The Long Haul, Part 1: What drives endurance drag racers?

Despite stereotypes of the racing world, drivers are rarely motivated by competitiveness alone. When you spend time around endurance drag racing at grueling events such as the 1300-mile Rocky Mountain Race Week (RMRW) 2.0, you’ll find characters motivated by technical achievement and others by wholly personal goals. There will always be heavy hitters looking to make a statement by winning the whole shebang, but between the headlines are deeply personal examples of human perseverance.

Emily Reeves

“I’ve had Roxy since I was 18,” says Emily Reeves. “When you drive something that long, you feel like you just know it, and you think that it’s predictable.” Roxy is a Pulse Red 2005 Pontiac GTO that’s been around for most of Emily’s life and became the foundation of a YouTube series starring Emily and her husband Aaron and known as Flying Sparks Garage.

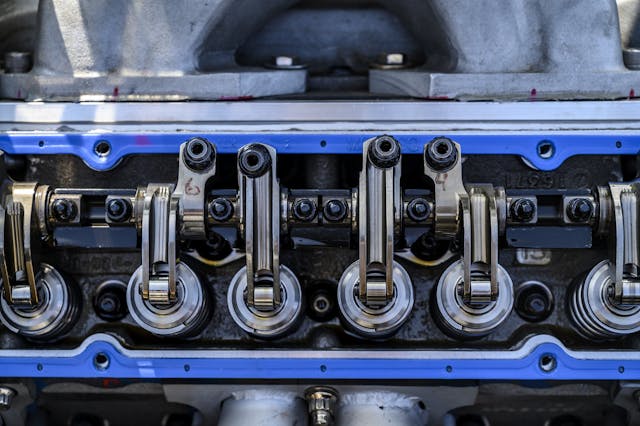

Though Roxy does duty as a daily driver, the car has evolved into a fire-breather thanks to a 408 stroker topped with a Magnuson TVS 2300 supercharger. Emily and Aaron built the engine with a forged bottom end that’s fed by PRC 227-cc heads and a lumpy COMP camp. The biggest upgrade for 2020 was a new six-speed manual built by Tick Performance—specifically, its Super Magnum, which stuffs the beefy guts of the TR6060 into the GTO’s original T-56 case. Together with a Mantic ceramic twin-disc clutch, the combo results in one potent street car. That rapid-fire power is sent through a Strange center section that adapts the beefy Ford 9-inch carrier for the GTO’s independent rear suspension, backed by G-Force axles.

Days before leaving for RMRW 2.0, Emily had a mysterious mechanical fault that, even after 15 years of owning Roxy, confounded her. “I was out test-driving the car with the new transmission when it just decided to stop,” she says. “It felt like I had dropped it into first gear!”

After coasting on the throttle, the car decelerated rapidly, sending everything she had sitting on the passenger seat crashing into the floor board. “I got out of the car and looked all over for tire marks or any clues as to what happened.” Nothing was obvious, and she called Aaron to tow the car back home.

Committed as ever, the couple boxed Roxy into the trailer before departing for the first day of racing. However, when she put the car on a lift and still couldn’t diagnose the issue, Emily grew wary of running her GTO that week.

“Having something scary like that happen on the car—I have to creep back into trusting everything,” she says. If the sudden deceleration happened on track, it wasn’t just her safety at stake, but that of the racer in the next lane. Other racers joked that the roll cage was there for a reason, but to Emily, Roxy wasn’t just a disposable race car.

Her first pass was soft; Emily simply focused on getting a good 60-foot time to get reacquainted with the car, lifting after the end of second gear to evaluate how the car felt after its enigmatic freeway ordeal. Consensus in the racing family held that a synchro in the transmission bound up on accident, with its clutch on the gearset slowing the vehicle down, but that WAG was only a hypothesis. Emily made a second pass, lifting once again after second, with no repeat of the freak fault.

“I had to get out of my head the visualizations of ‘what if I don’t react fast enough?’ or ‘what if it happens again at 120 mph?'” Emily says. “I had to focus on me being my best, and the car being its best, and let that prevail in my thought process. It was just kinda getting back in the car and talking to it. ‘Okay Roxy, I’m going to take care of you and you’re going to take care of me, and we’re going to do this. We’re gonna have fun.’ And we did—it was good!”

