What low riding really taught us about the resilience of car culture

Every time a new car culture buds from the streets, there are those who want to prune it with regulation. Buried in most motor vehicle codes are these attempts to vilify certain unruly elements of vehicular expression. At best they’re bureaucratic solutions to problems and forces with deep community roots—the kind not easily controlled with difficult-to-enforce Band-Aid rulemaking. At worst, they serve as excuses to punish and supress.

History proves that these repressive efforts are more theater than action. Time and time again enthusiasts find a way, and in the process a new flavor of car culture flourishes. Today it’s street drifting with side-shows and take-overs that are currently in the spotlight, but at some point in the past, practically the entire spectrum of car culture has been in the crosshairs of mainstream society, from stage rallies or drag racing. Naturally, that includes low riding.

At one time, there was no such thing as a low rider. The idea of using hydraulic cylinders to alter the ride height of a car on demand, while today a central element of the low-riding archetype, didn’t even develop as an engineering solution to a technical problem—it was rooted in expression, and later, rebellion.

At the end of the 1950s, as America continued on a path leading to the civil rights movement of the following decade, California began to clamp down on car communities in the hopes of disbanding the impromptu cruise nights and crowds that were making headlines in NIMBY-minded newspapers. In particular, the focus of this negative attention was on urban Latinos. These communities were starting to develop their own subset of the established Kustom culture of the 1950s through the economic opportunities of East Los Angeles’ industrial might, a deviation that drew substantial ire from regulators. The powers that be blamed the clampdown on everything from neighborhood traffic to increases in crime.

Lowering cars for style was nothing new in and of itself, and Kustom culture had already become a rare, common meeting ground between car lovers of different ethnicities for the better part of the 40s and 50s through the fascination with making a car sit as close to the ground as possible. But increasing tensions between Southern California’s Latino communities (following the Zoot Suit Riots, especially) and whitewashing law enforcement certainly stand out as a catalyst for the effort that went into the ensuing crackdown on low riders. In this case, as in many others, a particular type of modified car became emblematic of a larger societal conflict.

Nowadays you can order a lowrider out of a catalog, but the L.A. guys sixty years ago were cutting or torching coil springs, Z-ing frames, and packing bags of concrete in the trunk in order to drop their cars onto the ground. These chassis-scraping antics were ways of standing out and expressing individuality. Needing a clean, legal basis to bust up cruise nights, California regulators began brainstorming creative measures.

In 1958, the first “lay low” law came into effect—a measurement between the lowest portion of a car’s frame and the lowest portion of its wheels within California motor vehicle code 24008:

“It is unlawful to operate any passenger vehicle, or commercial vehicle under 6,000 pounds, which has been modified from the original design so that any portion of the vehicle, other than the wheels, has less clearance from the surface of a level roadway than the clearance between the roadway and the lowermost portion of any rim of any wheel in contact with the roadway.”

In short, if the car was modified such that the frame rode lower than the bottom lip of the wheels, that vehicle was no longer street-legal and subject to impounding and fines. In the following year, California brought in motor vehicle code 24400, further regulating vehicle ride height through the distance between the ground and the headlamps:

“A motor vehicle, other than a motorcycle, shall be equipped with at least two headlamps, with at least one on each side of the front of the vehicle, and, except as to vehicles registered prior to January 1, 1930, they shall be located directly above or in advance of the front axle of the vehicle. The headlamps and every light source in any headlamp unit shall be located at a height of not more than 54 inches nor less than 22 inches.”

Armed with the legal basis to define a vehicle as unsafe, California’s leaders had a fresh tool for law enforcement to bust up low rider cruise nights. In response, the burgeoning low rider community came up with the solution that would go to define the ingenuity of their genre.

