Smithology: If you’re a vampire, or maybe a rock

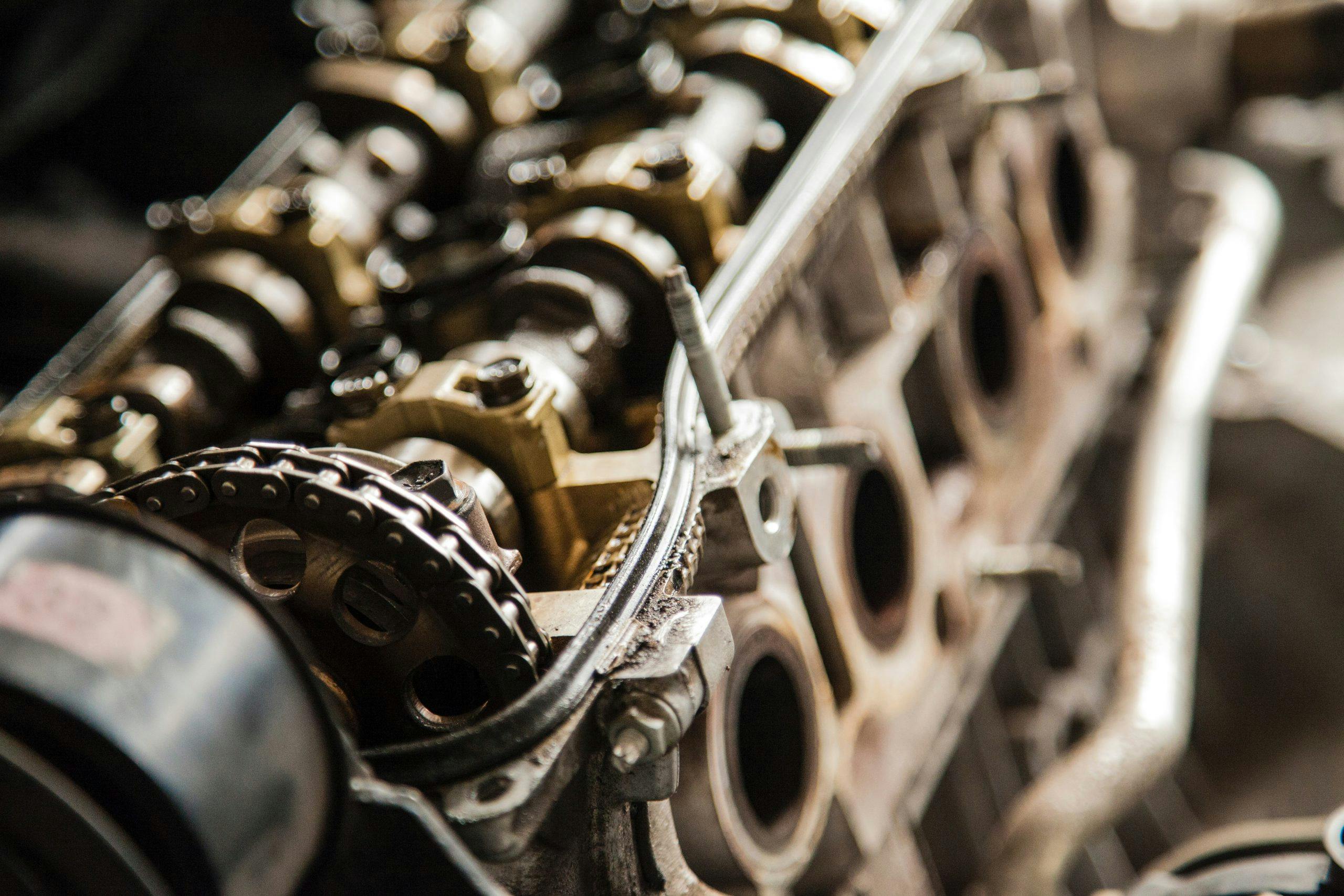

There’s a new engine in the house.