From then on, it was game on. Emily and Roxy immediately broke into the 11s and maintained that time all week. Each pass and each street mile rebuilt Emily’s confidence, and, with Aaron co-driving and helping with race and street prep, she could put maximum attention to her driving. “I hadn’t drag raced since Hot Rod Drag Week last year, so I had to relearn,” she says. Emily proved herself more than up to the challenge; at Thunder Valley, Roxy laid out its best ET and trap speed ever: an 11.262-second run at 123 mph.

Under the pressure of competition, people tend to discover more about themselves than they’ll understand in a lifetime. “Persevering through difficulties and challenges and overcoming them—I think that’s where the addiction lies,” says Emily. “Whenever you persevere and push through something that seems impossible and get through the other side of it, you want to do it again, because you feel like a complete badass.”

Mitchell Stapleton

Many projects reflect their owners’ own trajectory in life, but few drag racers and their machines have shared a path more intertwined than Stapleton and his ’13 Cadillac “LSXcalade.” First entered into Hot Rod Drag Week 2016 as a near-stock hand-me-down with an LSA blower strapped to the block, the LSXcalade became a rolling racing operation for Stapleton and his co-driver. The mission was conducted secretly, under the nose of Stapleton’s father, who had handed down the luxury SUV on the sole condition that his son not mess with it—but the secret didn’t stay under wraps for long.

His corporate communication classes at Penn State couldn’t keep Stapleton and the LSXcalade from Drag Week in 2016. To save money, he and his co-driver lived out of the SUV; his buddy built a bed on the roof while Stapleton slept inside. Stapleton even sold the factory wheels off the truck to pay for a set of slicks. The supercharged factory motor and 6L80E transmission were good for high-to-mid 11-second runs by the end of the week, but he wanted more.

“It was always fast for what it was, but it was still slower than everyone else,” Stapleton says. He set out a plan to build the whole truck for 10-second runs. A chance encounter at the Performance Racing Industry (PRI) trade show in Indianapolis got the ball rolling; Stapleton got the discount of a lifetime on a 427-cubic-inch LSX block (an aftermarket reinforced version of the LS architecture). By the time he left Indy to head back home to Pittsburgh, he had worked out partners and a grocery list of pieces for his 10-second goal.

Stapleton loaned shop space from a friend and set up digs in an enclosed trailer next door. For months, he spent his free time fabricating instead of studying or bar-hopping, and the LSXcalade emerged wearing twin 76-mm Precision turbos that fed boost to a Holley Hi-Ram. The turbo’s hot- and cold-side piping was Stapleton’s first kit build. “When I started this, I had no idea how to weld a turbo kit,” he says.

That year, Stapleton’s hobby turned into a full-time career. He had already built a cult following on Instagram thanks to the SUV’s freak-show appearances at various street car events, and he began to share his adventures and projects on YouTube. With each video, he discovered he had more and more in common with his drag-racing, engine-building audience.

“I dropped out of college in January—it just kept falling further down my list of priorities each day,” he says. “I already had enough momentum, and my family could deal with it however they wanted to. But if I was going to quit college, I was going to spend all that time I would be in school on YouTube to make it work.”

That’s exactly what he did. His channel, Stapleton42, provides an honest look at a barn-storming drag-racing build and the sacrifices such a project requires for the average builder. He may give up a comfortable lifestyle and a typical social life, but Stapleton collects irreplaceable memories and earns a sleeper build that continues to smash each goal he sets.

One such shattered goal? That 10-second barrier, which fell on the final day of RMRW 2.0 with a rowdy 9.42-second final pass, a personal best that crushed the double-digit ET goals Stapleton had set a few short years ago. The straight-line monster sank into single digits shorn of its hood, one down-pipe hacked and re-welded into a stack after the exhaust broke below the SUV the day before. Its mid-pack finish in the Limited Street class was irrelevant; Race Week 2.0 had validated five years of blood, toil, tears, and sweat.

