Avoidable Contact #71: It was 50 years ago today

As a rule, Gordon Baxter was late. Born in 1923, his first love was flying, but after washing out of pilot training in World War II he did not manage to complete his private pilot’s license until his mid-30s. In the meantime he was a turret gunner in a B-17, a merchant sailor on a torpedoed ship, a boatman on the Mississippi River, and a hell-raiser of a disc jockey in eastern Texas, bashing a series of hot-rodded cars through the hedges and fences of Port Author and Beaumont. His first meaningful byline as a professional writer didn’t happen until shortly before his 47th birthday. It appeared 50 years ago, in the August issue of Flying. Just a couple of years later, the always-perceptive Stephan Wilkinson brought him on at Car and Driver—and it is there, as the man enters his 50s, that our story truly begins.

Asked for tips on style and content, Wilkinson told Baxter to emulate Patrick Bedard, saying that Bedard’s work was “comfortable in its own skin.” For nearly two decades, those two men would serve as the magnetic opposites of C/D, with Bedard as the dependable, perceptive southern pole and Baxter as a wandering northern star. It was possible to be attracted to both of them at once, as your humble author was in the late ’70s, an undersized pre-teen flipping to the back of the magazine, then the front, trying desperately to read between the lines of Baxter’s unashamedly adult prose with the limited knowledge set of a precocious child.

It seems unlikely that anything Gordon wrote was ever completely true; even when there was photographic proof of something, the events leading up to that something were described with a searchlight-strength twinkle in the eye. And yet everything he wrote was true, in the sense that his emotion was always faithfully and genuinely reported. Bax loved cars. Loved them for the stories they facilitated, the scenes they set. Loved them for the mere fact of their slightly magical presence in the metal, whether it was the blunt-faced menace of a ’51 Ford Tudor or the finely-hewn folding cowl of a Packard phaeton.

Bax loved women, as well, writing in unstinting but heartfelt fashion about his serial infatuations and infidelities. Like Eugene Henderson, the roman a clef Hemingway substitute in Saul Bellow’s greatest book, Bax could express an “I WANT” big enough to swallow another man’s marriage as easily as he could sweep up a Stearman in a moment of fiscally-unshackled desire. His first wife gave him eight children, but his eyes were always on another prize. In his mid-50s, he simply vanished from his family into a frenzy of personal dissipation, then disappeared again into a swamp with a much younger woman, where he built a house one board at a time by himself and without so much as the hope of rural electric service.

The strength of Gordon’s love and desire was formidable at the time of his writing, but to a young reader raised on our modern “automotive journalism” I imagine it would come across with the force of an F5 tornado. Today’s autowriters can at times appear to be nothing but a group of bloodless, emotionless, sexless illiterates who can conceive of no automotive fantasy other than one in which they are installed as transportation commissar in a future totalitarian state, then given the power to destroy all the things their souls are too small to encompass or comprehend. The only thing they can bring themselves to love is an insipid vision of a deliberately equalized future drawn from Harrison Bergeron as inspiration rather than as cautionary tale. Presented with an extraordinary automobile, their first reaction is to cavil at the cost or clutch their pearls at the environmental implications. Their feckless editorializing can conceive of no higher calling than to limit the freedoms of others: the highest allowable price for a car, the maximum permitted fuel consumption, the fetishistic veneration of speed limits.

Needless to say, Bax had no such mewling hangups, nor did he admit of such limits to his tone, editorial or experiential. Having taken delivery of a Jaguar XK-120, he proceeded to race it for money on the public streets against anyone in any conditions, even thick fog or the dead of night. Writing about the Texan preference for pickups, he cautioned Car and Driver’s readers that their hot-to-trot sports cars would be fair game for any Lone Star resident with a rifle. “… such cars are often shot at, more or less for the fun of it.” One of his most famous columns purported to discover a “venturi effect” that would make it possible for a man to urinate out of a moving car with the driver’s door open at a very specific speed that was, at the time of writing, illegal across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. In the months that followed, the magazine received countless letters complaining that:

a) Baxter’s advice was the most puerile, ignorant, lawless, filthy thing C/D had ever printed;

b) it didn’t always work, with consequences verging on the horrifying.

