Legends of Motorsports: Hellé Nice

She was a gorgeous former model and dancer, paramour of some of the richest and most powerful men of her time. She set world speed records and raced against other legends such as Louis Chiron, Tazio Nuvolari, and Count Carlo Felice Trossi. But at the end of her life, she was so poor she was reduced to stealing the bowls of milk her neighbors had put out at night for their cats, and she died completely broke and utterly alone. Her name is Hellé Nice, and this is her story.

She was born Mariette Hélène Delangle on December 15, 1900, near Chartres, France, the daughter of the local postman. In 1916, she went to Paris where she initially found work as a nude model for artist René Carrère. Carrère encouraged the young woman to take up ballet, and she became quite successful, first dancing under the name Hélène Nice, which she later changed to Hellé Nice. Her career as a model and a dancer was successful enough to allow her to buy a house and a yacht.

One of her lovers was the racing driver Henri de Courcelles. De Courcelles introduced Nice to Europe’s great racing venues just as grand prix racing was sweeping across Europe. In 1921, Nice attempted to enter a race at Brooklands in England. When her application was rejected because she was a woman, she was furious. She raced when she could, but she was never allowed to compete on the strength of her talent and instead was excluded due to her gender. She turned to skiing to fuel her need for high-speed excitement; an injury she sustained in 1929 while outrunning an avalanche during a ski run put an end to her career as a dancer.

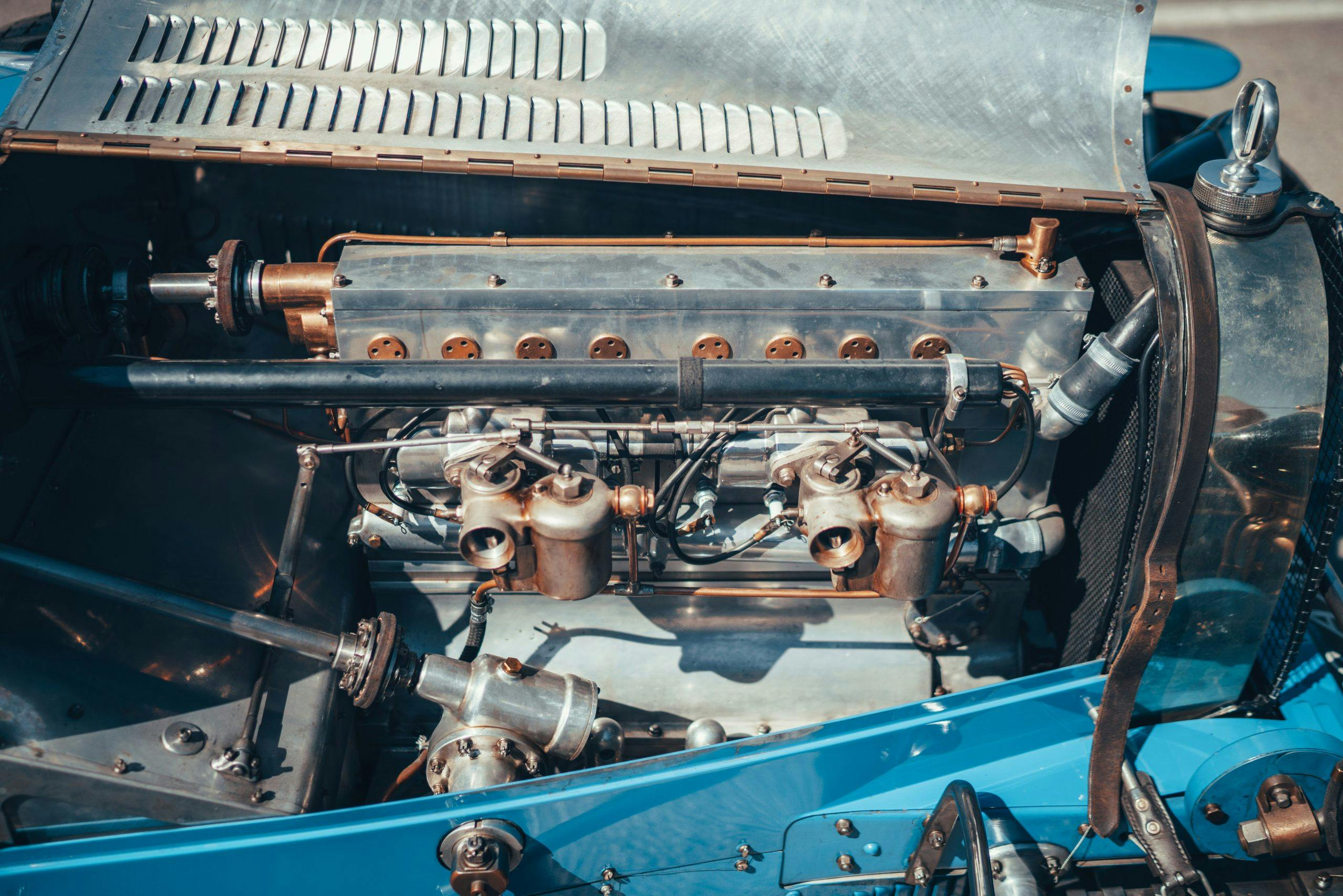

Nice turned to racing. She trained for and won the first Women’s Grand Prix held in June 1929, piloting an Omega 6 that was given to her by the manufacturer Jules Daubecq. Daubecq had been persuaded that photos of a glamorous female champion in one of his vehicles would help sell his cars. This grand prix was part of a weekend of female-only races held at Montlhéry, the first purpose-built racetrack in France. In December 1929, she drove a Bugatti Type 35C to a world record of 198 kilometers per hour (123 mph) over a 10-kilometer (6.2-mile) course, again at Montlhéry. “The driving was magnificent: nobody who saw it would feel able to argue that women drive less well than men,” stated the newspaper L’Intransigeant.