“People will often cap themselves,” says Stapleton. “I mean, that’s crazy. If I never sat daydreaming in class, thinking, ‘Y’know, I bet I can put 2000 horsepower in my Escalade,’ that would have never happened. I had to build it in my head before I could build it for real, and many people don’t know how powerful it is to regulate their own thinking.

“It’s no different than pulling up a data log of your tune so you can change stuff to make it better. Look at yourself—why you do things and how you’re doing them, what are your habits … that kind of stuff.”

Robert Williams

Perseverance is a term that gets tossed around often, but few environments bring out this quality like racing does. You can feel alone while all eyes are on you, watching for a great comeback.

Even when there may be no financial fruit of their labor, the simple intent to see something through to the end keeps a racer running, no matter how destructive or abysmal the situation may look. For Robert Williams and his “Weapon X” ’77 Chevy Nova, perseverance looks like three destroyed engines, of which only one survived to the end of a hellish week—and just barely kept its bottom end from scattering until it completed the event after a safe pass on day five.

“Weapon X” is an X-body Nova, the last of the traditional GM-engineered compacts before the nameplate was loosely affixed (many times, literally—the badges frequently peeled off) to the AE82 Toyota Corolla. Any sign of the Malaise Era Chevy’s roots are gone in Weapon X’s current form, thanks to a turbo 6.0-liter LY6 “truck LS” and a heap of goodies underneath. ARP main studs clamp down on Trick Flow 225-cc heads, which are fed by a Holley Lo-Ram intake with a Shearer Fab intercooler sandwiched between the upper and lower plenum halves. The home-brew LS combo flirts with four-digit horsepower and is bolted up to a Transmission Specialties-built TH400. A 35-spline Ford 9-inch backs up the driveline with 3.25 gears on a spool. All of that chaos is suspended by QA1 tubular front A-arms with DA coil-overs and split Calvert mono-leafs with Caltracs in back dampened by AFCO shocks.

You know what they say about the best-laid plans, though.

“It’s the car that’s never failed to fail,” Robert jokes with a jaded laugh. With two previous Hot Rod Drag Weeks ending early with dead motors, his goal for 2020’s Rocky Mountain event was simply to finish. Together with his son David, who doubled as his co-driver, Robert set out with modest hopes, only to have the head torch itself on the first run. “I saw it chuff a bunch of water out during the run, and knew that it had pushed a head gasket,” Robert recalls.

As the head gasket fails, combustion gasses will typically pressurize the coolant system as the gasket breaks down at its thinnest points near the water jackets. With the addition of boost, the escaped combustion gas essentially turns into a high-pressure torch, melting a channel through the motor as it escapes into the atmosphere. To say that Robert was frustrated is an understatement, but his son wouldn’t let him quit on the first day.

David wouldn’t let his father quit on the second day, either—or the third, or the fourth. The local Tulsa racing community held them get the aluminum head TIG-welded and decked, but Weapon X continued to fight them throughout the week. Still, the Williams boys kept hacking at each issue day by day, from lost trunk keys to leaking coolant steam-vent lines, battling exhaustion and stress as the days grew longer and the nights grew shorter. “I felt like we were playing catch-up all week,” Robert said.

As luck would have it, so was his competition. In the red mist of repair, Robert was hardly focused on the standings in the Outlaw Street class, figuring there was no chance to make the podium. Their pass on day two was a soft 16-second run simply to get it down the track without drama. As each day dawned, however, they began to find the speed they expected from Weapon X. They clawed into the low 9s on day three before breaking the 8-second barrier with a 8.927-second pass at Great Bend, only to be pushed back from the line several times with a tricky water leak.

By Friday, Robert was just pleased to be driving into Tulsa Raceway Park under his own power. There wasn’t much else to do but to make a final pass to seal the week, and their 9.015-second run did just that. As the staging lanes dwindled down at the end of racing on day five, they made one more run to see what the car would do now that conserving the motor was no longer a concern. Ever true to form, Weapon X scattered another bottom end during the pass, oiling down the track and closing the right lane. Robert was disappointed and apologized on the Rocky Mountain Race Week Facebook group for oiling down the lane. After pushing Weapon X onto the trailer, he found chairs for himself and his son at the awards ceremony.

