Talladega and Zora: The untold saga of Yugo’s endurance record attempt

Few OEMs can resist the allure of the record book. Not all records are created equal, of course: Compare Porsche’s 19 Le Mans wins with Jaguar’s Guinness-approved seven Hot Wheels loop-the-loops. Despite the disparity in glory, any track-related “record” is laden with marketing potential. Every automaker wants a place in the history books—even Yugo.

In 1988, the Eastern Bloc automaker—via its Yugo America importer—embarked upon an ambitious attempt to set a number of endurance records at Alabama’s Talledega Superspeedway. Spearheading the project was none other than the legendary Zora Arkus-Duntov, revered as the godfather of the Corvette.

Unfortunately, while a pair of track-prepared Yugos did make it to Alabama in October 1988, they never turned a wheel on the track. The Yugo was seemingly destined to hold a single, uncontested title: The Worst Car Ever Made.

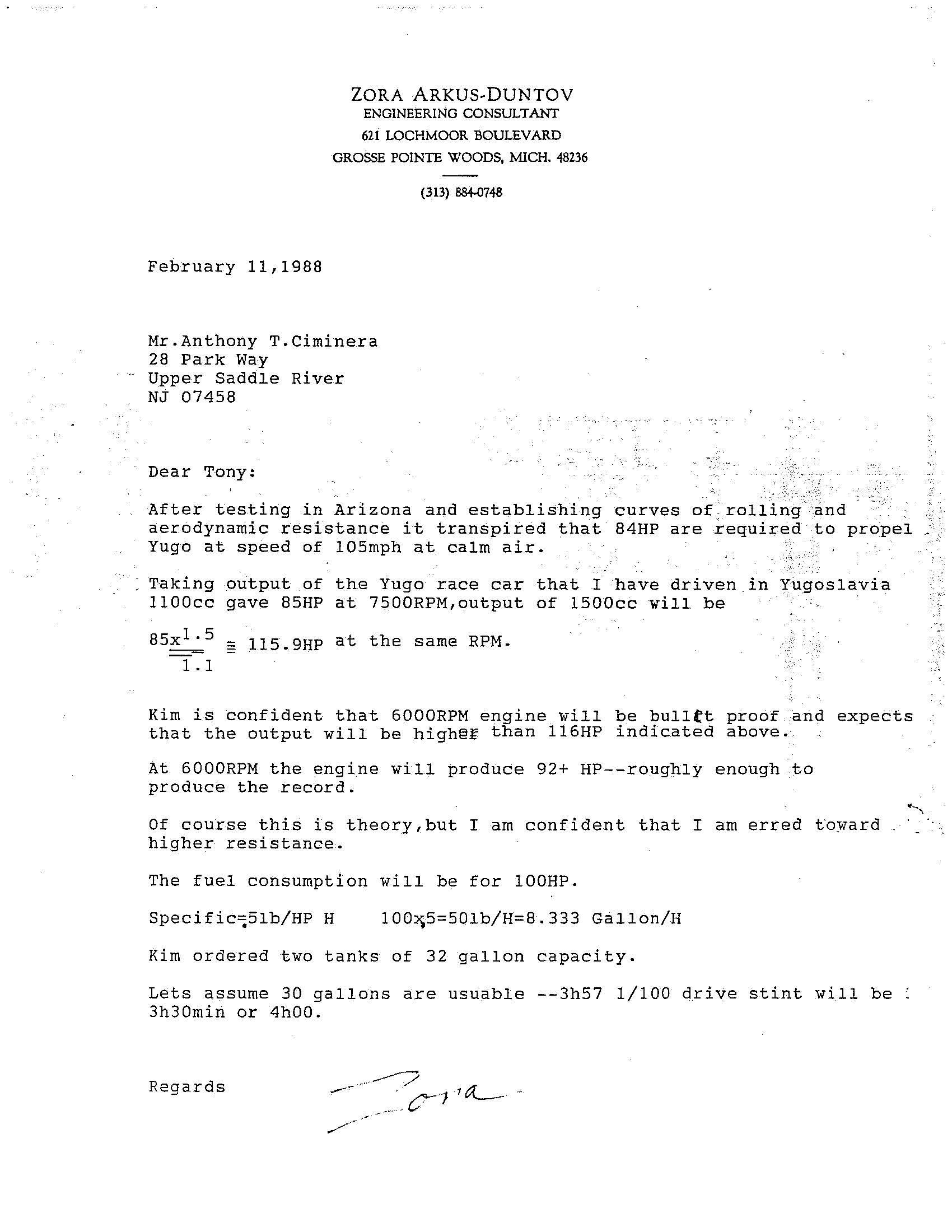

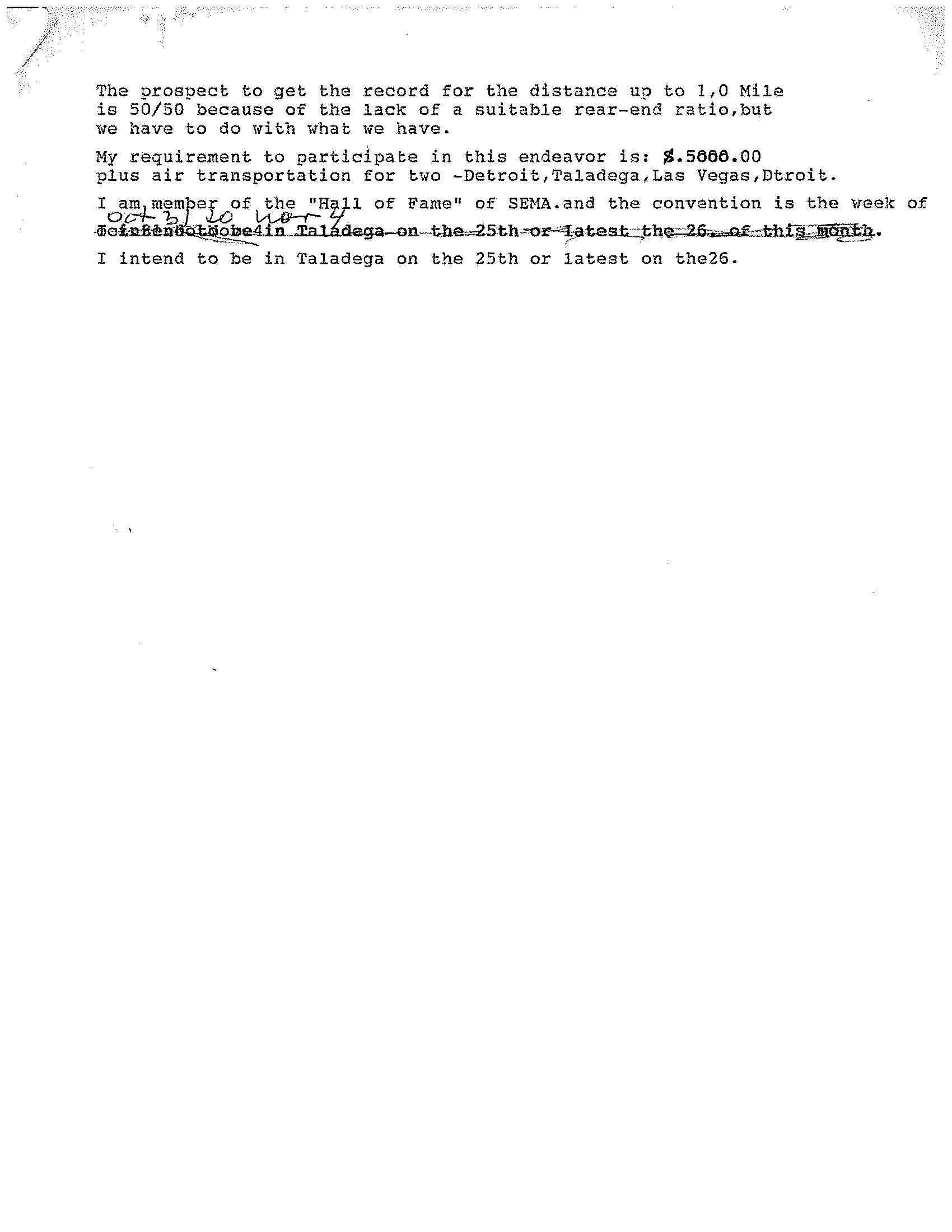

While researching an unrelated project at the GM Heritage Center near Detroit, your author was handed a sheaf of seemingly misfiled documents. Within was a trove of Duntov’s personal correspondence—including a number of papers bearing his personal letterhead and dated after his retirement from GM in 1975. A pair of letters, reproduced here with the permission of General Motors, stood out.

