Lancias Are the Treasures at the Heart of the Spadaro Family

Dominick European Car Repair has been an automotive fixture in White Plains, New York, since 1961. I’ve always been curious about its origins, so recently I sat down with Frank, Vera, and Santo Spadaro, the three children of its indomitable founder, Domenico Spadaro.

At the age of 12, Domenico Spadaro was old enough to learn a trade. “His father believed he should become a cabinetmaker,” says Spadaro’s youngest son, Santo. “So Dad was sent to the local woodworking shop to start his apprenticeship. He spent a single day amongst the woodworkers and knew this wasn’t his destiny. He exited the building, walked to the local garage down the street, and asked the owner to teach him to be a mechanic.”

Four years later, in 1936, the 16-year-old Spadaro opened his first shop, in his grandfather’s barn. Following the war, he bought a building on the main street in Roccalumera, Sicily, and opened a proper facility. “As time went on, Dad’s reputation grew,” oldest son Frank says. “He was the go-to mechanic for anything from a diesel truck to a Vespa, an 8C Alfa to a Lancia.”

“From the very beginning, he appreciated how the Lancias were engineered and built and how they drove,” Santo says. With out-of-the-box thinking that allowed for designs and technologies that were way ahead of their time, “they were cars built for people with a mechanical eye.” Perfect for a young man like Domenico Spadaro.

In 1948, he met a girl from the next town over, Tindara Dibella. Within six months, she and her family were off to America. “We were told Dad couldn’t get this beauty who would become our mom off his mind,” Vera says. “Letters went back and forth across the ocean, and in 1953, they decided to be married.” A year later, Domenico left Sicily and his successful business to start a new life in the USA.

He started at International Motors in White Plains, where he spent six years. During this time he changed his name to Domenick in order to assimilate to his new home. The siblings all agree their father was a naturally skilled mechanic, regardless of the machinery put before him. “He was given an XK120 that never ran right, and he returned the car running as smooth as silk,” Santo says. “The customer said to him: ‘You must work on many of these.’ Dad said: ‘I’ve never seen one before.’ He just knew how machines worked.”

In 1961, Spadaro opened Dominick European Car Repair (that’s what it says on the sign). Like his shop in Sicily, the White Plains shop’s reputation grew to be the destination for European cars.

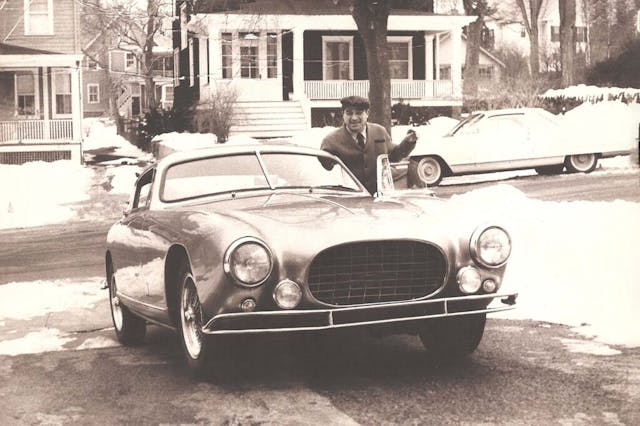

He especially had an affinity for Italian cars. His first Ferrari was a 250 Europa that had been rolled. Spadaro brought it back to life, drove it for about three years, and then moved it along. Lancias always held a special place in his heart, however. In 1964, Spadaro became a Lancia dealer, selling Fulvias, Flavias, and Flaminias. It was a short-lived endeavor, though, as Lancia abandoned the American market in 1967.

Santo recalls a family trip to Sicily in 1976. “One of our cousins told our dad about a 1966 330 GT 2+2 in a town close by. The original owner was getting on in years and was getting a bit too large to fit in the car. The Ferrari followed us home and joined the stable. That became the car for Sunday outings with the family. The three of us fit in the back (sort of), and off we would go to visit family, have a nice meal, visit Watkins Glen, or head to Florida. It became part of the family.”

The shop was Domenick’s American dream, but he was adamant that it was not the American dream for his boys. They would go to school and secure positions where they would wear pressed shirts, nice suits and ties, and not get their hands and fingernails dirty.

