Picture Car Confidential #5: Trials of the Travelall

With all the happy talk around Volkswagen’s new Scout brand of late, it seems a good time to revisit Scout’s progenitor, International Harvester. And that’s only sort of because we at my picture car business own a 1968 International Travelall. In my defense, the new (for 2028) Scout references the Travelall more than it does the original International Scout of 1961, what with the new-model Scout’s four doors instead of the ur Scout’s two (and Travelall’s four). The upcoming Scout also shares the Travelall’s seating for six instead of the first (and most famous) Scout’s three (or an uncomfortable five, at most, with optional rear mini bench). Electric and hybrid powertrains are all-new for the latest Scout, of course, and won’t play into what corporate masters Volkswagen call the car. But the Scout name sounds more macho than Travelall, while still conjuring upbeat feelings and non-violent themes. So, Scout it is.

As the brand name suggests, what became International Harvester began with a tool for harvesting grain, a nifty new mechanical reaper that was the 1831 brainchild of Cyrus McCormack, aged 22. After a few consequential setbacks, his Chicago-based McCormack Harvesting Machine Company prospered, its namesake’s farm implement business enjoying explosive growth for the better part of the 19th century, with new and improved products catering to the ever-larger farms of the American Midwest as well as smaller farmers looking to mechanize, wherever they might be found. With some 10,000 dealers spread across the agrarian nation, such farmers could, as good fortune had it, be found most everywhere.

After McCormack’s death in 1884, his wealthy and much younger widow and son—taking note of the prevailing corporate practice of chasing monopoly power through the form of trusts intended to sew up entire industries—were eventually persuaded to merge with the Deering Harvester Company, another agricultural machinery giant, and three lesser companies. Thus, was International Harvester born in 1902 in a deal brokered by the world’s master of trusts, JP Morgan, which received an interest in the resulting juggernaut for its troubles.