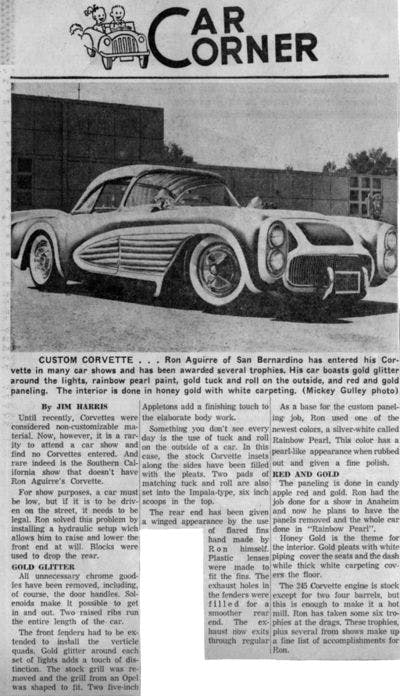

Ron Aguirre is often credited as the innovator who first looked at a body shop port-o-jack and the stockpiles of war birds retired after WWII and saw a solution: hydraulic cylinders could easily lift an offending car off the ground once The Man’s prying eyes came threatening. Aguirre’s custom 1956 Corvette, known as X-Sonic, was targeted heavily by local cops, and using hydraulics became his way of teasing officers. As he told the Lay It Low forums in 2001, Aguirre recounted one notable reaction by an officer that frequently gave him a hard time:

“But it wasn’t until 1959 that I was able to raise a lot of hell with the system the way it was and I was going to drive ‘Sandy’ the cop crazy. We waited for him to ride his bike to his spot across the street from the local hangout in Berdo, Ruby’s Drive-in. I was parked on the lot with my car lowered way down. There were about 100 of my school friends at the drive-in waiting to see what would happen. I left the car down and started to drive out and the side pipes were scraping the pavement (It was way cool to have your car dragging on the pavement.) I had my girlfriend get out and my buddy got in with the instructions to pump hard on the handle of the pump as soon as I gave him the word. Well, knowing ‘Sandy’ was across the street and waiting for me to leave the restaurant so he could give me a ticket in front of all my friends and teach them that this punk was not going to get away with breaking the law, again. I pulled out onto the street and watched Sandy start his bike, I told my buddy to start pumping. I didn’t get 20 feet and Sandy had his red lights on me. I got out of the car and everyone from the drive-in was standing on the sidewalk. I greeted “Sandy” by name, as no one called him Sandy to his face. “Hi, Lester, what seems to be the problem?” He stated, ‘You know your car’s too low.’

‘But Lester,’ I said, ‘it isn’t too low any more, I took your advice and raised it to legal height.’ He smiled at me and took his ticket book. Back then, this is how the cops checked cars. If their ticket book did not pass freely under your car you would get a ticket, and he slid it under my car without hitting anything. Boy, was his face red and with all the witnesses yelling and screaming, he didn’t say a word, he gave me a confused look and got on his bike and left.”

The culture of low riding took this very same personality of skirting these targeted regulations, or others written in the same vein. Local municipalities attempted again to squash low riding with anti-cruising laws on particular streets, citing anyone on such grounds as passing a particular sign multiple times within a certain time period. One look around the area today proves how futile these efforts were, and in many cases these sorts of punitive measures have become much more of a blight in the history of So Cal—which today prides itself on preserving the diversity of its people—than the cars or cruising ever did. In subtle (or arguably not-so-subtle) ways, low riding stood for resistance and protest, even as the culture matured into the more established, organized genre its adherents enjoy today, complete with its own footprint of established events, media, legends, and heroes.

Headlines about some form of harmful new car culture persist in 2021, and states like California continue efforts to enforce things like exhaust noise laws (think 2018’s defeated AB 1824) to push them out. If the history of low riding can be taken as a guide, these efforts won’t accomplish anything but push the communities to more elaborate expressions of their identities.

In every form, from organized motorsports to clandestine street meets, car culture is a social matrix as much as it is a collective love of machinery. For more than a century now, it has forged and strengthened bonds between different streets, neighborhoods, countries, lifestyles, demographics—each genre within car culture is a potential haven for anyone seeking to find comfort from the often harsh realities of life. Attacking a means of expression, instead of understanding and addressing the source of its necessity, is a hopeless endeavor. Someone will always show up with the proverbial hydraulic cylinder around which to rally.