I’m not sure how it happened, but my truck is a zombie

As some of you know, I have a 2008 Chevy 3500HD dually with the Duramax diesel and a utility body on the back. It was owned by the company at which I spent my 30+ year geophysics career. It was purchased new, and we used it to tow a 32-foot trailer loaded with purpose-built geophysical surveying equipment designed to find unexploded ordnance (dud bombs) on old military training ranges.

I’m no truck driver, but someone needed to drive the rig to job sites, and since I needed to be there anyway, a trucker friend taught me just enough about backing up a trailer that I became competent enough to drive it, as long as I didn’t need to do one of those back-up-and-block-traffic-and-nail-the-loading-dock-perfectly-on-the-first-try maneuvers that pros do.

But by 2013, most of the geophysics work had dried up. The company closed the building I worked in, and the remnants of my team scrambled to find small inexpensive industrial space. The truck had a short second life towing a boat that the company had for another geophysics project, but after that, the truck, with only 28,000 miles on it, largely sat.

In 2015, I left my full-time job there and became the writer that I remain, but until this year I maintained a consulting agreement with the company. In an unofficial favor-with-benefits arrangement, I kept the truck inspected and registered on the company’s behalf and, yes, occasionally used it to tow cars under the auspices of “keeping the equipment exercised.” A few years ago, when it was clear that the geophysics work was completely dead, I made them a low offer for the truck, trailer, and equipment. Initially they said “yes,” but reneged when they found that the truck was still on a corporate depreciation schedule.

Last year, the company abruptly closed the small industrial space and liquidated everything inside. The truck and trailer were kept in a paid storage lot a few miles away and thus were spared the liquidating axe, but the company didn’t really know what to do with them (or, for that matter, even what they were and how they were originally used). And by then, years of outdoor storage had taken a brutal toll on the truck, as mice had gotten in, and the thing smelled like an abandoned slaughterhouse. I photographed the damage, which included brown fluid literally dripping out of the headliner and sent it to my former employer with an almost criminally low offer and a note saying, “You should’ve sold it to me when it was worth something. Now it’s not. Take it or leave it.” It took them a few months, but they accepted the offer.

So, last spring, for the cost of a 20-year-old rusty Suburban, I officially became the owner of a Duramax diesel with only 28,000 miles on it.

Job One was, obviously, to de-mouse the thing, whose smell would’ve gagged a maggot. About a year ago, I wrote a series of articles about “the mouse-infested truck” (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4). By replacing the headliner and drilling a hole in the heater box to remove the mouse nest and bodies (I was unwilling to go to the level of effort required to pull the box), I knocked the smell down to a very tolerable level so I could drive it, although I was smart enough to never ask my wife to ride with me. I replaced the dry-rotted tires and changed the oil and the fuel filter, but with the car’s mileage still under 29K, it didn’t seem to need anything else.

Owning 13 cars, even with five cars stored in rented warehouse space on the Massachusetts-Connecticut border, my driveway gets congested. When I bought another BMW 2002 last spring that clicked the total vehicle count up to 14, I put the word out that I needed a nearby parking space for the truck. A friend responded that he rents five spaces at a dance studio about a half-mile from my house and offered me one of them for $50/month. It was perfect. The truck was just a short walk away. Since I didn’t drive it often, I’d leave it with the batteries disconnected. If I needed to use it, I’d hoof it on over, unlock it, reconnect the batteries, and fire it up.

As it happens, I haven’t used the truck to tow as many cars as I’d expected. I dragged my 49,000-mile BMW 2002 from the old storage space to the new one at the start of last winter. And, when I took delivery of my friend Chris’ 1972 BMW 2002tii, which I just sold for her on Bring a Trailer (“the mitzvah car”), I towed it home rather than risk the hour-long drive on unsorted mechanicals and 14-year-old tires. But that’s been it. With the big Duramax diesel, the Allison six-speed transmission, and the dually wheels, this is a rig that could pull one of those four-car haulers. Using it mainly to run cardboard boxes to the dump, pick up well-priced wheels and Recaro seats, and occasionally help my nieces move between apartments is massive overkill, but hey, they’re called crimes of opportunity for a reason.

But I do enjoy owning it. And it’s been dead-nuts reliable. Unlock the door, unlatch the hood, connect the batteries, twist the key, and go.

That is, until last week.

