Olivia Rodrigo and “drivers license”: Pondering A Cultural Phenomenon

Back in the day, when people bought recorded music on physical media (such as Long-Playing (LP) vinyl phonograph records; Philips/Norelco analog-tape Compact Cassettes; eight-track endless cassette tapes; and, later, Digital Audio Compact Discs), the conventional wisdom in the pop-music end of the record industry, as it was explained to me at the time (by “insiders”), was that the most-avid buyers of pop recordings were teenaged girls who had not yet gotten their driver’s licenses. That was pretty much an article of faith.

The thinking that seemed to be behind this common perception was that the shared experience of listening to favorite recordings was a prime social activity among girls from pre-teen through age 15. The girls would gather (or, perhaps more accurately, lounge; or, sprawl) together around a “suitcase stereo” in someone’s bedroom.

However, once the 16-year olds had obtained their driver’s licenses, increased social mobility was the consequence of their newly enlarged physical mobility. Soon, many of that former peer social group had part-time jobs other than babysitting, and perhaps even boyfriends. The received conventional wisdom was that the young ladies slowed down their own music purchases, listening mostly to what their boyfriends had on hand … those were the days of physical media, after all.

I think that it would be a mistake to jump to the conclusion that the avid record buyers in the under-16 female demographic were only interested in “teenage heartthrob” young males such as Davy Jones (of the Monkees), or David Cassidy, or Justin Bieber. The girls also absorbed recordings by teen idols such as Debbie Gibson, “Tiffany,” Miley Cyrus, and Taylor Swift. Even Madonna. Those female performers were often, to an extent, role models (or, future role models.)

I hasten to confess that, to the extent that I ever was successful as a record producer, my success was in classical music. Nonetheless, I was (of course), aware of pop-music trends. Furthermore, some of my “industry friends” were in the thick of it.

I had a cordial relationship with Herb Belkin, a legendary music-business “Insider’s Insider.” (Star-struck admiration for Herb on my side; bemused befuddlement over me, on Herb’s side.)

Herb once said to me, in affectionate exasperation, “You’re such a ‘muso’.”

I think Herb meant what he said in the sense of, “Hey, kid; this stuff is for selling; and that’s pretty much the end of it.”

Perhaps the real lesson is, if you are the sort of person who falls in love with cute little furry animals, don’t go into the chinchilla-ranching business.

Herb is the only person I have ever heard use the band Grand Funk Railroad as a benchmark. At dinner once, at a very nice restaurant in Newport, Herb rather loudly uttered words to the effect that, except for the fact that Eric Carmen was a total (insert expletives here, a few self-referential), his band the Raspberries “would have been as big as Grand Funk Railroad.”

At that moment, it seemed to me that Herb was trying to tie the handle of his elegant coffee spoon into an overhand knot. (That is not the kind of thing one forgets.)

Where was I?

Ah. I have never seen any hard data to back up that years-ago conventional wisdom that had been imparted to me about teenage girls, music-buying habits, and driver’s licenses. Perhaps that wisdom was more conventional, than it was wise.

That said, there is no question that, ever since the automobile industry, pioneered by Henry Ford, began cranking out automobiles that people who worked in factories could afford, the automobile has had profound impacts upon American society.

Some of the most profound impacts having been in the spheres of dating, mating, and family formation.

To translate that, from Sociology-speak, into Plain English:

While, in the 1890s, young couples courted on the porch swing under the watchful eyes of their elders, by the late 1920s, parents (no doubt justifiably) feared that their daughter’s boyfriend’s family’s sedan would serve double duty as a “motel room on wheels.”

Those seismic shifts in culture and society took place from the mid-1920s, through the WWII era.

The advent of affordable, reliable car radios added a fascinating nuance to the social (and especially, the dating, mating, and family-formation) dimensions of the automobile. Although car radios were generally available as optional accessories by the late 1930s, those were vacuum-tube devices, which were comparatively expensive.

The maturation of the first cohort of the 20th-c. U.S. Baby Boom (early 1960s) coincided with the proliferation of affordable and reliable solid-state (transistor) auto radios. Transistor car radios had the additional benefit of drawing far less current when playing while the car was parked with its engine off.

Therefore, there was less risk of enduring the embarrassment of being stranded with a dead battery, in some well-known local Lovers’ Lane.

“Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” indeed!

Writing a song about writing a song to be played on the radio and heard on the radio was an inevitable consequence of the importance of car radios in society and in the record business. Even if the prime such song (which was heard on car radios) was James Taylor’s “Hey Mister, That’s Me Up on the Jukebox.” (Poor baby. Does contemplating your bank balance no longer comfort you?)