They could have fancy cars and understand how to work on them, but it would be for fun, not a profession.

Franks’s memories don’t jibe with his dad’s wishes, however. “I was studying mechanical engineering at college, but I was also always running errands for the shop or helping stranded customers. Dominick’s was a constant in my life. After graduation, Dad’s garage was my first job. I’ve never worked anywhere else but Dominick’s.”

Santo studied finance at Pace University, and after graduation worked as an assistant comptroller in an advertising agency for 10 years. It was interesting work, but barely. So, just like his father, he decided that this line of work was not for him and began inserting himself into the goings-on of the shop. Domenick was not pleased, but after time, lots of time, actually decades . . . he finally recognized the passion and bond his sons had for the place and the work happening there, and he discarded his vision of seeing his sons occupying corner offices in tall skyscrapers.

By that point, the shop had become well-known in the world of Lancia owners. In 1982, this brought Italian-American tenor and actor Sergio Franchi there with an intriguing project. He had a B24 Spider America in boxes and wanted a mechanical restoration. Domenick took on the task, and a year later he delivered a beautiful B24 to Franchi’s Stonington, Connecticut, compound. Franchi was a collector of American, British, and Italian cars but had limited garage space, and with the return of the Lancia he now had one car too many. Frank still remembers that delivery: “There was a particular car in the collection that caught Dad’s eye: a low mileage, well-preserved 1961 Touring-bodied Lancia Flaminia GT. Dad made a deal, and the Lancia was partial trade for the work on the B24.” They drove to Connecticut in one Lancia and returned home in another. The Spadaros now had a second Sunday driver.

For the other days of the week, the elder Spadaro wanted something a bit special. Frank had recently acquired a Fulvia 1.3s, and while his father was intrigued by the little car, he had his eye on something else. In 1983, a good friend of Domenick’s, Armand Giglio, had imported a 1600 HF for himself, and once he laid eyes on it, Domenick knew that he, too, wanted one.

“The 1.3s was like driving your living room,” Frank says. “You have big plush seats, a big steering wheel, and a long-throw gear lever. The HF is a little more of a workout. The revs come up fast, everything happens faster. You’re driving a sports car.”

“Dad contacted his cousins in Italy, “Santo says. “Within a couple of weeks, they found him a car and put it on a boat to the U.S. The only problem was that it sat on the docks for over a year, waiting to be federalized.”

That entailed adding safety glass, three-point inertia belts, an evaporative emissions system, and bumpers to a car that never had them. Part of the federalization was putting a new tag on the door jamb stating what the car was and who had imported it: The tag still reads, incorrectly, “Dominico Spadaro.”

Domenick owned the HF for about seven years, but with time he realized he was a more of cruiser than the frenetic little car was, and in 1990 he sold it.

Sometime in 1996, the Spadaros got a call from Miller Motor Cars in Greenwich, Connecticut. Miller had a Lancia head that needed a valve job, so they brought it to Dominick’s, which did the work and sent it back. Around the same time, Frank was diagnosed with cancer and was searching for an outlet—something to take his mind off the chemo and radiation. He and Santo looked at a 308 GT4 , which was not as advertised, an Alfa, and a few other cars, but nothing fit the bill. Then they stopped by Miller Motor Cars, and there was the Lancia they had done the head for—an HF.

“Werner Pfister was a good friend and the sales manager at Miller,” Santo remembers. “He told us the car had become a running joke at the shop as no one wanted, or even knew how, to put it back together. The car had undergone a cosmetic restoration, but the engine was too challenging for them.”

Frank thought they should buy it. What sealed the deal was when they opened the door and saw the tag: Imported by Dominico Spadaro. The Lancia returned to the shop with them, and the Spadaros rebuilt the engine over the winter. Now Frank had his happy place; this was the car he would keep for life.

Later that year, Domenick had a stroke. “Dad fought his way back but could no longer do everything himself,” Vera says. “This gave me the chance to help out and be closer to him.”

