more practical Meteor engine already made, the next problem was the transmission, which had to be created from scratch. The team showed its ingenuity by creating a 3:1 step-down ratio ‘box out of a semi truck hub and having a complete dog-clutch gearbox fabricated from scratch. Karl explains that it is a single-speed transmission, and you can’t change gears with the engine running. When you start the engine, the propeller is either disengaged or engaged. In the case of the latter condition, “once you’ve started, you’re off,” Foulkes-Halbard says.

The engine and transmission were fitted between 1996 and ’98, but Paul’s death from a stroke in October 2003, at the age of just 66, meant the project was on hold for a good while. Karl took up possession of the old boat and cajoled his skilled team of engineers and volunteers to continue to methodically work through the job lists, which took several years. “We did the first floatation test on 20th September 2011, Dad’s birthday,” he says.

Almost a decade after Paul’s death, in June 2012, the work was complete. Despite a severe drought, which had depleted Bewl reservoir on the border between Kent and East Sussex, the renovated Blue Bird was returned to the water there. On June 26 at 10:30 a.m., Karl pressed the button on a warmed engine. “She fired, and for the first time in 75 years, she was underway,” he says with a flush of pride. “I did one run on one-third throttle, and it was at that point I realized that this was one hell of a fast boat.”

It was an amazing moment, but it proved something of a false dawn as the team then struggled through five years of mechanical gremlins and the consequences of failing to understand the sheer power of water. Propshafts, transmission bearings, a carb fire at the Henley regatta, shear pins that didn’t work and some that did, and a complete rebuild of the carburetors all took years of head-scratching toil. The team learned to start the boat with the engine at idle speed so as not to overstress the transmission. And not to turn the boat at the end of the run because of the strain on the rudder.

Three months ago, back at Bewl Water, Foulkes-Halbard pressed K3‘s button again in front of the press, as well as the family and friends of all who have been part of the project.

“What amazing day,” Foulkes-Halbard says. “We had a 100-percent start rate. It ran like a dream.”

20171221140519)

The historic boat’s future

So what next? Foulkes-Halbard says that restoring this old hydroplane to running condition has a caretaking benefit, in that it has to be maintained in tip-top condition rather than allowed to moulder in the back of a car park. Although he’s adamant that Blue Bird won’t run at record speeds again. He tells the story of commander Peter Du Cane, hull-design expert and test pilot for Vospers, who was asked to test drive K3 in 1938 after Sir Malcolm thought there might be a problem with the boat. Du Cane’s advice was the hull was probably past its best and advised not to do any more record breaking in it. With his typical stubborn gung ho, Sir Malcolm took it straight out and set a new record.

“Sir Malcolm was a very courageous and very skilled pilot,” Foulkes-Halbard says, “but this old boat’s got nothing to prove.”

So a gentle life of demonstration runs beckons, and next year Foulkes-Halbard plans to take Blue Bird to Italy to run it on Lake Maggiore on the anniversary of its last record-breaking run. He reckons there’s a bit more speed than he’s seen at the helm, but the point is to let people see it and appreciate it as a working piece of history.

“Dad would have given the thumbs up,” he says. “But as much as it’s a homage to him, it’s also a tribute to Leo Villa [the Campbell’s legendary mechanic/chief engineer], who Dad knew, and Sir Malcolm and the boys who’ve restored it.”

20171221140544)