Where do we preserve the old-school knowledge?

Much of what we do as automotive journalists, outside of serving the contemporary news and reviews, is record slices of history. People who work in hands-on trades know this in a different sense, passing along generations of technical skills between tradesmen as they enter green and grow under the wings of those who’ve completed the same journey years before. I think it’s a familiar experience for anyone working hard in the car community during their teens and twenties; it’s natural to be an outlier via youth until you’ve collected enough info and wisdom to share with the next generation of writers. Along the way, you collect information in slices—stories, tech data, photography, usually focused on a specific topic. And you share most of it online, because there are very few places left to print it.

Over time, that information becomes fragmented or lost due to the uncaring half-life of any internet content. There always comes some point at which a site is no longer hosted or a site update shatters an old story’s HTML format, practically erasing images and wholesale stories. This is a problem, one that is not getting better over time. How do we solve it? And via which medium? Which stands out as the most capable of keeping today’s hot rodding knowledge preserved for tomorrow’s historical reference?

The magazines carried the weight first

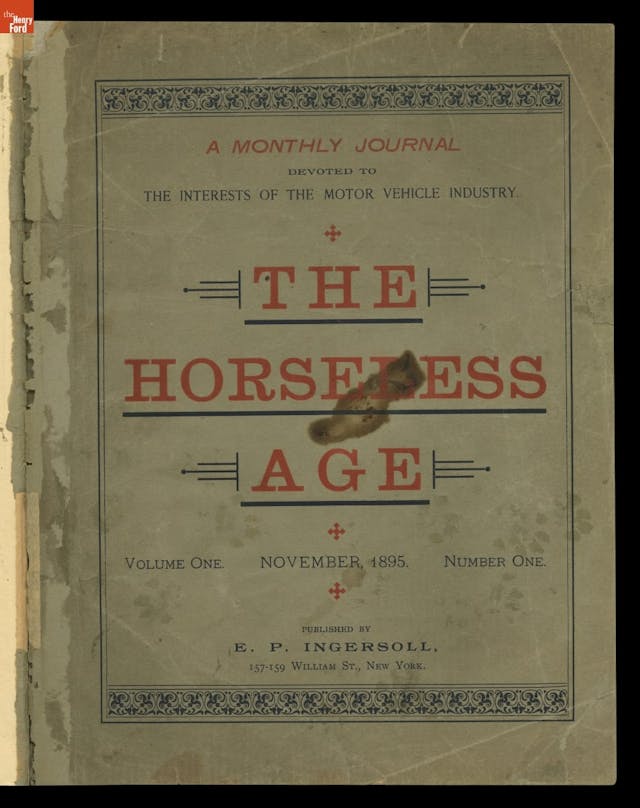

The first automotive magazine was published from 1895 to 1918. Titled The Horseless Age, the debut issue opened with a disposition on how the automobile had finally gone from years of cobbled-together experiments into legitimate products for purchase. By the end of his opening thoughts, after celebrating how there would be less literal horse waste in the streets, E.P. Ingersoll, the sole publisher, writer, and editor of this 418-page opening salvo to automotive media, had already considered print’s placement in recognizing, sharing, and preserving automotive history.

“An illustrated catalogue of the different vehicles built or projected here will surely be a valuable compilation, and this is what has been undertaken in this volume. Not quite all the motor vehicles constructed or now in process of construction will be found within the pages, but a large portion of them are here described. Imperfect as the record is it recapitulates one of the most memorable chapters of American innovation,” Ingersoll wrote. “The reader is requested to remember that in a compilation of this character it is the inventor or promotor who speaks, and not the Editor.”

Ingersoll couldn’t have been more on-point here; his original publication is now hosted online, stored in museums, and secure in the United States Library of Congress. What happened next? Well, many of the automotive media titles that we know today wouldn’t form until WWII veterans returned home and hurriedly created the hot rodding eras that inspired the likes of Robert E. Petersen and Wally Parks. Their roles as historians without an agenda were with a heavy focus as innovators, racers, and the movers-and-shakers of the auto industry, who became more accessible than ever to common people through their stories. Many of those same mag scribes would go on to write tech books, bios, and longer-form written content, further cementing their passed knowledge.

