Why is the automotive repair industry in need of so much repair itself?

Nightmare stories about crooked or incapable shops aren’t anything new, but even for me, it seems increasingly tough to find reliable proprietors of some the more menu-item kind of work. Changing tires, alignments, A/C recharging—the kind of stuff that doesn’t require a hardcore diagnostic adventure to complete the service. Line work common to a technician’s skillsets. Friends increasingly reach out to me for advice on chaotic interactions with service writers more often than questions about whether the mechanical problem is this-or-that. And as much as I want to write this off as mere anecdote or a symptom of cathartic bias, it’s hard to ignore the surface cracks indicating trouble within the foundation of the automotive repair industry. Are shops under more stress and tension than they can handle?

Blaming the pandemic is the blanket answer, naturally, and is playing a role in some aspects of service quality. The troubling reality, however, is that customer satisfaction within the automotive industry was already on the decline, according to experts, and it strongly coincides with with a deep-rooted shortage of qualified labor. Notably, the rate of skilled technicians coming into the industry to replace retiring baby boomers has not been on balance for decades. My two cents? Like an artist, a tech needs to be given the best environment possible to succeed in order to meet the customer’s expectations.

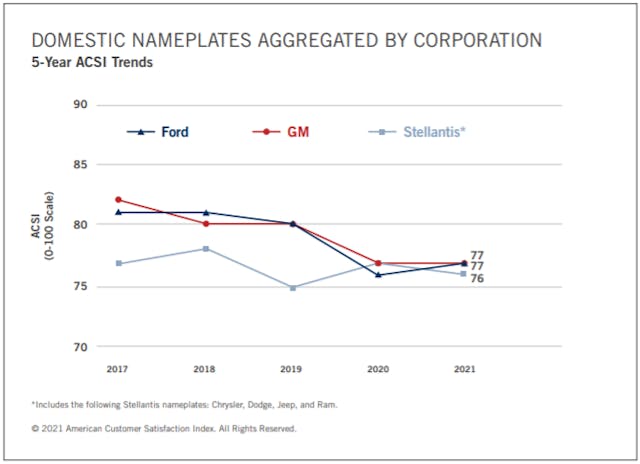

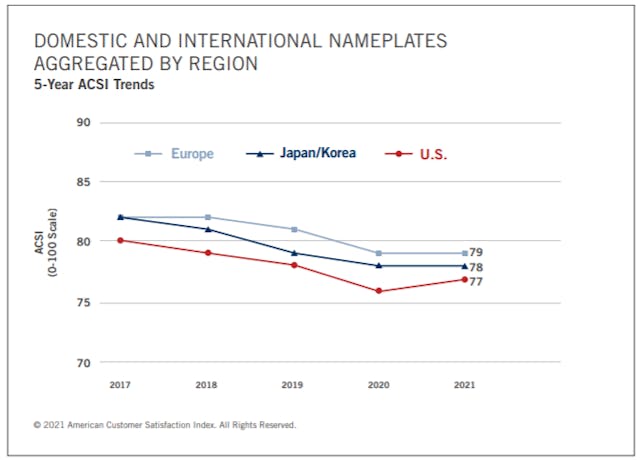

So why the decrease in satisfaction of customers and technicians alike? According to data from the American Customer Satisfaction Index, the industry as a whole has seen a decline over the past decade when it comes to keeping those walking into the lobby happy, especially regarding domestic brands. Recalls, parts shortages, extended lead and repair times—all of these negatives stack up and are compounded by systemic problems within fixed operations. The technician shortage has had the biggest ripples.

If we look at the labor pool in the automotive repair industry as just that, a reservoir, it would be one in drought, losing water quicker than it is being replenished. The simple fact of the matter here is that there are not enough new technicians entering and staying committed to the field to backfill those who are retiring and leaving the industry with decades of busted knuckles. The longstanding issue is the departure of tenured talent, and getting beyond the simple answer of age, certain factors are greasing the downward slide. A big one is the lack of benefits. Two weeks of vacation is still often reserved for techs after their first year, which discourages workers from jumping ship to better dealership or shop as they may not be able to afford giving up their accrued weeks to start over with a new employer. The healthcare situation isn’t great either, with underwhelming insurance for what remains a physically demanding job imparting significant wear and tear on a tech’s body over their career. Need to go to a doctor’s appointment some time during your first year at a new gig? One fewer vacation day, my friend.

Let’s talk about compensation. There’s a notable discrepancy in pay when compared to other roles in an independent repair or dealer setting, wherein service advisers, finance officers, and sales staff can earn higher pay rates than techs. These other roles can clear six figures in some markets (median income for technicians is around $65,000) without the rigorous training and certifications required of techs, who also have to front the cost of new tools.