Though at one point she had wanted to be a race car driver, Vera had been the only Spadaro child to remain in the corporate world and had served as an associate director in Bear Stearns’ investment banking division. She’d come into the shop when they needed an extra hand but otherwise had her own career path. But once Domenick fell ill, and seeing that her father seemed to bless this new addition, she stayed on.

Domenick continued working alongside his family in the shop until a few days before he died in 2009, at age 89.

Frank beat cancer and enjoyed the little HF for a couple decades, but his relationship with the car and with driving was severely tested in 2018 when he lost his right leg below the knee.

Santo, a tinkerer in his father’s image, picked up a used prosthetic from eBay and started making some modifications. Many people have prosthetics, but the demand for one that could work with a brake or a clutch pedal was low. They added a roller and some articulation and dubbed it Mk I. Soon their friend, Steven Dibdin of Additive Restoration, got involved and took the project to a specialist in Washington, D.C., for further refinement. The Spadaros are now on Mk III. Lancia was known for its innovation, and in that spirit the brothers created an innovative leg so Frank could continue to enjoy his car.

It was never written in Domenick’s will, but it was said many times that the 330 GT would go to Frank, and it was implied that the Flaminia GT would go to Santo. Vera had no qualms with that. “My first car was a Lancia Fulvia 1.3,” she recalls. “I didn’t have it long, as Dad sold it out from under me. This happened to me a few more times. Now, I’m not much for driving old cars, so I had no argument about who would get Dad’s cars. As long as I get to ride in them.”

Santo, like his father and his brother, is a Lancisti, and his affection is deep. “I appreciate the effort that goes into beautiful design,” he says. “Not just the exterior beauty, but the work that goes into engineering and castings. Beauty is more than skin deep. It’s a bonus that the cars are beautiful; what lies beneath is equally impressive. You open the hood and marvel at the innovations.”

Once upon a time, he owned and then sold a 1954 Aurelia B20. Later there was a Fulvia he bought sight unseen for $500 from the West Coast, which was described as clean but non-running. “When the Lancia arrived at the shop, I realized all the car needed was a battery, a front spring, and an idle box. I had those parts,” Santo says. “Within a few hours of arrival, the Fulvia was on the road. It had cost more to ship the car than the purchase price.” That car now resides in the collection of automotive pundit and occasional Hagerty contributor Jamie Kitman.

In 2015, the hope of replacing the B20 started to fade as prices escalated. The next best thing was a unicorn left-hand drive Aurelia B10 with a willing V-6 and lots of Lancia style and build quality. Shortly after, there was a Fulvia hill climb and rally car Santo found on eBay, fully caged but with a blown engine. He outfitted it with a hot motor capable of running on pump gas, and with Santo at the wheel, it has entertained scores of fans at the Lime Rock Historics ever since with its three-wheeled antics going into Big Bend.

All of the Lancias that have passed through their hands have been special to the Spadaros, but their connection naturally runs deeper with two of them: “When Frank drives his HF, it’s a reminder of his time with our dad,” Santo says. And when he drives the Flaminia as his father did, on sunny weekend days through the country, “it brings a nice piece of Dad back to me. Shifting the same gears he shifted. Shifting them in the way he taught me.” The Flaminia gives Santo a visceral connection to Domenick. He is in a wonderful place behind the wheel, with his dad’s spirit riding shotgun.

You’d be hard pressed to find a nicer family or better ambassadors for older Italian cars for driving (and vintage racing). We are lucky to have these folks around.

My brother had a Lancia for a year or so in high school. I don’t know the model, but it was a convertible. Prone to overheating in the summertime, as my sister said he always had the heater on when she rode in it. Replaced it with a early to mid 70’s Corolla SR5 hatchback. The Lancia was always having issues.

This is a really beautiful family story. My Italian wife approves!

Dominick European Car Repair is a living legend, living because it is just as active today, the stories are still being written. I bring my Alfa there for service and improvements, and it is an absolute pleasure, I would even say a privilege, to have them work on my car. There are always other exceptional cars to see there. And it is truly a pleasure to engage with Santo, Frank and Vera, they are wonderful people.

Great story about a talented family. Thanks for sharing it and the photos as well.