My wife is an avid quilter and recently bought a large free-motion quilting sewing machine and the table to go with it. She asked if we could use the truck to pick it up (we joke that her goal is to own as many sewing machines as I own cars, and she’s well on her way). I said that that was, of course, fine, but cautioned that her exquisitely sensitive sense of smell would undoubtedly pick up on the truck’s residual rodent aura. She said, good-naturedly, “I’ll bring a mask.” We walked over to where the truck was parked, I hooked up the batteries, turned the key, and the big Duramax snapped to attention. Then, to my surprise, it suddenly died two seconds later and would not start for love nor cranking.

To handle the immediate quilting-related need, the combination of my wife’s Honda Fit hatchback and my BMW E39 530i’s fold-down rear seats moved the sewing machine and the table. When we got back, I examined the truck.

The old-school adage is that starting requires fuel and spark (well, more like fuel, spark, air, compression, and timing). Of course, there’s no spark on a diesel, but a modern diesel has an ECU controlling the injection. Still, the smart bet was that the no-start was a fuel delivery issue. I know very little about diesels in general and the Duramax in particular, but I verified that the fuel filter was tight, then re-primed it and bled the air out with the plunger button on the top. It made no difference.

I really dislike using my phone for troubleshooting; if I’m going to pore over user forums, I’d much rather sit in front of the laptop. Fortunately, with the dead truck so near my house, it was easy to do a little online research, walk or drive to the parking lot of the dance studio, open up the hood, reconnect the batteries, try one thing, then close it up and head back home. I checked for fuel leaks and collapsed fuel lines but didn’t see any. Friends advised that the problem was likely in the electric lift pump, but this vintage Duramax (2008 with the LMM engine) doesn’t have one. I verified that certain ECU fuses weren’t blown and swapped certain relays. None of made a difference. The engine cranked easily but made no attempt whatsoever to start.

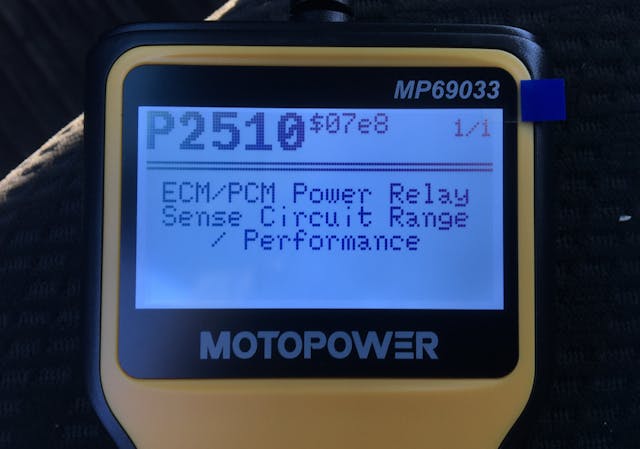

The next step was to check for codes. My old Actron OBD-II code reader has, for reasons unclear, never recognized the truck, so I ordered a $25 code reader on Amazon. When it arrived the next day, I reconnected the batteries, plugged in the code reader, cracked the key to ignition, and was presented with a P2510 code.

Anyone who has used an OBD-II code reader knows that codes generally fall into one of two categories—instantly useful and “what the hell does that mean?” In the former category, I’ve found that misfire codes usually pay for the code reader in just one use—if it says “Misfire on cylinder #2,” pull off the false valve cover, swap the coil-on-plugs for cylinders #2 and #3, clear the code, start the engine, and if the code moves to cylinder #3, replace the coil-on-plug, boom, done. On the other hand, the dreaded P0456 (“minor evaporative leak”) code can leave you pulling your hair out if you need to fix the underlying condition and clear it in order to have the vehicle pass inspection. So it depends on what the code is and how clearly it leads to a specific cause and a course of action.

Many of us who are not professionals rely on user forums to crowd-source this kind of diagnostic information. If your vehicle has a problem and is throwing a code, and if 90 percent of the posts on a user forum for the vehicle say “It’s the borfin control valve, I replaced mine and the problem and the code went away” and if said borfin control valve is a $30 part, most of the time throwing $30 at the problem is money well spent. Pros may decry this kind of parts-swapping, but I’ve found that if there’s a clear consensus in the posts, it usually works pretty well.