And, like The Horseless Age and every hard-copy publication since dedicated to the automotive industry, these works of journalism largely remain accessible and ever present. Collectively, today, there exists a body of knowledge that covers practically every person, vehicle, and piece of technology created over the last century, even in print magazines like Hagerty Drivers Club. No matter how large the wealth of knowledge is online, we unknowingly rely upon these generations of preserved materials to build our current understanding upon.

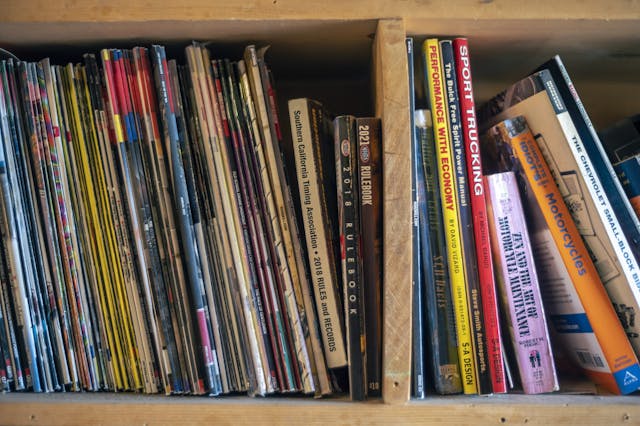

Unless my entire house burns down or someone decides to steal a bunch of recycling fodder instead of tools, I have my own archive of information like many others, bookshelves lined with magazines. Even in the golden era of magazines, however, it was obvious that there were some limitations to the format, most notably in terms of information volume and the ease of getting that information into print.

The digital era tried to pick up the excess

The internet had several advantages over print. Information could be shared without any physical barriers, discussion could be had about that info, and over time, it became the norm for users to self-publish instructionals and data without any gatekeeping from the publications. For gearheads, this was the first time they had keys to the asylum, and they moved quickly to open every door they could in the pursuit of knowledge.

Web 2.0, social media and YouTube

What was Web 2.0 anyway? It was the shift from special-purpose websites operated by the people who wrote there to user-generated content hosted by major websites. The shift came in part with the advent of high-speed internet making it less like sliding down sandpaper to upload content. Users didn’t need any computer programming knowledge, and having large resources behind the hosting meant a lot of the earlier inconveniences faced by individual gearheads trying to build their own website simply didn’t exist.

Once you had platforms like YouTube, Wikipedia, and Facebook (plus Instagram on the horizon), it was only a matter of time until their mass population would begin to absorb the automotive world’s knowledge base. Here is where a new form of self-published automotive media grew, and the case study I’ll use here is the Sloppy Mechanic’s YouTube channel. Matt Happel has become a mecca for low-buck turbo LS knowledge, taking the hook made by Westech Performance’s Richard Holdener writing “Big Bang Theory” in Hot Rod magazine of finding the limits of a junkyard LS engine and rolling that out like fresh dough into a master thesis of YouTube content. He had no real content agenda, simply posting his experiments, failures, and successful recipes with no real production value, simply setting a GoPro on a toolbox and sharing what he’s learned. To preserve that information, and make it easy to find, the Sloppy Mechanics Wiki was launched with detailed write-ups of his modifications for making a stock-block LS live at 1500 hp. There’s obviously a Sloppy Mechanics group on Facebook, where a community throws comments back and forth every few seconds to build each other up, keep each other humble, share their fights and failures, and keep the spirit of OG hot rodding alive through the mentality of going as fast as possible with simply what’s available, instead of always reaching for the “best” gadget.

This new culture essentially made drag racing more accessible than it had been in decades for gearheads; engines were a few hundred bucks a pop, the bare-minimum modifications had been tested, and those dang stock block grenades would be genuinely fast, getting new racers a little prize money quickly enough for them to invest into more durable engine combos. Plus, Matt’s work in this field has been routinely picked up by the established automotive media, further sharing his wisdom.

