Think batteries are bunk? Hydrogen’s long-term prospects aren’t much better

Automakers rarely agree on anything, but several are seriously considering the possibility that hydrogen will eventually power all of our road-going vehicles. That would make the transition to battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) merely a waypoint on the road to truly green transportation.

Hydrogen is the most abundant material in the universe. Our Sun is hydrogen in the plasma state (electromagnetically charged gas). On Earth, hydrogen exists in water (H2O) and in organic compounds such as methane (CH4). Unfortunately, Mother Nature’s most prodigious fruit requires considerable effort to harvest. Like gasoline, hydrogen must be refined to prepare it for service as a portable fuel.

Two centuries ago, Great Britain’s Reverend Cecil was the first to use hydrogen to fuel an internal combustion engine. Before carburetors arrived, the German Nikolaus Otto, inventor of the four-stroke combustion cycle, considered gaseous hydrogen safer to use for experimentation than the gasoline that existed in 1870.

Today we know that hydrogen is easily ignited, it can be used over a broad range of air-fuel ratios, and high compression ratios are feasible—resulting in high thermal efficiency—because of hydrogen’s elevated auto-ignition point compared to gasoline. A notable downside is that combusting hydrogen with air produces NOx, a subset of troublesome greenhouse gases. Nonetheless, Mazda built a rotary (Wankel) engine fueled with hydrogen for evaluation. Ford and BMW both used piston engines for their hydrogen experimentation. BMW’s Hydrogen 7 achieved 187 mph in straight-line runs and its H2R streamliner, powered by a liquid-hydrogen-fueled V-12, set nine international speed records. Hydrogen-fueled applications ranging from forklifts to city buses, boats, and aircraft have also been examined.

