Uncovering Canada’s forgotten WWII spy school

For generations, many of us have dreamed about having a licence to kill and the skill set to back it up. Before this description conjured MI6 agent 007 in the popular imagination, real-life agents learned the art and science of espionage during WWII at a top-secret spy school fifty kilometres east of Toronto.

Dubbed “Camp X” by locals, the paramilitary facility quickly became a hub for Allied communications and spy training in every field from assassination to intelligence. While serving in the British Naval Intelligence Division, Ian Fleming, the author of James Bond’s character, visited Camp X on multiple occasions. Though Fleming’s time in Canada certainly inspired elements of his series of British spy novels, the now-forgotten story of Camp X goes far deeper than movie trivia.

We Canadians don’t like to celebrate our history, but I’ve been fascinated by Camp X for years, an interest that is compounded by my enjoyment of Bond films. Plus, automobiles and gadgets are central to 007 lore, so it’s inevitable that when I order a martini, it’s shaken, not stirred. When the opportunity struck this year, I was obliged to explore the remains of Project J, as “Camp X” was originally known by the Canadian military, with a Bond-worthy set of wheels: the latest Vantage from Aston Martin.

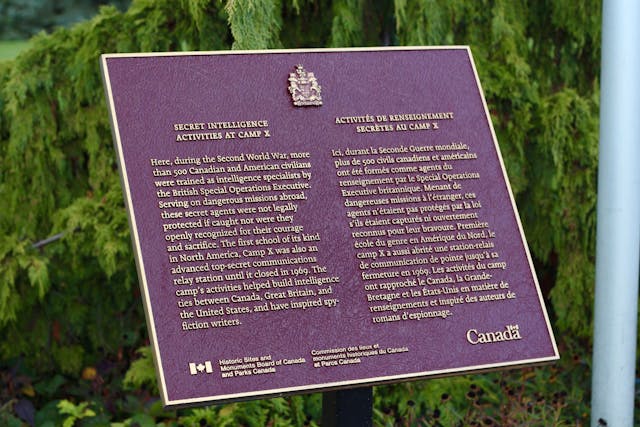

In the years following WWII, the spy school fell into disrepair and evidence of its existence was destroyed. Just 17 of the original 275 acres remain, serving as a memorial to the men and women who trained at Camp X. The area is now called Intrepid Park, honouring Sir William Stephenson, the Winnipeg-born World War I hero and successful businessman who established the school.

Before the United States entered WWII, Stephenson ran the British Security Co-Ordination office in Manhattan under the direction of Sir Winston Churchill. Codenamed Intrepid, Stephenson acted as a liaison between American and British interests at a time when the United States was not engaged in the war—at least, not officially. Stephenson was tasked with establishing a strategic location for what the British military called Special Training School No. 103, an innocuous name for an installation that would, among other things, train its students to become silent killers.

According to Lynn-Philip Hodgson, historian and author of Inside Camp X, Whitby’s Lake Ontario shore was chosen for several reasons. One key factor is that it was an excellent geographic location for Hydra, the Allied trans-Atlantic radio telecommunication system.

“That location was picked for the Hydra operations. It was ideal for the triple bounce across the Atlantic Ocean and [because of] the wide open spaces of Lake Ontario. With the camp elevated right on the shores of Lake Ontario, they could pick up the signals much more clearly than, let’s say, in Northern Ontario or somewhere else,” Hodgson says.

Another reason for situating Camp X in Whitby was that the state of New York is just thirty miles across the lake and a short drive from either Niagara Falls or Buffalo. Similarly, being near Toronto put Camp X near key segments of the Canadian population. This position was well-suited for recruiting: “You had a base of huge populations from the countries that were being occupied by the Nazis,” Hodgson says. “For example, France, Slovakia, Romania, Hungary, Italy, and so on.”

The trip from Toronto to the Lake Ontario shore in Whitby is a short drive along Highway 401 today, but Fleming would have taken the slow route along Highway 2. The freeways that crisscross our province weren’t even a dream in the ’40s.

On my way out of the city to Camp X, I drive by the site of the former St. James-Bond United Church in midtown Toronto. While Fleming is on record stating that he culled the James Bond name from an ornithologist and author, there’s another connection to Fleming’s fictional agent’s name. While on a visit to Camp X, there was no room for the British officer on-site and Fleming was forced to lodge with friends—directly across from St. James-Bond United Church on Avenue Road.

Hodgson admits that all of this may be true, bird-watcher connection or otherwise, and that Fleming likely made subliminal connections, too; while he was stationed at Camp X, he would pass by St. James-Bond United Church twice daily.

The Vantage makes the trip from the city out to Whitby an occasion and the Diavolo Red paint on the athletic lines of this Aston draws unnecessary attention. This grand tourer isn’t very discreet, but it is a comfortable and quick machine. Exiting the freeway, I send the Vantage down Thickson Road and over to Boundary Road for the quick drive to the Lake Ontario shore and Intrepid Park.

