Avoidable Contact #111: He’s a lousy racer, but you don’t know that, do you?

My long-time readers, if they actually exist, will recall that I was not to the sedan-racing manor (or manner, thankfully) born. Rather, I came to it only after it was painfully obvious that my career as a semi-pro BMX competitor had gone from “never gonna make the Olympics” to “never gonna make it around the track within five seconds of the winner” well before my 32nd birthday. Every once in a while I’ll dust off a bike and go back to BMX for a few weekends. It is reliably humiliating. I’ve won perhaps three races in the past decade, and one of those was against two people who crashed in the first turn.

Compared to bicycle motocross, auto racing has a lot to recommend it, even at the SCCA level. For one thing, it’s a lot easier, both physically and mentally. It’s a lot safer, too. The facilities are nicer. I’d like to tell you that it’s more impressive to the average single woman than riding a children’s bicycle around a dirt track, but that’s not really true; the last time I tried to impress a lady by letting her observe one of my awesome club-racing victories, she ended up buying her own car, getting her NASA and SCCA licenses, and becoming a regional champion in her second season. Cue Legally Blonde’s Elle Woods saying, “Like, it’s hard?”

There is one area where BMX absolutely wrecks motorsports, however, and it is this: You can tell who the best racer is, immediately and without fail. The average BMX race is 50 seconds long and there are no secrets in it. Raw talent shines, hard work impresses, and the combination on the two is incandescent. The first minute of this video will show you. There are eight world class athletes there, but only one is the best.

It’s impossible to buy your way into a BMX victory. Your clothing and equipment have little bearing on the outcome. The difference between a $800 bike and an $8000 bike is usually a matter of inches at the finish line, if that. Strength, skill, work ethic, and heart are all that matter. And everyone can see every moment of your race, right in front of them. It doesn’t matter how well you interview, how you look on video, how you self-promote and network and suck up to the sponsors. There are no illusions in BMX.

Motorsports, particularly wheel-to-wheel racing at every level from Lemons to F1, is nothing like that. It’s mostly about the car, and it has been for a very long time, certainly before the days of Junior Johnson and Mark Donohue. The fastest car almost always wins, whether it’s F1 or Spec Miata. I mention “SM” in particular because it has long had the aura of being a “drivers’ series,” and it does in fact reward a bit of skill (and luck) behind the wheel, but don’t kid yourself that you’ll ever win the Runoffs in a $15,000 SM, or maybe even a $35,000 SM.

Competitors in IMSA have long known that a small weight penalty can turn heroes into zeroes, and a mild technical adjustment can turn someone who was a paddock punchline into a podium-topping Instagram star. Some of the most evocative stories in motorsports history, like the Ken Miles “photo finish” controversy, make it plain that such has long been the case. Did Ford have all the best drivers that year? Of course not. Could any number of drivers have laid waste to the field in the “fenders are free” Moby Dick Porsche? Of course they could have. The driver barely matters in most of these situations.

That doesn’t mean, however, that there is not a significant difference in talent, skill, and effort between various drivers. It just probably doesn’t mean what you think it does, and it definitely isn’t as significant as you probably think it is. Let me start by forcibly shattering a few of your cherished illusions:

