The Queen of the Hurricanes drove a Model A Roadster

At the Canadian Museum of flight in Langley B.C., docents donned gloves to push a gorgeous Ohio-built, red and cream 1937 Waco AQC-6 out of the hangar, parking it next to a fawn-colored Ford Roadster. The Roadster, a 1931 Deluxe model owned by Ed and Susan Beye, who have driven it out on this overcast day to pay tribute to a legendary pioneer in Canadian aviation. Her name was Elsie MacGill, and she was the world’s first female aeronautical engineer. She was a woman of many firsts.

The aircraft is American but it is a contemporary of the Roadster, purchased by the Canadian National Department of Defense in 1937 and, later, spending its life flying on the West Coast of Canada, where MacGill had grown up. In the fall of 1938, with the prospect of war looming in Europe, this Waco would have been ferrying Canadian military brass to important meetings, and Elsie MacGill would have been carefully easing herself into her Ford Model A Roadster, setting her canes on the seat beside her.

The canes were a necessity, as MacGill wore leg braces as the result of polio in her youth. They did not slow her down. Nothing did. She would lift her left leg and place it on the clutch pedal, select first gear, ease off the clutch with some effort. Her little Roadster would pick up speed, and on she would cruise with the urgency of an earthbound test pilot, the wind in her hair.

The traffic cops in her area knew her all too well, but they let her alone. At just thirty-three years of age, she had become Chief Engineer at the Can Car plant in Fort Williams, Ontario—another first.. In just a few short years, she would become a household name as the Queen of the Hurricanes.

Born in Vancouver in 1905, Elsie was the child of Helen MacGill, who had spent her youth as a freelance journalist covering the rapid changes in a newly-industrial Japan. Helen was also the first woman in the British Empire to obtain a university degree in music, and would eventually go on to become the first female judge in British Columbia. She was very active in the push for women’s rights in B.C., and in 1917, when Elsie was twelve, women were finally allowed the right to vote.

Elsie benefited from this strong female role model and experienced a rigorous education, with both parents deeply believing that scholarship was an important pursuit for any young person. She had a knack for taking things apart and putting them back together again, being particularly fascinated by a neighbor’s radio set. It wasn’t all engineering, though—she even received after-school art lessons from Emily Carr, who would later become one of Canada’s leading artists.

Elsie enrolled in Electrical Engineering at the University of Toronto, which for a woman was extremely unusual at the time. McGill University and Queen’s University didn’t even allow any women into their engineering programs until well into the 1940s. Elsie’s presence in classes confounded a few of her teachers, one of whom broke out in blushes and stammers after suddenly discovering he’d been expounding on flat bastard files and male and female fittings in front of a young woman. MacGill laughed it off. She graduated in 1927 and found work as a junior engineer across the border, in Michigan.

At around the same time, Ford introduced the Model A, the followup to the world-changing Model T. Ford’s T had put America on wheels, but the Model A refined that mobility with a 40-hp engine, improved fuel economy, and a top speed of 65 mph. It was a smash success for the company, with two million sold by July of 1929.

1929 was, to put it mildly, a bad year for most everyone. The Great Depression took hold following the crash of the stock market, but Elsie MacGill had a whole different set of challenges to face. She had been studying aeronautics at the University of Michigan, even winning a scholarship. She would graduate with a Masters degree in her field, becoming the world’s first female aircraft engineer, but not before she fell seriously ill. The diagnosis didn’t come immediately, and by the time it did the damage was done. That diagnosis was polio, and doctors told Elsie she would likely never walk again. Physiotherapy in the early 1930s was hardly an advanced field, but through three long years of laborious recovery, she kept up her studies, and by 1933 she was enrolled in a doctorate program in aeronautics, at MIT. Daily, she struggled up the steep staircase to the main university building on her canes and leg braces. Yet she still climbed.

It’s not known when Elsie MacGill got her Model A, nor what year it was, only that it was definitely a Roadster model. Part of the appeal of the Model A is that it was the first mass-produced Ford to have conventional arrangement of clutch, brake, and throttle pedals. Driving a Model T is good fun, but it does take the coordination of an orchestra conductor to shift gears and fiddle with the ignition advance and throttle levers. The Model A is easier to drive, and with an electric starter, makes for a dependable steed.

MacGill had a deep and long-lasting interest in civil aviation, but her career path took a different turn because of WWII. In 1938, having refused several job offers, she arrived at Canadian Car and Foundry (Can Car) as the company’s chief aeronautical engineer. Among her first tasks was the design and construction of the Maple Leaf II training aircraft, a biplane. Not only did she effectively rework an existing design with innumerable improvements, but she was also utterly fearless, undertaking test flights alongside the test pilots. If she’d had the full use of her legs, there’s little doubt but that she would have earned her own pilot’s license.

The Maple Leaf II was the world’s first aircraft designed and built by a woman. However, Elsie MacGill’s next task was the one that would bring her fame, and it’s perhaps even more impressive. She was tasked with retooling the Can Car factory to mass-produce the Hawker Hurricane, a fighter aircraft badly needed as RCAF pilots joined their British comrades dogfighting Messerschmitts in the Battle of Britain.

