Hans Stuck Put in the Miles to Make the Porsche 962 the Winner It Was

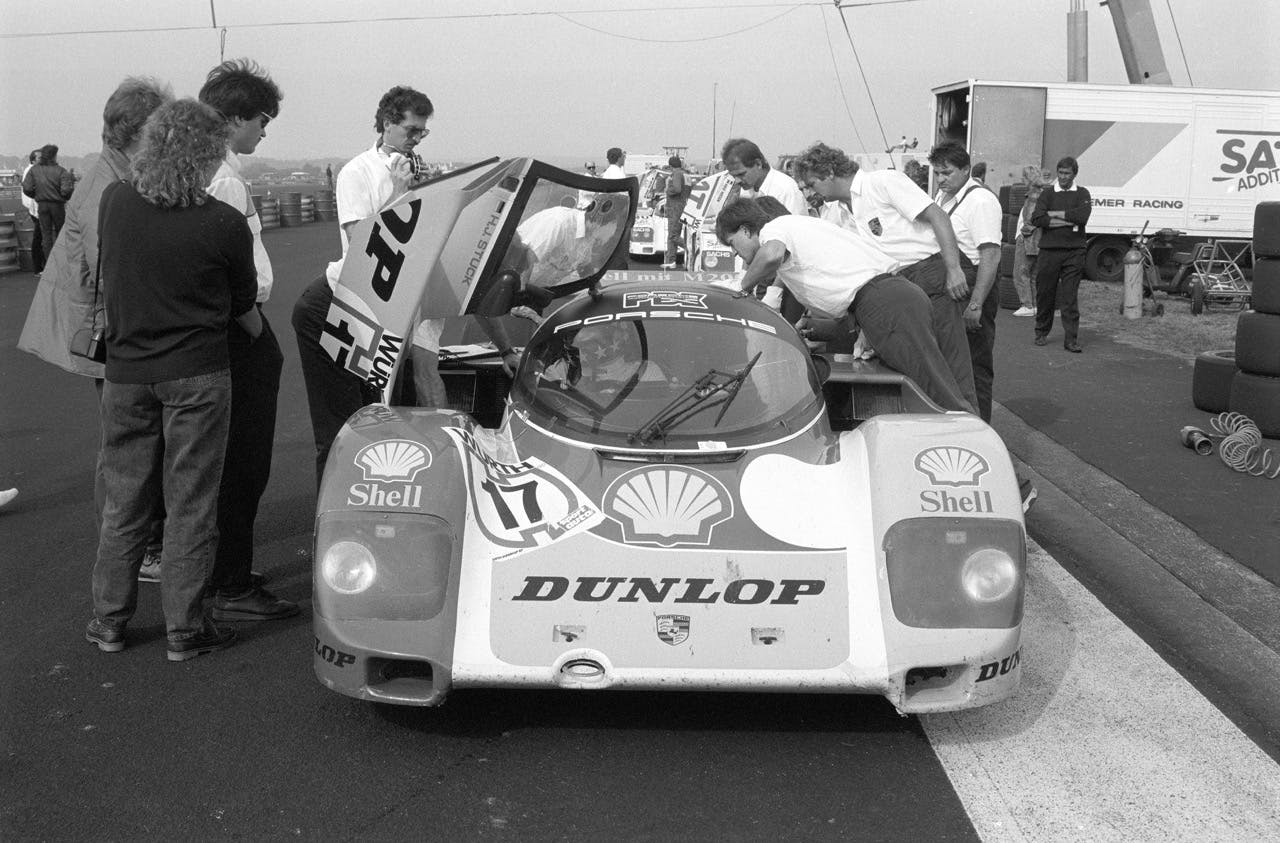

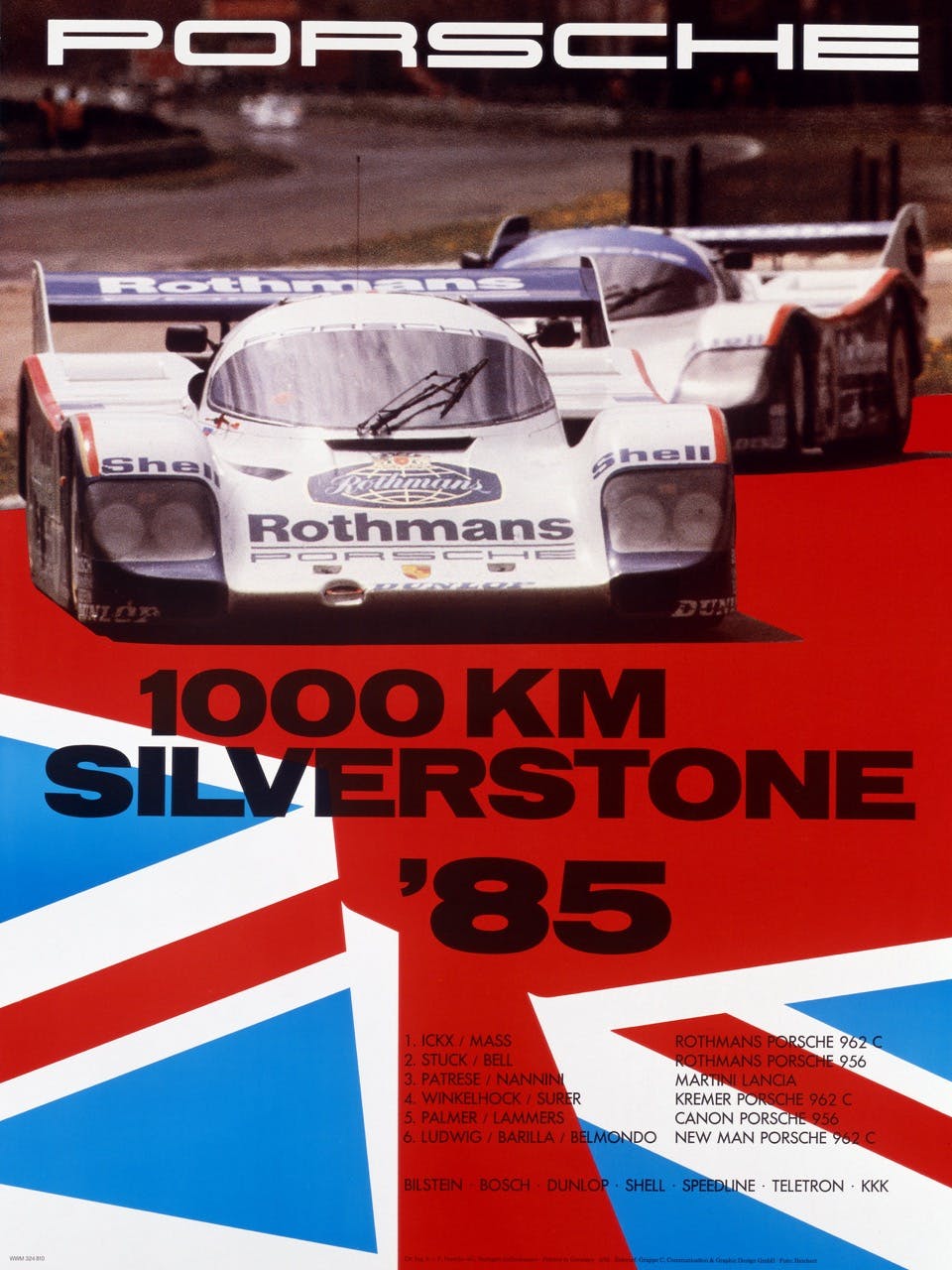

It’s now 40 years since Porsche’s 962 Group C race car made its competitive debut, with 77 examples of the all-conquering prototype raced worldwide by a who’s who of drivers. But one man drove more 962s more miles than anyone else: Hans-Joachim Stuck.