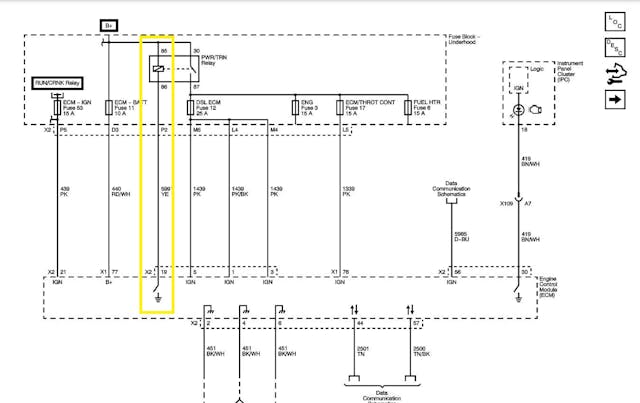

Unfortunately, when I did a deep dive into the Duramax forums, I learned that the P2150 code is in the “what the hell does that mean” category. Even though the code says “ECM / PCM Power Relay,” the consensus on the forums was that the code very rarely means that there’s a problem in the relay itself, and instead is usually indicative of a chafed power wire, a bad ground, or corrosion inside the fuse box.

Great.

Now, I’d been posting all this on Facebook in near real time. My friend from whom I sublet the parking space saw my reports on the dead truck and sent me a message saying that his lease explicitly forbids working on vehicles in the lot and cautioned against anything but the quickest of hood-up hunch-confirmations. “Heard and understood,” I replied. “No filter or fuel hose replacements, no dismantling the fuse box. Got it.”

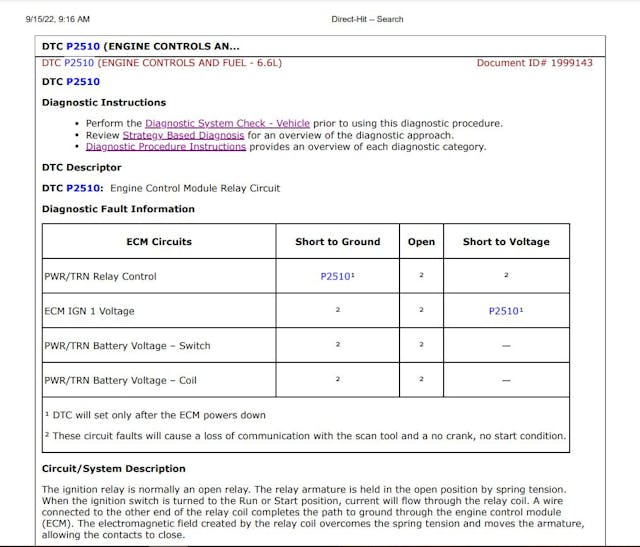

Another friend who is a pro saw my post, asked for the truck’s VIN, and ran the code in Identifix, which, like Alldata, is a subscription-based database of troubleshooting information. He sent me the P2510 test plan for the truck. I greatly appreciated it, but reading it made my eyes cross, as the test-plan-ese it’s written in may be easily understandable to certified technicians who are used to reading these things, but I’m more a seat-of-the-pants guy (Yes, I know, it’s ironic that I, who wrote an automotive electrical book, don’t take to test plans and wiring diagrams like a duck to water). I’m all for a systematic diagnostic approach when it’s necessary, but I’ve also seen Alldata-generated approaches not only fail but cause damage—I’ve bought dead cars where someone has clearly gone full Alldata on it and cut open the wiring harness and the rubber boot on the connector feeding the ECU so they could back-probe the pins, when all that turned out to be wrong was that the distributor cap was missing the little spring and carbon nub that’s supposed to make contact with the rotor.

However, I had to admit that since my forum search wasn’t unearthing a definitive “It’s almost always solved by replacing X,” I probably had some systematic troubleshooting in my future.

