Remembering Phil Reilly, titan of the race car restoration world

I never had a brief conversation with Phil Reilly. Not because he liked to hear himself talk but because he had so much to say, and he said so much worth listening to.

Reilly, who died unexpectedly late last year at his home in Northern California at the age of 79, was a titan in the restoration world. In the 1970s and ’80s, he was a foundational figure in the creation of a market for collectible race cars, and over the past four decades, his eponymous shop restored dozens of significant cars, from prewar Hispano-Suizas and Alfa Romeos to V-12 Ferrari thoroughbreds and enough Formula 1 cars to fill several grids.

For years, Cosworth DFV motors built by Reilly were regarded as the gold standard in the collector-car universe, and dozens of them raced in Historic Grand Prix, the organization he co-founded to bring F1 cars of the 3.0-liter, normally aspirated era to the masses. He also profoundly influenced the hobby in less visible ways by hiring and then mentoring craftsmen who would go on to open shops of their own and spread the Gospel According to Phil Reilly.

“I probably wouldn’t have graduated from high school if it wasn’t for Phil,” says Forrest Teran, who now builds DFVs (and other race engines) at Teran Motor Sports. “He pretty much forced me to go to school every day. When I graduated, he made me a full-time employee of the company. Part of the deal was that I had to take college classes, but he paid for it—tuition, books, everything. And I wasn’t the only one. There are tons of characters who he would kind of take in as wayward animals and bring back around.”

For Reilly, motorsports was both his profession and his passion. He owned a huge and ever-expanding library of books that he’d not only read but seemingly committed to memory. He used to regale me with finely detailed histories of individual chassis—who’d built them, who’d bought them, who’d raced them, where they’d finished, what happened to them afterward. “He loved racing, and the history of racing more than anybody I ever met,” says Tim Coffeen, a longtime chief mechanic at Newman/Haas Racing.

Reilly’s personal car collection included a 1974 Formula 1 Brabham BT44 designed by Gordon Murray and a 1960 Kurtis/Epperly laydown Offy roadster, the Bowes Seal Fast Special. He exercised both of them regularly at the Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion at Laguna Seca Raceway and the Millers at Milwaukee meet at the Milwaukee Mile. Not so he could play hero driver but to share them with other race fans. “There were years when ten people drove the Bowes,” Coffeen says. “And I know that because I ran the starter.”

Of course, there are other accomplished mechanics. There are other successful entrepreneurs. There are other ardent and knowledgeable fans. What made Reilly so beloved among such a large and far-flung group of admirers was that he was a mensch—honest, dependable, compassionate, charitable and so ethical that he often agreed to fix problems with cars that weren’t his shop’s fault. “He was such a fine ambassador for the sport because he was such a gentleman and he lived such an honorable life,” says his lifelong friend, James King. “I have to say that I feel at sea without Phil on the planet.”

[Reilly] was such a fine ambassador for the sport because he was such a gentleman and he lived such an honorable life. — James King

Born in the Bay Area in 1943, Reilly was the son of professional ballroom dancers, but his life’s path was set when an uncle took him to a USAC Champ Car show on the one-mile dirt oval at Sacramento. After the race, driver Jud Larson lifted the young, euphoric Reilly into the hot, oily cockpit and asked him, “You want to go racing?” Reilly never looked back.

