Groundbreaking designer McKinley Thompson’s quest put the world on wheels

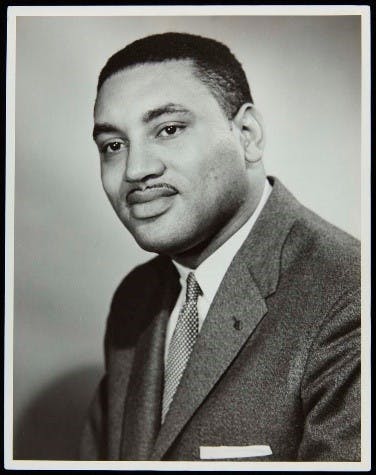

On his first day at Ford’s Advanced Studio in 1956, McKinley Thompson Jr. received some simple words of encouragement from George Walker, Vice President of Ford Design: “You can go as far as your talent will take you.”

Message received, and challenge accepted. In a sense, it was also mission accomplished for Thompson, who that day became Ford’s first Black designer.

Thompson, born November 8, 1922 in New York City, was bitten by the car bug at an early age and enjoyed sharing the story of the exact moment it happened. It was 1934, and 12-year-old Thompson was walking home from school in Queens when he saw a new silver-grey Chrysler DeSoto Airflow at a traffic signal about a half-block away. He ran to get a better look, but then the light changed, and the car was gone.

It didn’t matter. Thompson never forgot it.

“There were patchy clouds in the sky, and it just so happened that the clouds opened up for the sunshine to come through,” Thompson told The Henry Ford in 2001. “It lit that car up like a searchlight.

“I was never so impressed with anything in all my life. I knew that that’s what I wanted to do … I wanted to be an automobile designer.”

Segregation was the rule of the day, and studios at American automakers were not overflowing with Black designers. It would be another 13 years before Jackie Robinson joined baseball’s Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, historically integrating “America’s game.” Robinson’s courage, composure, and Hall of Fame career helped pave the way for others to pursue professions that were previously considered off limits.

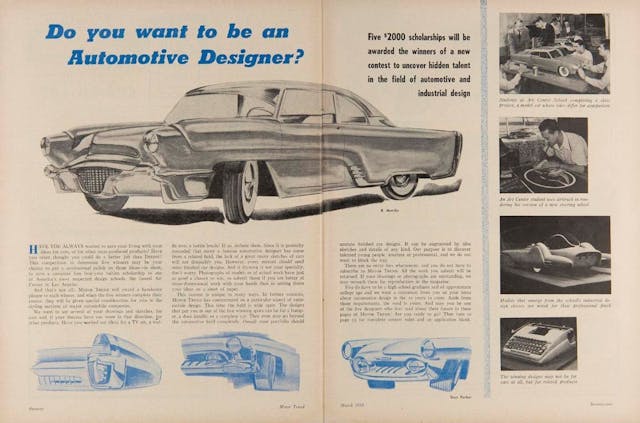

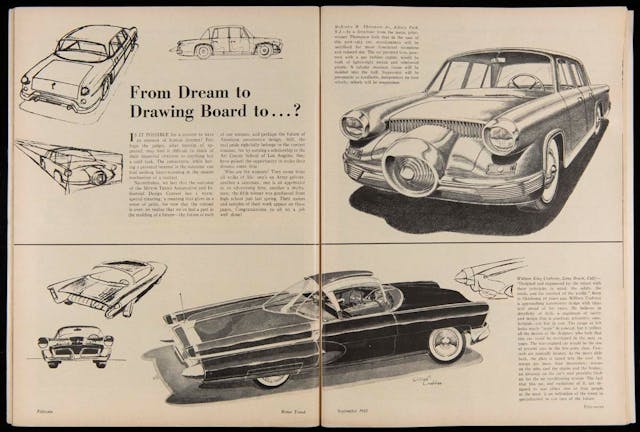

Thompson was a talented artist who excelled in drafting and commercial art in high school, which led to a job as an engineering design layout coordinator for the Army Signal Corps. He was later drafted to serve in the Army Corps of Engineers during World War II. Following the war, he returned to the Signal Corps and could have easily let his aspirations slip away. After all, by March 1953, Thompson was 30 years old, married, and had started a family. But then he saw an announcement for an automotive design contest in Motor Trend magazine, and that changed everything.

“Have you always wanted to earn your living with your ideas for cars or other mass-produced products?” Motor Trend asked. “Have you often thought you could do a better job than Detroit? … Our purpose is to discover talented young people, amateur or professional.” Thompson’s eyes must have widened. The magazine was speaking directly to him.

He entered, hoping to become one of five winners who would receive a scholarship to attend the prestigious Art Center College of Design in California. Thompson’s design, a car that he imagined would be built of reinforced, lightweight plastic and powered by a turbine engine, was not only chosen, it was prominently featured in the magazine when the winners were announced six months later.

In September 1953, Thompson became the first Black student to enroll in the school’s Transportation Design department.

Upon graduation in 1956, he interviewed for a design position with Ford and was hired immediately, breaking the color barrier at another automotive institution. Appropriately, Thompson joined Ford’s Advanced Studio, in which designers were without creative restriction and were encouraged to think outside the box.

Thompson’s early design work included a light cab-forward truck, and he also contributed sketches for the Mustang, GT40, and futuristic Gyron concept car. His early design drawings for the iconic first-generation Bronco look a lot like the SUV that eventually went into production, but he didn’t receive credit at the time.