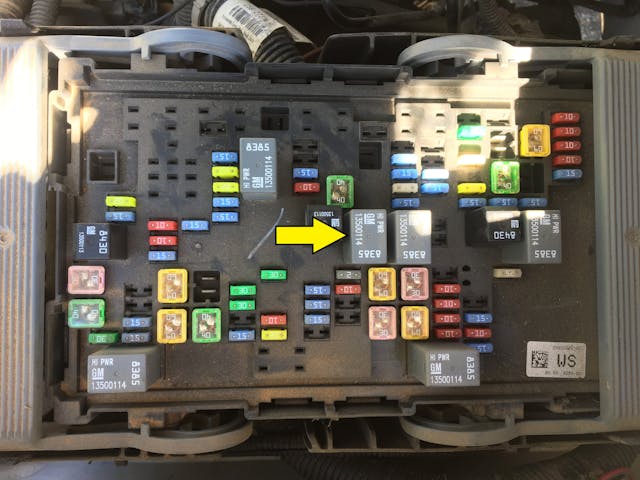

The test plan said that the P2510 code is due to the “relay responding incorrectly to the ECM command to de-energize.” As I described here, every relay is a little remote-controlled switch that has a low-current control side and a high-current load side. A relay not de-energizing is likely because the high-current side is sticking closed, or because one of the pins on the low-current side is staying energized and the other is staying grounded. I found the relay; the test plan was helpful in identifying the generic OBD-II code description of “ECM / PCM Power Relay” as meaning, on this truck, the relay labeled “PWR / TRN.” I pulled the relay out, tested continuity across the high-current side (pins 30 and 87), found them “normally open” as they should be, and verified that they closed when power and ground were applied to pins 86 and 85 respectively.

The step-by-step part of the test plan says:

- With the ignition ON, disconnect the PWR/TRN relay and observe with the scan tool for loss of communication. If the scan tool can still communicate with the vehicle, test the IGN 1 voltage circuit supplied by the ECM relay for a short to voltage. If the circuits test normal, replace the ECM.

- With the ignition OFF, probe the relay control circuit 19 X2 at the underhood electrical center [the fancy name for the fuse box] with a test lamp connected to battery voltage. If the test lamp illuminates test the relay control circuit for a short to ground. If the circuits test normal, replace the ECM.

- With the ignition ON, probe the relay control circuit 19 X2 at the underhood electrical center with a test lamp connected to a good ground.

- If the test lamp illuminates, repair the short to voltage.

- If the test lamp does not illuminate, replace the relay.

I went out to the truck to try these things, but I was stymied by the references to “relay control circuit 19 X2.” It wasn’t until later that I found that the test plan refers to a wiring diagram that has “19 X2” on it. It’s a pin on the ECM connector. When I traced it back on the diagram, I found that 19 X2 connects to relay terminal 86, which is the ground leg of the low-current control side. Why a test plan wouldn’t just say “relay terminal 86” which is right there in front of you—instead of forcing you to find it on a wiring diagram and then trace it back to the relay—is beyond me.

But I didn’t know this at the time, so I gave up. It was clear to me that to do anything more, the truck had to come home where I wouldn’t feel like I was running afoul of the “no work on cars in the lot” rule, and for that to happen, it needed to suffer the indignity of being the tow-ee rather than the tow-er. It was now Friday morning. I thought that I’d wait until the weekend when the place was likely to be empty to call AAA for the tow.

On Saturday morning, I drove to the lot on a reconnaissance mission to verify that it was a good time to arrange for the half-mile tow back to my house. To my surprise, the lot was 2/3 full of cars, and the other 1/3 was taken up by a cordoned-off area with chairs, a PA system, and people in formal attire who were dancing. The dance studio from which the parking space was rented was obviously having some sort of an event. The truck wouldn’t be moving today.

I went back early Sunday morning. The lot was empty of cars, but the cordoned-off area with the chairs was still there. I took the opportunity to do one more thing. I unlocked the truck, connected the batteries, plugged in the code reader, verified that the P2510 code was still there, then cleared it and tried to restart the truck. It still didn’t start, but the code didn’t repost. Hmmmm.

Then, while sitting in the truck, I did something else—I toggled the central locking on the key fob on and then off, then tried to start the truck again. I hadn’t been using the key fob to lock the truck, as a) I was in the habit of disconnecting the batteries and then manually locking the door, and b) I once had left the central locking on, and when I connected the batteries, the alarm went off. But whether it was coincidental or not, this time, the truck immediately started. I drove it straight home.

So, was the whole P2510 thing a red herring? Was it a code that had been sitting in the ECU for months and had nothing to do with the truck’s no-start? Was the root cause something to do with the anti-theft that simply needed to be toggled with the key fob? (It wasn’t as simple as accidentally hitting the lock on the key fob after I’d started the truck. I tried that and it didn’t recreate the problem.) There are many times when I say “don’t know, don’t care,” but here, the last thing I want is to be towing something with the truck and have it die, so I investigated further.