I knew this was coming. I sold the truck a few weeks ago. Its tidy little Chevy 350 went away, motored its big round air-filter housing off to a good home. I drove that truck every day, so when it went, on grounds of practicality—two kids plus a single cab shortbed will do that to you—I bought something to fill its place. As you do.

The man who bought it owns a farm in Kentucky. A Chevy, off to do farm work. This makes me happy, even as I lose what felt like a friend. No more stone-age throttle-body injection, no more amusingly high idle on cold start—Hi guys, cold oil! Listen to me churn that stuff around!—no more opening the hood every so often and looking at the water pump I replaced more than a year ago, before I ran that engine from Seattle to Tennessee during a cross-country move. I installed and know that radiator, that belt, that alternator. Not to mention some of those vacuum lines, all eight of those spark plugs, the clutch and brake master cylinders, the clutch slave, the clutch disc and pressure plate and release arm, the rotors, the shocks, the trans mount, those fluids, the driver’s door latch. I can close my eyes and remember what it felt like to throw the old, worn-out parts in the trash.

You buy a machine, you want to take care of it. Then it goes away at some point, and you forget, almost immediately, all the work you did. Or at least I do. I occasionally sit and wonder what happened to a certain Japanese four-cylinder motorcycle that I owned years ago. I pulled and rebuilt the head, then pulled the block and tore it down. A winter of my life, and the thing looked like new inside. Does the person who owns it now know or care? Of course not.

I liked the 350 in that Chevy. Its replacement, currently sitting in my driveway, is equally likable, just different. Smaller, for one. Not a V-8. Different country of origin. Another flavor of machine, another approach to valves and rotating masses and the thousand problems of which any engine designer is heir to. How many answers are there? Does anyone ever stop to think about how remarkable it is that most of those answers are just small evolutions from other, older answers?

Did you know that we can trace many fundamentals of modern engine design back to a group of Peugeot employees from the early 20th century? They were known as Les Charlatans. Crucial among them was a Swiss draftsman and engineer named Ernest Henry. Most of his work took place before World War I, and he died in 1950, near Paris, all but unsung. Yet his efforts helped lay out the twin-cam, four-valve powerplant and thus either directly compassed or influenced a whole century of automotive engineering. If not for Monsieur Henry, there would be no Ettore Bugatti, no Harry Miller, no Gioacchino Colombo, no Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche being spoken of reverently on Instagram by a host of people who think car enthusiasm begins and ends in Stuttgart. Or at least, we would not have the work of those people as we know it today. A hundred years of evolution, and an entire industry is still in many ways listening to the ideas of a long-dead Switzer. Elvis fell off the map quicker.

Humbling stuff, at least for me. Elon Musk is probably not humbled by Ernest Henry, but then, what is Elon Musk humbled by, anyway? I type for a living and am known for directly compassing little more than my own pants. I am humbled.

A new engine in the house. The car it powers is not special. It is so ordinary that I won’t even bother to list its make and model, though some of you will find me and ask, because people tend to email or DM me with questions on all sorts of things, and in that case I will tell you, but you will probably be disappointed, so this is me, here now, telling you not to ask. Just imagine something moderately entertaining and possessed of a clutch pedal and a lovely little marvel of a powerplant, and everyone will come away happy.

Most of the specifics are irrelevant. The car was made in Europe. A lump of aluminum and steel, built an ocean and a continent away, 190,000 miles and 16 years ago.

Sixteen years is a long time. When I was 16 I was very stupid about many things, but I knew at least some small part of what I know now—namely that I am drawn to anything with internals too complex to understand at a glance. That description works for so many wonderful things—A woman! A locomotive! The Space Shuttle! But mostly, it means that I love cars and motorcycles, and that I know a bit about both. And that this knowledge makes me want to know more.