Stuck is also celebrating 40 years since he signed as a Porsche factory driver, yet he might never have driven for the German marque at all had he not “taken all my heart and called Professor [Helmuth] Bott at Porsche motorsport.” Because Porsche had, in fact, already ruled him out.

The 962 evolved from the 956, and Stuck’s Porsche connection began when he drove a customer 956 for Brun Motorsport at the 1984 Imola 1000km. He was paired with factory driver Stefan Bellof.

“In a 956 or a 962, you sit in it, you close the door, and you can 100 percent concentrate on driving with no worry about engine or gearbox failure or anything falling off,” Stuck says. “The combination of horsepower, tire width, and the immense downforce sucking the car to the ground made it unique to drive.”

Initially, the driving technique didn’t come easily to him, until Bellof demystified its nuances. “Stefan taught me how to brake into a corner, where to accelerate. It was completely new to me and I had to change my driving style entirely,” he recalls. “But if you forced yourself to go beyond what you thought was the limit and got in your brain what was possible, it was fantastic, with corner speeds you couldn’t normally achieve.”

Stuck and Bellof won Imola together, and when Bellof decided to wind back his sports car racing commitments for a complete F1 season with Tyrrell in 1984, Stuck spied an opportunity. He nervously picked up the phone to Porsche.

“When I called Professor Bott at the end of 1984, he said, ‘We thought about you already and assumed you had a lifetime contract with BMW’. Indeed, Stuck had spent much of the 1970s and early ’80s in BMW tin tops and BMW-powered formula cars, so it would be easy to make the assumption. “But then he immediately invited me to Stuttgart. Within half an hour I was a factory driver!” For 1985, Stuck would be racing the new 962.

