Through a lifetime of working on cars, Dan Walters still has the itch - Hagerty Media

For most people, cars exist merely as a means of conveyance, something to be given no more mind than, say, a dishwasher until it breaks. For the enlightened however, automobiles are a hobby, even a passion. A fortunate few, like Dan Walters, turn their lifelong love into their livelihood.

His love affair started in 1950. Walters was just eight years old when his father brought him to the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. The hook was set. He bought his first car, a 1931 Ford Model A, for $110 at 13, having spent four weeks delivering newspapers to earn the money.

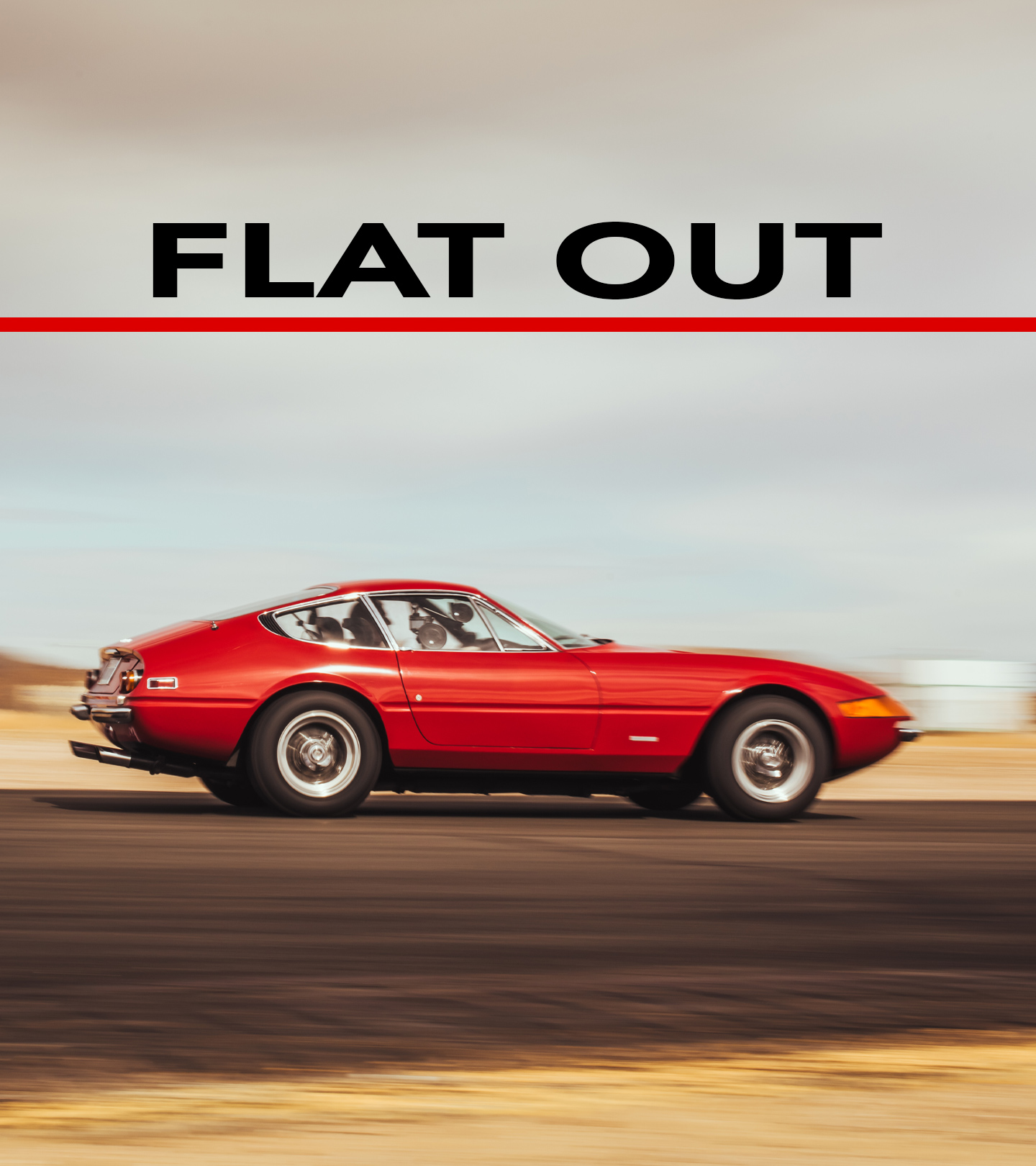

“A driver’s license, when I got one in the mid-1950s, was a rite of passage. An escape,” says Walters, sitting in an armchair in his living room in Ann Arbor, Michigan. “When my friends were all 18–25, we raced one another on the streets, and drag strips, too. Then I discovered [SCCA] road racing, where you could really drive like a lunatic. Although the state deemed it fit to take my license a number of times, I just made my own rules.”

He knew early on he’d earn his living in the car business. Over the years he worked at a gas station, a garage, and a Ford dealership and its attached collision shop, before owning his own body shop in Ann Arbor. Along the way Walters earned a solid reputation as a road racer, shade tree mechanic, and amateur restorer.

“Cars have been good to me. My income has been commensurate with the brainiacs in school, and I don’t feel frustrated that I wasn’t one of them, even though many became my friends. I have no formal training, and the phrase ‘self-taught’ sounds awfully pretentious, but I guess that’s what I am. I know how to fix things, how to do lots of stuff with cars. I learned it by reading a lot of books.”

At 76, Walters has long since quit spending his days working. But he doesn’t like the word “retired.” He keeps busy doing things like restoring a 1906 Ford Model N for the enthusiasts at the Early Ford Registry. Well-worn tools and archaic machines fill his garage, which is littered here and there with metal shavings cast off by his lathes and anvils.

