When Cars Attack: Cautionary Tales from The Hack Mechanic

As I’m not wrenching much this winter (a situation caused by not really having a proper winter project, as well as using that as an opportunity to give my nagging back injury a chance to heal), I thought I’d write about the spectrum of wounds, cautionary tactics, near misses, and emergency room visits that the decades of wrenching have produced. Considering the amount of wrenching I’ve done over the past 45 years, I’ve had surprisingly few serious injuries—no ambulances have visited my house. But there has been blood and one near catastrophe.

Cautionary Tactics

Racers talk about losing their judgement when the red mist (adrenaline) flows and they begin doing things they know they shouldn’t do. When you’re removing some stuck bolt or recalcitrant component, it’s easy to get influenced by “mechanic’s red mist” and go all Cole Trickle on it (“This part is goin’ DOWN!”). Because of both impaired judgement and the larger forces at play when you’re pushing or pulling hard, this is when you’re likely to hurt yourself. For example, when gripping on a wrench or a ratchet handle and pushing it to loosen a bolt, if the ratchet slips or the bolt breaks, it’s the back of your hand that’s likely to smack against something sharp or pointy. The tendons back there are very close to the surface; you can plainly see them whenever you flex your fingers. Pushing a wrench or ratchet with the open palm of your hand instead of the closed fist can make the difference between a few stitches versus surgery and months of physical therapy.

Helicoptering up a bit, it’s good to be in the habit of approaching any repair with a degree of situational awareness. What are the hazards in the area you’re about to stick your hands into? Are there jagged edges? Hot hoses? Frayed wires or ends of cables that can cause a painful puncture that gets infected? Are there rotating parts you need to be aware of? Is the thing that you’re removing going to drop down and pin your hand? Simply taking a moment and scoping this stuff out is time well spent.

The phrase “gas and spark” is often used to describe the necessary precursors for an internal combustion engine to run, but it’s also a cautionary phrase, as you really don’t want these things combined outside of the engine’s combustion chamber. Spilled or leaking gas can easily be ignited by a stray spark from either an electrical connection being made or broken, or cutting something with a spinning wheel. So don’t, for example, use a Dremel tool to cut a metal clamp off a fuel hose.

But that’s all small stuff. In my opinion, the most serious vector for automotive injuries is jacking up a car and working under it. I believe I’ve told the story on these pages about how my physics professor for my sophomore mechanics class (and part of mechanics is statics—the study of the forces on things that aren’t moving) was killed when his car fell on him, forever imprinting on me that intelligence and common sense don’t necessarily go hand in hand. To be fair, I don’t know the details of what went wrong, but ever since that event, I’ve “double-jacked” cars. That is, if you’re going to crawl under a car, be sure to put it on a hard level surface (concrete, not asphalt, and definitely not hot asphalt), jack it up, position the jack stands, let it down onto the stands, and then leave the floor jack in place as a backup.

Near-Misses

There are five that stand out.

The lift incident: By far the scariest thing that ever happened to me while fixing cars was the time my mid-rise lift nearly killed me. A chain of three unlikely events—the design of the lift that makes it possible to defeat the safety latch (the thing that supports the weight of the car mechanically instead of relying on the hydraulic pressure in the cylinders), my having flipped that latch and not flipped it back into the auto-lock position, and, while I was under the car, my legs having accidentally kicked one of the car’s removed wheels, by pure chance sending it rolling into the lift’s pressure release lever—caused the hydraulics to depressurize and the lift to slowly drop while I was under it. Fortunately, I was under the back of the car, and due to it coming to a stop on its brake drums, there was enough space that my chest cavity didn’t get crushed. (You can read the details in the link above.)

At the time, I was stoic about it and simply finished the repair, but with hindsight, I could’ve been killed, and I’d be lying if I said that that didn’t rattle me. Obviously I no longer move the latch from its auto-lock position, and I’m assiduously careful to make certain that, when a car is on the lift, the lift is resting on one of the stops and not on hydraulic pressure.

The jack incident: While not nearly as serious as the lift incident, the jack incident viscerally demonstrated the importance of jack safety. On a hot late-summer day, I drove down to Cape Cod to have a look at a BMW 5 Series wagon. I met the seller in a CVS parking lot. I noticed that the lot was asphalt and had a very slight grade but didn’t think too much of it. I’d brought a medium-sized aluminum floor jack to check for front-end play, so I slid it under the nose of the car, found the jack point under the subframe, and gave it a few pumps to get the front wheels high enough to wiggle. As I was checking the first wheel, the seller said, “Look out, look out, LOOK OUT!” The combination of the jack sinking into the hot, malleable asphalt and the slight grade caused the car to topple off the jack and toward me. I was never in real danger—I was wiggling the wheel with no part of me under the car—but it alarmed both of us. Whenever I think about swapping a wheel with a car supported by only a jack, I remember this incident, and reconsider.