Much to his and David’s surprise, Matt Frost called Robert’s name for third-place trophy in Outlaw Street. Despite near-daily struggles, the pair’s grit inadvertently paid off. “I didn’t even know I had placed in the class—I was blown away,” Robert says.

Jason Tabscott

Few situations hurt car folks more than theft. Years of split knuckles, hard-earned cash, and late nights can be lost to greed, usually for the build to be sold piecemeal on the black market. For Jason Tabscott and his family, however, the loss of their 1975 Chevrolet Camaro indirectly led to meteoric success in 2020 with a new naturally-aspirated small-block record in RMRW 2.0.

Like most folks, Tabscott packed away his wrenches when life and family took over. Tabscott fell in love with endurance drag racing a decade prior when Hot Rod magazine launched its first Drag Week in 2005, “This is me! David Freiburger invented a race where I fit in!” he exclaimed. Before there were events like it, Jason just dug the challenge of driving to an event, racing it, and driving home, “I always looked up to the street-driven race car, and had animosity for the bracket race car that could only bracket race. I would build pro-touring cars in the eighties — build a hot rod engine, but focus on the suspension and chassis. And then I got into drag racing, but I always made sure my car drove.” But building a family took eventually priority over building the ultimate street car. As the years went on, and as the kids grew up, he returned to the Camaro. Before too long, the ’75 was ready for Drag Week 2015—and promptly stolen afterwards.

The new car, a ’70, arrived after an exhausting search for a clean second-gen Camaro. It was pricey, but thankfully, the rowdy big-block under the hood was worth its own chunk of change. Out came the big-block and in went a 427-cubic-inch Dart Iron Eagle small-block, the foundation of Tabscott’s build. Callies supplied the rods and crank, and Diamond pistons worked with the Dart 15-degree heads (ported by BES) to run compression at a “you can’t do that” level in the mid-teens. (The exact number is a part of the secret sauce.) Tabscott spent the bulk of his time on the valvetrain, using 0.650-inch T&D shaft-mounted offset rockers to relocate the 7/16th Manton upright to improve the valvetrain geometry for 9000 rpm.

This year, the motor’s power curve was shifted up via a new cam with longer duration, which culminated in this year’s ground-breaking performance. After the 8-inch Ultimate Converter Concepts 7500-stall unit, power is split by a Turbo-400 with a Gear Vendors overdrive hung off the tail, which splits gears ahead of the 4.30 rear end, a Strange 9-inch unit that spins 40-spline axles gun-drilled for less weight. Things are more conventional when it comes to the chassis. TRZ tubular suspension bits up front complement the Caltrac bars and monoleafs in the rear, and all four corners are dampened by Santhuff shocks.

The product of third-shift shuffles and late weekend nights, the new Camaro entered Drag Week 2016 to win the Street Race Small-Block NA class, a feat that it replicate four years in a row, pushing its average time deeper into the 9s each week.

“We didn’t have any real problems all week,” says the four-time Drag Week class champion of the 2020 Rocky Mountain event. His wife, Amanda, co-drove the Camaro and their buddy Robert McGinness tagged along, too, so there were plenty of hands on deck for the race-prep each day.

Oklahoma’s Thunder Valley brought the stiction at the light, grazing the eight-second barrier on Day Three with a 9.014. After making their last safe run on day five, the team switched into “go big or go home” mode. The team installed a new converter with a smaller diameter, which was tighter in the mid-range and got the revs up into the new cam’s higher powerband thanks to its high stall. With these two big changes, Tabscott let the Camaro sing at 9000 rpm before shifting, which set him up for the 8.997 blast that finally broke the 9-second barrier. Thanks to the car’s consistently low ETs, RMRW 2.0’s NA Small-Block class was a sure victory for Tabscott, and breaking into the eights was the perfect bonus to a good week of racing.

This is the first in a two-part series. Stay tuned for the stories of five more racers and their builds from Rocky Mountain Race Week 2.0.