Smithology: GTO, Boss at eight grand, the word lost in the wind

“People will say to me, ‘How can you make so much of a song?’ … I’ve heard that all my life. It always means the same thing: Stop thinking.” — Greil Marcus

You are what you love, as Jenny Lewis sang, and not what loves you back. Related: When someone calls and offers to let you meet a Ferrari 250 GTO, you stare at the nearest wall while thinking smoochy thoughts of V-12 howl and trying to blink your eyes clear out of your head.

A GTO is inanimate. It cannot love you back.

Not that you don’t ponder those dozen pistons at full rip and try to argue the point.

Thank Jeff O’Neill for all this. O’Neill, 64, is a vintner from Northern California. His gray hair seems perpetually ruffled, and his eyes go bright in a paddock. A while back, he noticed that something had shifted in vintage racing: Years of steep appreciation had made a certain kind of historic race car bonzo expensive, even by the standards of the realm, and as a result, those cars were disappearing from public view, replaced by clones and tributes or nothing at all. A pastime built on the sharing of big history was beginning to lose the “big” part.

O’Neill is a vintage racer himself. He began griping to friends: People deserve to experience this stuff, see it run, we have a responsibility to not sock it away. How machines with rich pasts are basically living stories, and if you don’t share those stories, they get forgotten.

A pal told O’Neill to stop harping and do something, so he did. An event was founded. Former Monterey Historics impresario Steve Earle was drafted to help coax out potent cars rarely seen in daylight. Things like GTOs and Porsche 917s signed on, plus a raft of hyper-rare sports cars and prototypes, drawn by a promise of close but respectful racing, no jerks allowed. Mercedes-AMG agreed to send a Formula 1 demo team and have development driver Esteban Gutiérrez aim an old Lewis Hamilton car at the lap record. The paddock was planned around spectators, with a kids area and wine tasting. Race cars were hosted in group-hug tents, like at Goodwood, family-style and shoulder-to-shoulder.

The sum of that planning went down at Sears Point in Spring of 2019. O’Neill called it the Sonoma Speed Festival. Spectators loved it. That HAM tub blew the lap record to pieces. The whole thing felt special.

“You want to see the cars, smell them, hear them,” O’Neill told me. “A museum doesn’t bring them alive. I wanted to be absolutely firm on authentic history in a way that nobody’s doing in the world.”

Our man is now in round two. His sequel, dubbed Velocity Invitational, kicks off at Laguna Seca on November 11th. When O’Neill asked his PR team for promotional ideas, one wag suggested renting a track and handing a few cars to journalists with race experience. Stick the writers in the stories, someone said, let them drive and slide around. Plus, hey, you know a guy with a GTO, maybe light that candle and give some rides.

O’Neill said no to the journalist drives (“I thought it was insane”), then changed his mind. When we met at California’s Thunderhill Raceway Park this September, I asked him why.

A corner of his mouth turned up. “You know what? They’re just cars. It’s their jobs to be here.”

Walk the talk. Good man.

Thunderhill is fast and sweeping, draped over grassy foothills near the Mendocino National Forest. There were five guest drivers, all writers or YouTubers, your narrator included. Other than that, the track was basically empty. I put on my helmet and climbed behind the wheel of one A-lister after another. Instructions were few: The Alfa GTA Junior thrives on throttle. Shift the Boss 302 Trans-Am car (ex-Parnelli Jones, ex-George Follmer, 1969) at eight grand. The sliding-window Mini Cooper S will spit loose in a heartbeat if you lift in a corner, so don’t do that unless you like fun and things that are good.

A gaggle of other Velocity cars were present for unrelated testing. In idle moments, I counted tubes on a Maserati Birdcage and mooned over two 2016 Ford GTs that ran at Le Mans. And there was, of course, that GTO: chassis 4757, a ’62 owned by Bay Area dealer magnate Tom Price. It has been raced more than 300 times. O’Neill drives the car in events as a favor to Price, which makes the latter sound like a laid-back dude of killer taste and now I want to meet them both and buy all the drinks.

How happy a dance is relativity. Each guest got 15 minutes, give or take, in Alfa, Boss, and Mini. I drove a thundering Ford from the original Trans-Am and watched its small-block try to twist the tach off the dash. The GTA flung through fast sweepers, aluminum roof a cape on the wind, while its 1.3-liter four begged for momentum. Those cars belonged to Jeff. The Mini, loaned by a friend of the event, was perhaps my favorite, a spazzy little wombat with a saddle, but then I couldn’t have a favorite, and if I did, the Boss was the favorite, or maybe it was the Mini, because spazzy wombat, and really, who is supposed to choose on a day like that?

Insane privilege, sampling that list.

And yet.

Forgive me, Jeff, for I am weak at heart and this column has a word limit and we’re just gonna orbit the lady in red.

