Cordoba: A socio-economic analysis

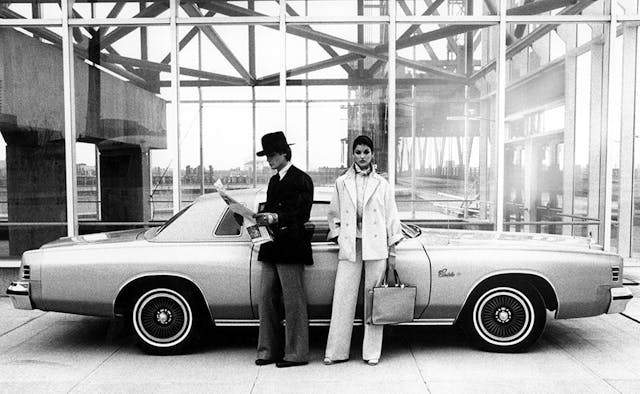

The Cordoba started out its life as a winner, a sales and marketing success. The savior of the Chrysler Corporation and object of widespread consumer desire. The car’s time in the sun was brief but bright; it went from the pages of Vogue to sitcom punchline in a few short years. Historic early sales numbers, especially in the first three years, accounted for 50 percent of the Chrysler division’s total production! As hard as it might be for more recent generation readers to comprehend, company presidents were as happy to pose in front of the car as were fashion models. Sales in the first three years of production were between 140,000 to 165,000 per year, with demand exceeding supply.

Born of the prior generation Charger B-body and initially destined to be a Dodge/Plymouth vehicle, the Cordoba became a car greater than the sum of its parts. Riding on the B-body’s 115-inch wheelbase, the Cordoba used tried-and-true front torsion bars with fore and aft anti-sway bars to offer better-than average-handling that could see you take an on ramp at speed without grinding the rocker panel trim.

But we must talk primarily about design—because, dear readers, we are talking about a time when that is what sold cars. Not technology, range, or implied virtue. Sure, there were Subaru and Saab fans who derided Detroit’s insolent chariots and preferred arcane engineering over style, but they were safely confined to college towns.

The Cordoba’s magic—for surely some small amount of magic was employed by the wizards in Highland Park—was combining just the right amount of neoclassic styling with the prestige of the Chrysler nameplate.

First-person accounts of the Cordoba design process are hard to come by, but the few tales out there often include Bob Marcks and lead designer Steven Bollinger. The Cordoba combines elements of neoclassic design so successfully employed by GM and Ford personal luxury vehicles. There is a hint of Eldorado in the hash mark side marker lights front and rear. The Cordoba in my view is the most GM of all Mopars, beating the General at his own game.

I mean that as a compliment.

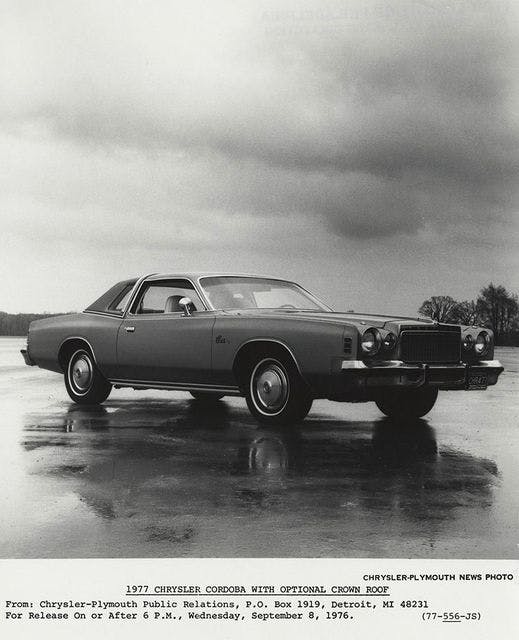

There is a little Stutz Blackhawk in there too. Let’s not forget the influence of Chrysler’s disgraced former VP of design, Virgil Exner; perhaps he got the last laugh after all. In a 1978 commercial Mr. Montalbán even referred to the Cordoba as “a contemporary classic”, which was the very term Exner used to describe his own series of neoclassic reimaginings, including the ’66 Duesenberg, Stutz Blackhawk, and Mercer Cobra amongst others.

Most contemporary automotive scribes made reference to a “Jaguar-like” front end, especially the headlights. If it was a homage, it was complementary not slavish. It obviously worked too, according to the 91-year-old original and current owner of the Cadet Blue 1977 model that helps illustrate this story.

I asked him what had made him buy the Cordoba. I have never owned a new car and given the price of even basic transportation I never will, so naturally I am fascinated by what motivated his decision. Did you special order the road wheels and AC? Why no power windows? A taciturn farmer originally from Scotland, it took him a little while to tell his story.

“I was coming down the steep hill by Battlefield Park (site of a War of 1812 battle in Hamilton, Ontario) and I saw her sitting on the forecourt of McLeod Motors. I had no intention of buying a new car but that front end reminded me of the Jags back home. I never dreamed I could own such a car. I drove her home that day, imaging what my friends and neighbors in the village would they say if they could see me now.”

Somewhere a retired Chrysler marketing executive smiles knowingly to himself.

As it is impossible to hear Beethoven or any piece of classical music with fresh ears, it is equally hard for us to see the Cordoba without the influence of the following decades.

Some of you reading this may have been fortunate enough to have experienced the Cordoba new. I hope I can recapture that feeling.