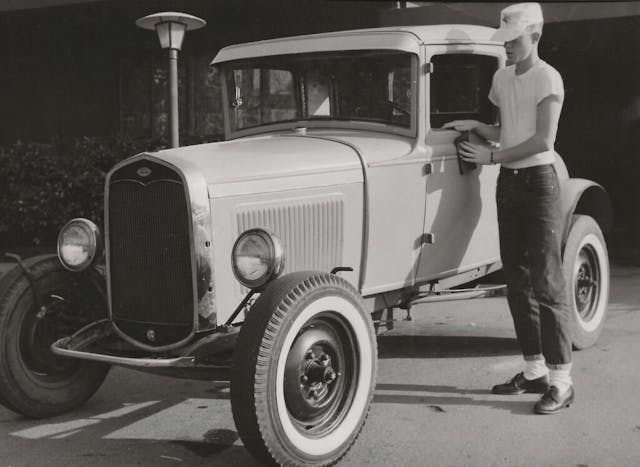

When he was 8 years old, he started subscribing to the Indianapolis Star during the month of May so he could keep track of the lead-up to the Indianapolis 500. To this day, his office walls are lined with driver autographs that he got as a kid. During high school, he drove a flathead Ford and cleaned out stables for a club racer who’d commissioned a car from road-racing pioneer Joe Huffaker. Later, Reilly began club racing himself. While prepping his Elva, he once spaced out and missed a date with his future wife, Kathy. “The car stuff just dominated his attention,” she says. “He’d get so involved that he would lose track of time.”

Reilly earned a degree in journalism, of all things. Although he was an ROTC student in college, he objected to the war in Vietnam, so he declined his commission. Instead, he was drafted and spent two years as the editor of the base newspaper at Webb Air Force Base in Big Spring, Texas. After completing his military service, he returned home and—after Leon Mandel rejected his application for a position at Competition Press—got a job with Joe Huffaker.

Huffaker was one of the most influential figures in the burgeoning road-racing subculture of Northern California. Backed by import-car dealer Kjell Kvale, Huffaker had designed and built the MG Liquid Suspension Specials, which raced at Indy, and the Genies, which were among the first American mid-engine sports racers. But by the end of the ’60s, he’d had been reduced to a tiny shop modifying what Reilly’s longtime business partner Ivan Zaremba refers to as “wind-up cars”—puny BMC sports cars—with a single employee. When that employee quit to sail to Tahiti, Reilly replaced him.

Reilly worked on Huffaker’s MG road-racing cars and built engines for a formula-car program he ran with Zaremba and local racer John Woodner. The car eventually ended up being raced by Zaremba’s friend, Stephen Griswold. Griswold was a local Alfa Romeo dealer whose father, Frank, was a Main Line Philadelphia aristocrat who’d won the first SCCA race ever run, at Watkins Glen in 1948. In the winter of 1973, the younger Griswold opened a shop devoted to restoring vintage race cars, and he hired Zaremba and Reilly to join him.

Although vintage-car racing was already a thing in the United Kingdom, it was barely a blip on the radar here in the States. Since there were so few opportunities to run them, obsolete race cars were treated like junk, and priced accordingly. Then, in 1974, Steve Earle inaugurated the Monterey Historic Automobile Races. With the existence of a prestigious venue for vintage racing, interest in historic race cars exploded. “We were there at the ground floor of resurrecting cars that had not been allowed to go to scrap,” Zaremba says. “In fact, for the first few years of the Monterey Historics, we at Griswold’s did all the tech inspection on all the cars.”

Griswold was perfectly positioned to profit from the emergence of race cars as collectible artifacts. He had the right pedigree, he had the right people, and he himself was a talented mechanic and a scholar of racing history. His shop became a go-to resource for would-be vintage racers. At one point, he was working on no fewer than eight Birdcage Maseratis simultaneously.

Even as he was managing Griswold’s shop and immersing himself in the vintage-car world, Reilly remained involved in “real” racing as part of an informal NorCal mafia campaigning Formula Atlantics. Reilly was turning wrenches in Westwood, Canada, when the cars driven by his friends Dan Marvin and Jon Norman broke during practice and were loaded on the trailer before race day. “You guys are just a bunch of punks,” somebody dismissively told them. Reilly, who had an impish sense of humor, painted their tow vehicle with “Punk Racing Team” signage and printed up matching T-shirts.

