Smithology: The Captain and Me

The tool spoke to me. A quiet voice, on the back of a shelf. So I knelt down and picked it up.

We were in Michigan. My father has a small cabin in the state’s rural northern half. Several years ago, when the Shell station in the nearest village went out of business, a local told me it was because the “town just wasn’t big enough.” In high school, I spent two summers working at a nearby boatyard, running errands and sanding down old Chris-Crafts under restoration. Twenty years on, I remember little from those months save the reek of Interlux spar varnish and where the tools are in the local hardware store.

Last month, my wife and I drove up to that cabin for a short vacation. For one reason or another, I hadn’t seen the hardware store in a few years, so I wandered over.

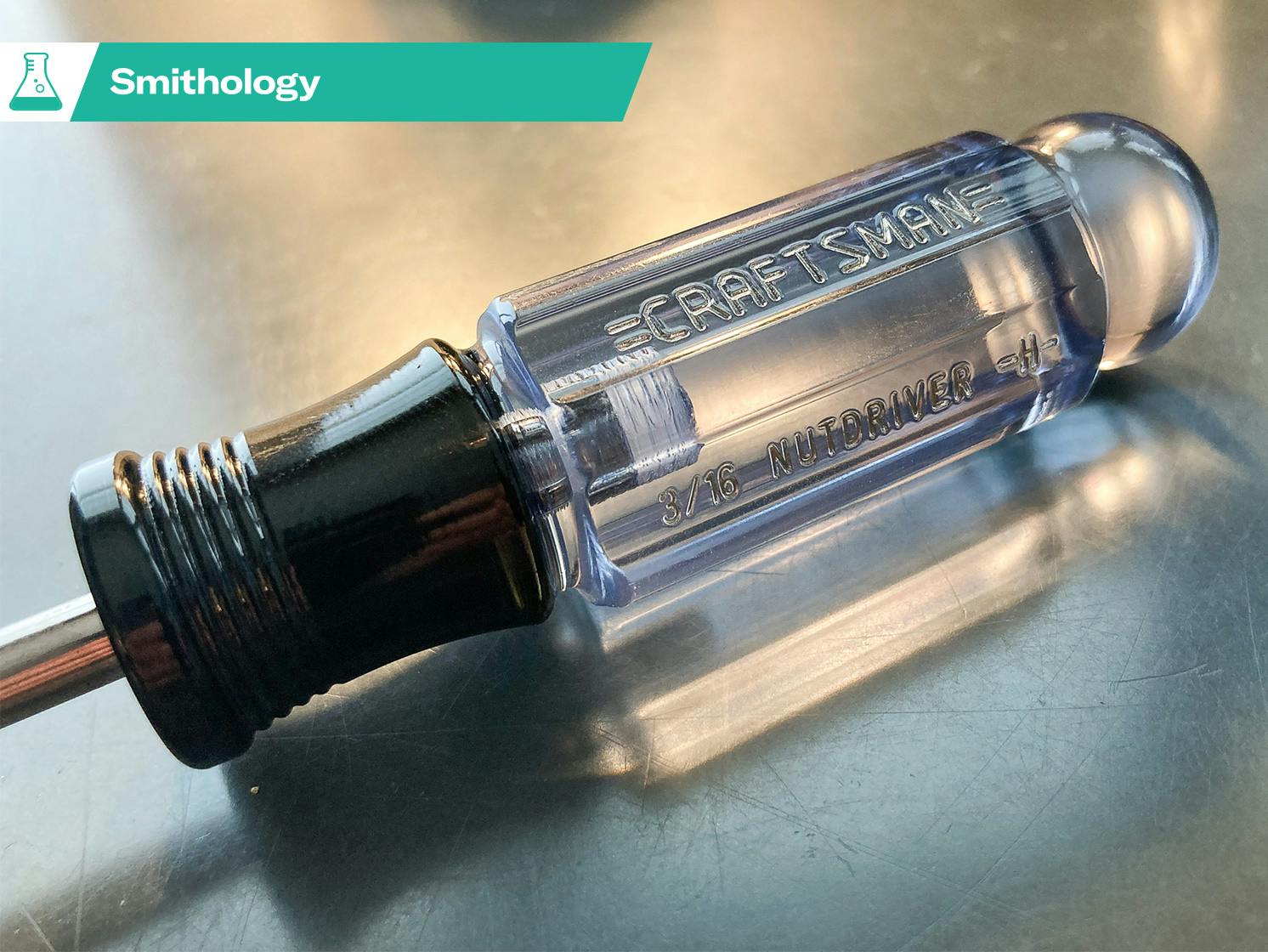

Inside the store, I turned the tool over in my hand. The dust-covered tag read MADE IN USA, bold letters. To the right, FOREVER FULL WARRANTY.