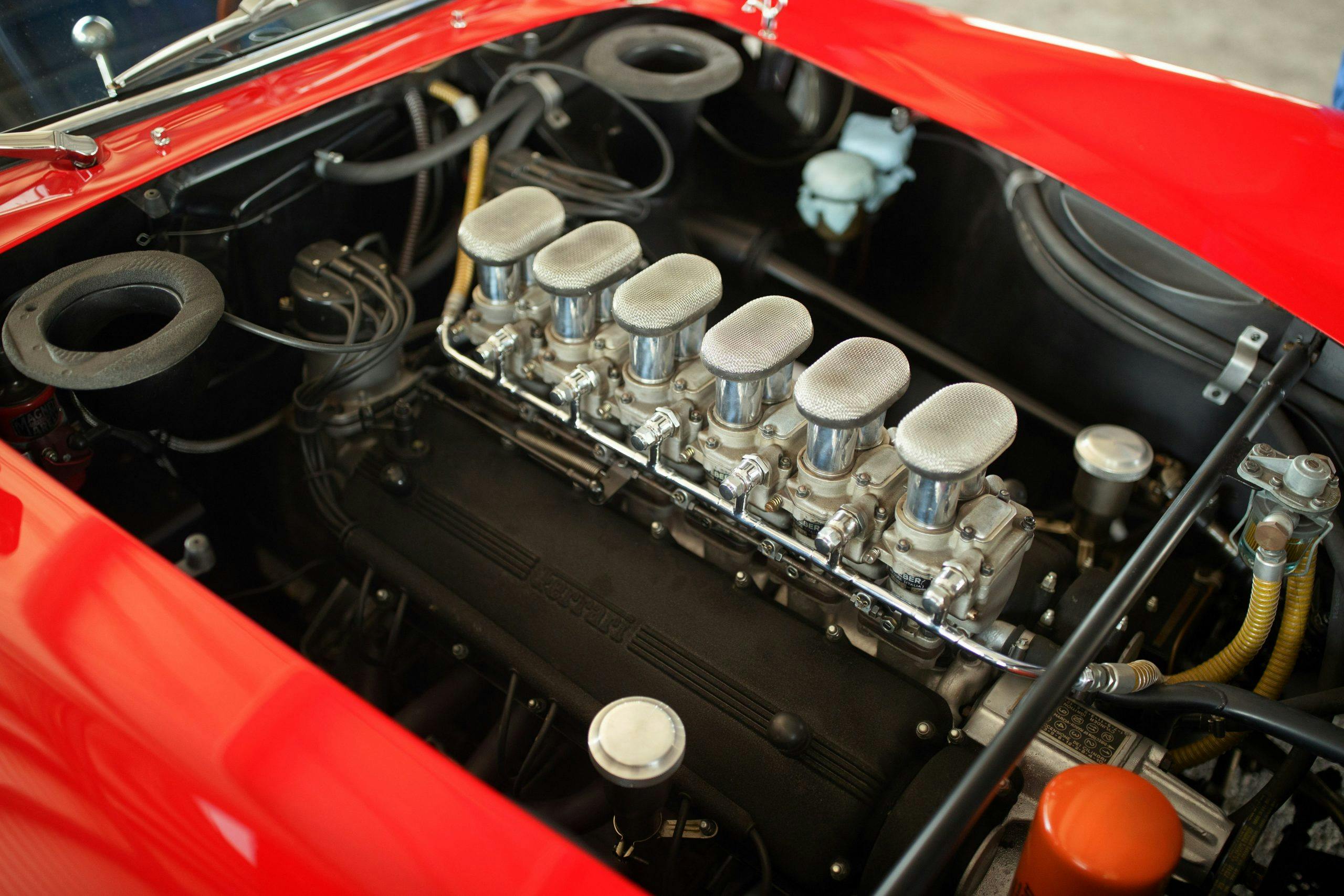

Ferrari built 36 250 GTOs from 1962 to 1964. The model is widely seen as peak jazz and beauty from a marque known for both, which helps explain the price. A GTO currently holds the record for most expensive car sold at auction ($48.4 million, 2018). Another was reportedly the most expensive car to ever trade hands in private sale ($70 million, 2018). Once, these were just used-up old race machines; later, Picassos.

The combination can be a lot to process. Watch those leonine tailpipes spit wet carbon on startup, hear that small twelve rasp alive while the gathered crowd shuts up because the GTO is starting, sit in that taut little blue-cloth bucket behind that wrinkle-finish dash and run a hand across that chrome shift gate, it feels like …

Well, a car. Albeit a pretty one.

I left my phone there at one point, had it fall from the pocket of my race suit while sitting in the passenger seat. I realized this at the end of the day, then went back to the car and spent a few seconds lying on the floor, digging for it. As you would in a Civic. There was chuckling, softly and to myself, because I am the kind of scatterbrained goon who loses his phone everywhere—and why not here?

We are all destined to be ourselves, even while poking around one of humanity’s great tangible metaphors for the impermanence of passion and money.

Discussions of beauty and truth occurred among the gathered. Is 70 million a sane number? No car costs as much because logic. The nature of art values is subject for another time. All I know is that wanted to sit behind that dash forever. Preferably with the engine snarling away, with a beer in my hand and closed eyes and golden sun on my face, like Alonso in that meme.

