This feral Buick GS drag car returned to the strip after a 25-year absence

“This is the dinosaur tour.” A perfect one-liner to describe the age of race cars in attendance at the 40th Annual Buick GS Nationals. Unlike many hi-po drag meets, where late model cars reign supreme, the rides packing Beech Bend Dragway’s paddock are primarily pre-1985. David McIntosh, the man who supplied the quote, has plenty of these short and sweet sentences, keeping any conversation as pleasant and airy as whipped chocolate mousse. I could listen to McIntosh talk all day—automotive knowledge that comes from over 40 years of running your own engine shop and a heft of good-naturing ribbing, piped through a breezy Georgian drawl—but he’s got places to be. A staging box specifically, to ignite the porky slicks on his 1971 Buick GS drag car.

It had been 29 years since McIntosh’s gold GS (badged as a GSX) staged the Christmas tree at Beech Bend Dragway in Bowling Green, Kentucky. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, McIntosh and his drag car were legends among the Buick faithful packing the festival grounds, and the racer spent much of his year prepping customer’s engines for the big meet at his machine shop. “Everything in my life was AB: after Bowling Green.” Back in ’92 the car hit 139 miles-per-hour at a 9.71-second elapsed time through the quarter mile. That year, he was crowned victor at the show, beating the all-Buick field known as the “Quick 16.”

In the years following, McIntosh was always heavily recruited to come back to the strip, but the stars never aligned again during 1990s. The racer and his wife had their son Donald 1993, and, in 1996, Donald campaigned the gold Buick for the final time. That is, until this year’s GS Nationals. The prospect of a return for the torqued-out muscle car to the momentous iteration of GS Nationals at Beech Bend this year provided the proper push for McIntosh to dust off the old Buick and trailer it up to Bowling Green from his hometown of Dawsonville, Georgia.