Zora the Engineer

Before coming to GM in the ’50s, Zora Arkus-Duntov and his brother Yura started Ardun Mechanical Corporation, a company that became famous for the replacement hemispherical cylinder heads it offered for Ford’s flathead V-8. Zora later worked for the British Allard Motor Car Company, even driving for the factory team at Le Mans. Though he joined General Motors as an assistant staff engineer in May of 1953, Zora returned to the Circuit de la Sarthe in 1954, this time with Porsche, and drove his 550 Spyder to a class victory. Back in the states, he built the legacy for which he is best remembered: forging the Corvette into a performance car.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Once he moved on from GM in ’75, Zora continued with his engineering consulting work. He developed performance intake manifolds for Holley through the ’80s. Later, he was contracted by Global Motors (the parent company of Yugo America) via its enigmatic leader, Malcolm Bricklin, to help develop the Yugo’s performance image.

One thing stands out about Zora—his intense curiosity. In his quest for speed, he relentless tinkered and tweaked whatever vehicle in which he found himself. Tony Ciminera, then Yugo America’s senior vice president of production and engineering, says that Zora once wanted to set an aviation speed record with a home-built airplane. He intended to use the Suzuki three-cylinder engine from the Chevrolet Sprint/Geo Metro—but his wife would have none of it. Ciminera says that she “told GM to make excuses so he couldn’t get an engine.”

Zora was the one who decided on a Yugo endurance record attempt. According to Jerry Burton’s biography of Arkus-Duntov (Zora Arkus-Duntov: The Legend behind Corvette, Bentley, 2002), Bricklin and Ciminera originally planned a single-marque road-racing series in the vein of the Corvette Challenge. Then Zora, after poring through the FIA record books, found a number of records that sounded easy to conquer.

Bricklin had little to do with the record attempt. In a brief interview, Bricklin told us “that was Zora and Tony [Ciminera]’s pet project.” And if the timeline of Yugo’s corporate machinations is correct in Jason Vuic’s excellent The Yugo: The Rise and Fall of the Worst Car in History, Bricklin would have been mostly out of the loop by this time, since he was bought out in March 1988 by an investment firm (though he stuck around as a consultant).

Why Talladega?