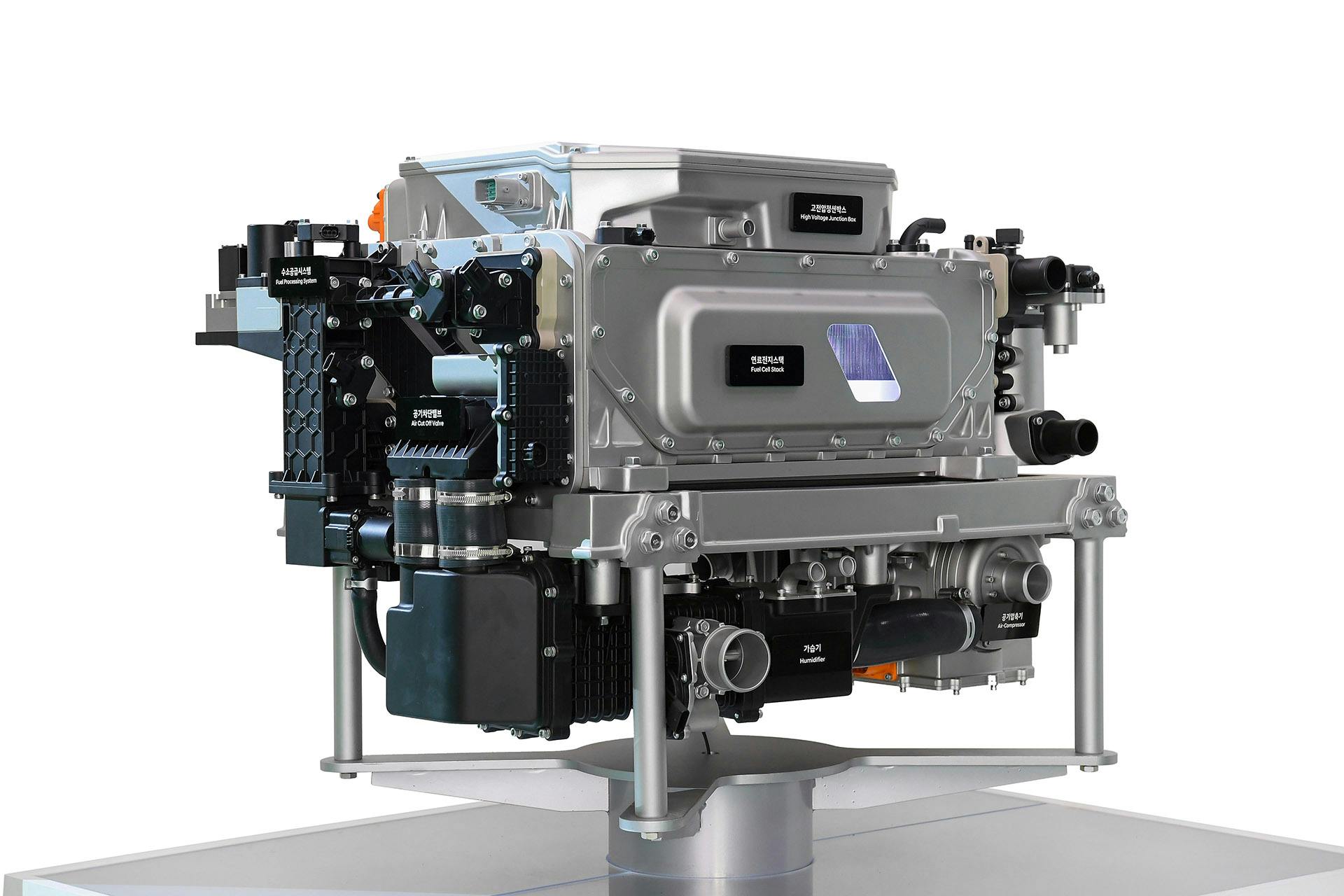

Today’s more popular gambit is to use hydrogen gas, stored onboard the vehicle, and oxygen, drawn from the atmosphere, in fuel cells to produce the electricity needed to power an electric motor. Scientists began studying fuel cells nearly two centuries ago and NASA has used them to power satellites and space capsules for sixty years. Like batteries, fuel cells generate electricity with the flow of electrons from an anode to a cathode through an electrolyte inside a sealed chamber. A catalyst of some sort accelerates this chemical reaction which yields a DC current with water as the only byproduct. Since carbon plays no role in this energy conversion, no harmful CO2 is produced. A power inverter converts the DC current from the fuel cell to AC for the vehicle’s drive motor. A battery is necessary to provide the instant energy needed for bursts of acceleration because a fuel cell’s response to demands for more output is lackadaisical. Fuel cell catalysts are most often platinum, one of the most expensive materials on Earth.

The most common means of producing hydrogen is to expose hot, pressurized natural gas to a catalyst to convert it into hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. Electrolysis of water is an alternative method. While hydrogen gas is a natural byproduct of some nuclear powerplant processes, that form of energy generation is unfortunately out of favor these days.

Through 2019, more than 18,000 fuel-cell-powered vehicles had been sold or leased worldwide. They typically offer 300-plus miles of range and refueling in five minutes or less. In 2013, after 15 years of R+D, Hyundai set the fuel cell stage with a few converted Tucson FCEV crossovers, followed by the Hyundai Nexo SUV in 2018 for California only. The first dedicated fuel cell model was Toyota’s Mirai sedan launched in 2015, followed by a fresh second-generation design for the current model year. Honda’s Clarity four-door is currently available for lease in California for $379 per month, but given that the model has been effectively killed after the 2021, it won’t last much longer.

Given the cost of advancing the state of the technological art, manufacturers typically partner with one another to share development costs. In the fuel cell domain, GM has a longstanding relationship with Honda. BMW’s licensing agreement with Toyota dates to 2013. Ford teamed with Mercedes and Nissan that same year.

The Hyundai Motor Group (HMG), deeply committed to hydrogen fuel and fuel cells, recently announced what it calls a “Hydrogen Wave for everyone, everything, everywhere.”

In early September, HMG chairman Emulsan Chung proclaimed, “Our vision is to apply hydrogen energy in all areas of life and industry such as our homes, workplaces, and factories. We want to offer practical solutions for the sustainable development of humanity and with these breakthroughs, we aim to help foster a worldwide Hydrogen Society by 2040.”