I think it is fair to say that obtaining one’s first driver’s license long has been a prime Coming-of-Age event for mainstream American society. Furthermore, even if one does have a Bar/Bat Mitzvah, a quinceañera, or even a Debutante’s Ball … one’s first driver’s license is usually regarded as an emblem of maturity, responsibility, mobility, freedom, and ever-expanding horizons.

Perhaps the most poetic (and cultured) hymn of pop-music praise to the automobile as an engine of freedom is Phil Ochs’ (may he rest in peace) 1970 Rockabilly anthem “My Kingdom for a Car.”

Ochs’ song’s title and refrain wittily (and ironically) riff off Richard III’s (Shakespeare’s character’s) famous cry, “My Kingdom for a horse!”

I’ve found my freedom

Her and I been flying down that highway of gold

My shirtsleeves are rolled, my Colt 45 is cold.

I go fast, ’til I’m going faster.

Look how far we’ve come, look how far

A car, a car, my kingdom for a car

How I love the highway

Picks me up and takes me wherever I please

I race through the trees, bring space to her knees

I am master of all that’s flying past me.

Look how far we’ve come, look how far

A car, a car, my kingdom for a car

Look how far we’ve come, look how far

A car, a car, my kingdom for a car

Lyrics © 1970 Universal Music Publishing Group

Fast-forward, to Anno Domini MMXXI.

Olivia Rodrigo’s hit single “drivers license” is a world-bestriding Colossus.

I have little-to-no idea what a “power ballad” (which is what Wiki calls it) is.

Therefore, in terms of musical form, I will call “drivers license” a ballad, that nonetheless has echoes of a lullaby within it—the slow rocking rhythm, and the repetitive phrases … as though (for most of the song), Olivia is trying to sing her soul to sleep.

People respond to that. Especially teenaged girls. Even the New Yorker.

Except, I’d file the New Yorker write-up under “Frenemy.” It meows, “One of her greatest assets is her ability to create the illusion of intimacy … ”

(I’ve heard a variation on that theme before. In the mid-1970s, a record producer in Nashville, at a record-release party, deadpanned to me, “I’ve always said, that once you can fake authenticity, you’ve got it made.”)

Here are the impressive numbers.

Biggest first week ever, for a song on Amazon and Spotify. Rodrigo then became the youngest person ever to have their first single debut at No. 1 on the Billboard chart. She also set a record for the largest number of single-day streams for a non-holiday song. Her music video has had 228 million YouTube views. However, most of you already knew all that. (I did not; until Eric Weiner kindly brought her to my attention.)

Despite the impressive numbers, I think that it is absurdly, laughably premature to pronounce “drivers license” The Song of the Decade. Puh-leeze. We’ve got eight or nine years to go.

It’s as though with-it critics (who really should know better) have been competing to out-do each other in praise … for extrinsic reasons. Truth be told, “drivers license” is not that great a song, or vocal performance, or production. But, even today, most people still remember who Tiny Tim was, right?

Now, Ms. Rodrigo had already had a good running start on pop-music superstardom. She has starred in Disney’s High School Musical TV series (I intentionally omit the entire, tediously post-modern, knowing-wink name of the series).

Furthermore, erm, um, Ms. Rodrigo has actually made publicly available some of her recorded music before. Therefore, to claim somehow that “drivers license” is her first “official” single (on the premise that her previous releases were “Original Cast” releases from the Disney TV show) seems to me to be a Jesuitical distinction that would make most Jesuits blush.

Whatever.

Name recognition drives a lot of the music business. That’s why it’s so hard to break through the clutter, and get discovered.

I hereby bet $5 that, if besieged Congressperson Matt Gaetz were to make a quickie single recording of “Wichita Lineman” (or even a karaoke version), tens of thousands of people would pay to own the download. Just because.

By the way, a prominent British critic stated that “Wichita Lineman” the greatest pop song ever composed; while the BBC noted that it was “one of those rare songs that seems somehow to exist in a world of its own—not just timeless, but ultimately outside of modern music.”

In the same way, I think that the future reputation of the title track from Brothers in Arms has absolutely nothing to fear from “drivers license.”

Therefore, the name recognition of a Disney TV-series star is not to be ignored in accounting for this song’s truly remarkable (and, for me, verging on incomprehensible) commercial success.

Another, most likely unquantifiable, factor is the teen angst and loneliness spawned by the isolation enforced by the pandemic lockdowns, coupled with isolated teens’ using the echo chamber of electronic media as their Village Green.

Olivia Rodrigo’s song “drivers license” explores the Kierkegaardian dilemma whether to surrender to the Taylor-Swiftian temptation to use one’s newly-acquired driver’s license to drive through the suburbs, with the sole intent of getting a glimpse of the exterior of the home of the cad boyfriend who just dumped you.

Dumped you; and, for an “older”(!) blonde.