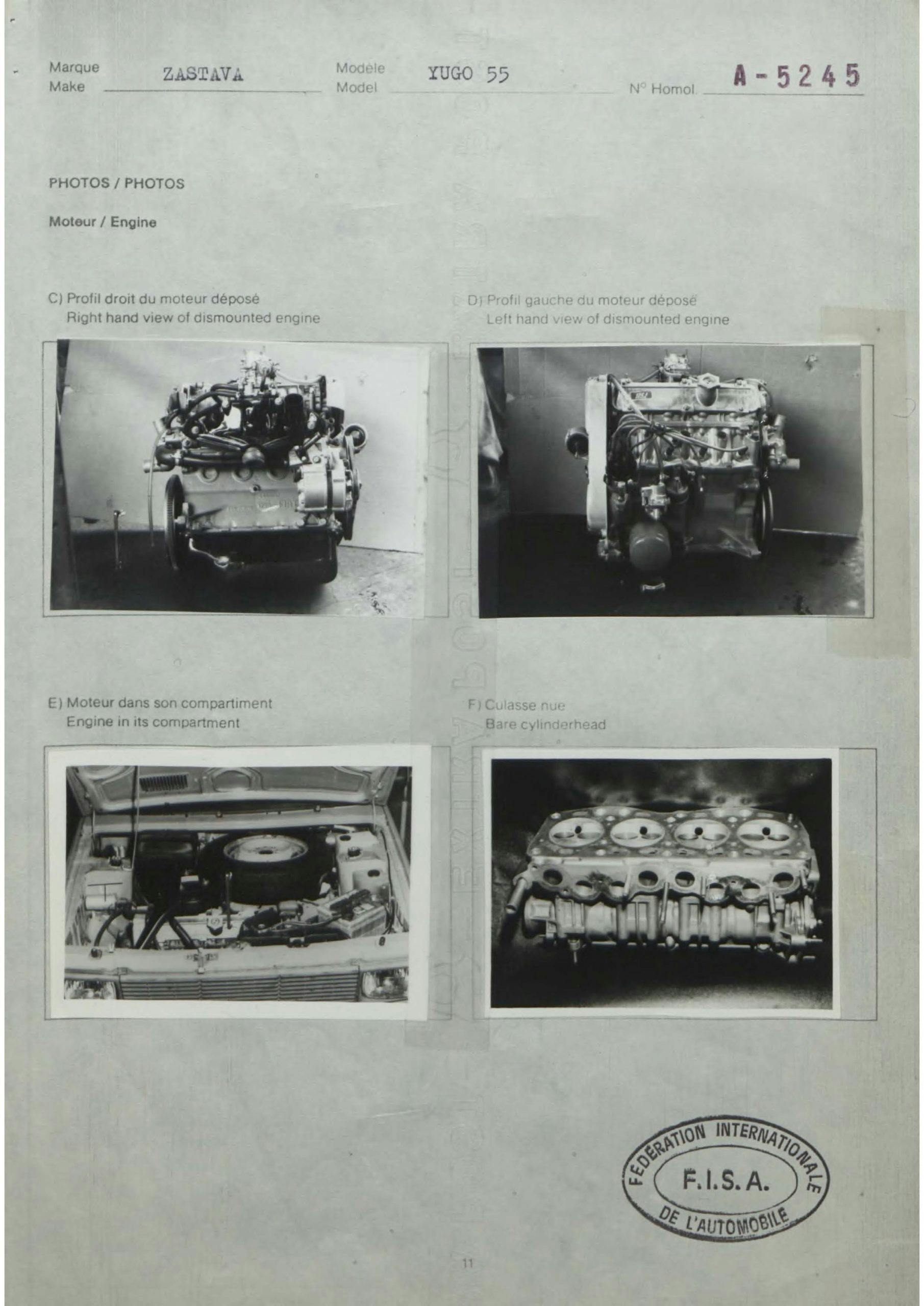

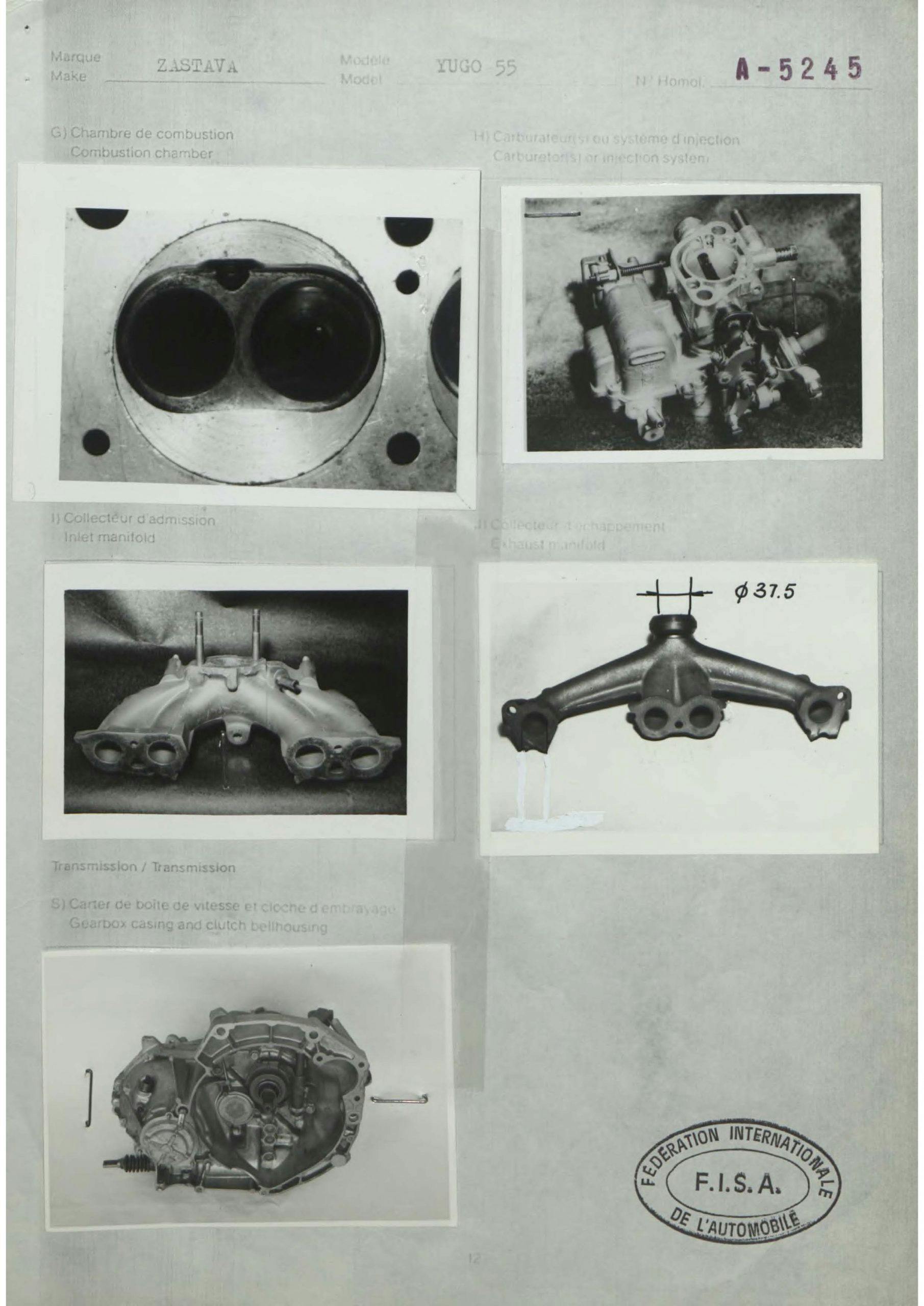

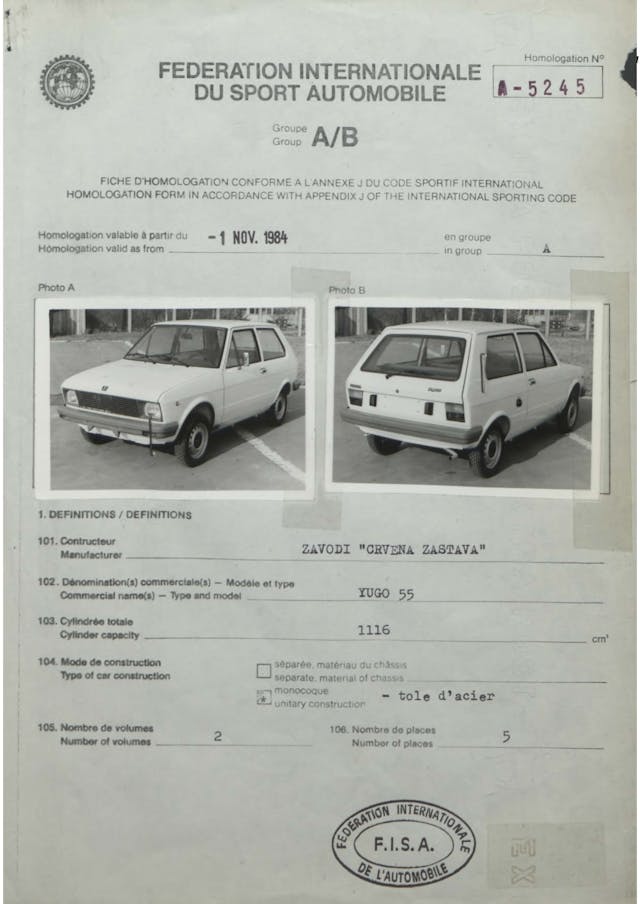

Duntov noticed that the Yugo would fit into the FIA Category A, Group II, Class 6 for endurance (or speed) records. Group II was restricted to naturally-aspirated Otto-cycle engines; Class 6 included engines over 1100 cc but under 1500 cc. The records that existed had been established on July 31, 1981 at the Bonneville Salt Flats by Larry Wilcox and his Mercury LN7, the upmarket version of the Ford EXP. A glance at the FIA record book shows that the records stand to this day. (For fans of campy ’70s TV, the name Larry Wilcox might ring a bell. Yes, he was the actor who played Jon Baker on CHiPs.)

