Media | Articles

The mid-engine Mustang that never was

Nearly 55 years ago, on Oct. 7, 1962, as thousands gathered to watch the U.S. Grand Prix at New York’s Watkins Glen, all eyes turned to a Ford transport trailer emblazoned with the name that would one day become an automotive icon: Mustang.

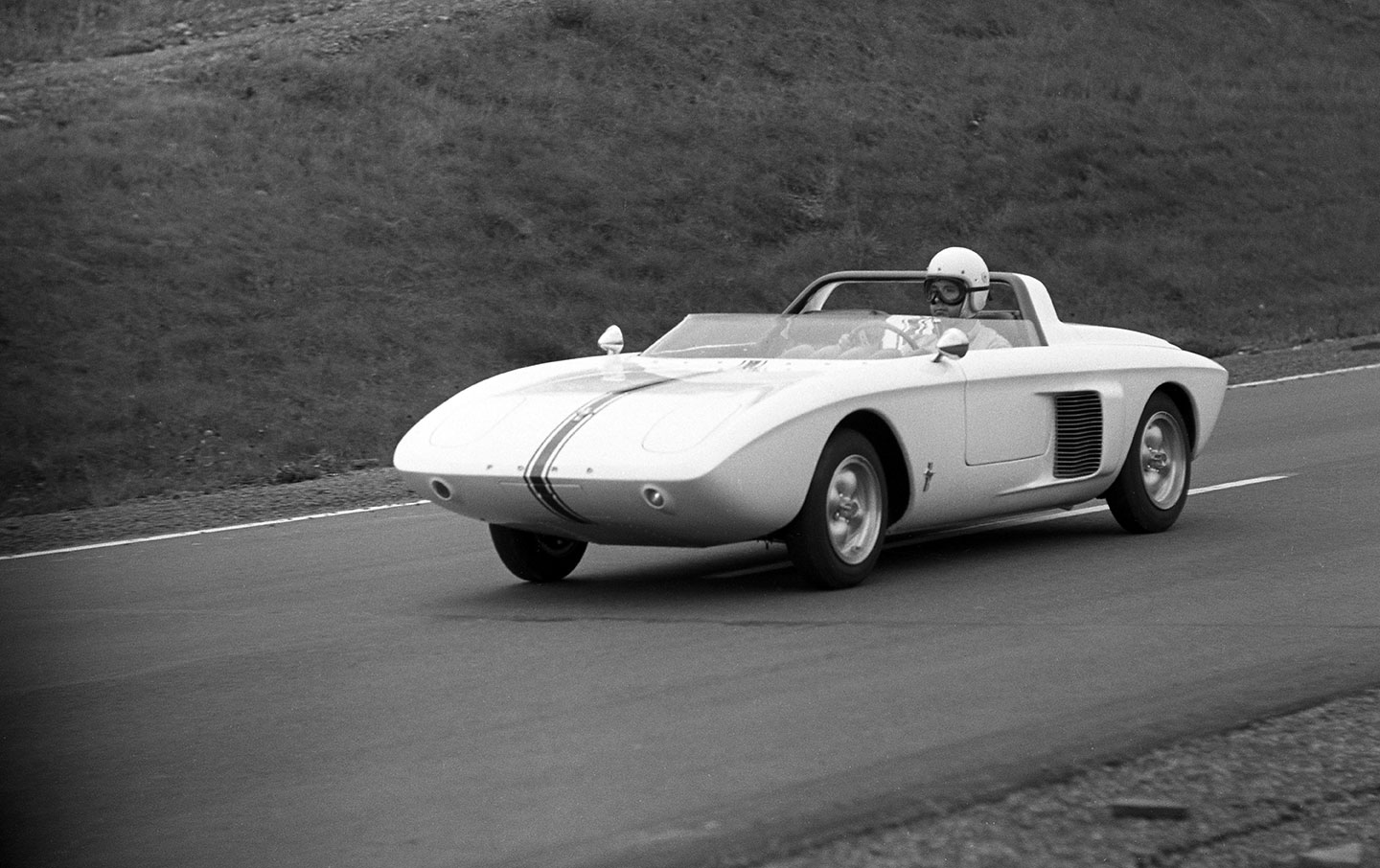

The crowd cheered as a small, radical mid-engine sports car rolled down the ramp, and the applause grew as race driver Dan Gurney drove the diminutive 154-inch long roadster onto the track. Gurney took a high-speed pass in front of the grandstands and proved that the Mustang was indeed an actual car, not a gimmick. Or was it?