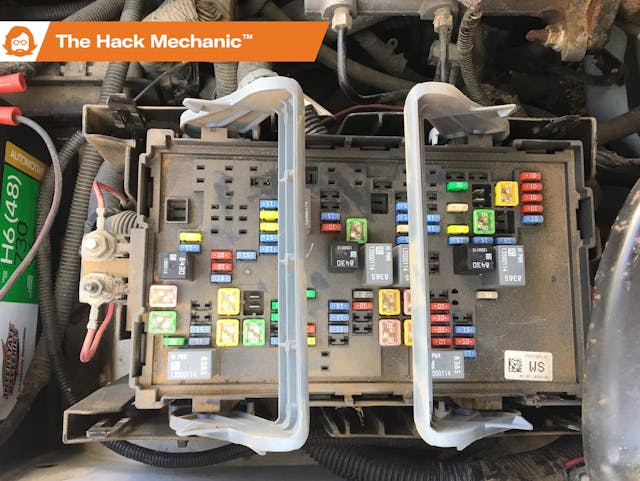

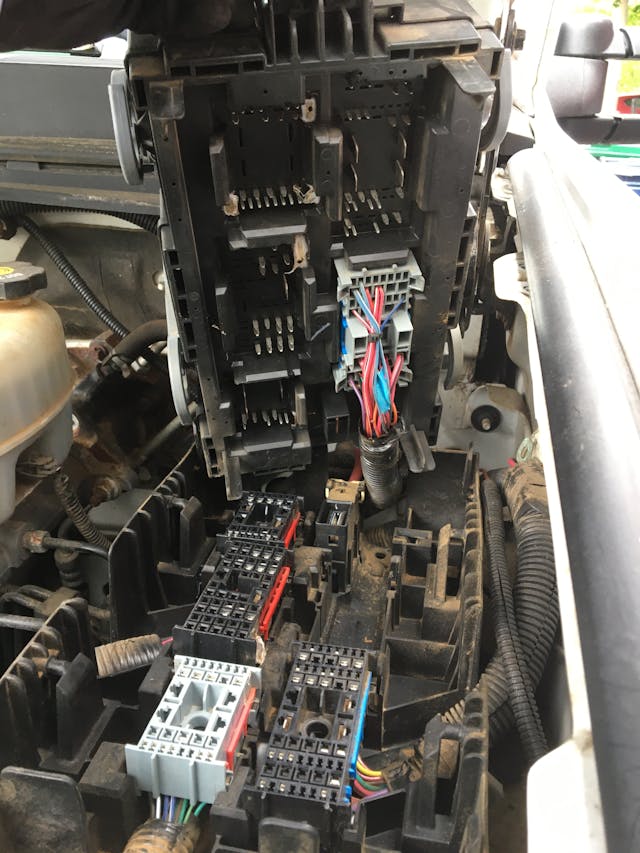

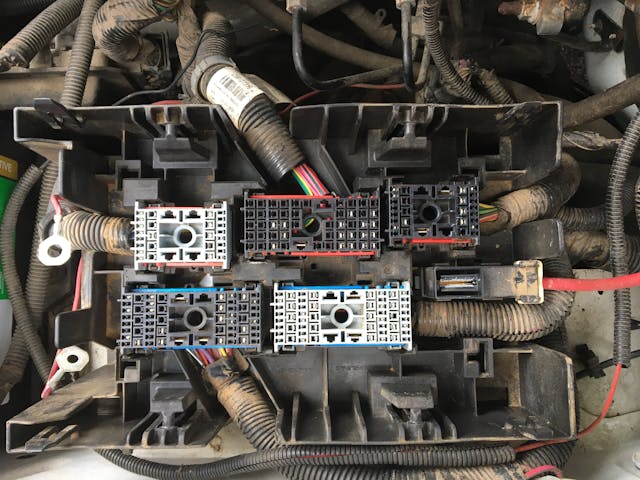

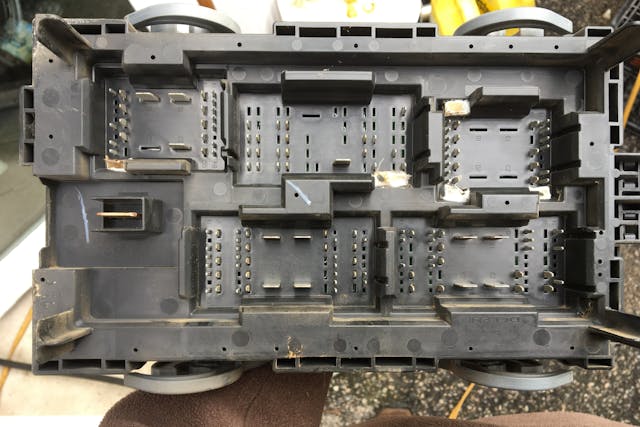

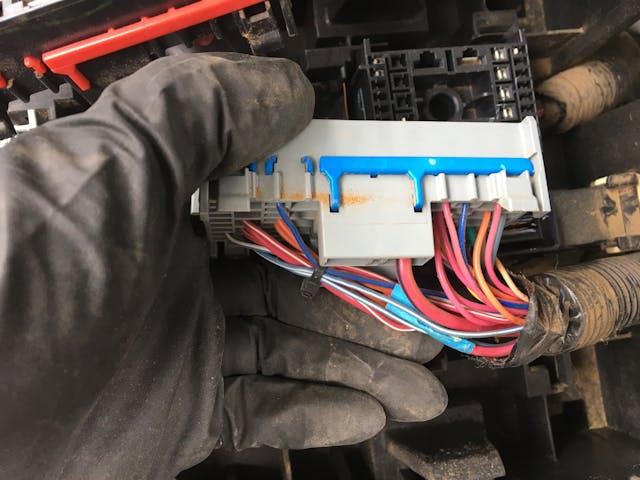

Because a number of posts pointed to the P2510 code and the no-start being caused by a corroded fuse box, and several folks reported that a new $220 fuse box solved their problem, I had a look. From the top, the fuse and relay sockets looked nothing like the fluffy-white-corroded or mouse-damaged examples I saw online, but the fuse box is easy enough to remove, as it’s just a plastic plate with integrated terminal blocks to which a series of big connectors plug into from the bottom.

Other than being a little dusty and seeing a few small moth cocoons inside, the underside of the fuse box looked fine to me, with no corrosion on the terminals.

Perhaps most important, I didn’t see any rodent-gnawing of the wires that led into the connector to which the PWR / TCM relay was plugged.

I put it all back together, started the truck, then tugged at all the sections of the wiring harness to see if I could recreate the problem. I could not make it die.

So, it’s a zombie truck. It died suddenly, it rose from the dead, and I don’t know why. But if it dies again, at least now I can make a better shot at going through the test plan. I’m trying not to be afraid of driving it. After all, there are still dump runs to be made, and Recaro seats to be snagged. And I need to ensure that the number of cars outpaces the number of sewing machines.

***

Rob Siegel’s latest book, The Best of the Hack MechanicTM: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem, is available on Amazon. His other seven books are available here, or you can order personally inscribed copies through his website, www.robsiegel.com.