Specific HMG game plan initiatives are:

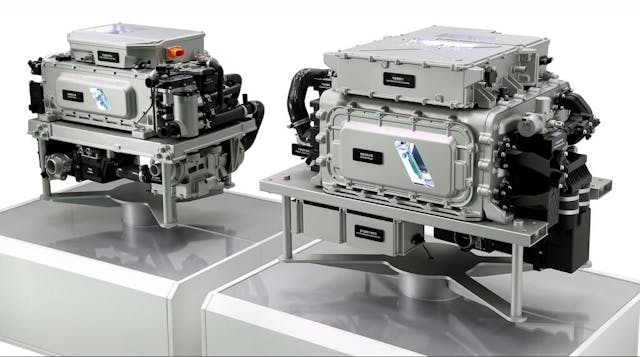

- Two third-generation 100 kW (134 hp) and 200 kW (238 hp) fuel cell systems by 2023 demonstrating twice the power, 50 percent cost reductions, and 30 percent smaller volume than the company’s gen-two designs.

- To become the world’s first manufacturer to apply fuel cell systems to all its commercial busses and trucks by 2028.

- To match the price of a BEV with a fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) by 2030.

- To apply fuel cells to all types of mobility while extending hydrogen technology into homes, buildings, and powerplants.

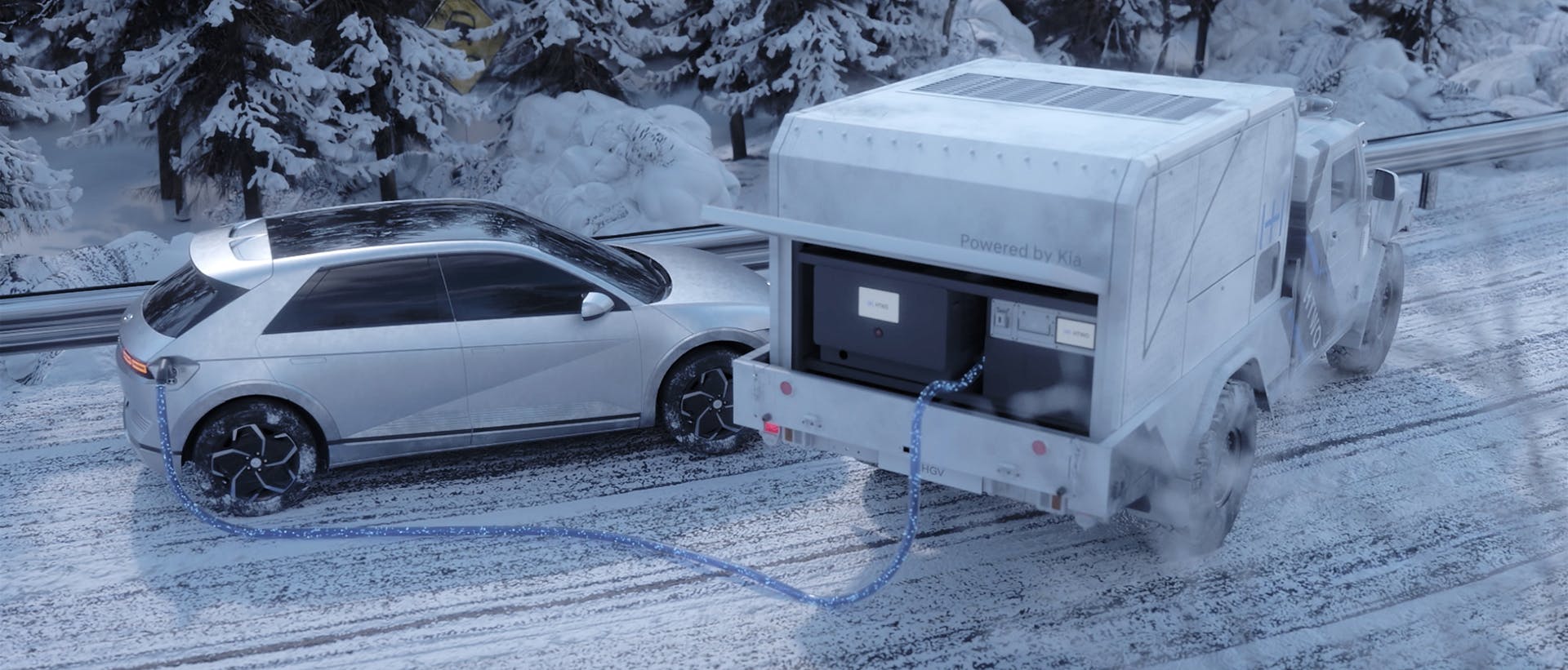

Proving HMG is serious about this major commitment, chairman Chung unveiled a 570-hp Vision FK high-performance sports car (unfortunately camouflaged), a huge autonomous Trailer Drone vehicle, and a fleet of emergency rescue vehicles—all powered by fuel cells and all intended for production. Another HMG invention is the H-Two, a portable hydrogen fueled charging station intended for emergency power at remote locations.