Zora scoured the records for a challenge that would suit the Yugo’s, er, peculiar strengths. The flying mile and standing kilometer were the two longest records in the Yugo’s class, making long-distance records ripe for the taking. Zora settled on an endurance test held on an oval track.

The Cars

Ciminera enlisted Massachusetts racer Kim Baker to build a pair of Yugos—one red, one blue—for a 24-hour run around Talladega. Baker is likely best known for his success racing C4 Corvettes in various endurance racing series, but prior that effort, he ran a Fiat X1/9 in SCCA competition—with occasional help from Fiat’s importer, International Automobile Importers (IAI). (At the time, Ciminera was the VP of IAI.) Since the Yugo was a licensed development of the Fiat 127 and 128—the ancestors of the X1/9—Baker was the Yugo’s last best hope to get in the record books.

Baker tells us that his modifications to the pair of Yugos were minimal and focused on reliability rather than on speed. The cars were based on the Yugo GVX, which started with a larger, 1300-cc engine and a five-speed manual transmission. Baker modifying the transmission with a straight-cut fifth gear that lessened friction and added much-needed strength to the Fiat-based transaxle. Both cars were fitted with 32-gallon fuel sells and filler necks on both sides so a pair of crew members with dump cans could quickly refuel each during a long run.

To minimize attitude change over long runs, Baker moved the fuel cells well forward of their usual location. Belly pans helped smooth airflow underneath the Yugo, and the wheels were pushed outboard. A smaller radiator was fitted; the engine required just a third of the airflow through the radiator compared to stock, so the fascia could be closed off for improved aerodynamics. Baker mounted the exhaust to run nearly flush with the belly pan.

Since little braking was needed on Talladega’s 2.66-mile oval, Baker actually downgraded the stopping system to save weight, using lighter discs and drums along with smaller pads and shoes. He installed a device to retract the pads further to minimize drag and chose larger-diameter wheel bearings to minimize friction losses. In the place of suspension bushings, he used bearings designed to keep the wheels at both zero camber and zero toe—again, to lower drag. Baker even conducted coast-down tests at a local airport to verify the Yugo’s increased slipperiness.