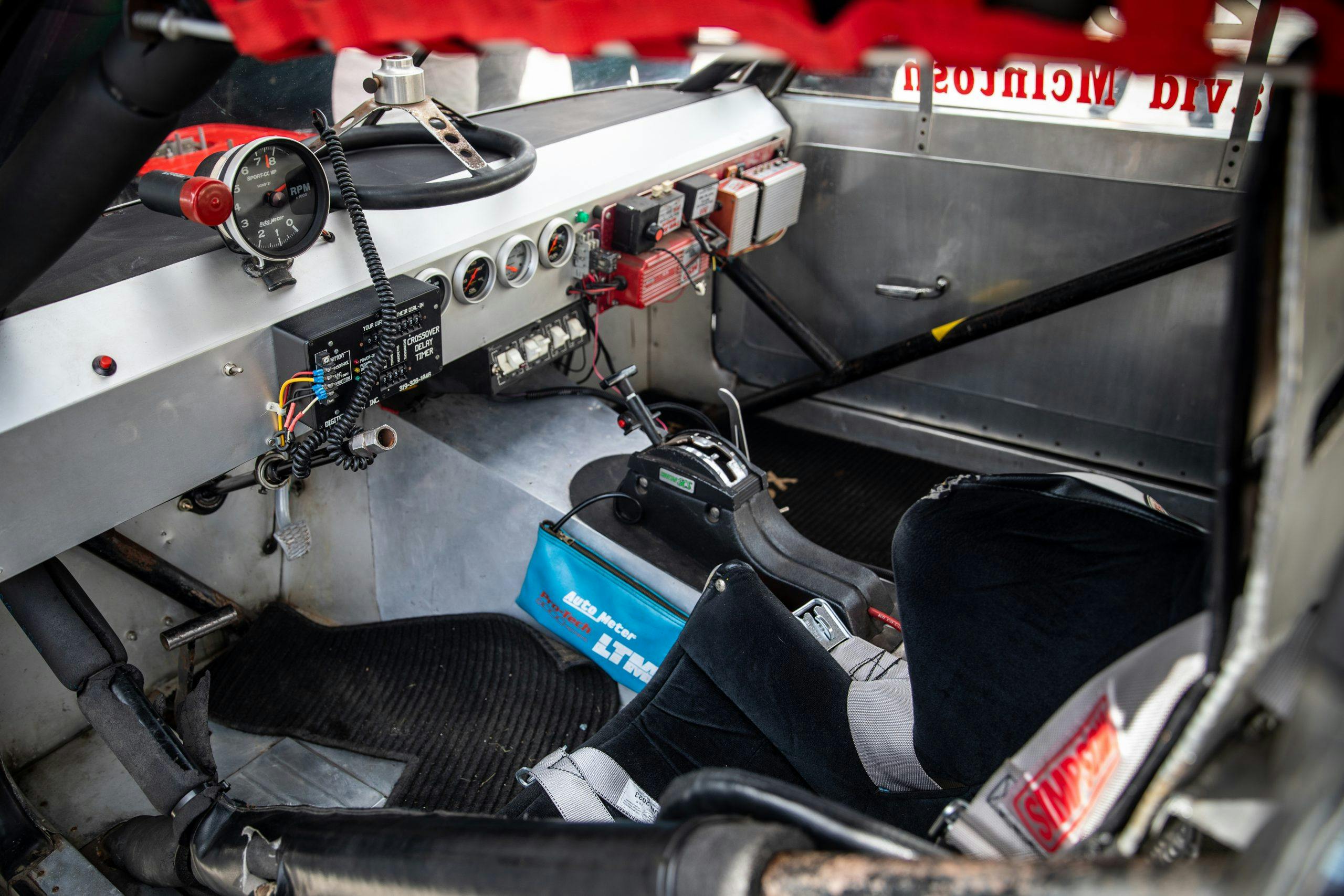

Of course, it wasn’t as simple as cleaning the car. No, it took three months for McIntosh and crew to prep the car that last drag raced 25 years ago. His buddy Eldon Glatfelter, who he met one year at the Nationals, made a 14-hour trip from Pennsylvania, and joined the project with friend Wayne Karraker, to help breathe life back into the old drag machine. McIntosh’s son Donald joined the fray too, equipping the car with a Motion Control Systems (MCS) shock package. An employee at MCS, and a racer in his own right, the young McIntosh actually built and designed the shocks for his father’s car.