I have scoured the interwebs for posts on the Cordoba and have found, even in decade-old threads, well before the car was granted some grudging recognition, a distinct current of appreciation threaded amongst the derision of muscle car fanatics. I paid particular attention to the stories of those who bought it new or remembered their parents bringing one home. They are filled with feelings of excitement and want, and the desire for a new product because it was beautiful, not because it was simply new.

• “I followed the delivery truck to the dealer and bought it before it could be unloaded”

• “Mother had to have one”

• “Dad was obsessed, its all he could talk about”

• “I traded a 440 six pack car to buy one”

Sure the Cordoba was designed to flatter class consciousness—but consumers seemed genuinely possessed of an overwhelming desire to own one.

Most former owners have positive stories to tell, most along the lines of: the car was great, wish I never sold it. It is the same with those who got one secondhand or via mom and dad. The Cordoba was usually a reliable car that generated many fond memories.

Safely American but with enough exotic appeal to appease the middle classes’ growing need for European sophistication, the Cordoba was the prefect size for the times. Unlike the dreadnought ’74–’78 C-body New Yorker, the Cordoba was smaller but not small. Socially aware without making a big deal about it.

The name, too, was perfect; the three syllables roll off the tongue like fine cognac or swearing in Spanish. Exotic images dance in your mind. Cordoba is best known as a city in Spain, but it is also the name of the Argentinian coin that became the car’s symbol. The Cordoba’s gold coin was liberally sprinkled over the design, serving as the hood ornament, fender badge and (later in the model run) the trunk lock cover.

The marketing campaign really needs no recap. You can all hear it in your head right now. The mellifluous voice of Khan granting you your true automotive fantasy. Many thousands heard the call and made haste to their local Chrysler dealer.

So successful were the ads that Chrysler bestowed upon their central character a custom-built silver Cordoba with matching silver leather, Maserati air horns and a remote start. And he was proud to drive through the mansion-lined streets of Beverly Hills, where it put to shame the dour status symbols of Stuttgart.

Years later, on Letterman, Montalbán gave a spirited defense of his Chrysler days and stated unequivocally that of course he drove them! Chrysler tried the same trick with the platform mate B-body Dodge Monaco and French actor Louis Jourdan. The ads were equally charming but failed to ignite the buying public to Ricardo-esque levels.

With a debut in the pages of Vogue it is easy to imagine everyone from monied Cadillac owners down to base Mustang II drivers looking at the new Cordoba and saying … that is the car for me. The $4000 base price translates into under $35,000 in today’s dollars. It is the American dream rendered in metal, a personal luxury car that all could own or realistically aspire to. A car that would look good next to the Mark IV or Seville at the country club. No club to visit? One could simply impress the neighbors.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery; the Cordoba’s classic looks were mimicked by the Toyota Cressida and the Australian Ford LTD. I’m sure Chrysler bore them no ill will.

Perhaps most telling is that the Cordoba was once chosen as the perfect platform to entice Americans into hybrids. Those fossil fuel fiends at Exxon mounted a small diesel engine and electric motor to Cordoba to show that the future was still bright, that we could enjoy big-car style while achieving nearly 30 mpg. They even produced a beautiful brochure extolling the Electrocharger’s virtues, a brochure that surpassed the print material of Chrysler itself. One can only weep for the future that might have been.

In 1978 the Cordoba received trendy stacked square headlights. It remained a handsome car, but many mourned the passing of the neoclassic round lamps. Sales started to slide as GM began its first round of downsizing. In 1979 the Cordoba was one of only four cars, foreign or domestic, to pass the federal government’s new crash test ratings.

The handsome ’80–’83 models never stood a chance. Despite being better-styled versions of the Mark VI than Lincoln itself could manage, such Chrysler products were damaged goods at the time. Customers stayed away, returning to the downsized embrace of GM’s G-bodies.

That upwardly mobile dream car in driveways across America was soon becoming an embarrassment. Before the Cordoba name had even been discontinued the car was being mocked as the choice of uncultured rubes whose belt matched their shoes. (Wait, that’s bad? — jb) I’m looking at you, “WKRP in Cincinnati”—in season 3 of that show you can see a second-gen Cordoba.

Fashion models and status conscious housewives turned up their noses and directed their attention towards Europe proper. BMW, Audi, and Benz. The love affair was over. In their eyes, domestic wasn’t a good choice in wine or automobiles. Still the old cars continued to run, handed down to the first born or kept alive by those whose sensibilities were immune to the fickle dictates of automotive fashion.

Traveling around the country on many family road trips in the Eighties, I was always amazed by the number of 1959 Cadillacs stashed behind barns or resting forgotten beneath car ports. I assume even more were hiding behind closed doors of garages nationwide, waiting until they were cool again. My youthful theory was that these cars possessed something special that did not allow the owners to send such works of the designer’s art—however rusted—to the wreckers yard for a cruel death.

The Cordoba has something similar. The car looked too good, made too many good memories. It was Ricardo’s voice they heard in their head, now an automotive necromancer, saving the cars with which he would forever be associated.

A Cordoba is for the moment a good classic car buy. So many were made, and many survive, cherished by original owners and now a new generation unaware of the post-malaise baggage the cars were saddled with. The Cordoba is cool again. You heard it here first.

Yet it doesn’t require a reboot, or dark reimagining as an SUV. It is perfectly fine to enjoy in reruns. We just ask you to remember how the love affair began, and not how it ended:

“it delivers everything I want in a luxury road car”

and, of course:

“……available with fine Corinthian leather”.

had a Cordoba, I bought it from my friend’s mom when her new husband bought here a new Z28 in ’84. It was the same car she drove us around in when we were children. It was a really nice car