Bring back (proper) brochures

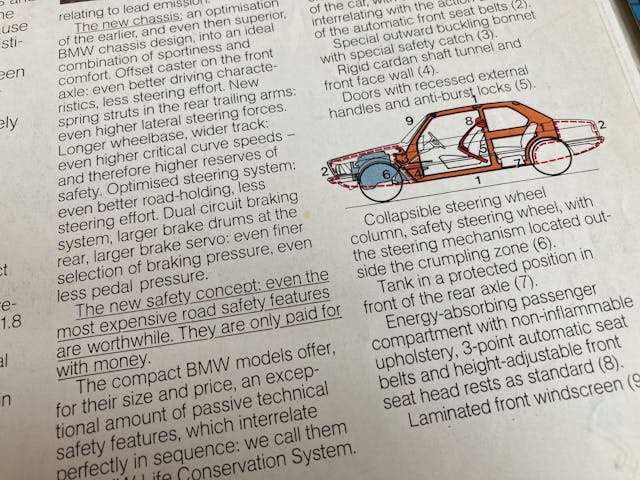

Even the most expensive road safety features are worthwhile. They are only paid for with money.

The words in the E21-generation BMW 3 Series brochure are underlined. It’s not so much subtext as spelled out in enormous neon script.

Later, more underlined text. “The striving for perfection in a motor car is not necessarily cheap, but it is worthwhile.”

They are two of my favorite lines in a car brochure. BMW is making abundantly clear that you might be paying through the nose for your small, kidney-grilled saloon, but you’re damn well getting a better car because of it.

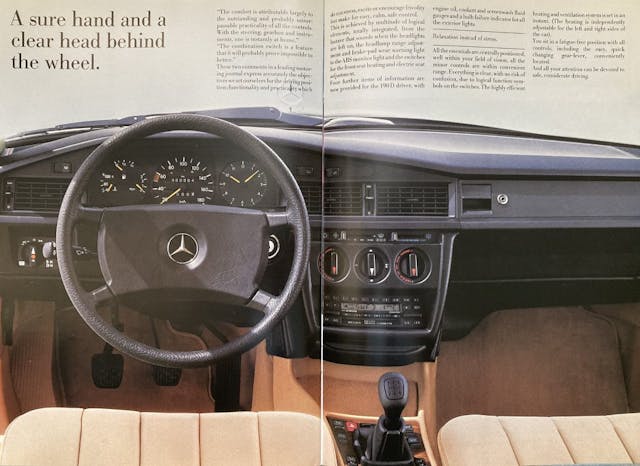

The sentiment is echoed in BMW’s E12 5 Series brochure from around the same time, while Mercedes-Benz, in its 1986 literature for the handsome W201 190D, has a similar message. “Top-quality performance does not, of course, come cheap,” it says. “But with the 190 diesel models you can count on the best possible return on your investment.”

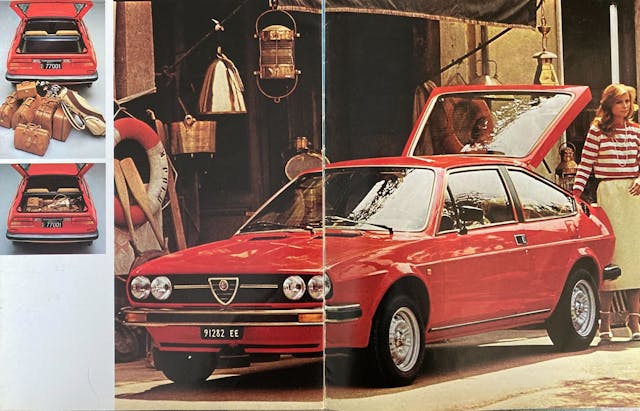

This assurance to the prospective customer that a car was demonstrably better than its competition used to be a central tenet of car brochures.

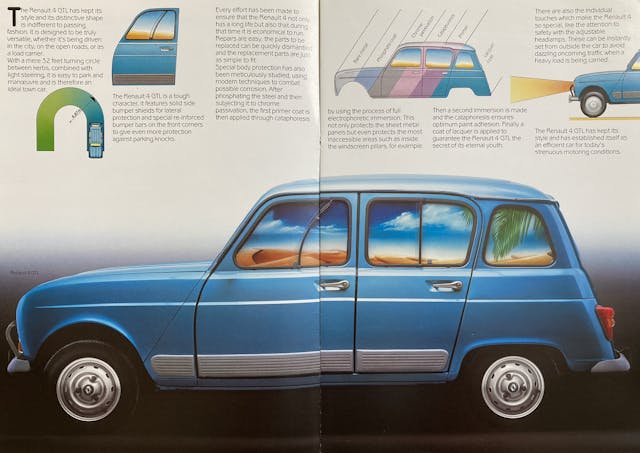

Flip open most Citroën leaflets from the 1950s through to the 1990s, and you’d see several paragraphs on how the company’s hydropneumatic suspension was unrivaled for its bump absorption. Saab would tell you how its cars were safe not just for their crash performance, but because every control was designed to be easy to operate, and its refinement made long-distance driving easier. And the Germans would assure you that your considerable outlay was well-spent on considerable engineering.