I looked back at the shelf. Racks and hangers of hand tools. The others were similar at a glance but undeniably different: sloppier molds and plating, brighter and tackier colors.

A leftover.

The voice spoke up again. Childlike, if children happened to be manufactured with toxic plating compounds.

“Where am I?”

I took a look around. No one else in the aisle. “Uh… hello?”

“Where?”

One of the side effects of going through a long year, and then a long year after that, is that you eventually reach a point where you’ll talk to anyone about anything. Often aloud.

“A hardware store?” I said. “In northern Michigan?”

“What is a northern Michigan?”

“A large part of the upper Midwest, but I feel like that’s not important right now.”

“What is important?”

“You’re a 3/16ths nut driver. I am a people.”

“Oh. What are we doing?”

“Either I’m losing my mind, or we’re having a chat near the fish hooks in broad daylight.”

“Neat!”

I turned the driver over in my hand. On the back of the tag, the words Sears, Roebuck, and Co., Hoffman Estates, IL.

Five dollars says you own Craftsman hand tools or know someone who does. Sears stores once dotted the country, their tools a kind of everyman commodity: American-made, low-priced without feeling cheap, durable but not too heavy, a nutty lifetime warranty. Those tools would soak up long volumes of hell, and when you inevitably broke one while doing something stupid, any of those stores would take it back and hand over a replacement, free.

Nearly 20 years ago, I found a rusty chrome ratchet extension in the paddock grass at Putnam Park. The end was cracked in half, blown apart with an impact gun. A week later, I walked into the Sears near my parents’ house in Kentucky and set the extension on the counter.

The sales guy was sitting with his feet on a shelf, paging through a catalog. Barely looked up. “Exchange box is over there,” he pointed. “Aisle’s in the back.”

“I didn’t buy this. Somebody else blew it up.”

He pointed at the box again, unimpressed. “Don’t matter. In the box.”

Many people have similar stories, because many people once went to Sears. Those stores came in several sizes, selling everything from clothing to tires, but even the small ones had a deep stash of car-specific tools and associated whatnot. The variety was half the draw. You’d walk in and give the clerk some 3/4-drive universal that had sheared apart during bonehead abuse, and then you’d stroll toward the socket aisle, past the dwell meters and muffler-bearing adjusticators, only to realize along the way that you urgently needed another timing-light inductor to replace the one you melted on a manifold six months ago. Jeweler’s picks over here and EZ-outs over there and Can’t remember which Allen bit I left at Road America, might as well buy the whole set.

Shortly after that, you walked out the door grasping items you would doubtless own forever, small money spent for what seemed like large victory, and you were happy.

Sears, Roebuck was founded in 1893. The Craftsman name was trademarked in 1927. Nine decades later, after the firm had declared bankruptcy and descended to store closures and a holding company, Stanley Black & Decker bought the tool line for $900 million. Craftsman stuff is now sold in certain hardware and home stores. A few of the old Sears suppliers stuck around, but the product rarely shows it. Somewhere in that late decline, the tool designs were noticeably cost-cut and resourced offshore. (For its part, SB&D claims to be working on that last bit.)

“Wait,” said the nut driver, thoughtlessly interrupting a fine inner monologue on the long fall of quality American retail.

“Yes?”

“Am I the cost-cut garbage?”

“Nah. Last of the good. Never found a home.”

“This Sears … it must have been wonderful.”

“More like ordinary, but that was kind of the point?”

“Huh?”

“The tools were just a part. There were also washing machines and vacuums and discount jeans.”

“You bought pants there.”

“Not me.”

“A vacuum?”

“Once, I think?”

“Mostly just things like me?”

“Pretty much.”