We didn’t expect to get rich. We were doing this to provide ourselves with jobs on our own terms. We were able to say, ‘I never had to do a job I didn’t want to do. I didn’t have to work for somebody I didn’t want to work for. And I didn’t have to work with somebody I didn’t want to work with. — Ivan Zaremba, Reilly’s longtime business partner

In 1980, Reilly and Zaremba teamed up with another Griswold employee, Ross Cummings, to start Phil Reilly & Company. (The name notwithstanding, the three men were equal partners.) The three of them formed an ideal triumvirate. Cummings was the virtuoso machinist and Zaremba was the old-car guru. Reilly built engines and ran the show.

“Our business approach was to treat customers as friends and welcome them into the family, so to speak,” Zaremba says. “We also agreed to a few things at the onset. One of them was that we didn’t expect to get rich. We were doing this to provide ourselves with jobs on our own terms. We were able to say, ‘I never had to do a job I didn’t want to do. I didn’t have to work for somebody I didn’t want to work for. And I didn’t have to work with somebody I didn’t want to work with.’ How many people can say that?”

After a brief stint working out of Reilly’s home garage, the company moved into a building in Corte Madera, 10 miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge. Eventually, the firm employed about a dozen artisans and earned a reputation for building cars that ran well, rarely broke and were period-correct—solid, honest, and dependable, much like Reilly himself.

Customers began flocking to Corte Madera. Because the shop didn’t specialize in any particular marque, it got a little bit of everything. The number and quality of the cars that resided there on a daily basis were so impressive that the place seemed more like a living museum than a grungy workshop. “It was the coolest place to visit,” says major-league collector Chris MacAllister. “It was like going to the Vatican.”

By the late 1980s, Reilly had earned a reputation as America’s foremost Cosworth DFV-whisperer. This wasn’t the result of a business decision. It was the product of an obsession born when he attended the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen in 1974. There, he fell in love with the trapezoidal, short-wheelbase Brabham BT44 F1 car designed by Gordon Murray.

In 1985, Reilly saw a BT44 advertised in Autosport, and he called the seller. “What do we have to do to get you in this car?” the owner asked him. Reilly bought it for $15,000, paid in six monthly installments. Restoring the car required Kathy to spend hours on her back underneath the tub, bucking rivets for her exacting (and often exasperated) husband. “It was not the best time for our marriage,” she half-jokes. Today, behind the seat of the car, affixed to the tub, is a plaque: “Kathy Reilly Racing.”

The car was restored so faithfully that, when Gordon Murray built a replica BT44 of his own, he called Reilly to ask for set-up advice. “You understand the irony of this situation, don’t you?” Reilly told him.

The Brabham came without an engine, so Reilly acquired a Cosworth DFV—the remarkable 3.0-liter V-8 that powered the vast majority of cars that raced in Formula 1 from 1967 to 1983. By taking apart and putting back together dozens of motors, Reilly solved the mysteries and mastered the nuances of the Cosworth. In later years, some would-be cheaters fitted their F1 cars with the sports car version of the engine, which had been punched out to 3.3 liters. “Phil could hear it go by once and say, ‘Nope. That’s a three-three,’” King says.

Reilly, King, and Rebecca Hale (now Evans, who ran the front office of the restoration shop), were the three major players behind the creation and operation of Historic Grand Prix. For more than a decade, HGP put together full grids of normally aspirated F1 cars celebrating the 3.0-liter era, many of them featuring engines that Reilly himself had built. The cars were authentic, the racing was hard but gentlemanly and the paddock was open to all.

Reilly drove the BT44 himself until he clipped a curb while flat in fifth gear in the Esses at Watkins Glen and spun lightly into a guardrail. Later, King and Hale asked him what happened. “The engine didn’t sound quite right,” he told them, “and I just kind of momentarily lost concentration because I was listening so hard.” Reilly chose not to race again. But he continued to put his friends in his car, and he was thrilled when Marvin finished fourth at the Rolex Monterey Motorsport Reunion last year even though the Brabham was the oldest car in the field.