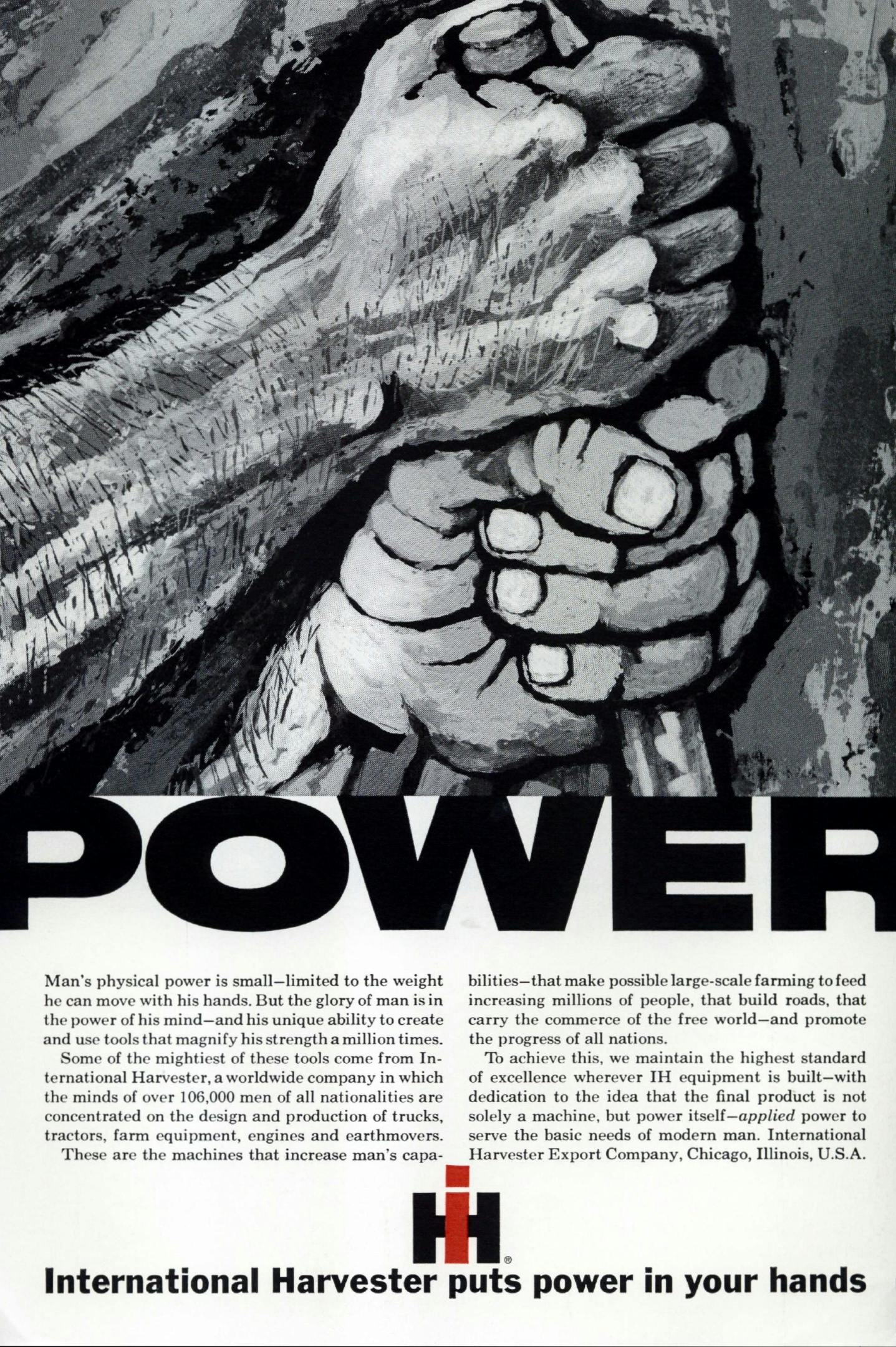

IH was a giant, too, with 85 percent of the U.S. market for farm implements. By 1909, it was the fourth-largest industrial company in America, as measured by assets, and, in 1917, as Gary Hoover has written for the American Business History Center, “it was larger than General Electric, Ford, or General Motors, and as large as all its farm implement competitors combined (four times the size of [John] Deere). By the 1930s, ‘IH’ had 44% of the U.S. tractor market with its Farmall brand, twice the share of competitor John Deere.”

I’ll leave the blow-by-blow farm implement history to someone who knows better, but in addition to tractors, with the coming of the Gasoline Age, a development IH providentially embraced, the firm also built vast numbers of trucks of all sizes from 1904. They were, in the main, quite good. But they were different. (The point of recounting all this history being to illustrate the roots of that difference.)

By the 1950s, when International began selling light trucks to private citizens, International was part of the larger automobile industry and, at the same time, it wasn’t really. Part carmaker and part not, with its own cost structures, labor practices and historic market dominance in the farm implement game, IH viewed its few offerings to non-farm consumers through a different lens. For one thing, its products were those of a company that had successfully made things for hard work for over a century, and they tended to be more rugged than the average Detroit truck or car. But, as the 1950s rolled around, IH wasn’t immune to following the competition, either.

The Scout marked International’s entry into a new market, a four-cylinder Jeep-like thing with a smidgen more luxury (roll-up windows, imagine!) whose only other competitors were the decidedly non-luxurious English Land Rover and, in later years, the spartan, original Ford Bronco. Initially, the audience was intended to be sportsmen. But then came the great sport utility vehicle wave, a tsunami that swept the nation and resulted in many more potential competitors, for whom the audience grew ever larger. As did many of the vehicles.

Most were fancier than the Scout, too, even in its second and final configuration as the larger Scout II, which launched in 1971 and ran until 1980. Similarly, the Travelall, which debuted in 1953 and soldiered on across four series until 1975, was first pitched to hunters and fishermen, then to the trailer-towing fraternity (an irony we’ll get to in a moment), and then to suburbanites as a family ride. Or, as one IH advertisement had it, “America’s Every Purpose Station Wagon.”

And it was a genuinely heavy-duty wagon—lower-riding than other SUVs of the day thanks to torsion bar front suspension, with optional 4×4 off-road chops and amazing visibility out its plentiful glassworks. Whether the new Scout fills its shoes exactly is a thing that remains to be seen, though early word is promising.

Of course, Willys got there first with its Jeep station wagon and later Wagoneer. But for some curious reason, such vehicles and the still-more-similar Chevrolet Suburban, launched in 1935 and today the longest-running nameplate in history, launched with only a single pair of doors. For the capacious GM offering (and the Jeep), it meant passengers entered through the front doors and made their way awkwardly to the rear. So when the IH Travelall—originally offered as a two-door—grew one and then a pair of rear passenger doors, it comprised a class of one. The portal shortage among the competition was not remedied until GM gave the Suburban its fourth door in 1973.

Where, then, does my Travelall fit in? I’ve been a fan since childhood. Growing up, I remember our next-door neighbor, Hal Jones, had a heavily patinated second-gen ’59 that he drove on many a cross-country trip (often up to Empire, Michigan, where his parents had a home, not far from Hagerty HQ in Traverse City). But it was the third reimagining of the model (1961–68) that captured my heart.

By the early 2000s, I’d been admiring a particular yellow 1968 4×4 example for years. Spied many times during visits to the West Coast on a lot at a foreign car garage in Los Angeles’ Silver Lake, it looked just right to me. One Sunday night before leaving town, I passed the shop at dusk while headed to some friends’ house for dinner, noting that the Travelall, all these years later, continued to stand sentry. Leaving at 11:30 p.m. prior to a too-early hotel wake-up call for my flight home, it occurred to me to try and find a name and address for the shop that might lead me to a phone number I might call some future day and see if it was for sale. But as I passed the unlit yard, pen and pad at the ready, I noticed a light was on inside the shop—an omen surely—and parked.

After apologizing for the late evening intrusion, I asked the owner, an older gent, tall and lean, working at a desk, whether the Travelall might be for sale. “Of course, it’s for @#$%&*! sale,” he barked. “That @#$%&%$ @!$%^ is taking @#$%&%$ everything! Everything is for sale.” Once he calmed down, the seller proved a nice guy, knowledgeable and honest, I felt. A veteran airplane mechanic, he’d rebuilt the Travelall’s smooth-running 304-cubic-inch V-8 himself. A deal was cut, and within the week, following receipt of old pal Bob Merlis’ encouraging volunteer road test results, he wired me funds in the low single-digit thousands. The yellow bus was headed east.

