Music For Your Road, no. 6: The Guitars That Took Over The World, Part 2

This is a continuation of a long essay. Obviously, I think the subject matter deserves extensive coverage.

In Part 1, I examined the societal and technological contexts of the development of the electric guitar. For me, the electric guitar was the most important musical invention of the 20th century. (Not the Theremin; and not the synthesizer.)

I then recommended four guitar albums that have not been played-and-replayed to the point that, for most people, they have become wallpaper.

Here are the other eight guitar records I think are hugely important, and which you are sure to enjoy.

5. Leo Kottke: 6- and 12-String Guitar (1969)

Because of its low cost of entry, its portability, and its playability, the (unamplified, non-electric) guitar was an important instrument in many strains of vernacular American music over the course of the 20th century, from Cowboy music, to Country music, to Delta Blues.

However, for those musical genres, the guitar was usually cast in the role of accompanying a singer. The musical focus was on the vocals. Now: Truth be told, some of the most important folksingers of that period were unexceptional as guitarists.

Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan, I’m talkin’ ‘bout you.

“Folk” guitars were an almost de-rigeur part of “Folk Music.” Bob Dylan played guitar. Peter, Paul, and Mary, perhaps the most commercially-successful Folk-Music group, was comprised of two male guitarists who sang, plus one female singer who did not play the guitar.

James Taylor played the guitar. (So does Taylor Swift.)

Gordon Lightfoot, perhaps the most musically sophisticated songwriter of that era, was a guitarist (and not a bad one, at that). Of Lightfoot, Bob Dylan said “Every time I hear a song of his, it’s like I wish it would last forever.” Billy Joel claimed Lightfoot as a musical inspiration. But I digress.

So, guitars were everywhere in post-WWII America. However, the idea of an audience’s sitting down to listen to a solo, non-classical guitarist playing instrumental music simply was not on most peoples’ radar screens.

Leo Kottke changed all that.

6- and 12-String Guitar was recorded in Minneapolis in late 1969, all in one afternoon, in the running order of the album; and, mostly with complete first takes.

This miraculous recording continues to inspire, and to amaze.

Indeed, Kottke’s example launched not only countless solo-guitar albums (specifically, players such as William Ackerman, Alex de Grassi, and Michael Hedges); but also, in some ways, Kottke set the stage for “New Age” music—despite Kottke’s primitive-folk roots.

Kottke might have paved the way for what, back in the day, I would have called “Fern-Bar Guitar Music;” but his playing had a harder edge.

I think 6- and 12-String Guitar is Required Listening for Cultural Literacy in American Music.

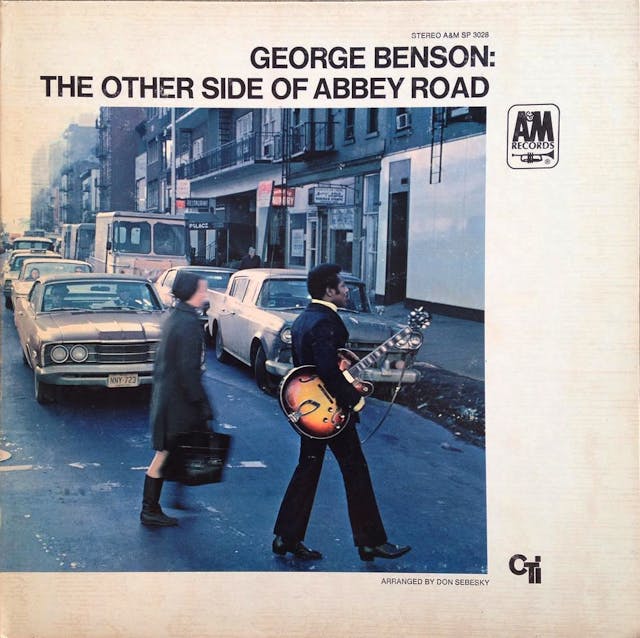

6. George Benson: The Other Side of Abbey Road (1970)

George Benson was a child prodigy on the guitar. At the age of nine, he recorded for RCA-Victor in New York City.

My favorite story about Benson’s early years is, as a young teenager, he was supposed to audition for an agent (or for a record-company executive).

By happenstance, some well-known singer was also visiting that same office, at the same time. (It could have been Sarah Vaughan, or Dinah Washington). The singer (whoever it was) agreed to sing with Benson. She suggested “Summertime,” (from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess).

To which the teenaged Benson responded, “What key?”

By 1970, George Benson had released six albums as a leader. As well as having played (and recorded) with Miles Davis.

With experience like that, the 26-year old Benson was ideally positioned to buy a copy of the Abbey Road LP, quite obviously fall in love with it (as well as assimilating its worldview), and start working on his own re-imagining of it.

Getting into the studio a mere three weeks after Abbey Road‘s release certainly was an inspired case of “striking while the iron was hot.” I think that Benson made the absolute right decision to concentrate on Side 2, to the exclusion of Side 1.