Thompson also worked on the Thunderbird and Falcon designs.

“McKinley was a man who followed his dreams and wound up making history,” says Ford Bronco interior designer Christopher Young. “He not only broke through the color barrier in the world of automotive design, he helped create some of the most iconic consumer products ever.”

It was another car, however, that ultimately consumed him. Thompson dreamed of creating a vehicle that could change the world—parts of it anyway—a dream that began in the mid-1960s and continued well into the ’70s and beyond.

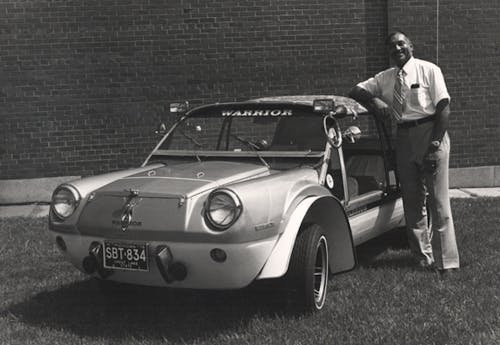

Thompson envisioned an all-terrain vehicle that he called the Warrior, which would satisfy the transportation needs in impoverished areas of the world and offer economic benefits as well. The vehicles would be easy to build and maintain, and Thompson suggested they be produced in those same developing parts of the world.

His dream didn’t stop there. Thompson hoped that the Warrior would be the first in a series of vehicles that included a half-ton pickup truck, a small bus, and amphibious cars.

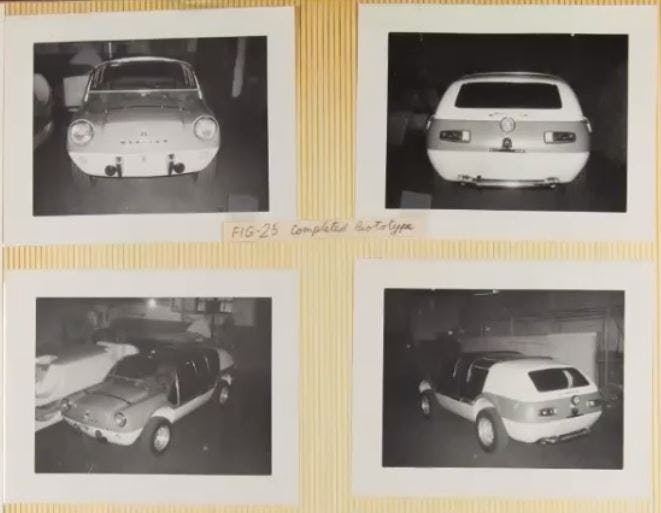

Originally designated “Project Vanguard,” the Warrior concept vehicle was constructed of Royalex, a strong space-age plastic produced by Uniroyal. It was modeled on the Renault R-10, a small four-door sedan, and powered by the R-10’s 1100-cc four-cylinder engine.

Thompson presented his idea to Ford in 1965, and although he received positive reviews from executives, they decided that the company couldn’t sell enough of the vehicles to cover the initial investment.

Undeterred, Thompson recruited friends to invest in developing the Warrior for the African market. One of those who joined the cause was Wally Triplett, who in 1949 had become the first Black person to play professional football for the Detroit Lions.

Renting a garage in Detroit, Thompson would work a full day at Ford, then spend up to six more hours on the Warrior. “My family was very good about that,” Thompson told The Henry Ford. “My wife knew how badly I wanted to do this.”

As for Triplett, he did more than contribute financially; he was also involved in the Warrior’s construction. Thompson and Triplett completed the concept car in 1969, and Thompson continued to make modifications while looking for an automaker to produce it. In addition to its off-road ability, the Warrior offered a top speed of 75–80 mph and fuel efficiency of 35–40 mpg.

Still, no one stepped forward to build it. Thompson’s partners suggested they produce it themselves, but the group was denied the loans needed to make it happen. Triplett later suggested that race had something to do with it. Thompson eventually stopped searching for investors in 1979, and he retired from Ford in 1984. Hoping to inspire young people to consider a career in automotive design, he created a traveling exhibit—with the Warrior front and center—and visited schools, mainly in the Detroit area. In addition to cruising around the Motor City, Thompson often took the Warrior on family vacations; he even off-roaded it at the Sleeping Bear Dunes in northern Michigan (until that sort of thing was banned).

In 1995, Thompson received a dose of vindication when another inexpensive all-terrain vehicle, the URI (the Khoisan Nama word for “jump”), was introduced by a goat farmer and inventor in Namibia named Ewert Smith. The URI went into production there in 2001.

That same year, Thompson donated the Warrior concept vehicle to The Henry Ford. Five years later, he passed away from complications attributed to Parkinson’s disease. He was 83.

Thompson and the Warrior were both groundbreakers, and although the concept car’s designer always regretted that he couldn’t bring it across the finish line, he was thankful for the opportunity.

“God has blessed a certain number of people in the world with talent and ability, and I’ve always felt that those people that have that blessing—creativity and imagination—owe it to the rest of the population to make life as good as it can be,” Thompson told The Henry Ford, which earlier this year hosted a Facebook Livestream to tell his story. “It was rewarding to me to know that I was trying to make that kind of an effort. I felt good about that.”