Past the garage, Walters shepherds us to a building he calls the museum. As he pulls the door open and flicks on the lights, the name makes sense. Automotive ephemera, from vintage posters and signs to a plaque from his road racing days, line the walls. Just inside the door sits a row of historic motorcycles, including vintage Harley-Davidsons and Indians that wouldn’t look out of place in a real museum.

“I like bikes because they don’t take up much space,” Walters says. “Every nut and bolt is visible, which means you can access everything, but if you’re restoring it there’s nowhere to hide. And when you ride a bike like that, it makes the juices flow. Get going fast and you just feel cool. As long as you survive—they’re dangerous, of course.”

Classic cars fill the rest of the space. A Lincoln Continental from the ‘40s. A 1963 Ford Falcon. A 1906 REO, and a Ford Model A. Walters loves old cars, especially pre-war ones, because tinkering on them and driving them requires a kind of focus that tells you not only what the car is doing, but what it will do. “Sounds corny,” he says, “but that’s what lets you become one with the machine.”

Walters is especially fond of his 1950 Mercury Coupe, a car he loves for its timeless style. He remembers flying to Minnesota to buy the car in 1974, back when a ‘50 Mercury was another used car. “I drove it right home to Michigan—totally uneventful,” he says. “Even now, for a 70-year-old car, it’s very comfortable and doesn’t surprise me. I don’t drive it much around the city because of the non-power steering and need to shift constantly, but for longer drives I enjoy it. These flathead Ford V-8s are kind of fun. Pretty tough. Once you’re past their handful of idiosyncrasies, the engines are very reliable.”

Walters has owned a handful of ‘50s Mercurys, but this one’s a keeper. It’s been with him this long, he figures, and he sees no reason to change now. He’s happy with where he is and what he’s got. That’s not to say he won’t try something new. Just the other day, he got to talking with a flight instructor at the airport where he buys aviation gas. The conversation got him thinking that maybe he’d get his pilot’s license. Even at 76, his passion for anything with an engine burns brightly.