Furthermore, The Other Side of Abbey Road is, I think, an unheralded example of “Baroque Pop,” as shown by the presence of a harpsichord, a string quartet, and various orchestral winds. The session players include Ray Barretto, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, Freddie Hubbard, Bob James, Hubert Laws, Idris Muhammad, George Ricci (brother of Ruggiero Ricci), and Emanuel Vardi.

A neglected treasure.

7. B.B. King: Live in Cook County Jail (1971)

In 1970, after hearing B.B. King play in a Chicago Blues club, the Warden of Cook County Jail asked King if he would be willing to play a concert for the inmates. King agreed. When King informed his record label of this, they advised King to bring a recording crew, and to invite members of the press.

On the afternoon of September 10, 1970, King and his backing musicians had a brief (but sobering) tour of the jail. They then played in a courtyard for more than 2,000 listeners who were predominantly young black males, some of whom had been awaiting trial for more than a year. Apart from the rousing opening number, most of the songs on Live in Cook County Jail are slow blues numbers, with themes of isolation, loneliness, and sadness.

King’s guitar playing is more “vocalistic” than instrumentally virtuosic. (And, speaking as a string-instrument nerd who once watched King play live, I recall that King approached vibrato as might a cellist—King used vibrato most often while fretting notes with his first and third fingers—at least when I was watching him.)

I am tempted to claim that King is the most “economical” of all guitarists. He conveyed more music, in fewer notes, than anyone else.

Reportedly, the inmates (jails have inmates; prisons have prisoners) felt that the concert was an all-too-rare recognition of their humanity. However, King did not leave it at that. The live album became King’s only No. 1 R&B album. King leveraged that publicity into public calls for jail reform; he also co-founded an advocacy group.

8. John McLaughlin: My Goal’s Beyond (1971)

John McLaughlin became at least semi-famous for his hyper-virtuosic jazz-fusion ensemble, the Mahavishnu Orchestra. With the Mahavishnu Orchestra, McLaughlin often played a Gibson electric guitar that sported both a six-string neck and a 12-string neck. Yikes!

However, I think that McLaughlin’s earlier acoustic venture (his third album) My Goal’s Beyond, is his neglected (Ovation “roundback” guitar) masterpiece.

My Goal’s Beyond fell upon the musical landscape of 1971 like a thunderclap. McLaughlin played acoustic guitar not only with amazing speed, but also with startling power.

Please remember that when this record was released (in 1971), Jimi Hendrix had died less than a year before, and the members of Led Zeppelin were still “on their way up” (Led Zeppelin IV had yet to be released).

Electric guitars ruled the post-Beatles charts. Furthermore, outside the guitar-centric world, at the top of the charts, singer-songwriters James Taylor and Carole King were putting the finishing touches on their retirement plans.

Therefore, releasing an acoustical-guitar instrumental (non-vocal) album that was half solo work and half jazz/Indian-fusion chamber music was a brave (or a foolhardy) undertaking.

It appears that McLaughlin created some of the “solo” tracks (such as the justifiably famous “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat”) by recording chords or counterpoint first, and then overdubbing solo lines.

(But before you find fault, please do the same, and then email me the results.)

My Goal’s Beyond’s stellar chamber ensemble included Charlie Haden, Dave Liebman, Billy Cobham, Jerry Goodman, Airto, and Badal Roy. Whew.

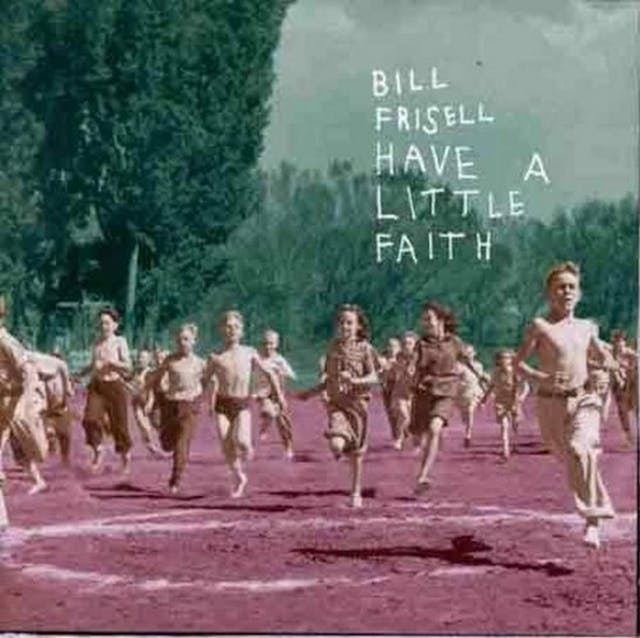

9. Bill Frisell: Have a Little Faith (1992)

It charms me to think that Mary-Chapin Carpenter might later have sat in a chair that I had previously sat in, in a seminar room in the American Civilization Department at Brown University.

If someone were to ask me, “What is the music that tells me ‘What is it, to be an American?’ ” I would immediately reply, Rhapsody in Blue, Porgy and Bess, Pet Sounds, Red-Headed Stranger, and… gee, I dunno; perhaps Have a Little Faith?