The French press dubbed her La Reine de Vitesse—the Queen of Speed. The day after her victory, Nice received a telegram from Bugatti asking her to drive for the factory. She immediately accepted the offer and won the Actors Championship in a Bugatti, succeeding in a major tournament in which men competed, too. In addition to the victories, Nice signed with Lucky Strike, the “cigarette of the championship winner,” and thousands of posters appeared featuring her visage. Within a few months, she became one of the most famous people in France.

In 1930, she traveled to the United States to race supercharged Miller cars on dirt tracks. At first, she was signed as a salaried exhibition driver, preferring to get behind the wheel without wearing a helmet because, she said, “the crowds always like to see my hair when I am driving.” She signed another lucrative advertising deal—this time with Esso—and was crowned “the Bugatti Queen” by the press. Rich and now famous worldwide, Nice returned to Europe, determined to make her mark as a grand prix driver. Her desire was rewarded in the season’s first grand prix, when she placed fourth racing against the sport’s best drivers, including Philippe Étancelin, René Dreyfus, and Louis Chiron. She competed on tracks across France and Italy, earning the equivalent of $100,000 in today’s dollars as an entry fee for each race.

In addition to racing fast cars throughout her career, Nice lived fast, too. As her renown increased, she found no shortage of lovers. Some of her affairs were brief; others were longer and included, beyond the wealthy and powerful Philippe de Rothschild (also a racer of grand prix cars in the era), members of the European nobility and other personalities such as the aforementioned Henri de Courcelles, Jean Bugatti, and Count Bruno d’Harcourt.

Despite her many successes, she never took first place in men’s races driving her Bugatti. While often the focus of attention wherever she raced, she was not the top female driver of the day; that honor went to Elizabeth Junek, who also raced a Bugatti. Regardless, Nice was without question a talented driver of cars that were dangerous and difficult to drive, regardless of who sat behind the wheel.

On September 10, 1933, then piloting an Alfa Romeo, Nice drove in one of the deadliest races in history. During that year’s Monza Grand Prix, three of the period’s leading race drivers—Giuseppe Campari, Baconin “Mario Umberto” Borzacchini, and the Polish count Stanislas Czaikowski—were killed. Nice placed third (and last of the finishers) in the race’s second heat, in which Campari and Borzacchini had been killed. She was flagged off in ninth place, two laps behind the winner, in the shortened final in which Czaikowski had died.

In 1936, she journeyed to Brazil to compete in two grand prix races. During the São Paulo Grand Prix, she was in third place behind Brazilian champion Manuel de Teffé when a freak accident almost ended in her death. Her Alfa Romeo pinwheeled through the air and smashed into the grandstand, killing six people and wounding more than thirty others. Nice was launched from the Alfa and she landed on a soldier, who bore the full impact of her body, saving her life. The impact killed the soldier and because Nice lay unconscious, she, too, was thought to be dead. Taken to the hospital, she was comatose for three days before regaining consciousness; two months later, she was discharged from the hospital.

As a result of the serious head injuries she had suffered, she was not able to convince a manufacturer to risk hiring her. In 1937, she attempted a comeback, hoping to race in the Mille Miglia and the Tripoli Grand Prix, both of which offered substantial purses. Unable to find backers, she instead entered endurance trials for female drivers, sponsored by the oil company Yacco. Nice teamed up with three other women at Montlhéry and alternated stints behind the wheel. Together, the women drove for 10 days and nights straight and broke 10 world records over distances and timespans ranging from 12,500 miles to 10 days. Still she was unable to secure financial backing.

Over the next two years, Nice drove in rallies and held out hope to be signed once more with the Bugatti team. But then came the double blow: Jean Bugatti, the son of company founder, Ettore, was killed tragically on August 11, 1939, while testing a Type 57 tank-bodied racer. Three weeks later, Germany invaded Poland, and the world was once more at war. France fell in late June 1940; in 1943, Nice moved to the French Riviera and set up with a lover in a sprawling estate overlooking the city of Nice. It was here that the pair spent the duration of the war.

Did she become an informant to land this swank residence on the French Riviera? Nice’s biographer, Miranda Seymour, does not arrive at a definitive conclusion on the issue. What is clear is that the mere appearance of the situation was sufficient to destroy any hopes Nice had of resuming her career in postwar Europe. In 1949 at a party in Monaco, her former racing adversary Chiron flung at her the accusation of “collaborating with the Nazis.” Despite a lack of proof, Chiron’s claim left her unemployable. Her family, too, believed the rumors and disowned her.

The final years of Nice’s life were a stark and bitter contrast to the first. Destitute and abandoned by her friends and family, she was forced to rely on meager handouts from an actors’ charity—the very type of charity she had helped to fund during the halcyon days of her youth as a showgirl. At age 75, Nice was reduced to moving into an attic in a run-down part of Nice. Her neighbors told biographer Seymour that they recalled seeing Nice “taking the milk out of the cats’ saucers because she had nothing to eat or drink.” She died eight years later on October 1, 1984, age 83.

Nice’s family refused to add her name to their memorial stone, and it took Seymour four attempts to finally locate Nice’s unmarked grave. A foundation was eventually established to establish a memorial plaque at her gravesite and continues its work to restore Nice’s reputation as one of the greatest drivers in history.