Although I don’t have (nr intend to have) one of these trucks or anything with this motor in it, I read through the entire article with interest and did plenty of thinking about the issues and theories and tests – and I’m a self-professed “weenie” when it comes to electronics! This can only mean one thing: Rob is an excellent writer and knows how to rope in his readers!

By-the-way, I’d be really interested in some stories (ala the resident fighter-jet pilot) that include references to Rob’s prior career locating unexploded ordinance as well as car stuff. That seems to me to be a fascinating job… 😛

Thanks for another absorbing read, Rob, and I think your competition with Mrs. Rob is quite fitting, albeit probably a lost cause (Mrs. DUB6 is also a quilter, and I KNOW where you are gonna end up in this race).

Too much powering down from all the battery disconnects? I’m pretty shy about shutting down power on vehicles–my last was 2005 Denali–the AC system got deprogrammed when I put in my own battery.

Yeah newer stuff gets spooky with any battery outages from my limited experience (with newer stuff).

My bet is the security system. Toggling the door locks with the remote most likely corrected whatever “logic” keeps it from starting in the event someone breaks in. I’ve seen those systems do some strange things over the years… and fixing the problem usually involves closing the driver’s door and using the key to lock and unlock the door (or in your case, the key fob). I have saved many people the cost of a tow to the dealership by performing this simple task.