While you must listen to this entire album, the standout track for me is the ensemble’s Mex-Tex/Conjunto/Surf-Music re-imagining of Stephen Foster’s parlour ballad “Little Jennie Dow.” (Guy Klucevsek is a national treasure… .)

10. Charlie Haden & Pat Metheny: Beyond the Missouri Sky (Short Stories) (1997)

What a remarkable “Chamber Jazz” album! This album won the Grammy Award for “Best Jazz Instrumental Performance.” The Cinema Paradiso tracks are for the ages.

Purists beware, though… just as the case with My Goal’s Beyond, I believe that Metheny overdubbed his own playing here and there on this record. (Not as much as people think — but when he switches from nylon-string acoustic to his Roland G-303, I don’t think that happens in real time, even though I’ve seen him do just that, on these tunes, live — jb)

In total, Metheny was awarded Grammys in ten different categories. That’s a record I do not expect to see broken in my lifetime. Oh: Metheny, to date, has won a total of 20 Grammy awards.

11. David Leisner: Favorites (2011)

If the “Ciaconna” (or “Chaconne”) that concludes J.S. Bach’s five-movement solo-violin Partita no. 2 in D minor is the “Mount Everest” of violin music (and therefore, in transcription, it is also the Mount Everest of solo classical-guitar music), I nominate, as the “Mount Kilimanjaro” of solo classical guitar music, Benjamin Britten’s Nocturnal after John Dowland.

Britten’s Nocturnal is not so much a set of variations, as an 18-minute reconstruction of a deconstructed “Come, Heavy Sleep,” which is a Renaissance Lute Song by John Dowland.

This being Renaissance music, and also having been written by John Dowland (whose personal motto Semper Dowland Semper Dolens loosely translates to, “If it’s by Dowland, it’s sad”), the subject really is death, rather than sleep.

J.S. Bach’s D-minor Chaconne is a work I consider necessary for Cultural Literacy in Music. Over the course of about 15 minutes, Bach creates 35 different versions of a brief musical pattern that itself manifests internal tension both in rhythm and in tonality.

Chordal statements alternate with single lines or harmonies. The large architecture is that the piece starts in a minor key, changes to major, and then concludes in the original minor key.

The Chaconne is so perfectly constructed that when a good performance or a great performance is over, one truly feels that there is nothing more that can be said. (At least in terms of elaborations upon those musical ideas.)

The Chaconne is so technically (as well as conceptually) challenging that many concert pianists play piano transcriptions of the violin Chaconne in their solo recitals.

David Leisner’s performances of these two sprawling masterpieces should not be missed.

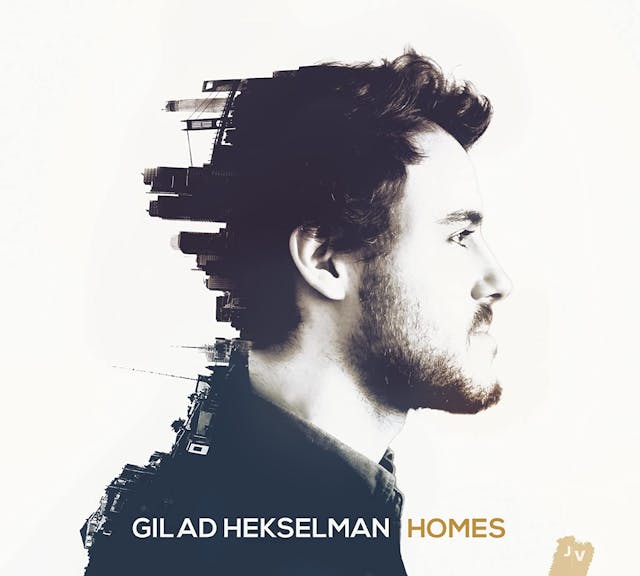

12. Gilad Hekselman: Homes (2015)

Of all the guitarists I have heard who are before the public today, Gilad Hekselman is the one who comes closest to the soundworld of Jim Hall.

IMPORTANT! If you have never seem the semi-documentary 1958 film Jazz on a Summer’s Day, please drop whatever you are doing, and dial it up, one way or another.

(I say “semi-documentary” because the director edited some segments out of chronological order, and also shot some additional footage in New York.)

That said, if you tune in to Jazz on a Summer’s Day (about Newport, Rhode Island’s famous Jazz Festival), you get to see an impossibly young Jim Hall; and that is often what is in my mind when I listen to Gilad Hekselman.

And here’s a list of “So nears, yet so fars.”

I also considered albums from these guitarists:

Chet Atkins, Jeff Beck, Mike Bloomfield, Julian Bream, Roy Buchanan, Robert Cray, Bert Jansch, Eric Johnson, Barney Kessel, Dave Mason, Wes Montgomery, Christopher Parkening, John Renbourn, Andres Segovia, John Williams, and Frank Zappa.

# # #

Here’s a Qobuz link to a playlist of albums five through eight.