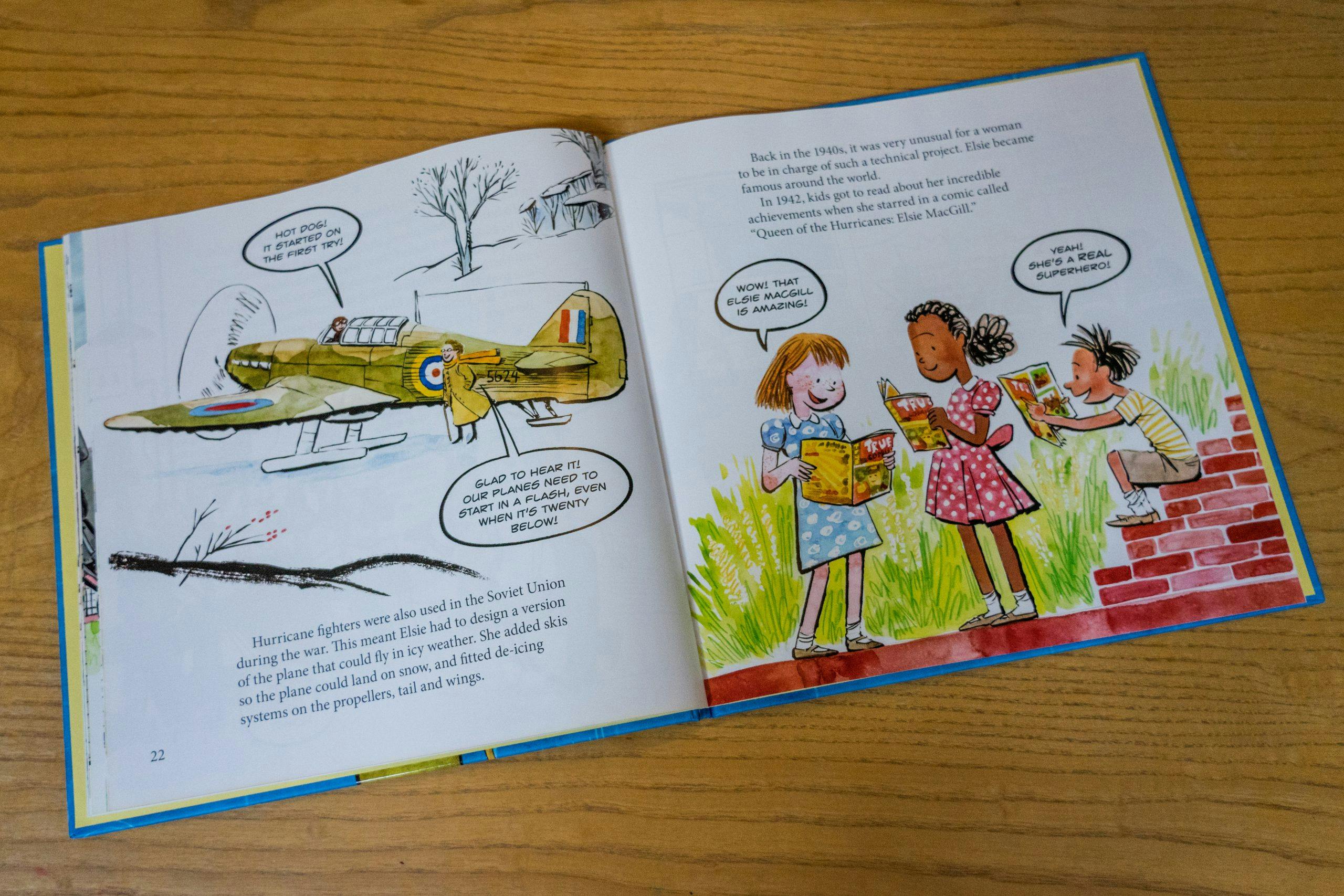

As usual, Elsie did more than was expected of her. Along with reworking the factory at impressive speed—Can Car would produce some 10 percent of all Hawker Hurricanes ever made—she made improvements to the aircraft. Most notably, she was responsible for coming up with a winterized version, complete with skis. This was the first winterized high-speed attack aircraft, and many of them were used on the Eastern front as the Russians fought the Nazis. She was not particularly happy with the fame her story brought, but the press dubbed her the Queen of the Hurricanes, and the name stuck.

Many of her fellow engineers recount carpooling with Elsie all through the cold Ontario winters, slightly alarmed by the speed of her driving and her manner of shifting gears. She often had new ideas to expound upon and was eager to get to grips with her slide rule at the office.

After the war, she continued work as both a sought-after consultant and as a champion for women’s equality. She did not like being called a female engineer, insisting that she was simply an engineer, no more, no less. She was certainly a keen mind, even cautioning the Canadian government on the Avro Arrow program. MacGill correctly predicted that investing so much on a fighter aircraft, to the neglect of civil projects, was too many eggs in one basket. The eventual cancellation of of the Arrow badly hurt Canadian aviation.

Aviation was her passion, but she was not merely a trailblazer in her own field. Through the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, she took a leadership role in advancing opportunities for women and was a strong advocate for women in other engineering and scientific fields. For her work, she was awarded the Order of Canada in 1971.

She was a woman of firsts, but that was not her initial intent. MacGill’s role as a pioneer came as a result of her ambition to achieve her goals. She simply refused to be held back by the expectations or limitations of her time. She could not, would not be stopped, not by polio, not by conventional thinking about women’s roles in society, not by the challenges of tooling an entire factory up to fight the Luftwaffe.

Elsie MacGill died in 1980, at the age of seventy-five. She was posthumously inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 1983. Her astonishing life proves that, with enough determination, the sky is the limit.