Bax could work the silver-shining veins of romance in bedrock long ago thought to be exhausted. He wrote with passion about a 1982 Buick Regal sedan, then about the 1984 (Fox/Fairmont) Ford LTD he bought as a dealer demo. Given stronger material, he could be heartbreaking. As his German shepherd passed the age of 15, he wrote:

Wolf can’t spring over the tailgate anymore. He puts his paws up on the lowered gate, and looks around for me to hoist him on up. I lift the fine old dog, and remember the days when he could have jumped over that truck if he wanted to, or towed it. Diane stands in the cabin door, watching us and laughing. I hope someday somebody will do as much for me.

Gordon wrote without the poison pill of ironic distance. It was a crutch he didn’t need, the same way Les Paul and Mary Ford could overdub the same studio track a dozen or even two dozen times in perfect confidence that they wouldn’t make a tiny mistake and have to start all over. Bax always spoke from the heart and spared his readers the coward’s crescendo of insistence that he was not being totally serious about it. That’s how you know he was one of the greats. His writing was unapologetic and masculine at a time when those qualities were not universally considered to be capital crimes.

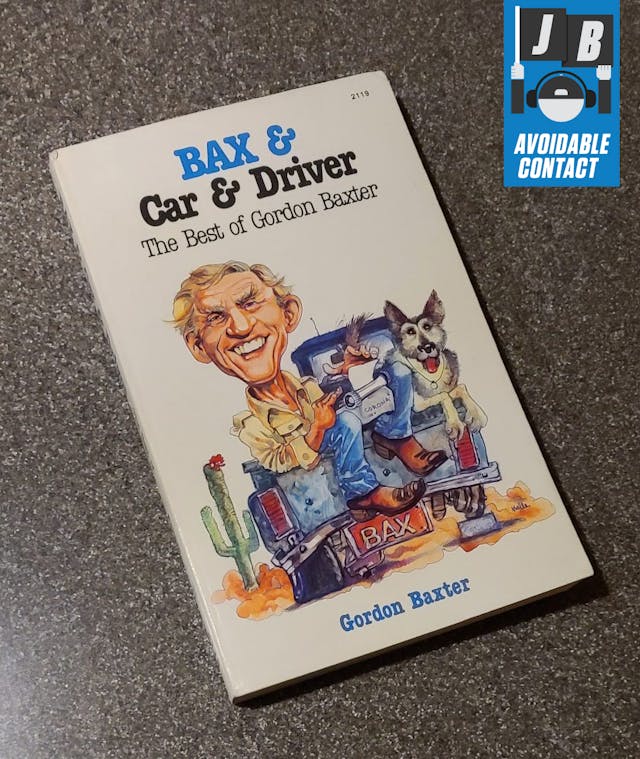

Were he to appear in spirit again today, sprung up from the ground at the age of 46, perhaps a rough-and-ready Afghanistan veteran with a penchant for running a 392 Charger across the causeways late at night and an opinionated YouTube channel, I don’t think anybody could hire him. His work would seem tailor-made for the immediate and disqualifying application of all those … isms. So in that respect, at least, I think Gordon Baxter arrived at his final career in the nick of time, after the dissipation of postwar Puritanism but before the arrival of its harsher and less forgiving descendants. We were lucky to have him. His books are hard to find now, long out of print in most places. If you can find one, it is my hope that you find the same solace in joy in those pages that I frequently do.

A toast, ladies, and gentlemen! It was 50 years ago today. He was here and now he is gone. We were better for his presence and worse for his loss. A toast, please, to the late Gordon Baxter (December 25, 1923 – June 11, 2005).