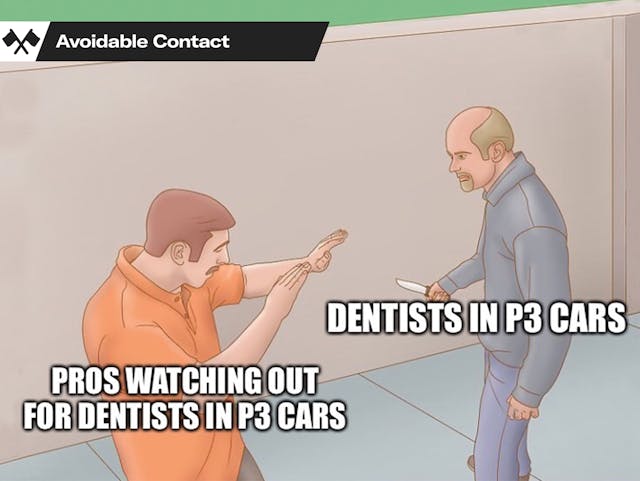

“The Stig” is no faster in most circumstances than your average well-trained 55-year-old club-racing orthodontist. If I had a dollar for every time I heard (or read) someone blathering on about what “The Stig” could do in a certain car, I would have enough money to quit this job and race IMSA P2 all year. Listen to me. Both of the drivers who played “The Stig” on Top Gear were good, solid journeyman pro racers, about as good as 500 other people with similar resumes at the time. If you play an extended game of “Who Raced Against Whom And How Did They Do?” then you’ll eventually come to the conclusion that the “Stigs” weren’t much better than many “gentleman drivers” who pay to race in the United States. There was a much-ballyhooed season a while back where a very famous European racer came to the USA to race Pirelli World Challenge. That racer got beat every single weekend by dentists and lawyers and whatnot until they went home and resumed racing in Europe. If a “Stig” showed up for the SCCA Runoffs, he would likely get thumped by someone who has the name of his father’s industrial-plumbing-equipment company on the side of his Pontiac Solstice. Sorry about that.

If your favorite driver spends a lot of time making videos, acting in movies, or providing commentary, he’s probably not that good. Let me tell you what brilliant racing drivers do for a living: they race. This should be obvious to any rational creature, but I continually hear about how So-And-So-From-The-You-Tubes is the greatest racer alive. (There are many So-And-Sos, by the way.) You want an example of someone who was a great race car driver from start to finish? Scott Pruett. He won at every level despite age and injury. Therefore he always had work, right up to his retirement. Yes, he did some sponsored appearances and the odd bit of color commentary, but he wasn’t out there begging rides in cheap-car enduros every weekend, or making videos, or commenting on Reddit. (Or writing this column; let’s keep it as real as it gets, shall we?) He was working in his field and producing results. If your favorite race driver spends a lot of time doing things that are not professional racing, there’s a reason for that, and it’s not that they would rather run Lucky Dog than compete in IMSA DPi.

Spanks are often as good as pros, and nobody likes to talk about that. In most forms of semi-pro endurance racing, there are two drivers per car. The “spank” pays the bills and the “pro” gets paid. Everyone in the paddock likes to gossip about the spanks who wreck cars, ruin races, and demand to be treated like David Lee Roth in the hospitality tent, but there are also a lot of spanks who qualify well, take care of the car, and win races. I’ll give you an example. Many years ago I had the privilege of being a spank on a very successful Grand-Am team. They won a championship around that time by pairing a wealthy spank in another one of their cars with a famous pro. All year, the spank out-drove the pro. He was faster, smoother, better in traffic. Didn’t break the car, as the pro sometimes did. At the end of the season, the spank took his trophy, left racing behind, and went back to his business. The pro then proceeded to schmooze his way into a dozen paid rides and a lot of opportunities based on that championship, very few of which ended in anything but tears.

Oh, and my “pro” in that series cost us a nice finish in a televised race by breaking the car. No, I’m not bitter. It was only 13 years ago. I can still talk about it, right?

Who’s the best driver in the world? It isn’t Lewis Hamilton, or Max Verstappen, or anyone who ever won LeMans. It’s some 17 year old you’ve never heard of, racing karts or open-wheel somewhere. Who’s the next best? Someone just like him. Who’s the best after that? Another someone just like him. You’ll never meet these people. They quit because they don’t have enough funding for the next season. Racing runs on money. One of the most talented drivers I ever met was a young man named Jesse Lazare, who won a Rolex Daytona before he turned 20. He could win at any level, but right now he’s winning in the Canadian Nissan Sentra Cup. Why? Because that’s all the funding and sponsorship he has. There are a hundred Jesse Lazares. All of them could effortlessly wipe the floor with (insert name of someone you’ve admired in a pro race). But they’re out of money.