The car around the engine is newish, at least compared to my modest fleet. (Quick inventory: Four running automobiles, one running old motorcycle, one temporarily non-running old motorcycle, and one engineless shell of a 1960s German four-door sedan.) The newish car holds side-curtain airbags and heated seats, but that isn’t saying much; these days, if a car is really and genuinely new, it likely holds multiple screens and more than 12 volts, and possibly maybe kinda sorta not even an engine, Good lord, kid, those are going away, everything now is liquid-cooled battery skateboards and a rock-star CEO who says we’re going to be profitable in just a few short decades have you bought the stock? You should probably buy the stock please buy the stock.

So many EVs are engaging machines, genuinely interesting. Fun to operate and learn about.

But there is still something about an engine.

I will turn 40 in two months. I am not a new person, though I occasionally feel about five years old when it comes to things like the candy aisle at the local gas station or the work of Hayao Miyazaki. Forty is not young unless you are a vampire or a rock. The sole offset is the knowledge that comes with age: The older I get, the more aware I become of how my process works. I am, for example, both infatuated with the new and drawn to the old, but only inasmuch as there are stories under the surface, ideas that make the material object relevant and interesting.

A lot of people seem to believe that loving the old and the new at the same time is mutually exclusive, especially with machinery. If you ask me, those people are possibly less than curious and perhaps just need to stop doomscrolling for five minutes and go read a book. If there is a single and central problem with this world, it is our natural inclination to box everything into black or white. Gray areas are perpetually unfashionable and rarely tied to easy answers. Hot takes must always be inflammatory. Dunning-Kruger poster children head up companies, say “it’s not that hard” about complex and nuanced tasks while simultaneously doing subpar work, get rich and famous in the process. Shouting dictates the discourse, because who can be heard over shouting? You think on it enough, you can want to run out the front door and far away.

But there is a new engine in the house.

Even that first oil change gives little moments of grin: The sump gasket isn’t leaking! Amusing gunk lies under the oil cap, but not so much as to be concerning. The filter cover was not overtightened by the last wrenching goon, but he did install some cheap Chinese aftermarket filter that barely fits and appears to have eaten half its pleats. Thoughts pop up while pulling the drain plug: How does an engine get this far without a weeping rear-main seal? The floors are not rusty, but the subframes could be cleaner. (The car came from Chicago. Go figure.)

I have questions. There is a transfer case behind that engine, and it occasionally clunks in the parking lot. The tach needle wavers at idle. Not an actual misfire, and barely perceptible—just a twitch, but odd. Gunk inside the instrument cluster? A lazy ground somewhere? Too much resistance in the muffler bearings? Who cares, really? It works for now. You fix things when they break, except when preempting the inevitable. A wiggly tach is neither critical nor a sign of eventual doom. Good to know, though.

The car isn’t fast, but it sounds nice. Redline is smoother than idle, almost creamy. I have owned one of these engines before, same manufacturer and design. The other one was more powerful, with a longer stroke and greater displacement. Many things feel the same, with this one, but it makes no difference. New is new.

I didn’t expect to like it this much. That’s part of the charm, isn’t it? Countless unknowables and miles to go, and you can kid yourself into thinking you know what you’re getting into.

Sometimes you do know. Most of the time, however, there are surprises. Miles pile on. If you’re like me, you revel in the finding out. After a while, the thing starts to feel old to you, possibly even as old as it is. You get to know all the nooks and crannies, know or remember why everything works as it does. You remember this repair job and that one, how that bolt came this close to shearing. You think occasionally, while sitting at work or in the dentist’s chair, how it feels to grab fourth gear from third at full throttle, just a brush on the clutch and the car keeps going, almost as if you had never lifted. After enough time, you know that feeling the same way you know which foot fits better in your favorite pair of sneakers.

But those first few moments, give or take, there’s nothing but possibility. No answers. Just time ahead.

There’s a new engine in the house.

And we are stoked.