However, I assume that when Ms. Rodrigo sings of Ms. Blonde’s being “so much older than me,” she means circa 19 years old, and not circa 34 years old.

As the cases with (the infinitely more-significant, real works of art) Brideshead Revisited and The Go-Between, the sight of the formerly-welcoming, now-shuttered past-love’s abode stirs agonizingly powerful memories.

The overwhelming feelings are of pain, loss, and regret; and perhaps, even self-criticism, for not having soon enough realized that he was a loser, a poser, a hoser, and a totally faithless tool.

But! She still loves him!

The lyrics start with a flashback to their earlier days of bliss, when Mr. Young Cad encouraged his beloved ardently to apply herself to her Driver’s Ed studies:

I got my driver’s license last week

Just like we always talked about

’Cause you were so excited for me

To finally drive up to your house

But today, I drove through the suburbs

Crying ’cause you weren’t around

And you’re probably with that blonde girl

Who always made me doubt

She’s so much older than me

She’s everything I’m insecure about

Yeah, today, I drove through the suburbs

’Cause how could I ever love someone else?

And I know we weren’t perfect

But I’ve never felt this way for no one

And I just can’t imagine

How you could be so okay now that I’m gone

Guess you didn’t mean what you wrote in that song about me

’Cause you said forever, now I drive alone past your street

Lyrics © 2021 Olivia Rodrigo, under exclusive license to Geffen Records

Intentionally or not, I think that “drivers license” draws a line in the cultural sand.

For the Beach Boys, Jan and Dean, and other earlier Bards of the Boulevard and of the drag strip (including Phil Ochs, but only to the extent Ochs might not have been being totally ironical); driving a car was both a pleasure in and of itself, and a means to explore “the territory ahead.”

As in, I get into my car to find out what life has in store for me. The possibilities are as endless as the road is open.

However, for Ms. Rodrigo, the car is merely the most convenient and reliable means at hand with which to torment herself. (“Reliable,” because, if she were to harass her fbf and his new gf with a torrent of abusive, threatening text messages, she might very well break out in handcuffs.)

What strikes me about the music video for “drivers license” is its existential darkness.

I do think that it is a clever musical reference to have the song start with a toy piano sound that mimics her car’s “Door Ajar” alert sound, while the solitary car is seen from a drone’s perspective, at night.

The scene in which she seems to be confined in a room where a video projector projects onto her face and body the word FOREVER in white, on a blood-red background, is as creepy as Kafka (but updated to the 21st century).