To gauge the likelihood of HMG’s hydrogen dream coming true, we referenced it to current attitudes on this subject. A credible point of view comes from the Hydrogen Council (HC), a global organization founded in 2017 and led by 92 CEOs from leading energy, transport, industry, and investment firms. This organization expects that hydrogen will account for 18 percent of the global energy demand by 2050, that CO2 emissions will be diminished by six billion tons annually, and that 30 million new jobs will be created.

Bill Visnic, Automotive Engineering magazine’s editorial director offered a less sanguine point of view:

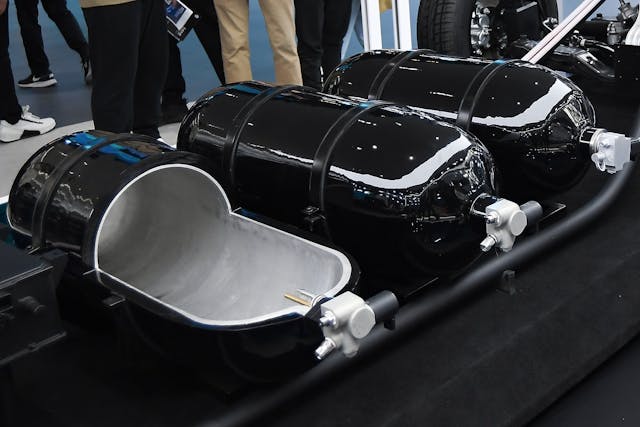

“Commercial vehicles definitely represent the path of least resistance for the adoption of FCEV technology. Their longer service lives make it easier to amortize the high costs. Larger vehicles are better suited to the bulky, heavy tanks needed to carry the hydrogen fuel.

“Given the major R&D investments under way, it’s realistic to assume that fuel cell cost, efficiency, and power output will see dramatic improvements. That said, matching the cost of BEVs will be difficult given the concerted efforts of both the auto industry and the global battery makers that are progressing. Bottom line: HMG faces major challenges advancing hydrogen’s cause.”

Addressing the weight of portable hydrogen storage tanks, Jeff Sloan, editor-in-chief of CompositesWorld magazine notes that “During the past year, hydrogen has vaulted near the top of the non-petroleum-energy source list, joining wind, solar, and hydro energy. Programs using hydrogen to power long-haul trucks, busses, trains, cars, and aircraft are advancing rapidly around the world and carbon fiber has become a prime candidate for hydrogen pressure vessels. Unfortunately, the supply chain is not sufficiently evolved to quickly and easily respond to emerging opportunities. So one must wonder if hydrogen expansion is real and sustainable.”

Inevitably, a few hydrogen naysayers have surfaced. Volkswagen believes that fuel cells have “no future in the automotive market.” Mercedes-Benz recently backed out of its cooperative fuel cell agreement with Ford and Nissan. And the learned Elon Musk has dubbed this technology “fool” cells out of skepticism that hydrogen will ever be a practical automobile fuel.

There are other issues to consider. The range anxiety currently frustrating BEV adoption may persist when HCEVs arrive with their own operating limitations. And, given the challenges President Biden is facing raising funds to build BEV-charging infrastructure, his successor won’t have it easy investing in hydrogen generation and distribution systems. The Hydrogen Council estimates that $300-billion in global spending will be required to expand infrastructure by 2030.

Last, mere mention of hydrogen gives some consumers the willies. Many of them recall Nazi Germany’s Hindenburg fiasco, while others associate hydrogen with thermonuclear bombs. Even if HMG is somehow proved correct in the long run, the company is bound to suffer some major wipeouts while surfing its Hydrogen Wave along the way.