The sports car’s introduction came just months after the Shelby Cobra became a public sensation. So when a Ford press release described the original Mustang as a “high-performance personal automobile (that) could fit the mass sports car market,” car buyers naturally assumed the automaker was serious about building a two-seater to compete with small European roadsters like the MGA and Triumph TR4. Except there was never a plan to put the car into production.

Initially conceived as a “what if” exercise in spring 1962, the Mustang roadster—later renamed Mustang I—became the quintessential publicity stunt to generate interest in Ford’s “Total Performance” racing program and, by extension, its performance-oriented production models.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

One month before the sports car’s debut at Watkins Glen, Henry Ford II gave Ford Vice President and General Manager Lee Iacocca the green light to build a sportier, Falcon-based four-seater that had been on the drawing board in various forms since 1961. The car’s design was locked down earlier that summer, but it lacked a name. After the public’s favorable reaction to the two-seat concept car, the decision was easy. By November 1962, Ford’s sporty new model would be called the Mustang.

Ford executive stylists John Najjar and Jim Sipple are credited with the two-seater’s design, and Najjar named the car after the P-51 Mustang fighter plane from WWII. But connecting the roadster to a breed of wild horses seemed more logical for a sports car. Designer Phil Clark created the iconic logo of a galloping horse over a red, white, and blue vertical bar.

Ford contracted race car builder Troutman-Barnes to construct Mustang I. The California firm fabricated the tube-frame chassis and aluminum body over the summer. But the drivetrain, or “ponypack,” as Ford called it, was actually an off-the-shelf piece—a shelf unknown to most outside Ford. The unusual 1.5-liter V-4 engine and four-speed transaxle came from a Ford-developed, front-wheel-drive compact called the Cardinal. Iacocca had cancelled the model for the U.S. market and sent it to Ford’s German branch, which built it as the Taunus P4.

For Mustang I, tweaks to the 60-degree V-4 bumped output from a stock 65 horsepower to a claimed 109 hp—plenty for the 1,500-pound roadster. (The V-4 was also used by other European Fords, as well as some Saabs, including the Sonett sports car.) Tubular A-arm front and rear suspension followed race car practice, and the Mustang rode on tiny 13×5-inch magnesium wheels. The sparse cockpit featured a low-profile windshield and non-adjustable bucket seats; the steering wheel and pedals adjusted. The mid-engine layout, gaining momentum in the racing world at the time, would not debut in a production road car until France’s Matra Bonnet Djet, which was first available in 1963.

Even Ford insiders who developed the original knew two-seaters had limited market potential. The Chevrolet Corvette and Ford’s own 1955–57 Thunderbird were proof of that. After the Edsel debacle, Ford was on a roll with the successful Falcon and Fairlane, and it was looking for more profits, not niche cars.

Following its debut, the Mustang I sports car and its non-functional fiberglass twin toured car shows and college campuses as part of Ford’s “Total Performance” promotion efforts. The following year, at a press conference prior to the 1963 U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, Iacocca unveiled a concept car called Mustang II. It was essentially a doctored-up, pre-production prototype of the four-seater slated for a spring 1964 introduction. The two-seater from 1962 was renamed Mustang I.

Engineers and designers who had worked on Mustang I played hide-and-seek with the car for years to protect it from the crusher. Ford eventually restored it, and it remains on display in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, a symbol of a new era at Ford.