The wiper linkage that pinned my wrist: Decades ago, I was troubleshooting the non-functional windshield wipers on my BMW 3.0CSi. Doing so required me to pull the multi-prong plug off the wiper motor, turn the key to the accessories setting, switch on the wipers, and check for voltage and ground at the connector using a multimeter. When I was done, I pushed the connector back onto the wiper motor, which rewarded my efforts by suddenly springing to life. When it spun, it rotated the wiper linkage, which pinned my wrist against the piece of metal that the wiper motor mounts to. I’ve recreated the event in the photo below, which was instructive because the way I remembered it, it was the act of reaching in and plugging the connector back in that put my wrist in a position where it could’ve gotten pinned, but now I see that that’s highly unlikely. Regardless of exactly how it happened, my wrist was pinned, and the motor was still on.

The incident occurred in the late 1980s when my wife and I were still living at my mother’s house in Brighton. I stood there, watching my hand turn white as the unrelenting torque of the wiper motor cut off the blood flow and stood a good chance at slicing open my wrist, but because the garage was on street level and the house was a flight up from the sidewalk and my wife’s and my apartment was up on the third floor, my calls for help went unanswered. Fortunately, while looking around the engine compartment, I saw a wrench within reach, and I was able to use it to undo the negative battery cable, which killed the power to the wiper motor. Even with the power cut, though, it took quite a bit of wiggling to extricate my hand, and when I did, the crease on my wrist looked like a dull guillotine blade had bounced off it.

The vise that attacked my foot: I was installing a new exhaust in my car, replacing every piece except the catalytic converter. Unfortunately, one of the bolts holding the cat to the resonator was frozen in the flange and needed to be drilled out. At the time I didn’t own a drill press, so I put the cat in my car, changed into summer clothes, drove into work, and used the drill press there. I clamped the flange into a vise that sat on the flat surface of the drill-press table. The vise wasn’t secured to the table, though; it was free to move, allowing you to line up the drill bit with its target.

Drilling out a bolt is slow work, I got impatient, the mechanic’s red mist got the best of me, and I leaned a little harder on the drill press lever. I saw a little whisp of smoke, heard a little chirp from the bit, and then the bit grabbed the flange, causing both the catalytic converter and the vise to rotate and throw themselves on the floor. They landed about six inches from my left foot. As I looked down, I saw that I was wearing sandals. IDIOT!

Emergency Room Visits

It’s the two head wounds that rise above the background of hand stitches and metal filings and rust removed from my eye. Head wounds, of course, generate a lot of blood, making them very dramatic. And these two incidents were just so stupid.

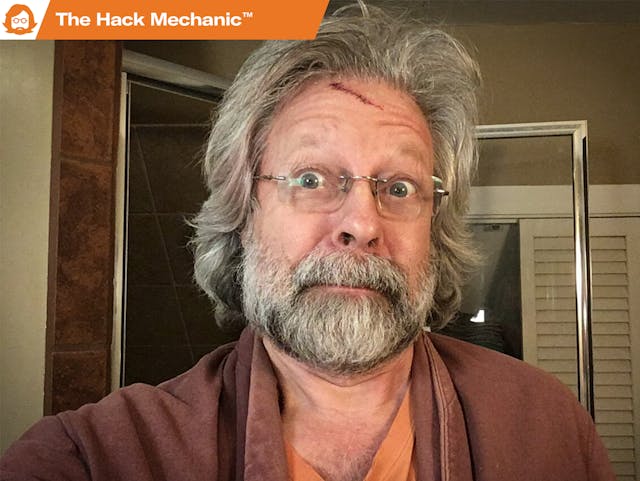

Chevy Suburban rear hatch: The gas struts on the rear hatch of my 2000 Suburban were getting weak, resulting in the hatch slowly closing after you raised it. I replaced one of them, smiled to see that the hatch was now holding itself up, reached inside the truck to get the second strut, didn’t expect the hatch to begin sagging during those few seconds, turned around, and the corner of the lowered hatch caught me right across the scalp line. I grabbed a handful of paper towels, mashed it against the wound, and staggered toward the house. A few minutes later my wife and kids arrived home to find me sitting on the front stoop with blood dripping from my face. “Father down!” I said. “Father needs assistance!” My wife looked at it and said, “Hospital, now.” (photo above)

