EV Sales Growth Has Slowed. Does It Mean Anything?

This past summer, with supply chain issues resolving and factories once again humming, electric vehicles started piling up on dealer lots. Between January and July 2023, reports the trade paper Automotive News, the “days’ supply” (an industry metric used to measure unsold inventory) jumped for EVs, rocketing from a brisk 59 days to a worrisome 111 days. Meanwhile, the inventory of internal-combustion vehicles remained relatively flat in the mid-50s, proving that there were buyers out there, just not for electrics. (As of December 2023, EV days’ supply was 114 days, versus 71 days for the total market.)

An industry that only 18 months ago was rushing head-long to expand battery manufacturing and race to market with full electric product lines suddenly nailed the brakes. Ford, simultaneously reeling from a costly UAW strike, said it will slow-roll an earmarked $12 billion in electrification spending, delaying product launches, cutting production of its Mustang Mach-E electric crossover and F-150 Lightning, and pushing back construction on one of two planned battery plants. GM and Honda likewise said they are scrapping an agreement to jointly produce compact electric crossovers.

On the front lines, Mercedes-Benz dealers were in open revolt over the factory’s unwillingness to put incentives on its slow-moving EQ line of pricey electrics, saying they are losing customers to rivals. Meanwhile, back in 2020, GM offered its Buick and Cadillac dealers a choice: Either invest upward of $200,000 in electric infrastructure for their dealerships or sell their franchises back to GM for cash. Almost half of Buick dealers and one-third of Cadillac dealers took the buyout.

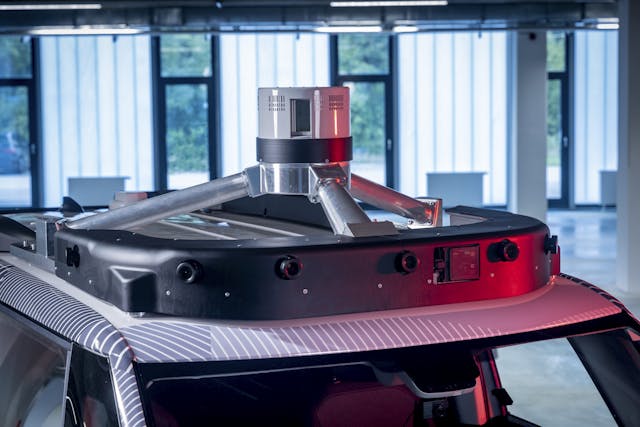

Is the EV transition over before it ever really began? Probably not. The hasty 180 on EV investments likely says less about the long-term viability of electrics and more about present dilemmas. The industry is nursing fresh wounds from strikes and previous bad bets, including Ford’s write-off of $1 billion following the implosion of Argo AI and GM’s staggering $8.2 billion loss (and counting) on its Cruise autonomy division. Add in the turbulence caused by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which places restrictions on EV tax credits so that they apply only to American-made vehicles with U.S.-sourced components, and it’s easy to see why the industry is unsettled.

The ride into an electric future was bound to be bumpy. Now that early adopters have rushed out and purchased electric vehicles, sales growth was certain to slow as the industry gets on with the laborious task of convincing a wider (and more cautious) buying population that EVs are for them. The timing could be better; the market is currently suffering from high interest rates that make new-car purchases more expensive, and there’s a surplus of high-end EV offerings costing $70,000 and up.

Currently the pricing gap between EVs and internal-combustion-engine (ICE) offerings in the hot compact SUV segment is almost $20,000, with electrics retailing above $50,000 while comparable ICE crossovers are $35,000. Sure, tax rebates help close the gap, but the numbers look daunting to buyers watching their dollars. At the same time, older, more affordable EV options, like the Chevrolet Bolt and VW e-Golf, have been taken off the market and their replacements are still on the drawing boards.

Richard Shaw, a retired airline captain in Los Angeles, is an example of the disconnect between consumer demand and industry supply. Four years ago, he bought his first electric car, a new Volkswagen e-Golf, for $19,000 after rebates and incentives. “If you have two cars in the household, you’d be crazy not to have one be electric,” says the EV convert. “They are much cheaper to operate and perfect for local trips, and we find we take the electric way more than the other car.” However, the e-Golf has since gone out of production, as has the similarly priced Chevy Bolt, leaving the base Nissan Leaf as the lone sub-$30,000 electric.

Some buyers may have deferred their purchases in 2023 owing to changes in the Clean Vehicle Credit, the $7500 federal tax credit that, as of this year, allows buyers to use the credit directly as a down payment.

EV sales growth has slackened, but electric cars are still selling—at a rate of about 1 million per year. If EV sales aren’t proving to be a tidal wave, they are definitely still a rising tide.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

For me the EV just doesn’t pencil out $ wise. I have no need of one. I typically drive my cars for 10 years or more, and take good care of them and stay as far away from a dealer as possible. .When I NEED one, I will get one. My neighbor purchased one, bragging all the time about how economical it was. 6 months later he sold it and is now driving an ICE and no more comments from him. The only problem with EV’s is the battery, we are just not there yet.