Paddy Hopkirk: Dancing, swinging and swaying—in the car and in life

“It was difficult with the snow and ice; the fight you had against nature.” Paddy Hopkirk, who died last week, was one of the last of the lyrical rally drivers; “One of the old school,” as a friend said, when he heard the news.

With raw talent, charm and meticulous self-promotion, the big Belfast-born wheelman built a career on slipping and sliding his way to a win in the 1964 Monte Carlo rally in his works Mini Cooper S 33EJB, with co-driver Henry Liddon alongside. It made the Mini and it made Hopkirk.

“It wasn’t the toughest rally,” Hopkirk recalled, “but it was the most glamorous. There’d be lots of journalists sitting on their arses in Monte Carlo just waiting for something to happen; sneeze and you’d be on the front page.”

Hopkirk once drove me round a precipitous hill route in a replica of that Mini, sliding the tail around, his feet a blur on the pedals.

“You use the skids to turn through the corners,” he said and on the right tires a decent driver can throw those old Minis around like a school bag full of text books, but that won’t win you an international rally against the sort of top-class opposition which faced Hopkirk and Liddon from their Monte start at Minsk in Russia. For while his driving might have looked wayward in those old BMC and Pathe News film strips, his judgement was precise down to the last inch and sometimes a lot less than that. “A dash of the Irish,” as an old Castrol promotional film put it, though it was more like a champion snooker player thinking three balls ahead, as Hopkirk’s innate car control meant he was actually setting the car up for the next-but-one corner, maybe even the one after that.

So, there was method in the madness, which given Hopkirk’s wide-eyed demeanor and enchanting manners, could disarm a few. While you were getting the round in, he’d be simultaneously several minutes into a superbly funny story and reading the room to work out who’d be able to drive him home. Rally driving in the Sixties and early Seventies could be quite a party and Hopkirk along with team members Timo Makinen and others were the genial hosts.

“He could certainly be quite a handful,” said one of his PR minders. I once inadvertently caught up with him and an adoring entourage at the end of press day at the Frankfurt Motor Show. Hopkirk was telling pure-gold rallying stories, if only I could remember any of them. There was a whisky bottle on the bar …

“You need to go home now!” said the obstreperous cleaner, brandishing a high-tech German mop.

“Well, you can try and get him out, but I think he’s made friends with the barman,” said his minder.

You can read elsewhere about Hopkirk’s extraordinary talent, but it’s the little things that come to mind. His extraordinary memory for names and faces, his million-candlepower charm and that cheeky glint in the eye; a night out with Paddy would be epic or nothing. There was that awful Harding invalid carriage, bequeathed by a local priest, in which he learned to drive. The Russian caviar, traded for silk stockings in Minsk at the start of the ’64 Monte, which Hopkirk had hidden in the Mini’s toolbox hoping to sell it in France when they finished the rally. You always got the feeling with Paddy that there was something else going on.

Less well known was his place in the works-backed ’64 Cooper Car Company Mini circuit racers (he could do it on Tarmac, too) and what about his almost mythical second place in the 1967 Italian Rally of the Flowers, where Hopkirk, leading on the final stage, broke a driveshaft on his Mini. Pushed along by the team’s Austin Princess barge, with Hopkirk gamely revving the engine and pretending to change gear, the stricken car was surreptitiously shoved right to the final control; Hopkirk even managed to drift the coasting Mini into the San Remo finish netting second place for his efforts. His swan song for the works team was another second place in the 1970 Scottish Rally in a hastily rebuilt car, which weeks before had expired on the Daily Express World Cup Rally.

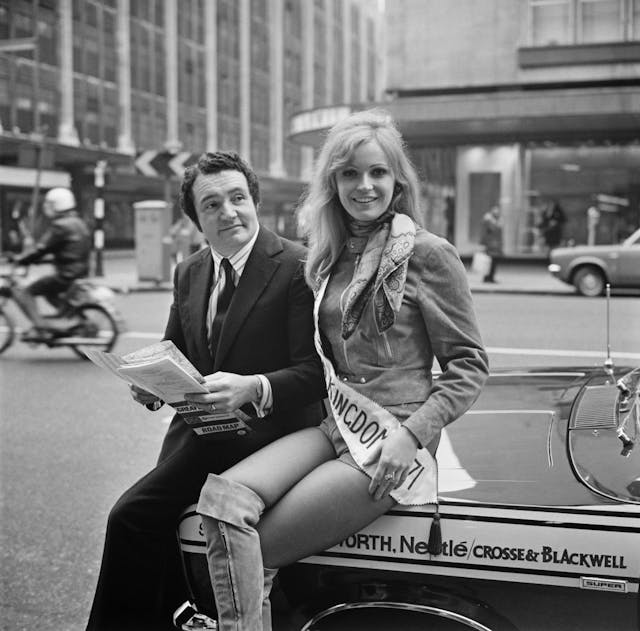

But he was “canny” right from the off, quickly realizing that rallying might have given him a name, but letters from The Beatles, and appearances at the London Palladium wouldn’t pay the bills. He built a second career on simply being Paddy Hopkirk and by 1966 you could kit your Mini out with Paddy-Hopkirk-branded padded seat covers (De Luxe version £8 19s 6d), a “Safety Wheel,” sump guard, spot lamps, fly-off handbrake and finish it off with Paddy Hopkirk fireproof overalls in white with red striping at £8 15s.

“Paddy Hopkirk doesn’t need to show off’, read the advertising copy in a 1970 Lucas spot lamp ad, as the big man leant against the wing of a Mini.

He always said that winning the Monte ‘was the making of me’; he bought a house in London on the strength of it (“It was in Belgravia, 40 Groom Place; Jimmy Clark rented a room with me for a while”), but Hopkirk’s enduring fame was all his own well-deserved work. For he was a genuinely nice guy, interested in other people, generous with his time and attention and far from the media-trained, branded-to the-max self-obsessed stars of today. Small wonder BMW, seeking to promote the new MINI, recruited Hopkirk and John Cooper as subtle links with a glorious past. Nor was Hopkirk too proud to admit his weaknesses and he was fulsome in his praise of his mechanics, team managers such as Stuart Turner and the role of pace notes, endless practizing and ice notes in his success.

That he could drive there was little doubting, but it’s the way he drove that left you speechless. Few will remember the Morris Cooper S, but it’s worth remembering just how little power it had. It might have weighed just 660 kg, but with twin SU carbs, the 1071-cc engine mustered just 70 bhp and 62 lb-ft, enough to give a top speed of 94mph and a 0-60 mph time of 12.9 sec—all for £695 7s 1d, or about £10,325 in today’s values. While hardened testers at The Motor magazine called it “a full-grown wolf”, it was hardly sporting in today’s terms.

To get the best you had to dance the little car, swinging and swaying like the back beat of Hippy Hippy Shake by the Swinging Blue Jeans, which was in the charts in January 1964. And that’s how Hopkirk drove, managing that tiny lamp of an engine and the scant grip from tiny Dunlops, tripping the light fantastic right into the history books.

The afterlife has just got a lot more fast and fun …