Hot rods and surfing (still) go hand in hand

Growing up in El Segundo—one of the beach cities in L.A.’s South Bay—Tyler Hatzikian was steeped in surfing and hot rod culture. He liked talking with the old-timers who had grown up in the ’40s and ’50s and had lived through the post-Gidget surfing boom and the golden age of hot rodding. Even as a teenager, he wanted to know what they knew—how they shaped boards and built cars back then. Those have been his twin passions ever since.

As far back as anyone can remember, Southern California has been a mecca for all things recreational, with wave riding and hot rodding taking command of the most visible spots in the lineup. Surfing and hot rodding weren’t mutually exclusive, and many of the surfers who made money selling boards or winning contests put that money into the hot rods, muscle cars, and sports cars that announced their arrival at the beach.

That time had long since passed when Hatzikian graduated from high school in 1990. Boards were short, Day-Glo was in, and fast cars had become more like computers. By the time he was 18, he had already been shaping and selling boards for a few years—it would become his life’s work, after all—and restoring a succession of tri-five Chevrolets.

One hobby to fund another

“Starting in high school, every penny I made making surfboards went into restoring cars,” he said.

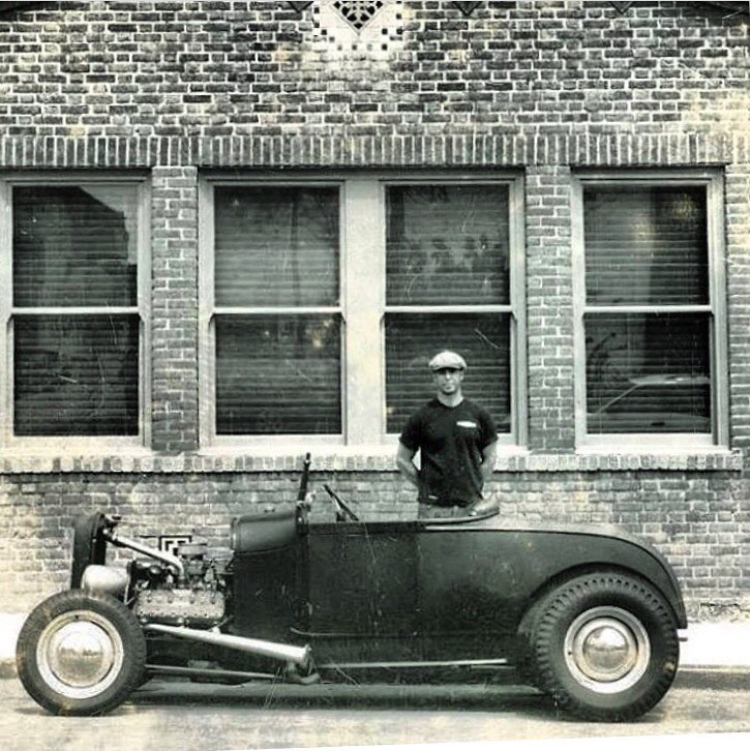

A photo from those years shows him standing proudly in front of a yellow Chevy. By the time he was in his early 20s, he had learned enough about surfboard shaping to know that his affinity for older cars was something he could translate into surfboard design.

“I said shoot, man, I build surfboards, but I know more about classic car design than I do about the history of surfing,” he said.

So he decided to focus on a period of surfing history that paralleled his interest in cars—the ’50s and ’60s, the last years longboarding had enjoyed widespread popularity. The late ’60s saw a shift toward shorter, more maneuverable boards, pushing longboarding almost instantly into obscurity. By the early ’90s, when Kelly Slater was impressing the world with his superhuman feats of raw athleticism perched atop a tiny potato chip board, Hatzikian’s idea to dust off the unwieldy longboard and make it his own was well outside the norm. But that’s what he did, eschewing rad wave slashes for an elegant style of movement that’s more akin to ballroom dancing, and building the boards to match.

To Hatzikian, the choice was natural. The old-timers had always been there to guide him. His dad rode longboards in the ’80s, long after they’d been relegated to the province of lameness by the stronger currents within surfing culture. He drank coffee and chatted with local guys who had built boards and surfed during the postwar years, and he befriended Hap Jacobs and Dale Velzy—lions of 1960s surfing and board design.

“I’d ride down to San Onofre with Hap in his El Camino to go catch some waves and we’d just talk story,” Hatzikian said. “For me, that hour-plus drive felt like 10 minutes because we’d have really great conversations.”

Hatzikian asked a lot of design questions of Jacobs during those trips, but also got a lot of little anecdotes out of him about things they’d done in the old days—the little details that add color to any generation’s story.

“I was just trying to feed my own interest—I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I gotta get this stuff before these guys pass on,'” he said. “Now, you’re stuck with what you can read and what you can find on the Internet. Those guys are all dead.”

Finding a flow of his own

So Hatzikian took what he learned, both from his experience rebuilding old cars and shaping boards and from chatting up the old masters, and developed a style evoked his interpretation of how things would have gone if time had slowed to a crawl as the longboard era drew to a close. He used tinted fiberglass resins and pinstriping reminiscent of Von Dutch designs and large, colorful graphics that would have looked natural on lakebed speedsters out on the salt at El Mirage.

But for Hatzikian, before there was surfing, there was racing. He started shaping boards when he was 12, but before that, his life goal had been to become a race car driver. The proof came from his mother, who recently gave him a third grade “what I want to be when I grow up” project that consisted of magazine cuttings pasted on paper, complete with scrawled-in narration. Page one: “I’m going to be a race car driver.” Page two: photos of sprint cars. Page three: a Rip Curl ad, along with the words, “Surfing will be my hobby.”

As it turned out, life developed in reverse of his early plans. Years later, having made a name for himself as a surfer, shaper, and all-around longboarding exemplar (including sharing film credits with the great Slater at least once), he’s gotten into racing wingless sprint cars on dirt ovals around Southern California. It’s expensive, and he’s already suffered one major, car-destroying crash, but Hatzikian approaches it the same way he did when he was learning how to shape boards and restore cars—he talks to the guys who have been doing it for a while.

“Now I’m having conversations with guys like Ed Iskenderian, Ron Shaver, and Page Jones, and all of a sudden, these classic stories come out,” Hatzikian said. “I was the kid rolling up my program and sticking it through the fence to get these race legends to sign it. Now, they’re on the other side of the fence watching me race and giving me advice. It’s amazing. It’s like surfing with Hap Jacobs.”

Hatzikian doesn’t figure he’s mastered the craft of surfboard shaping. But the rate at which he’s learning within his chosen discipline has slowed. Jumping into sprint car racing—running up the steep side of the learning curve—has given his creative juices a boost. He has a habit of identifying the seasoned artisans within one of his interests—in this case, mining the traditions that make racing what it is. That, as always, has gotten him closer to its essence. And the same way he leans on old-timers to soak up knowledge, he feeds off the inquisitive energy of people who are just getting into surfing. If you’re passionate and you’re respectful of those who came before you, he says, people generally open up and share what they know.