If you’ve been around the internet long enough, you know one thing is for sure: nothing is permanent. What exists today, what is more accessible than ever upon the depths of the most granular of topics, can disappear in milliseconds with no chance of saving it. Media websites reformatting their layouts, major hacks reversing websites to dusty and outdated back-ups, a megalomaniac forum moderator or admin deleting something out of spite — you name it. And the automotive community only received a true wake-up call here when the venerable hosting site PhotoBucket restructured and pulled the plug on every single embedded image it had tied to its free accounts, demanding a $500-ish ransom membership in order to gain hot link embeds back.

The response was violent, with thousands of messages, calls, and posts demonizing the company for putting fortified walls around content that they previously hosted for free over the past 10-15 years. It wasn’t just simple photos of someone’s car being lost, but detailed tutorial images, charts and data in .jpg form, unearthed photography from the pre-digital era that couldn’t be found anywhere else. The company would eventually compromise and return free image hosting at the expense of a water mark, but it shook the automotive community up with the realization that forums, a stalwart for decades, could be so easily lost to outside factors.

What’s next?

No matter how strong the current resurgence is in print right now, it’ll never be the bastion for technical information like it once was. The internet has been a blessing in making information more accessible than ever, but to get there, there has been an increasing dependence on outside factors to host and maintain the infrastructure that holds these digitized nuggets of knowledge. We do our best here at Hagerty to bring you the industry’s most comprehensive knowledge we can on classic car values, history, and tech — but there could be a day where it just all disappears just the same.

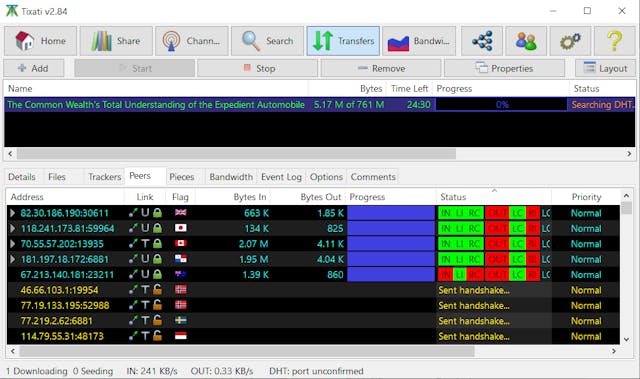

The future of online automotive knowledge could possibly depend on peer-to-peer (P2P) network sharing, and what’s been done to protect some of the more extra-legal websites from governments and record companies. In short, P2P networks are decentralized ways of sharing files online with no single host. Instead, the files are hosted on the PCs of users. When you want to download something, you obtain a torrent file that’s like a roadmap for your P2P software to go find it, uploading from a mass of individual PCs instead of a centrally hosted website.

In 2012, The Pirate Bay, a P2P network commonly used for downloading free copies of games, movies and music, published the source code and materials for their website as a torrent. The theory was that if their community had the tools to rebuild The Pirate Bay, there would be no way to kill it. There would surely be a community member ready to rehost The Pirate Bay’s search engine, and because the files people wanted to downloaded were hosted on other users PCs and not The Pirate Bay’s own server, that content couldn’t be lost. Legalities of sharing copywritten content aside, this model has also been shared by preservationists of all types to distribute and save an immense amount of media. Should we build an automotive bible, hosted through P2P means, with gigabytes of automotive technical and historical media ready to drop? It’s one idea, though it would take the cooperation of every automotive community’s knowledge to build this master file. The Library Congress cannot preserve every nugget held in a YouTube video or social media comment — neither can the wonderful Internet Archive— this would serve as your own international archive.

In the short term, I think that the route taken by Sloppy Mechanics to use different platforms to their advantage in discussion before cementing info in an easy to read Wiki page is great, but it still has problems if, say Google, randomly decided to kill their Wiki hosting and shoved off a community of users — something that major tech companies have clearly never been known to do before. Do we have the kind or parachute that The Pirate Bay has?

I don’t have the exact answer, but I do know that the status quo is shaky if we are to preserve what’s around us today. In my own decade-old career, I’ve seen my stories lost to the malevolent internet over time, and besides the ego dent, there are some technical stories with original information that have been lost forever. It’s painful to see something that once benefited others get ripped from their hands.

Where are you in all of this? Are you still getting your primary information through print media, or have you totally moved digital? Tell us in the community how you’d preserve a world of info and let’s see what we, as a population in the automotive culture, can build.