Much as Reilly adored the BT44, and even though he was renowned professionally for his work with DFVs, his personal passion was the front-engine cars built for American circle-track racing, from prewar Millers to the Offy-powered roadsters and dirt cars of the 1950s and ’60s. He made an annual pilgrimage in May to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, not for the 500 but to pore over the photos in the archives, browse through the museum (where he was treated like a visiting dignitary) and bench-race with the old-timers who’d been his heroes.

Phil’s walking through the shop with his coffee, and he pivots and looks at me with complete incredulousness. He shakes his head, and he sets down his coffee, and he grabs the broom out of my hands, and he starts sweeping. ‘It’s called a push broom for a reason. This is how you use it.’ And he hands it back to me. It was awesome. I had no idea what I was doing. Without him, I’d be nowhere.” — Trevor Green-Smith, performance engineer, MoneyGram Haas F1 Team

Restoring the Bowes Seal Fast Special and other cars of that era allowed him to befriend and learn from the great craftsmen he grew up idolizing. Reilly, who looked and sounded like a professor, was committed to passing this knowledge forward. Not in a classroom but from his workbench, where he convened what Evans calls “The University of Phil.”

The curriculum ranged from cleaning and assembling a DFV to best business practices to everyday ethics. For those eager to learn, he was a willing mentor. Trevor Green-Smith, who credits Reilly with nurturing a career that’s taken him to a job as a performance engineer on the Haas Formula 1 team, remembers his first day as the sweep-up kid in Corte Madera.

“Phil’s walking through the shop with his coffee, and he pivots and looks at me with complete incredulousness,” Green-Smith says. “He shakes his head, and he sets down his coffee, and he grabs the broom out of my hands, and he starts sweeping. ‘It’s called a push broom for a reason. This is how you use it.’ And he hands it back to me. It was awesome. I had no idea what I was doing. Without him, I’d be nowhere.”

In 2015, Reilly, Zaremba, and Cummings sold their company to employee Brian Madden, who continues to use the Phil Reilly & Company name. Reilly stayed on for three years and then opened up his own one-man shop in San Rafael to do soup-to-nuts restorations at a reduced pace. “I think he enjoyed that as much as anything he’d ever done,” Norman says. “He could pick and choose what he wanted to do and who he wanted to do it for.”

In 2018, Reilly started out with a McLaren M19 F1 car, then shifted gears to work on a 1960 Edmunds/Kuzma dirt Champ car for Gary Schroeder. I last saw Reilly two weeks before he died while he was visiting Schroeder’s shop in Burbank to do what he laughingly called a “warranty job” because the car refused to go into gear. Reilly spent about 15 minutes painstakingly showing me what had turned out to be the problem: One of the screw heads on the flywheel was 20-thousands too thick, so it rubbed just enough on the clutch to prevent it from releasing.

The next day, Reilly hustled home to resume work on the 1966 Eagle Indy car that he’d been restoring for MacAllister. “He and I had been texting every day about Indy roadsters,” MacAllister says. “The next day, I got a text from his wife with the bad news. Yesterday, he was fine, and then today, he’s dead. So it was awful sudden.”

There was, and still is, a sense of shock in the vintage racing community. “I’m still reeling,” Marvin says. “This just wasn’t supposed to happen. Like somebody said, Phil had a lot of laps left in him. Boy, his loss is going to leave a big void in a lot of people’s life. Phil was the genuine article. When he said something, it was the straight deal. I don’t know what to say about his strengths because I don’t want to use too many superlatives, but I can’t think of very many weaknesses. How about this: In my book, he was 100 percent.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Hard to replace folks like this.

For 25 years Phil and his team took care of my OSCA MT4. It was the first car Griswold restored in 1973 and a year later Phil and Ivan cared for it as it was raced in the first of many Monterey Historics. Phil always made me feel welcome when I visited the shop and if there was ever a Reilly family I felt part of it. A true legend, gone way too soon, he will be missed