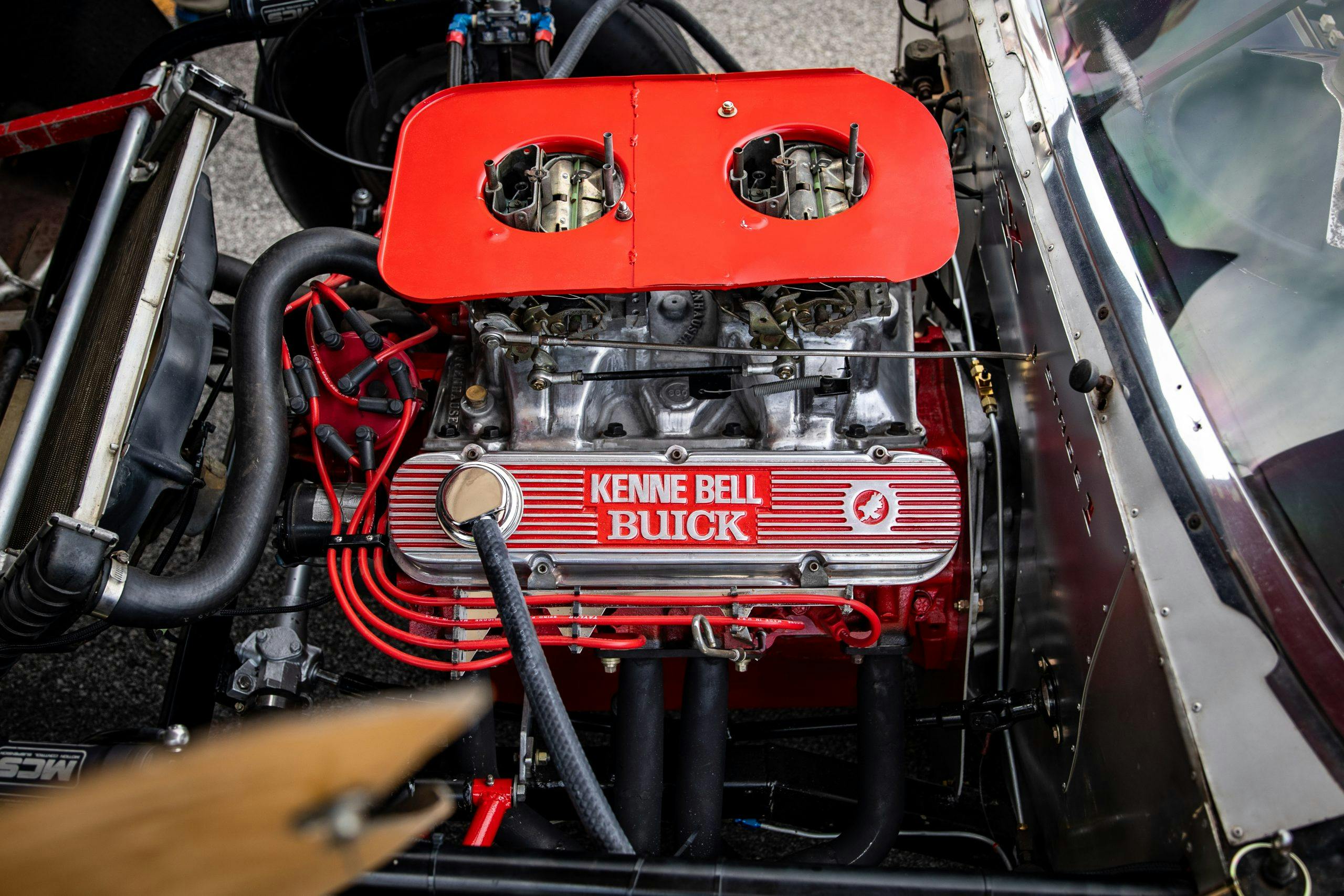

McIntosh’s band of merry men spent three months thrashing, vetting each component of the car. They went through the 455-cubic-inch engine, yanked back-in-the-day from a 1970 Buick Electra, and sat it under a new set of Stage one heads. An Offenhauser intake sourced from McIntosh’s old hot rod Corvair sits between the heads and is an example of McIntosh’s contrarian attitude. “Everybody told me the intake didn’t work,” he says. “That’s the reason why it’s on there.” The car was buttoned up just in time for the 2021 event, and by the first day of passes down the strip, the car sat ready in the pits. “It was an emotional rollercoaster getting there,” says McIntosh, who, in addition to the flurry of reviving the car, also had to navigate a mid-summer scare of short fuel supply.

Sporting the same fire suit he wore in 1992, the 65-year-old-racer made several passes down the strip, but not without mechanical gremlins. The first day, an aftermarket master cylinder failed and at the end of the strip, brake pedal met floor. Crisis averted, the team was able to make the repair. During his time in the box, though, McIntosh noticed he couldn’t heat the tires like he used to, nor could he leave from the Christmas tree drag light like he remembered. A broken torque converter was finally identified as the culprit.

Despite the issues, McIntosh was able to lay down a 9.75-second elapsed time and qualify for the “Quick 16.” “It’s a pretty big rush. I build a lot of street hot rods that have more power, but the street’s different. They don’t leave like that,” he says. “Plus, I’m old.”

McIntosh’s first-round competitor played games with the wily veteran, at one pointing balking and backing out of the staging box. With the benefit of some time elapsed after the race itself, McIntosh now considers the trickery a kind of compliment—his rival racer no doubt intimidated by the gold Buick’s reputation. Not to mention that the gentleman that knocked him out in the first round also went on to win the whole event.

“If you’re going to lose, you always want that,” says McIntosh. “I don’t know why you want that, but at least you don’t look as bad.” Results aside, McIntosh and his gold GS did anything but.

It’s stories like McIntosh’s the highlight the importance of these hot rod gatherings, from Goodguys in Ohio to the Ford Nationals in Pennsylvania, to the Grand National Roadster show in California. They till the automotive anecdotes to the top and kick camaraderie into overdrive. Even before the event, McIntosh’s friends and family united to prep the Buick. Yes, the vehicles are amazing, and the racing is great, but the mass car shows like these dotting the continent are in many ways family reunions thinly veiled in burnt rubber and vaporized high-octane.

“I got to see people I hadn’t seen in years,” says McIntosh, who was still remembered as a local legend by fans that attended the event in 1992. “Overall, if I had to do it all over again, knowing what I know now, I’d [still] do it,” says McIntosh, who had one last one-liner cued up. “Of course, I’d throw a new torque converter in first.”