It arrived absent one of its twin saddle fuel tanks, a demerit that made itself known while I attempted to fill the missing tank through a filler neck that led to nowhere, realizing too late that my sneakers had suddenly become covered in gasoline. Otherwise, it was great, a rust-free lifetime California truck (explaining the tinted windscreen and optional dealer-installed A/C) with a robust four-speed manual transmission, locking front hubs, and a recent interior in non-original, but serviceable, soft-to-the-touch mouse fur.

Back home, when I hooked it up to a U-Haul trailer months later, I was delighted to find that it would tow at 70 mph, relaxed in a fashion the 1966 Land Rover Series IIA military edition it replaced could only achieve when parked. The Travelall’s ride quality upgrade over the Rover, courtesy of its long wheelbase, well-judged spring rates, and aforementioned torsion bars, was astounding, with more sure-footed roadholding and powerful four-wheel drum brakes. Plus, as an unrelated final bonus, it got better gas mileage, even while towing.

In fact, besides looking cool and possessing interior space to beat the band, towing always was and always will be one of the Travelall’s great natural attributes. It was, after all, the official tow vehicle of Airstream Trailers in its day, pictured in many of the firm’s period advertisements, finished just like ours in International Light Yellow with a white roof (though our truck was originally red). With the substantial grunt of its V-8, the Travelall soon was pressed into service as Octane Film Cars’ de facto first tow car, dragging picture cars to film sets all over New York in the 2010s and occasionally snaring a part for itself. A few failures to proceed for old car reasons aside, the Travelall quickly demonstrated why people loved them and why they still do.

But there was it turned out something funny about the Travelall’s towing legacy. I discovered it one winter’s frosty morn when returning a U-Haul trailer. As he disconnected the trailer, the U-Haul attendant pointed out that the hitch’s ball was flopping up and down. I almost fainted dead away. The hitch, which, in the previous week had been used a dozen times with the rented trailer to transport (separately) three matching dark blue R107 Mercedes 450SLs all over Christendom to the various sets in the remake of the Ingmar Bergman television series, Scenes from a Marriage, was failing. No sooner had we returned the third matching Benzer to its owner than we were being shown this vital piece of equipment, about to fall off.

Closer inspection revealed that the hitch had been welded with simple L-irons to the massive frame rail—standard U-Haul practice. Except the Travelall’s frame unexpectedly ends about 2 feet ahead of the rear bumper. So to be attached to the frame, the hitch was massively cantilevered, creating enough strain over time to break the welds. While mumbling to myself about how they could’ve been towing 24-foot Airstream trailers around with such a Mickey Mouse setup, the Travelall was taken out of towing service. A trip to the forum boards revealed that this was a not-untypical Travelall problem, which even a factory hitch arrangement (that may or may not have existed) could not solve now, if it ever could. The absence of a better system has invited a variety of proposed fixes, some good, most bad.

Fortunately, my friend, Steve Dibdin, an English design engineer living in New Jersey and owner of Additive Restorations of Buchanan, New York, a sophisticated operation that specializes in fabricating unobtainable parts, offered to help. With the use of careful mapping and CAD/CAM drawings he was able to design and fabricate a mounting system that utilized a modern heavy-duty pickup hitch system while minimizing the cantilevering effect through the use of massive four-sided sleeves that fit over the frame rails far enough up (and back) that he calculated it was now good for towing 12,500-lb. loads. That was more than we’d ever attempted, by far, and likely more than the rest of the Travelall was up for, in any event.

Not long after, we broke down and bought a fancy aluminum trailer of our own, which was nice, at least before we acquired a new 2021 Ford F600 rollback truck that beats them all for hauling cars. The Travelall’s towing days are fewer and further between as it’s entered deep backup status. But to the many back-to-nature and paranoid survivalist types, from hippy eco-warriors to off-the-grid militia men—all of whom have embraced this mechanical relic with its deep practical appeal, make no mistake—we understand. The Travelall ethos resonates across the political divide. Why? It looks good, but mostly because it’s tougher than the rest. I know, having once owned a ’70 Suburban, which I liked until it rusted off the road. But once I became a Travelall man, Suburbans seemed like wet paper towels against the indestructible canvas of the Travelall.

When the new Scout does come out, we’ll see whether it’s as tough as nails, like the Internationals of yore. Given the tenor of the times, maybe there’ll be a three-row version added to the lineup, for big families and soccer moms. Perhaps they’ll call it a Travelall.

***

A man of many pursuits (rock band manager, automotive journalist, concours judge, purveyor of picture cars for film and TV), Jamie Kitman lives and breathes vintage machines. His curious taste for interesting, oddball, and under-appreciated classics—which traffic through his Nyack, New York warehouse—promises us an unending stream of delightful cars to discuss. For more Picture Car Confidential columns, click here. Follow Jamie Kitman on Instagram at @commodorehornblow; follow Octane Film Cars @octanefilmcars and at www.octanefilmcars.com.