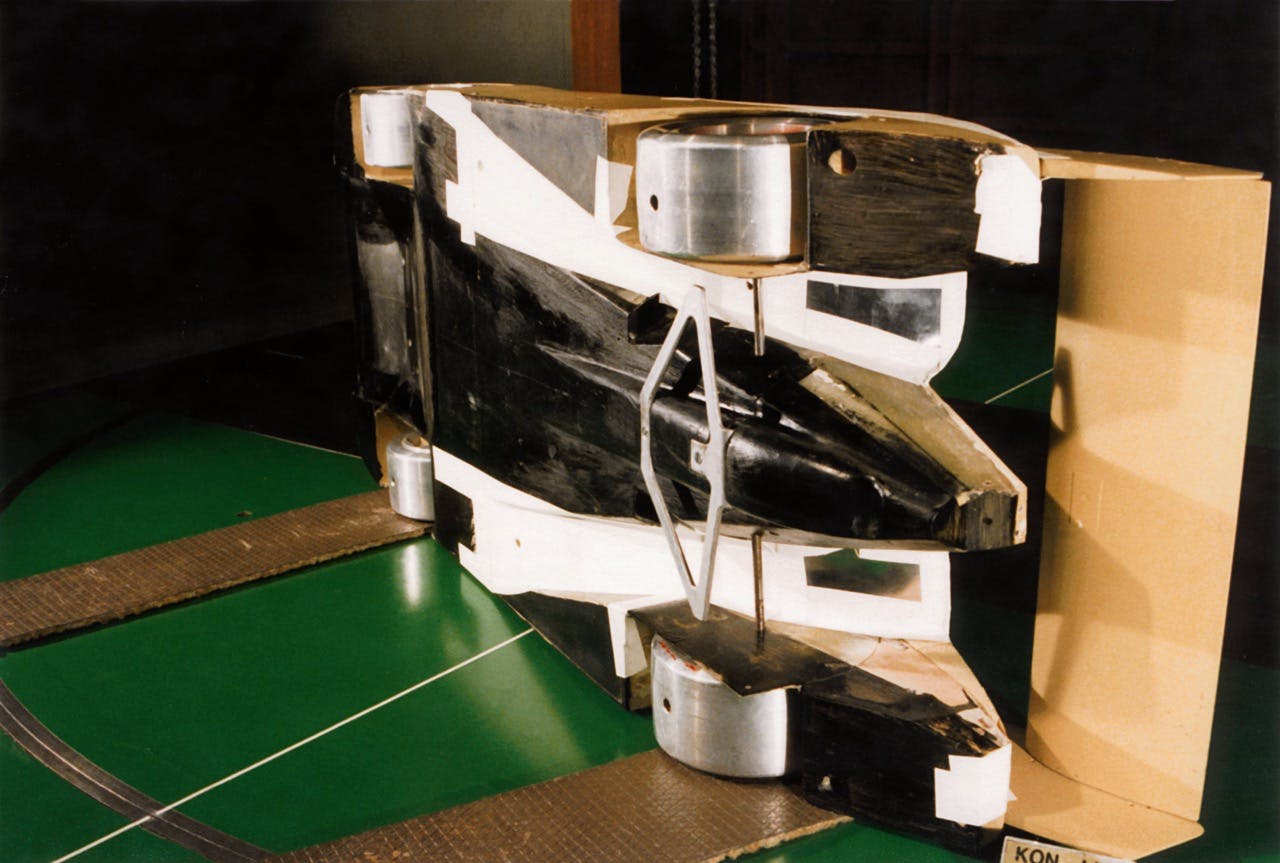

The 956 had debuted in 1982 with Porsche’s first aluminum monocoque and was campaigned extensively in European sports car events. But IMSA racing in the U.S. mandated a longer wheelbase that put the driver’s feet behind the front axle, rather than dangling ahead of it, and an engine based more closely on a road-going specification.