On top of all this, long-tenured techs are choosing retirement over the time and training investment to service the rapidly evolving alternative powertrains in modern vehicles, such as EVs (at least in the short-term). This situation is creating an arms race for equipment and knowledge. Modern technicians are no longer just mechanics but must also harness computer and electrical engineering knowledge. Beyond that, flat-rate/flag-hour based pay is becoming less popular with today’s more complicated vehicles and, in many cases, less profitable as manufacturers revise their labor books with fewer calculated labor hours for some jobs. The OEMs are citing efficiencies in some new repair process, which results in less pay to the tech rather than further encouraging quick work through more profitable jobs for the given labor rate. Worse, too, is the fact that many factors well outside a tech’s control can affect his or her paycheck greatly: think service advisor politics, parts shortages, and tricky diagnostic adventures (which often aren’t paid based on the time spent figuring the problem out, meaning more difficult jobs can suck a tech’s pay down when it takes longer to diagnose the fault).

For those entering these shell-shocked battlefields, the above issues become apparent early in a technician’s career. Of course, that’s assuming someone is entering the field for the first time. Shop classes at the middle and high school level have been the victims of budget cuts for decades, in part due to the required resource investment. Meanwhile, the prevailing message to students from high school staff has prioritized pursuit of academic-focused four-year colleges degrees over trades. Many industries are attempting to deal with this slow take rate for trade schools by anteing up with offers of generous pay, equipment reimbursement, company-supplied tools and vehicles, and other adjustments designed to attract young talent. Yet these are moves that the automotive industry has, bizarrely, rarely adopted. It’s easy to see how such reforms would directly address the current high-turnover environment, as techs either burn out or constantly hop from one business to another, surfing just long enough for the next job offer. Folks with wisdom, experience, and keen diagnostic instincts eventually seek a landing pad with fleets in government sectors, aircraft maintenance, or sometimes an entirely different trade.

This uneven labor trade-off has driven a shortage of somewhere between 10,000 to 20,000 technicians every year, by most estimates. Concerning the shortage over the next five years, estimates ranges wildly on the body count needed: anywhere between 25,000 and 642,000. The result is a recession of reliable, quality shops as service managers scramble to bring enough workers in to meet demand, which has grown substantially during the pandemic. With the valve closing on a supply of newly trained techs, some shops are left with less-than-ideal staff, if they have any at all to hire, further entrenching the troubled state of the industry. A loss of experienced talent in the labor pool results in higher return rates for follow-up work on a job, either due to a workmanship errors or outright misdiagnosis of the issue. Without a well-trained bucket of younger workers feeding into the industry, many shops are unable to hire enough techs to keep up with demand, resulting in long turn-around times and far-out schedule slots for work.

Attempts at course correction begin at the leadership level in many cases, with a number of shops moving away from paying technicians by flag hours (as previously mentioned) and moving towards conventional salaries, some with the addition of a commission based on revenue, split by the individual or by gross shop sales. This measure removes some of the pressure of beating the clock on the book’s labor hours for a given job, a situation that normally does as much to encourage speed as it does contribute to technician burnout on trickier jobs that eventually exceed the book time, or worse, cause mistakes. Crafting a supportive shop culture is also key, whether that be in the form of providing tools, additional benefits, and training for techs. Some of this may come from reestablishing service advisors as customer service roles and less as salesmen of the service department by, for example, pressuring for upsales with a commission structure that is untangled from the success within the shop of the work they sell. It’s not hard for there to be a large discrepancy in income between the two roles in situations where service advisors can sell more work (thus generate large commissions) than the shop can reliably process.

In our education system, the modern STEM movement could easily translate into intelligent students pursuing careers as electricians, mechanics, plumbers, or just about any other trade; they all rely on a practical understanding of engineering, math, and physics. The push for college diplomas by educators as the most vital key to success has created an environment where there’s not just a shortage of workers in certain trades, but an oversaturation of college-degreed individuals in other labor markets. In the trades, however, many employers have been able to raise pay, train on the job, supply equipment, and generally bring their workers into true careers rather than a string of jobs—think electricians, utility workers, or welders. With retention comes a growing knowledge base within the business that becomes more efficient as time moves on. If educators choose, there exists the potential to drive new interest in training and educating young gearheads with accessible resources that prepare them to be efficient and adaptive technicians later in life, and demonstrating that it is a necessity to budget for new automotive education programs.

At the end of the day, our vehicles aren’t just expressions of passion and lifestyle. They are tools for survival in many ways, getting us to work, hustling our families from place to place, and offering escape when we need it. Their reliability isn’t just a matter of convenience, either; in many climates, our machines have to be in tip-top shape to deal with extreme temperatures and conditions. For many owners, that means a reliance on quality automotive care without having to navigate the complicated consequences of an industry that is in dire need of a tune-up.

While reading the article I came across the third picture with the dirty hand and the engine bay. The picture tells the whole story of being an auto technician. It’s all over. That car company stopped building cars years ago. Crappy car, crappy career. Want three weeks off a year. QUIT

The career How many techs can identify the car being worked on? The career just like the