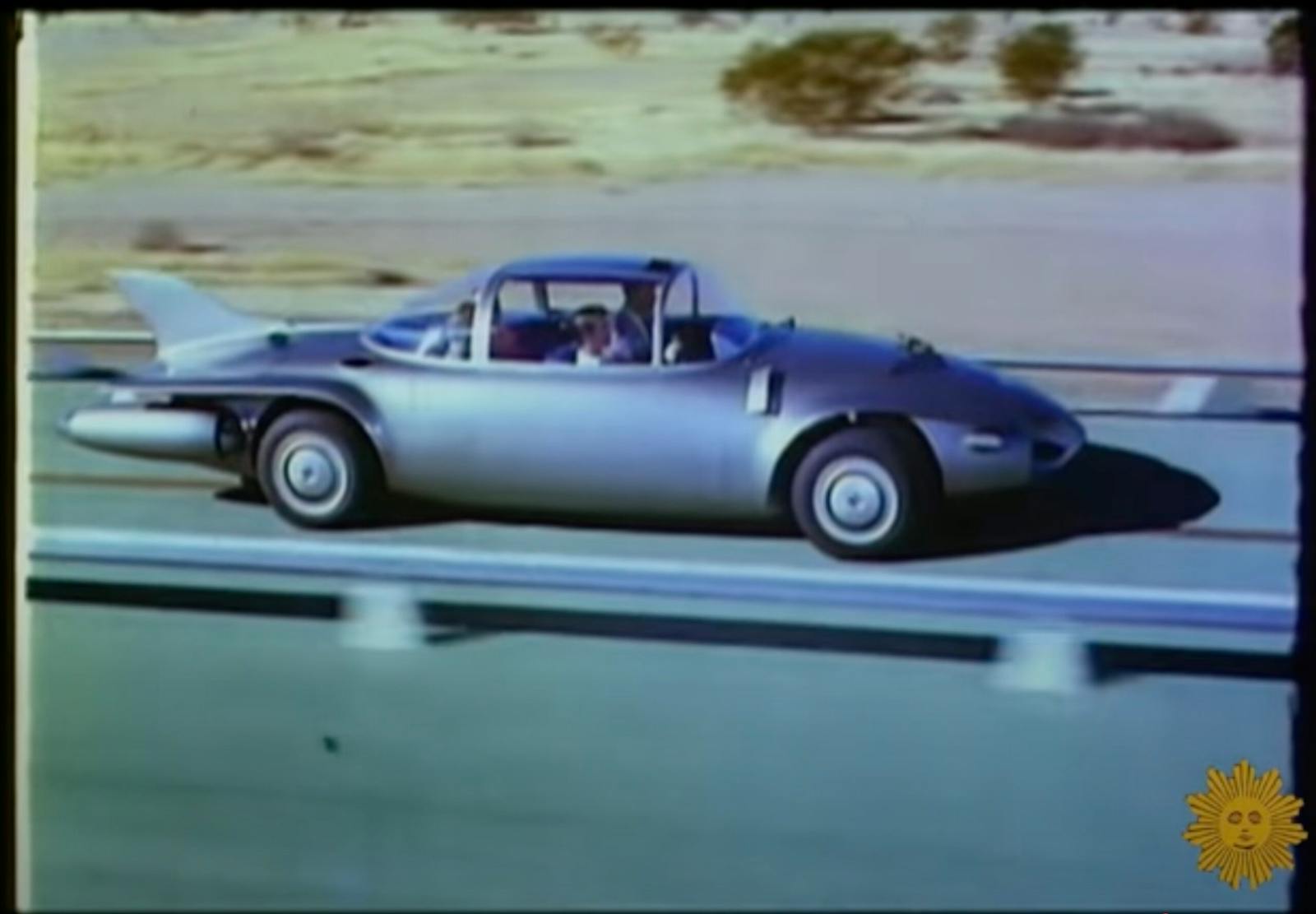

BTW, is Olivia’s car really a vintage (1971–1981 C107) Mercedes SLC?

Being a star must really suck, is all I can say.

Olivia’s so distracted that she didn’t even close her car door completely. There are daylight scenes, but also many nighttime scenes. And of course, the totally paranoid Red Room scene. She can’t take note of the world around her; all the drama is inside her head (and her heart).

That, I think, is the key to this song’s flypaper attractiveness, at least for many people.

The ancient Greeks watched live-drama tragedies (because television and soap operas had not yet been invented), vicariously to experience pity and fear, both of which can be rather addictive emotions.

I think that what is going on with “drivers license” is that you have a setup that provides the context of the emotional crisis, and then a musical eruption that mirrors, and attempts to exorcise, the emotional crisis.

One of my most important mentors in music was opera impresario Boris Goldovsky (of Texaco/Metropolitan Opera radio-broadcast renown), who famously quipped that when confronted with abandonment, betrayal, or violence, the natural human reaction was “to sing about it.”

At the end of the day, I think that “drivers license” is commercially successful simply because it nestles very comfortably into the genre of “Cruelly-Betrayed Operatic Soprano’s Heartbroken Aria of Grief”—complete with a chorus, sung by a chorus, which starts on the lyric:

Red lights, stop signs

I still see your face in the white cars, front yards

I am not claiming that “drivers license” is a full-tilt/full-boat “Grand-Opera ‘Mad Scene,’ ” such as found in Lucia.

I’m just saying that the song’s narrative arc and musical tactics have a history that goes back more than 400 years.

To paraphrase George Santayana, “Those who do not learn Music History are doomed to repeat it; but sometimes, they really rake in all the money.”

And the genius, the “Killer App” here, is that almost nobody realizes that they are, in fact, buying a bit of: Opera.

Nice job, kid.

Just stay away from investing in chinchilla ranches.

…

My absolute favorite such “Female Pity-Party” music video is Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn”:

which, by the way, has racked up 220 million views.

And, for my money, the most “Operatic” pop breakup song ever sung by a woman is Linda Ronstadt’s Baroque-Pop classic, “Long, Long Time”:

It’s obvious to me that back in the day (1970), Ronstadt was gunning for Maria Callas’ job at the Metropolitan opera.

# # #

[Endnote: John Marks, as a record producer: Nathaniel Rosen, Bach solo cello suites: In-flight music on U.S. Presidential aircraft Air Force One; Grammy® nomination. Arturo Delmoni, album Songs My Mother Taught Me, track Glück, “Dance of the Blessed Spirits,” production music on a US #1-box-office major-studio feature film (Heartbreakers; Sigourney Weaver, Jennifer Love Hewitt). Arturo Delmoni, album Rejoice! A String Quartet Christmas, production music on the #1-rated U.S. daytime drama (The Young and the Restless). Guy Klucevsek, album Transylvanian Softwear, finalist, Record of the Year, Stereo Review magazine. Hagerty community people with long memories might remember John’s writing for the Mercedes-Benz Club of America’s STAR magazine. John also once worked in a shop that made tube-frame SCCA race cars.]