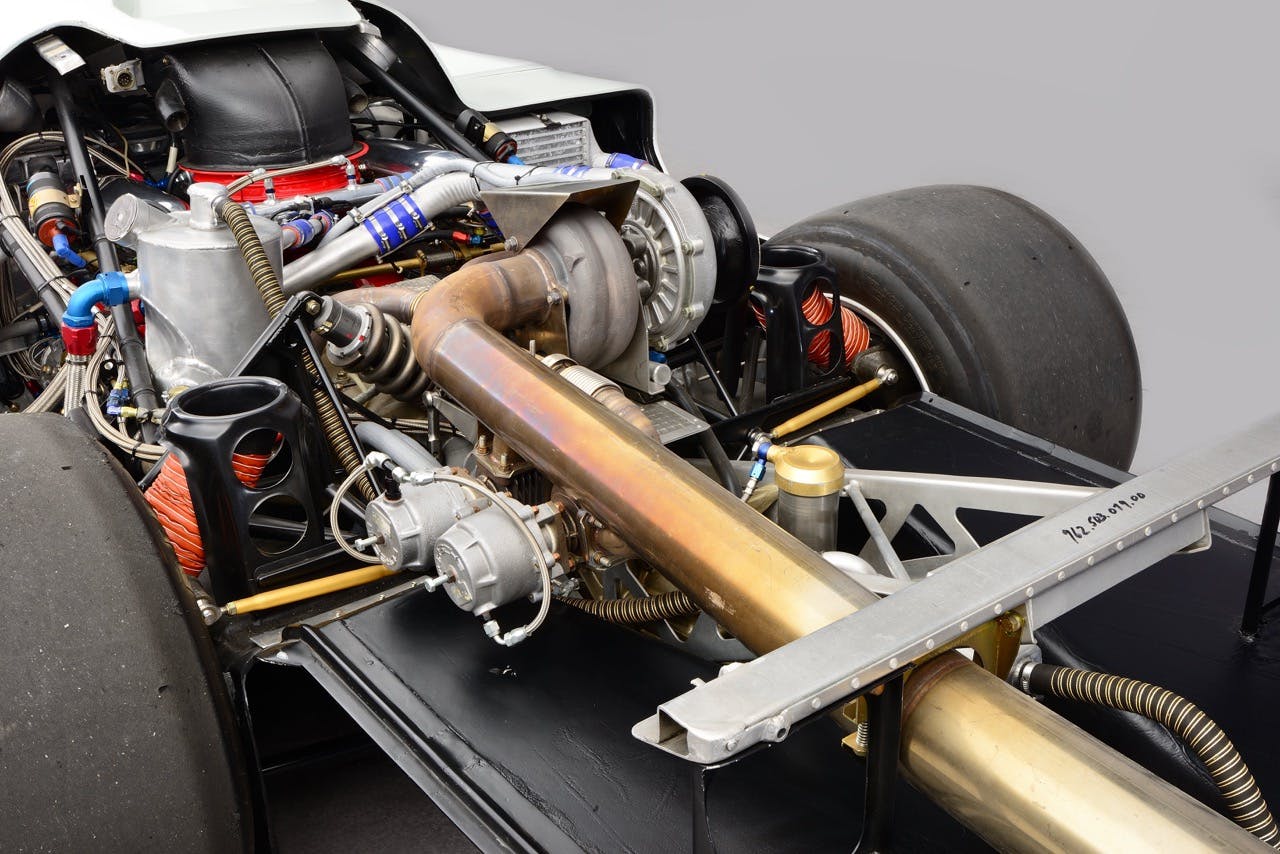

Hence the 962 has an extra 145 mm between the front and rear axles and a fully air-cooled, single-turbo engine, rather than the twin-turbocharged and water-cooled four-valve unit of the 956, which wouldn’t appear in the road-going 959 until 1986.

Based 125 miles away from Weissach in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Stuck was closest of all factory drivers to Porsche’s test track, and he was contracted for testing and development duties alongside his racing commitments.

So while he raced the 962 in IMSA, Interserie, and Supercup alongside the World Sportscar Championship, those development miles racked up his seat-time. After the fact, it was engineer Roland Kussmaul who confirmed it was Stuck who had driven 962s more than anyone else.

“I liked driving, I liked racing, and I liked testing, so I was really happy about it,” Stuck says with a smile. “I would even shake down every single customer car. The thousands of kilometers I did were an important part of my life. Other drivers might have two, three, or four weeks between every drive and then have to adapt, but for me it was daily business, and the more I drove, the more I learned. I was completely at one with the 962.”

A key part of Stuck’s work involved testing the PDK dual-clutch gearbox, after a new electro-hydraulic control system transformed it from the clunky and purely mechanical system previously tested on the 956. He liked it: “The first big advantage was keeping your hands on the wheel when you had all this downforce through fast corners. The second was no more mis-shifts, which could be very expensive, and the third was a lot of gain in time because you don’t have to go off throttle to change gear, so the boost stays up.”

Stuck thought there was room for improvement when it came to the 962’s handling, however. He complained to engineer Norbert Singer about the amount of understeer that the 962’s spool differential had on corner entry, which he believed slowed him down, even when balanced with its excellent traction on exit. Eventually, Singer agreed to a back-to-back test at the Nürburgring GP circuit to compare it with a mechanical locking differential. “Singer was right,” Stuck laughs.

