Frozen clutch or bad hydraulics?

My arrest-me-Signal-Red 1973 BMW E9 3.0CSi coupe is the unmistakable jewel in the crown of my not-a-collection. I never keep it in my rented more-humid-than-I’d-like storage—it’s always safe and sound in the garage at my house. In addition, I regard it as the best-sorted of any of my vintage cars. So when I needed to take it to BMW CCA Oktoberfest in Warwick, Rhode Island, a scant 70 miles south of my Boston-area home, I didn’t think twice about just checking the oil and the tires, reconnecting the battery, twisting the key, and driving it.

And when I did, the car lurched backwards. I’m lucky it didn’t crash into the back wall of the garage and incur tens of thousands of dollars of sheet metal damage.

I was so jarred by the event that it took me a moment to put the mechanics of it together. The shift lever was in reverse—I’d obviously left it there when I’d backed the car in—but I was certain that I’d stepped on the clutch. Or not? Regardless, the first thing I needed to do was shift it into neutral and try it again.

I couldn’t. The shift lever wouldn’t budge.

Hmmmmn.

The lever was so stuck in reverse that I began to think it might be a linkage issue, but I realized that, when coupled with the fact that the car lurched backward when I was sure I had my foot on the clutch, it was more likely that the clutch was the culprit. By applying an amount of brute force on the shift lever sufficient for me to worry about bending it or the linkage, I eventually popped it out of reverse and into neutral (in retrospect, I should’ve jacked up the back of the car to relieve the twist on the transmission likely being transmitted through the drivetrain). But when I tried rowing it engine-off-clutch-down through the gears, it took far more effort than usual.

I triple-checked that the gearbox was in neutral and I had the clutch pedal depressed (and the brake pedal too as insurance) and again started the car. As expected, it started without trying to take off anywhere, but with the engine running and the clutch depressed, I could not get it into any gear.

Clearly the clutch wasn’t working. But that can mean two very different things. It can mean that there’s a hydraulic or a mechanical failure. Or it can mean that the clutch disc is frozen between the flywheel and the clutch plate. And it’s surprisingly challenging to tell which it is.

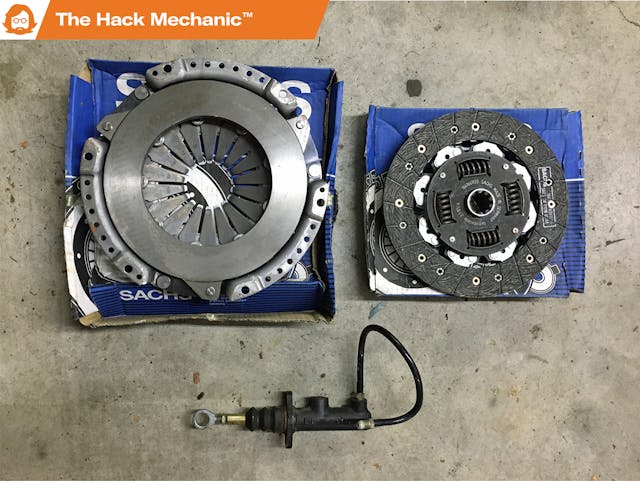

Let’s back up (smoothly; no lurching) and enroll in Hack Mechanic Clutch 101 for a moment. The clutches in most manual-transmission cars work in pretty much the same way. The clutch itself has two pieces—the clutch plate and the clutch disc. The disc has a two-sided sacrificial surface made from material that’s not unlike a brake pad or shoe. In the center it has a splined hole through which the transmission input shaft passes. The disc is held against the flywheel by the clutch plate, which like the flywheel has a machined metal surface. The clutch plate assembly is bolted to the flywheel, but when the sprung “fingers” on the back of the clutch are pressed inward, the machined plate surface retracts backward, freeing the disc (I know, it’s counterintuitive).

Separate from but intimately related to the clutch itself is the clutch release mechanism, which consists of the release lever, the sleeve, and the throwout bearing. The throwout bearing is what actually presses against the clutch plate’s fingers. It slides up and down on a cylindrical sleeve inside the transmission bell housing. It’s called a release “bearing” because since the clutch plate is bolted to the flywheel, it and its fingers are always spinning, so in order for something to depress those rotating fingers, it needs to touch them and then spin with them. The throwout bearing is moved fore and aft by the release lever, which may use a see-saw design or a simple forward-throw configuration.