Great American-made tool brands still exist. For that matter, you can still buy vintage Craftsman bits online. But each of those options can get shockingly expensive, and they aren’t the same as getting exactly what you need, on a moment’s notice, without feeling like you either paid too much or settled for disposable chintz. The closest old-Craftsman analogue, at least in terms of store count and car focus, is now Harbor Freight: visibly cheap but affordable tools, sold across America but made elsewhere, that work fine for long enough, except when they don’t.

“I feel old,” said the nut driver, sighing. “With dead parents.”

“That fall always seemed like a choice, you know? Sears used to be forward-thinking. When malls grew into a threat, they built their own malls. They founded a credit-card brand before everyone was doing it. Then the internet happened and somebody reached the limits of their imagination.”

I set the nut driver back on the rack. Then I spent far too long sifting through ratchets and screwdrivers, looking for old among the new. Only a handful of leftovers remained, and in odd sizes. The newer wrenches were particularly off-putting, the same at a glance but cheesier in plating. Heavier, too, with more grain in the finish. A shopworn claw hammer looked the part, its rubber handle cracked and powdery, but the sticker on the back said it was made only last year. Just falling apart.

Nostalgia can be insidious. Use it wrong, you grow convinced that yesterday is the only possible peak. Which means existence must be getting worse every day, and at that point, why bother getting out of bed at all? The world is generally improving, of course. But not in every way at once; it gets better in fits and starts and in different segments across the spectrum of human endeavor. And sometimes, for reasons that have nothing to do with the advances, it stalls or goes backward for a while.

I felt a weight in my palm and looked down—the driver was back in my hand. Must have picked it up without thinking.

“Hi!” it said.

“Just thinking,” I said.

“About what?”

“The occasionally tangible yet perpetually transient nature of societal evolution vis-a-vis emotional steepage.”

“Deep thoughts for a hardware store.”

I found myself wondering if clinical insanity is something you see coming. “We all get therapy somewhere, I guess?”

“I would like to go home with you.”

“You aren’t free, and I don’t meet many 3/16th nuts.”

“You have no idea how often I hear that.”

A life around metric cars, and I can’t tell you the last time I touched a 3/16th fastener. More to the point, nut drivers as a breed are an acquired taste. Awkward, clunky little things.

I stood there for a moment, feeling strangely guilty. Then I remembered the old joke about old people: If a new object or idea met the world before you were born, you accept it as part of the way things are. Anything new from birth to age 40 is up for debate, evaluated on merit. And anything invented after you reach middle age is inhuman devolution that must be killed with fire.

My shop box is a mix. A few family hand-me-downs, but mostly bought on my own. Blue Point, SK, Snap-on, Beta. Plus a glut of old Craftsman.

I have, over the seasons, purchased an obnoxious amount of stuff online. Still, there’s something about walking into a store and being happily surprised by a shelf.

A second later, I was grabbing a few cleaning supplies and doodads that I needed but also didn’t need at all, and then I was walking to the front of the store, and then I was placing a dusty nut driver on a counter next to a credit-card reader and wondering what it feels like to adopt an orphan.

Seven dollars and forty-nine cents. On the back of that tag, the words If any Craftsman hand tool ever fails…

Everyone has a warranty these days. Can’t tell you why that one meant something.

My friend Zach Bowman owns a much-abused screwdriver named Mr. Bendy. He uses it for all the non-screw jobs for which screwdrivers are prime, the stuff screwdriver manufacturers specifically ask you not to do. I enjoy Mr. Bendy, and stupid names are fun. My new friend is now Captain Useless. Maybe he parties like Mr. Bendy and finds work outside his design brief. Maybe he sits in a drawer for years. Doesn’t matter. Nobody buys emotionally charged objects in a blinding flash of logic. Some things enter your life simply to remind you of why they entered your life. And inanimate tools without pulse or brain do not talk to you, ever.

Unless, of course, you’re meeting unexpected memory and delight in a quiet aisle in the far reaches of the great upper Midwest. And, more than anything, willing to listen.

I bought my first Craftsman “rollaway” tool cart and top at 15 years old with very dear money. Gray boxes, red drawers. (You remember). I filled it almost exclusively with Craftsman tools.

I now own 6 floor to ceiling Craftsman boxes, still full of good-working, mostly Craftsman tools. The little gray box just wasn’t big enough and I couldn’t get those 3 drawer inserts in the same gray/red combo. I’m 69 now. Last year I gave the gray box and top to a neighbor kid who likes tools. It’s still going strong.

You are a good man Sir!