This is my guess as well. I was once the 4th owner in 8 years(!) of a Buick Enclave. If the weather was sunny and 65 or over, restarting in a parking lot between errands was impossible- wouldn’t even crank. We eventually found that disconnecting and then reconnecting the battery would reset whatever was running. I eventually traded it on something with fewer “ghosts in the machine!”

Huh. I remember – and long for – the days when a) a key unlocked the door, and then b) a key turn started the vehicle. And the reverse sequence turned the car off and locked the door. That’s it. That’s all there was to it. And it worked quite well as long as you had the correct key(s) to do those two things. Oh, you could get into a locked car and even start it without any keys at all, but if you did, you were likely committing a crime (not always, as I’ve done it to several of my own vehicles over time). But for the most part, the person with the key(s) was going to get the darned car or truck going and not have to be an electronic engineer, a YouTube user, or know the latest “hack” to be able to use their own vehicle. Trying hard to figure out why that wasn’t good enough… 😬

Rob, I’ve had some very interesting experiences with batteries in (relatively) new cars. I’m guessing three things are going on.

One is that modern vehicles will often exhibit more digital symptoms when dealing with lower than expected voltage. And by that I mean the car will work above a certain voltage, and the whole system will refuse to run below that. In an older car things are more analog, I’ve been able to start 90’s cars even when the battery is at 10 volts! They will misfire, cough, and sputter, so they give you a good warning that the battery is low before the no-start. That first start where the truck ran for 2 seconds probably dropped the battery voltage below the computer’s operating threshold before the alternator could bring the voltage back up and triggered the code. This is probably made worse by the fact that diesels take so much more current to start than gasoline cars, while their engine computers are just as picky.

Second is I’m very suspicious of the quality of new batteries. In my experience I’ve seen much more frequent internal mechanical battery failures – plates coming loose that will cause some extremely strange behavior. A plate can tip into another one and short, dropping the output voltage, then some additional wiggling or just temperature change can reset it’s position and it will be back to full voltage. This might be because many new batteries are manufactured overseas and shipped here. This leads to either poor quality manufacturing, and/or much more vibration loading in transit.

Third is battery terminals, they can sometimes build up high resistance, either through the cable misaligning on the taper of the terminal or corrosion. Cleaning them off with a wire brush can help tremendously with making sure you get full voltage at the computer. I’m guessing that removing the terminal and putting it back on helped to scrape the surface clean.

I’m not sure why toggling the door locks seemed to fix it; but I suspect the truck might have started on that second try if you had not toggled the door locks. If I were you, I would purchase a new high quality battery and either a solar trickle charger, or an inline battery shutoff switch, so you aren’t exposing the terminals to open air by leaving them disconnected. If you want to really kill the problem you could look into getting a dual battery setup, if the truck doesn’t already have one.

I’ve seen two other Chevy trucks from that era do the same thing. The first was an owner that didnt’ want to replace the worn batteries and kept jump starting. In both cases they would lock the door with the fob and unlock with the key whenever the batteries were dead and they charged or jump started the truck. We had a 95 Tahoe whose security system was also finicky about having its battery replaced, so I can’t say if its a GM design or unintentional effect.

And I love hearing about the truck. Not only the story of the awesome deal, but that it continues to see work for you. With the market today, that truck is probably worth 10x what you paid 🙂

Like many of our common devices, this truck needed a ‘reset’ with the fob to lock, unlock and then start. It’s all software, written by humans, so not perfect. My gas water heater used to get messed up after a power failure, so pull the plug, count to 30 and plug it back in. While I understand your loss of faith in the truck ( I drive a 53 year old E type), make sure you follow the procedure that brought success and keep your road assistance policy current.

I have cars that don’t get driven regularly on battery tenders, rather than disconnecting the battery. I have had issues with vehicles developing strange software related issues, without consistent battery power. This results in a trip to the dealer to have an ECM or other module “reflashed” to cure. Mercedes software is so cranky that most models have a main battery and another small one to maintain all of the codes if the main is dead or disconnected. With no diesel knowledge, your OBD code might be an ECM communication failure resulting in a trigger of the anti-theft (fuel cut-off?) I would consider a battery switcher / isolator and a solar charger for the truck? BTW, even with the custom air freshener issue, that is a sweet ride for as-needed use!