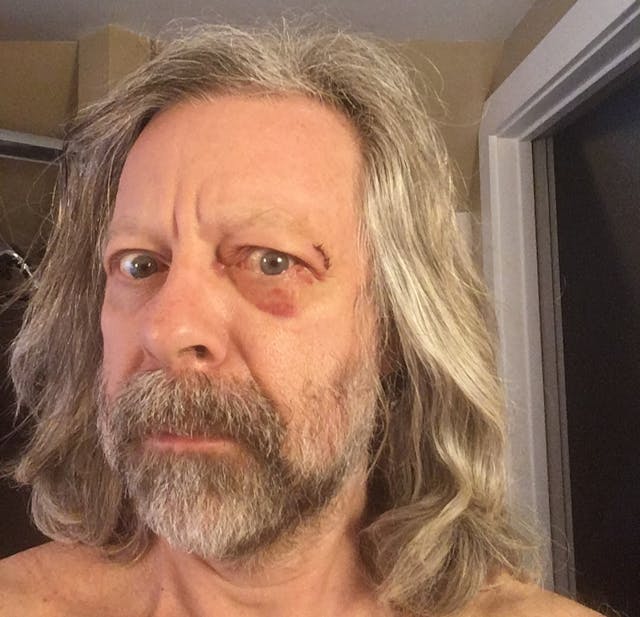

The vicious driveshaft: I don’t work on other people’s cars for money, but I do favors for friends. The problem is that the more often you do this, the more you open up the possibility of something going wrong. In this case, prior to a road trip, one of my traveling companions asked if I could revive the A/C system in his BMW 2002. A pressure test revealed a single bad o-ring, so with a pump-down and a recharge, he had a cold car. But when we test-drove it, I noticed a very large amount of play in the shift lever. Tightening it up is usually a quick repair, so I put the car up on the lift and crawled under it while he moved the shift lever around. There are two metal-and-rubber bushings holding the shift platform to the back of the transmission, and the Allen-head bolt holding one of them had backed its way out. This was the left-hand bolt, which is usually the one that you’re able to get an Allen-key socket onto by using a wobble extension, but there was something about the five-speed installation in this particular car that made accessing that bolt difficult. Plus I could see that the hex hole was stripped. So to get at the bolt and replace it, the front of the driveshaft needed to be dropped.

It was the end of a long day of wrenching, and I was on automatic pilot. I undid the bolts securing the driveshaft’s center support bearing, and the three holding the giubo (the rubber flex disc) to the flange on the back of the transmission. I began lowering the driveshaft but immediately found that it hit the exhaust. Fortunately, the bolts holding the resonator to the exhaust headpipe weren’t seized. Unfortunately, as soon as the resonator was lowered, the center of the driveshaft dropped with it, which freed the front of the driveshaft to swing down and clonk me right in the face, just above my left eye.

Garage wounds fall into three categories (emphasis on the gory): 1. Press on regardless, 2. Non-urgent car ride to urgent care clinic or emergency room, or 3. Ambulance. I asked my wife to triage me. “It’s not awful,” she said, “but it’ll need stitches.” I asked her to call and find out the hours and the co-pay of the nearest urgent care facility and to put a gauze pad and tape over the wound so I could finish the repair, which only took about 15 minutes. My friend graciously paid the quoted $35 co-pay, and we joked about whether a medical facility had a standardized insurance code for “hit in the face by a driveshaft.” (A doctor-friend later told me that the code is likely W20.8xxA, “struck by thrown, projected, or falling object,” along with Y92.015, “private garage of single-family house as the place of occurrence of the external cause.” He then joked, “For completeness sake, I would probably add Z74.3: Need for continuous supervision.”)

That’s most of it. Except for the time I ran over my own foot, but I think I’ll stay mum on the details. I mean a guy has to have some secrets.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Glad I am not the only one. Very relatable – will spare you any details. However, part of my forum signatures include this comment: “It’s not YOURS until you BLEED on it”

I almost had a torque wrench take out my eye once. I was working on replacing the rear subframe on my Jeep and near the end of the project I was torquing down the lower bolt on the lower control arm when the wrench slipped off the bolt (I was pulling it towards myself, mistake #1) and it slammed into my safety glasses. So that’s why everyone says to wear those…

Vise, not vice.

you have your fun – I’ll have mine… 😜