Alright, we’ve busted a few myths. What makes a great driver, and what can a great driver do that others can’t? Let’s build a list of skills, from easiest to hardest:

Turning a fast lap, under pressure. This is table stakes. It’s assumed you can do this at any level from SCCA on up. If you think Fernando Alonso could get in an SCCA regional champion’s car and go two seconds a lap faster, you don’t understand racing. At best it would be a half second. Heck, he might be slower.

Working through traffic in an actual race and making the most of every passing opportunity. Almost table stakes. Most club racers and spanks can do this, no sweat.

Doing the above, consistently, lap after lap. This is a little rarer, largely because it requires you to have a consistent diet of seat time in the cars involved. If you put me in a car I’ve never driven for a race, I’m going to have 5–10 bad laps. Jesse Lazare will have one. Scott Pruett might have none, because his experience covers so many cars that he will likely be able to figure out the situation immediately, the same way you could drop John Coltrane into a tune he didn’t know and still get a great solo.

All of the above, plus be easy on the car. This is where the real voodoo starts. Anybody can turn a series of fast laps if they aren’t concerned about what condition the car will be in when their teammate gets in to finish the race. A driver who can run within one second of fast-lap pace while conserving brakes and tires for the next driver, or for a last-lap hero pass in sprint racing, is special. He can make opportunities for his team. He can make his co-driver look good. He can make everyone in the paddock wonder why his car finished 13th instead of 19th. People notice that sort of thing.

All of the above, plus follow team directions to the letter. I’ve raced with a few drivers who had many virtues behind the wheel but who couldn’t do what the team asked them to do. In particular, I’ve known several fellows who refused to back off on pace in order to conserve fuel or tires or brakes. They didn’t want people to see a slow laptime next to their name on RaceHero or on YouTube. If you have this kind of ego, let’s hope you have an income to match, because nobody will ever pay you to drive their car. Not twice, anyway.

All of the above, plus be an active participant in your team strategy during the race. A driver who can do everything the team asks while also keeping a keen eye out for potential advantages on-track, out of the sight of the pit wall, is a true prize. Dale Earnhardt, Sr. was like that. He was always thinking about ways to win that didn’t involve just being faster than the other guy, and he enjoyed the absolute trust of his team.

All of the above, plus keep a mental model of every other team’s position on track, their pace, their likely strategy, and the ways in which events on-track could affect that strategy in real time. Let’s just call this person “Alain Prost” … although I’ve seen people who could do some of this in cheap-car endurance racing as well. My personal lifetime goal as a driver is to operate at this level. I think I did it once in my life, and all I got for it was $1500 in nickels.

All of the above, plus lead the team in every facet of operation, plus build the team and/or car from scratch to your requirements. The alpha example of this is Michael Schumacher, but Mark Donohue also comes to mind. A driver like this is a once-in-a-generation creature.

Yet even Herr Schumacher couldn’t make a bad car turn good in a hurry. Which brings us back to the first point made in this column: in motor racing, it really is mostly about the motor. Or the rear wing. Or the tire compound. Choose your favorite driver, cherish them, follow their career, buy their merch—but keep your expectations in line. Fernando Alonso in Lewis Hamilton’s cars, with the same level of support, is a 10-time World Champion. But he’s not. Because he didn’t get the car. If you want to watch a sport where there’s a man (or woman) and a machine, and the former matters more than the latter, you’ll need to choose something else. Like cycling.

But not just any cycling, mind you. Laurent Fignon lost the 1989 Tour to Greg LeMond by eight seconds. Someone went back later and calculated that Fignon lost something like three minutes by refusing to wear a helmet during the races. The aero penalty of Fignon’s blonde ponytail cost him the victory. Man, that was stupid, and vain, and ridiculous. Totally unworthy of a great road racer. Absolutely typical of a BMX dirtbag like yours truly. Laurent, you can borrow my race bike, or my race car, any time you like.