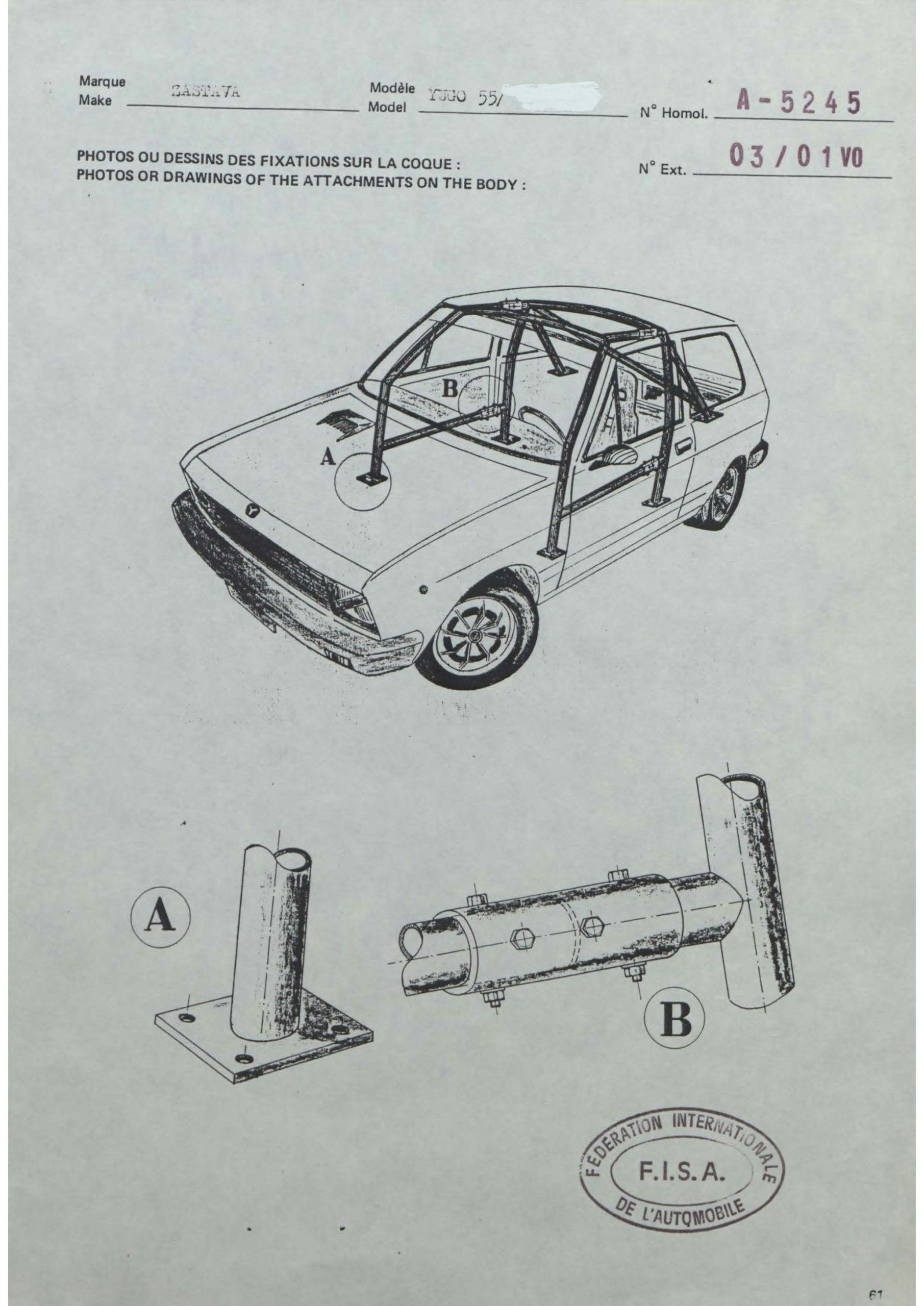

A minimal roll cage was fabricated to protect the drivers, and all glass other than the windscreen was replaced by plastic. Since the speed at which they’d be hitting Talladega’s banks would not generate an extreme lateral load, Baker fitted the Yugos with low rolling-resistance tires. He even implemented a trick he learned in his endurance-racing Vettes to reduce tire-change times: coarse-threaded wheel studs.

Baker gave each car’s engine a displacement bump to just under the class limit of 1500 cc plus, as he puts is, “the usual race mods.” Interestingly, he swapped each car’s factory fuel-injection system with a pair of Weber carburetors. Sure, the carbs were easier to tune than ’80s-era fuel injectors—especially for a long run at steady rpm—but Baker had a more practical concern. The Webers were cheaper.

Yugo America never actually paid Kim Baker for his work, though the company let him take possession of the cars. The whereabouts of the two Yugos are now a mystery—if anyone knows of a caged Yugo with some odd mods laying around, please leave a note in the comments! Baker thinks the cars were scrapped, though we’d guess that the powertrains ended up in Fiat club race cars somewhere.

Alabama, October 1988

Why haven’t we heard about these record attempts? Certainly the late-night comics that skewered Yugos and Yugo drivers throughout the ’80s would have latched onto the novelty of a race-liveried GVX, right?

Well, the runs never happened.

Yugo America did rent the Talledega Superspeedway for a week in October 1988. Ciminera and Baker brought the cars south. But Yugo America pulled the plug while the cars were being unloaded.

“Duntov got the call at his hotel the night before the run,” writes Burton (374). “The cars never turned a wheel. ‘It was one of the most embarrassing moments of my life to tell Zora the program was off,’ said Ciminera.”

Why did Yugo stop the record attempt? There are two scenarios, both plausible—it’s likely some combination of both:

- Political unrest at home in Yugoslavia meant a highly publicized record attempt would look frivolous to a country still wrestling with Communism.

- Global Motors, the parent of Yugo America, was experiencing financial difficulties. The investment firm that bought Global Motors from Bricklin et al had expected a new product line to come to market via Proton of Malaysia, but that never happened (Vuic, 179).

With one phone call, the dream of a record vanished. Eleven years later, that factory itself vanished via NATO airstrike during the civil war that tore apart Serbia. The plant has since been retooled to build Fiats, including the 500L, though the factory’s future looks dark in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Compared to the Yugo, however, we’d like to think that even the 500L stands a chance at making the endurance record books. Any takers?