My passenger ride lasted two laps? A hundred? Who cares? One was the same as a thousand. The springs were soft and those Dunlop sidewalls fat as a mattress. A 3.0-liter Colombo V-12 in that environment sounds as if every brass instrument in history has gathered for some kind of resentful high-school reunion and gotten drunk while singing at women. Two corners in, my spine noted that the car’s roll centers were very likely chosen by someone big fun at parties. I wanted to find that individual and hug them with arms big as God.

O’Neill was forced into slow laps, maybe 70 percent of full pace, because the gearbox was unwell. A dead synchro, failed that morning. It was enough. About halfway through the second lap, I lifted my visor as he drove, yelling above the din.

“It’s so … compliant!”

He waved a hand at the dash, said something I couldn’t hear, eyes lit with emphasis.

“Friendly!” I shouted, the word lost in the wind. We slid through a downhill right in third gear. The car recovered in the same controlled shake that housecats give after falling to the floor and landing in a run. I grew lost in the noise.

Knowing the history always helps. Don’t stop me if you’ve heard it: At the height of his midcentury power, Enzo Ferrari commissions a lighter and more cutthroat version of his epochal 250-series parts kit. (Think 250 Testa Rossa, all-conquering, with those mammary fenders.) Ferrari’s technical department, the heart of the company, is then relatively small, chiefed by a few key geniuses. Shortly after the order is given for the new car, the company sales manager goes to Enzo to protesting the behavior of il commendatore’s wife; she was unkind to employees. Enzo being Enzo, the manager is fired.

The firm’s tech heads band together in protest. Depending on who you believe, those people are then also fired (likely) or get fed up and walk out (less likely). The car that would become a touchstone, the arguable peak of a dynasty, is left to be completed by a mostly younger and less experienced staff. They were undoubtedly watched closely by the old man and almost certainly not spooked, no, of course not.

The new technical director, Mauro Forghieri, was just 27 years old and fresh from engineering school. Period journalists saw the Gran Turismo Omologato he helped finish, called the car ugly, an anteater.

Journalists are often idiots.

I spent much time thinking on that dead synchro. Entropy on the hoof. People in the know were calling GTOs sculpture a decade before the 1980s classic-car boom. And yet the thing’s true nature is seen only in motion: those hips in a slash of yaw, light licking off fenders, the engine whip-cracked through a shift.

Art should be viewed as its creators intended, and cars are more than statues. Michelangelo’s David wasn’t designed to be hucked through a 100-mph corner. The subject matter is inarguably dynamic, the instrument only transcendent when live on stage, but that performance speeds the entropy, wears out the original matter, risks the very object held dear.

That conflict, of course, is exactly why O’Neill built a race weekend. Nothing wrong with protecting your valuables, but the tail shouldn’t wag the dog. GTOs and 917s and the like are impossibly expensive to own and run but widely beloved. They carry lessons about who we are and how we can soar under pressure. If you want those lessons to carry, it is shortsighted to keep them parked and dead to the world.

I have spent years track-testing expensive race cars for work. These arrangements have always involved the sourcing of ample insurance policies, for worst-case scenarios. You don’t think much about those policies on the day of, and it has nothing to do with being a Pollyanna. A car owner smiles and shakes your hand in some paddock, and the two of you agree that safety and mechanical sympathy are paramount. The other agreement is generally unspoken: You will drive the car and not worry on its value, because if you do, your attention will be split off the wheel. The safest way forward requires full presence.

Processes and metaphors. On a long enough timeline, we’re all destined to be parked. So many things we fear on the way there are just reasons to keep moving. Storytelling the past helps suss how the future should work, and old race cars are so compelling partly because they are proof that somewhere, if only for the time between flags, some person lived fully in a moment. It can seem frivolous, to make such a deal of an old thing and its voice, but then, you could say the same about novels or music or anything else we build to keep ourselves sane.

If you can get to Laguna next month, give it a shot. Throw Jeff O’Neill some gate money and wander Monterey in the gauzy morning light. In the end, love isn’t a requirement. No one says you have to stick your face into the exhaust of a running Colombo motor, inhaling bits of unburned fuel like some twitterpated dork. You can have a thoroughly pleasant afternoon without making a point to freeze that memory in your head, replaying it in a loop for weeks after. In those moments where you’re stuck at a keyboard or falling into some dentist’s chair on a cloudy Wednesday or even just clicking through a spreadsheet and doing the math to pay your bills.

You don’t have to love it.

But I am here to report, live from the scene, that it sure doesn’t hurt.

***

Full disclosure: Hagerty accepted flights and hospitality in order to attend the 2021 Velocity Invitational preview day at Thunderhill. The second running of the Velocity Invitational vintage-race weekend will be at WeatherTech Raceway Laguna Seca from November 11th to 14th, 2021.

If you’d like to know more about the cars driven in this story, please visit the author’s Instagram, where he answers direct questions about things like handling and history while also writing extremely long captions of deep enthusiasm that very often contain far too many exclamation points for a grown man.