Lastly is the linkage connecting the clutch pedal to the release lever. Although some old cars have purely mechanical clutch linkages, and others—like vintage Volkswagens, Porsches, and my Lotus Europa—have a cable-actuated clutch, most cars have a hydraulic clutch linkage, where a clutch master cylinder behind the pedal is connected to a clutch slave cylinder on or in the bell housing.

Now that we’ve identified the actors, we can start the play. When your foot is off the clutch pedal, the sprung pressure in the clutch plate causes the clutch disc to be sandwiched between the plate and the flywheel, making them essentially a single unit. So as the flywheel turns, the disc turns. The splined fit between the disc and the transmission input shaft causes the shaft to rotate, which in turn sends power to the wheels via whatever gear the transmission is in, or idles in neutral.

When you depress the clutch pedal, that moves a piston in the clutch master cylinder. Fluid under pressure is sent to the clutch slave cylinder, which causes a piston inside it to move, which moves a rod sticking out the end. This pushes the release lever, which in turn slides the throwout bearing along the sleeve. The throwout bearing contacts the fingers on the back of the spinning clutch plate. It presses against them, retracting the machined surface of the plate. This frees the clutch disc. With the disc no longer sandwiched against the flywheel, the spinning engine is no longer coupled to the transmission, allowing the gears to be shifted.

Got it? This concludes Clutch 101. But there will be homework.

A number of things can go wrong with all this. As I’ve written, failed clutch hydraulics are one of the “Big Seven” things that frequently strand a vintage car. A bad clutch slave or clutch master cylinder usually manifests itself as a pedal that goes all the way to the floor, usually accompanied by visible fluid leakage. However, sometimes there’s no leakage and the pedal stills feels fine, but there’s a problem building hydraulic pressure. Other non-hydraulic issues are that the throwout bearing can go bad, sounding like a little lathe inside the bell housing. Or the release mechanism itself can fail, either jamming the pedal or making it floppy, as were the respective cases on two separate occasions with my 1970 Triumph GT6+ 45 years ago—once when the sleeve broke and again when the pivot broke through the release lever (ah, the joy of cars built from recycled WWII metal). And, of course, eventually the clutch disc wears down, resulting in the clutch slipping when power is applied. The clutch can also chatter if it’s contaminated with oil from a leaking rear main engine seal.

But the other thing that can happen on a car that’s been sitting is that the clutch can stick. Just like brake pads and shoes will stick to the rotors and drums if a car isn’t driven, the clutch disc can stick to the flywheel and/or the clutch plate. The standard methods of freeing it are letting the engine run for a while to warm things up, then cranking the starter with the transmission in gear and your foot on the clutch and brake pedals. Or jacking up the back of the car, starting it in gear, revving it up, then having someone drop the jack. Or spraying brake cleaner into the timing inspection hole (at least on BMWs) to try to break the bond of corrosion. I read one very clever solution in an Alfa forum from a guy who had a spare transmission and clutch assembly and figured out exactly where to drill a quarter-inch hole to reach in with a thin screwdriver and tap the surfaces apart, but most of us can’t do that.

I had the “frozen clutch or bad hydraulics” thing happen when my 1972 BMW 2002tii “Louie” was part of an exhibit in the BMW CCA Foundation museum. As the exhibit was ending and I was planning to fly down to pick up the car, the museum staff told me that the car would no longer go into gear when running. As part of sorting out the car just a year prior, I’d replaced both the clutch master and slave cylinders, so my brain automatically checked the “well, it can’t be that” box and I thus assumed the problem must be a frozen clutch, but nonetheless I went down with spare hydraulics just in case. When I got there, the clutch pedal felt fine to me and I saw no evidence of fluid leaking, further reinforcing the diagnosis that the clutch must be stuck. I did everything you’re supposed to do to free it, but it remained stuck. Finally I jacked up the car, put it on stands, crawled under it, had someone depress the clutch pedal, and watched the action of the slave cylinder and the clutch release lever—which is possible because, as per the photo above, on a stock BMW 2002 four-speed gearbox, the release lever protrudes through the side of the bellhousing.

To my surprise, I found that, although the pedal felt just fine, the release lever moved a little, then retreated back, indicating a hydraulic pressure-loss issue. The video of this can be seen here. Was the clutch slave cylinder bad, or was it the master? I didn’t know, so I replaced the year-old slave cylinder first because that was easier. Unfortunately, that didn’t fix it, but replacing the year-old master cylinder did. The correct release lever action can be seen here.