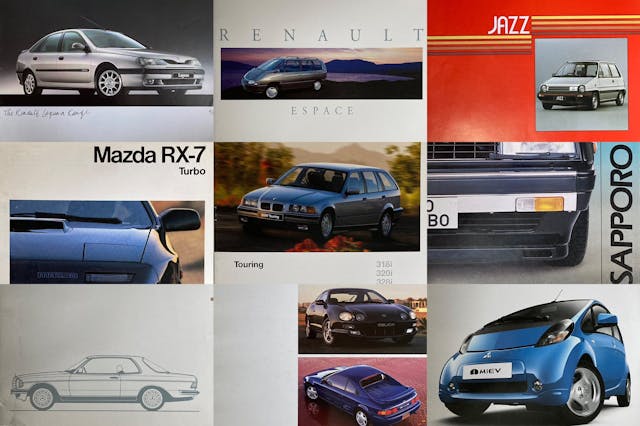

It’s a brand of self-assurance and assumed customer education nearly absent from modern brochures—if you can find them at all. Not only have physical brochures nearly disappeared from car dealerships—removing that kids’ right of passage, scooping up a dozen brochures while your parents do the boring car-buying bit, apart from anything else—but increasingly few manufacturers even offer a downloadable PDF, and those that do make you input your name, address, and your first pet, ready to hold onto your personal details for as long as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation regulations allow.

Journalistic colleagues have been complaining about the latter for a while now, since a good brochure and price list was one of the last bastions of reliable, easily digestible technical information on a car, a useful resource for factual reporting. Whether you wanted to see how much a carmaker charged for heated seats, or wanted to double-check the cubic capacity of a particular model’s engine, the brochure was a one-stop shop that allowed for quick and easy comparison across, say, a model range or with a competitor car.

Today, most of that information is locked away in online configurators, or behind unnecessarily complex and flashy websites, in an ironic but equally annoying parallel with the visually jarring touchscreens that most manufacturers now push on customers.

That’s the other problem. When you do find a brochure today, the information contained within is barely worth absorbing. Page after page on how an infotainment system will apparently make your life better, a few more pages of a well-dressed but bored-looking thirty-something staring out of a café window waiting for electricity to trickle into their EV of choice, and then a few more pages still on colour and trim which, this being 2022, usually offer a choice of eight shades of silver for the body, and six shades of off-white for the cabin.

What you do not get, which older brochures show in abundance, is people who actually look like their lives are being enriched by the car in question. It’s all very clearly staged and always has been, but I’d much rather see people dragging climbing gear out of a brightly coloured station wagon, or frolicking on the beach beside a convertible, or dropping expensive-looking shopping into the boot of a sleek Italian coupé. Such images sell a dream, not simply a product.

People have complained forever that all cars look the same but they’ve always been talking out of their bottoms. There might, however, be a kernel of truth in the idea that we’re approaching a kind of automotive singularity, where you can expect more or less the same experience from almost any car, and perhaps that leaves little room for creativity or differentiation in a brochure.

A brochure used to highlight how a particular engine or significant increase in refinement, safety, or handling prowess would be a genuine improvement on its predecessor or the competition. But we’ve had diminishing returns with refinement, reliability, or the fundamentals of handling for a while now, and the gap between attributes that used to be unique to certain marques has shrunk too.

Your Citroën probably rides little better than your neighbor’s Kia, for instance, so that’s two pages of brochure copy you aren’t going to read. A BMW 1 Series is no less affordable, thanks to PCP financing deals, and objectively little better, thanks to the march of progress, than a Vauxhall Astra. The days of “we’re expensive but we’re better” are long gone.

And why put your car in a quirky scenario to show off what you could do with it, when almost every car is some kind of compact crossover and yours will offer no more or less “lifestyle” than anyone else’s? The battleground is now how much driving you don’t need to do, and how many screens you can gawp at while you’re not doing it.

Thankfully, the likes of eBay, and enormously popular shows like the Beaulieu Autojumble—at which I picked up another 20-odd brochures recently—have made it very easy to find these glorious tomes from the past, even if their newer counterparts have fallen by the wayside. Online prices can feel a bit rich but do make them easy to find, while at the Autojumble some acquisitions cost me as little as 50p (~$1.1), so it doesn’t have to be an expensive hobby.

We’d love to see truly creative and compelling brochures make a comeback, and inspire and inform future enthusiasts and collectors in the same way they have for decades. The sad reality is there’d be little worth reading in them if they did—but at least we’ve got those old brochures as the perfect accompaniment for the cars they helped sell in their day.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

As a car-nut kid, I used to write letters (remember that?) to all the car manufacturers each year requesting their new brochures, which always arrived a week or so later in the mailbox (this was the 60’s folks.) What a thrill to find those fat envelopes waiting for me when I got off the school bus. Those images and accompanying narratives fueled wonderful fantasies of the future, when I might purchase the car of my dreams. Alas, there are few, if any vehicles made today for which a brochure would be worth producing. Transportation appliances – reliable performance, and yes, complete with features not dreamed of in the 60’s – but no character. Thank goodness for classic cars!

My kids raid the shelves at the dealerships we go to now to get booklets on the trucks and cars available, and a couple days later one or two of the pages are tacked to their walls. Mustangs, C8 Vettes, even a GTI Golf.

Sometimes we have to ask a salesman for them, but we usually walk away with something.

I was a pro brochure-designing expert for my corporation. My craft fell into ever-rarer use with the advent of electronic information. I retired (to the tar pits) bemoaning my fate. You’re right that some subtle but essential product information is lost with the demise of brochures, plus the customer satisfaction of having well-produced facts in hand. The essay is well conceived and persuasively written — maybe it will boost my freelancing work.