Aston Martin finishes these Vantages in a way that’s true to the ethos of a grand tourer, with a responsive and compliant chassis setup paired with an engine dominated by its broad torque curve. The result is a traditional British blend of relaxed and rapid motoring. Unlike, I imagine, the spies who trained there, I’m not shy about letting the exhaust of the Vantage burble and pop on the way down to Camp X.

Intrepid Park lies on the border between the cities of Whitby and Oshawa. It’s surrounded by a public-use, lakeside park and industry to the north. It’s a stone’s throw from General Motors’ former Oshawa assembly plant, which is no coincidence. No buildings remain on the site, but the memorial commemorates the cooperation between the British, American, and Canadian forces in the endeavour.

Hodgson reminded me of the permanent collection of Camp X artifacts at the Region of Durham headquarters, a few kilometres northwest of the original facility. I recall viewing the relics years ago while awaiting yet another trial for speeding near Canadian Tire Motorsport Park, also located in Durham Region. At the time of this writing, the building is only open to essential business under COVID-19 pandemic rules, but I hope it will reopen soon—that collection was impressive.

In lieu of an archive visit, I point the Aston north up Thickson Road toward all the last remaining building of Camp X. Years ago, a portion of a dormitory was saved and moved to Whitby Animal Services, a good ten kilometres from the site. The modest-looking dorm sits behind the main office, entirely uncelebrated; efforts to move it to a permanent home that would recognize the significance that the structure played in WWII have been unsuccessful.

Hodgson tells me that Stephenson, to avoid a paper trail, paid Camp X staffers out of his own pocket. “Being a very wealthy man prepared to do things that way, he would have his secretary prepare a little pouch with the amount that each person made and distribute [them] to the employees,” Hodgson says. “It was a very simple, simple operation, but Stephenson was prepared and would rather have had a method of paying cash and avoiding any kind of a paper trail or record.”

While we can casually celebrate the successes of Camp X today, the spies there fought a real war in the ’40, as Hodgson reminds me. They had no guarantee of success—and certainly no assurance of safety. “They would have gun training, explosives training with plastic explosives, how to survive, how to use a compass with a map, what to do if they get captured by the Gestapo,” Hodgson says.

“That was probably the hardest part of the training because, as one agent told me, they beat him up to within an inch of his life. He said he was so happy when he was captured by the Gestapo because he said there wasn’t anything that he wasn’t already expecting, which is a big part of surviving the psychological part of capture,” Hodgson says.

Most of the files from Camp X have been destroyed, lost, or will never be recovered. Countless agents died during operations during the war, so there are few recorded successes from its graduates; even after death, their names and achievements are cloaked in anonymity.

Hodgson recalls the Yugoslavians who immigrated to Toronto and were recruited into Camp X: “They were very successful because they would be dropped in behind enemy lines to get very close to the mountains where Tito had his army. Tito’s people would pick them up immediately. They dropped caches of armaments with them and then the agents would train those people on how to how to sabotage things. They were very successful.”

“The other group were the French-Canadians,” Hodgson says, “because it just so happened that they were ramping up to the D-Day invasion and the French Canadians played a big role in that particular event.” Because they assimilated easily in France, French-Canadian spies recruited network of resistance fighters who paralyzed German military traffic by executing 950 rail line demolitions out of a planned 1000, as requested by Allied command in time for D-Day.

Fleming when on to fame as the author of the James Bond series, but Special Training School No. 103 also hosted wartime operatives whose names may be familiar to some. Paul Dehn trained spies while at Camp X then later wrote the screenplay for Goldfinger. Prolific children’s author Roald Dahl was also a guest, following his survival of a plane crash in Egypt and subsequent reassignment to British intelligence under Stephenson. Even noted advertising man David Ogilvy is said to have been schooled at Camp X.

Fleming was no mere interloper from the big city office: he trained with his unit in Whitby, according to Hodgson. “He was there many times. In the summer of 1943, he was there with his unit of thirty-eight men and they were there for what we would call today modern-day [Navy] Seal training,” Hodgson says. “Their operation at Camp X was simply training in Lake Ontario. They would practice over and over again putting their mines on the underwater hull of a ship.” Very Bond, if you ask me.

At Camp X, men and women were trained in the most advanced espionage tactics of the time, and many were simply sent off to their deaths. Only a few made an appearance in the footnotes of WWII history, but these courageous men and women must be remembered as heroes that helped secure the freedoms we enjoy today.

Wheeling the Vantage back from Camp X gives me time to consider the sacrifices these people made, at a time when their future was uncertain at best, but it’s unfathomable to me. It’s part of the poignancy of history that a fictional character spun from the mind of one of the camp’s attendees is more familiar to us today than the school’s attendees. I can’t begin to imagine what Fleming would think about today’s Aston Martins, either; but I suspect he’d first equip them with the latest high-tech weaponry from Q Branch. For me, I’m sufficiently humbled by the day’s sightseeing to quietly pedal this British grand tourer back to the city.