Unfortunately, the transmission in my 3.0CSi is different from that on the 2002—the release lever is wholly contained inside the bellhousing, so you can’t watch it in action. The real lesson from Louie was that if you can’t actually see what the hydraulics are doing, there’s not really a way to tell bad hydraulics from a frozen clutch. You need to try and rule one out as best as you can, and then go down the road of the other and hope that you’re not wrong.

I’ve only had stuck clutches twice before. One was on my Z3 after it sat outside all winter. It freed up fairly easily after I started the car in gear with my feet on the brake and clutch pedals. The other was a long-dead 2002 I’d hauled home. For that one, I had to use the blast-brake-cleaner-down-the-timing-inspection-hole trick to let it seep between the clutch plate, disc, and flywheel and soften the bond of corrosion that had formed. And then start it in gear.

Now, my pampered 3.0CSi certainly hadn’t been sitting out in the elements all winter—it was in my garage and had last been driven just three or four months ago. But it had been a rainy summer, and my garage certainly isn’t a humidity-controlled environment. So I tried cranking the starter with my foot on the clutch and the brake pedal pinned but had no success. I was about to try spraying brake cleaner down the timing inspection hole, but to my amazement, I couldn’t find any in the garage (inconceivable!).

So I had a look at the hydraulics. I jacked up the car, set it on stands, crawled beneath it, and inspected things closely. I saw no sign of fluid leakage. Although there was no way to directly visualize the motion of the release lever, I unbolted the clutch slave from the side of the gearbox, roped one of my kids into service, and had him gently depress the clutch pedal while I pressed the slave cylinder’s rod against the side of the gearbox to simulate the push-back from the clutch’s sprung fingers. I couldn’t find a spec for exactly how far the rod should extend, but it moved about an inch and stayed out as long as the clutch was depressed. Hack Mechanic verdict: There was nothing obviously wrong with the clutch hydraulics.

In the morning, I reattached the slave and set the car back down on the ground. I was about to run out for brake cleaner but thought I’d give another try at cranking the starter. This time I did it with the car in third gear, foot on the clutch, and the brake pedal mashed so hard I thought I might break the back of the Recaro. Mercifully, the clutch broke free. So it was a stuck clutch.

But even though the problem was solved, I couldn’t let go of the idea that there must be some way of telling a frozen clutch from bad hydraulics. I asked the question of two friends of mine, both professional wrenches on vintage European cars. Both offered the same “if it quacks like a duck” diagnostic approaches I’d already followed.

So I thought about it quite a bit. I wondered if there’s a difference between the disc being frozen to the flywheel versus to the clutch plate versus to both. I don’t think there is. The clutch plate is bolted to the flywheel, so the two always rotate together. The disc is always coupled directly to the transmission input shaft via the splines. So whether it’s stuck to one machined surface or the other or both, I think the effect is the same.

Then I wondered if you should be able to feel a stuck clutch as lack of motion in the pedal. Intuitively you’d think you could, as we’re trained to make sure that, during installation, the clutch disc slides smoothly on the transmission input shaft’s splines. Hell, you even put a dab of special lube on the splines to make sure it does. So if the clutch is seized, shouldn’t you feel the disc not sliding?

Surprisingly, no. Once you’ve bench-pressed the transmission upward, positioned the input shaft in the hole in the clutch disc, aligned the two with the precision of lenses on an optical bench, rotated the flange on the back of the transmission to get the splines to mesh, uttered a foul streak of blue language that no matter what you do it’s not going in, prayed to whatever god you believe in, then finally slid the transmission forward and heard that reassuring THOCK that indicates it’s in place, the disc really doesn’t move much on the shaft other than floating slightly away from the flywheel when the clutch is depressed in the same way that brake pads move slightly off a rotor. It should also move slightly closer to the flywheel as the disc wears down. But more to the point, what you feel when you depress the clutch pedal isn’t the disc sliding on the splines—it’s the throwout bearing pushing the clutch fingers and moving the plate backward.

On a closely related note, I’ve heard of a malady where the clutch disc sticks not to the flywheel but to the splines on the transmission shaft. This causes the disc to drag against the flywheel, creating hard shifting until things warm up.

So, no, I don’t think there’s an easy definitive frozen-clutch-versus-hydraulics test. If it happens to you, I’d say do what I did and try to rule out the hydraulics. See if the clutch pedal feels normal. Check if the clutch reservoir has lost any fluid and if the hydraulics are leaking. If the release lever is visible, watch it while someone depresses the clutch pedal. If it’s not, pull out the slave and put the rod under pressure while someone pushes fluid into it. If it passes all those tests, it’s probably a seized clutch. So try to free it. If you can’t despite doing everything, you’re faced with either pulling the transmission to get direct evidence that it’s seized, or replacing the hydraulics even though there’s nothing obviously wrong. Which one do you want to try first? I thought so.

But if anyone knows of a secret test, I’d love to hear it.

And yes, from now on, I won’t simply mash the clutch pedal when I start a car—I’ll shift it to neutral and then mash the clutch pedal.

***

Rob’s latest book, The Best Of The Hack Mechanic™: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem is available on Amazon here. His other seven books are available here on Amazon, or you can order personally-inscribed copies from Rob’s website, www.robsiegel.com.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Another reason why simplicity – mechanical linkage, in this case – is best: no hydraulics, no hydraulic failure. Plus, hydraulics can leak internally, whereby they don’t function, though you tested that against the trans case. Yessir, clutch – and brake – material can grow something like fur and stick to its metal counterpart(s); the prevention for that is use and/or less humidity. And by all means, never start a stick car in gear, but in neutral. Some suggest not depressing the clutch pedal when starting, yet others prefer it; that’s a debate for another time.

My 95 z28 will not start unless the clutch is held to the floor, as a safety mechanism.

For repeat offenders sometimes a (window) cut into bottom of bell housing will allow access to the edge of clutch disc-pressure plate-flywheel interface. Thin tool worked along edge with clutch pedal held down can free things up. Sheet metal cover can seal up opening between events.

A clutch disc that is stuck ONLY to the pressure plate will still disconnect the engine from the transmission. The disc needs to be stuck at the splines, or its surface stuck to the flywheel, to keep the engine and transmission attached to one another.

A clutch disc stuck at the splines will still allow the pressure plate to move and therefore clutch pedal action will all feel normal. However the engine will not be disconnected from the transmission. Taking the car out of gear will disconnect the wheels from the rest of the bits, but the input shaft will still spin with the motor.

wdb, apologies if I got that wrong.

wdb, I stand to be corrected, but in every clutch I have seen the pressure plate does not rotate independently of the housing which is affixed to the flywheel, thus always rotating in concert with the flywheel. So if the friction disc is stuck to it, torque will be transmitted in the same way as if it is stuck to the flywheel. No?

once had a 220 SE benz that would refuse to engage the clutch after a stop. eventually found out that there was a check valve/orifice in the hose to the slave cylinder to control how fast the clutch released. if te orifice ws restricted the clutch would take minutes to release, a long time with people behind you honking and saluting LOL. a small drill bit cured that bit of German excellance in engineering.

Get the car to a long straight stretch of asphalt. Foot on the clutch. Start the car in first gear. On and off the throttle until the clutch breaks free.

I had a couple different clutch events. Sitting at a stoplight with the clutch pedal in my 260Z started to take off. Pupping the clutch pedal would get it to function. Had to rebuild the clutch master cylinder as fluid was “leaking by” the plunger in the master cylinder. I was doing some high (8000 rpm) shifts in my 1965 Mustang with a built 289 and when going into 3rd the clutch pedal went to the floor and stayed there, yet the clutch remained engaged. Had to get it home by killing the engine at stop signs and restarting the engine in 1st, shifting thru the gears without benefit of clutching. Pulling the transmission and bellhousing revealed the clutch plate had welded itself to the flywheel. Pried it off, put in new clutch, pressure plate, and resurfaced the flywheel. Oh, and lowered my shift point after that!

The joys of the manual transmission. We will miss them one day. Most folks go from manual to auto. I go the opposite. I was pulling thru the Krystal one day and a weld broke on the z bar/bell crank which ever you’d like to call it. I done the ole start in gear, got my sack full, floated the gears home, then welded it back up the next day. Dang I will miss the days of being so self reliant. Can you image a todays teen having to drive home with no clutch, if they can even drive a manual at all!?!

On my 912 Porsche the clutch cable didn’t break but the cable anchor point on the tunnel rusted and the pedal went right to the floor. Had to drive home about 120 miles and only had to stop once at the only traffic light in Breckinridge Colorado. Did a lot of clutch less shifting that night.

I have a dehumidifier in my garage so things don’t have a tendency to rust or give you that old bamp car smell. Depending on the weather, that thing can pull a lot of water out of the air.

Always start a manual in neutral with e brake on. Starting it in gear can risk these accidental lurching episodes.

Our 31 year old rarely used Toyota Pickup 5 on the floor would not go into gear. Tried your “instick the clutch” trick and shazam! It fixed it! We were thinking we’d have to have it towed to a garage and pay hundreds or more for a repair! Thanks so much for the great tip!

*UNstick!