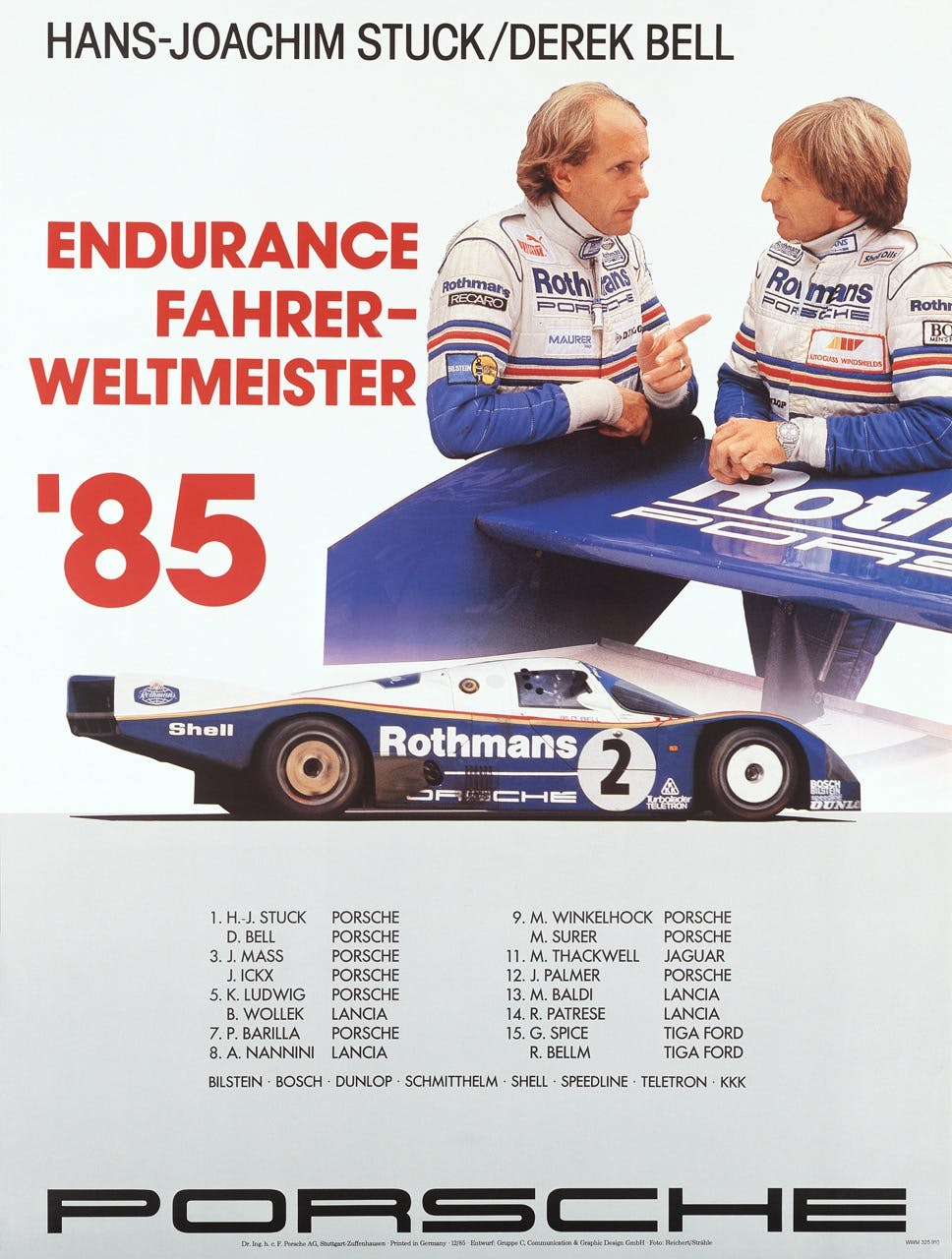

Stuck will be forever linked with British driver Derek Bell and American Al Holbert, with whom he won Le Mans twice. In fact, Stuck was key in assembling the dream team.

“When I was in the office signing my contract with Professor Bott, he asked who I wanted as my partner—Jacky [Ickx], Jochen [Mass] or Derek. Derek was already a good friend. He helped me in F2 during my first race at Hockenheim, when he overtook me and signaled me to follow so I could learn. It was a fantastic camaraderie.

“Derek was also taller than Jacky and Jochen, so there was no problem with the seat [Stuck stands 6′ 4″ tall]. Our partnership worked from first test. There was no ego that one wanted to be faster than the other, and when Derek was driving, I didn’t have to worry he would do something stupid.”

They won the 1985 World Sportscar Championship together, but a third driver was required for Le Mans.

“It was my idea to get Al Holbert because I knew him from years in IMSA with BMW and stuff like this. He was a leading guy on the 956 and 962 in the States, he fit perfectly with our team, and again, there was no ego,” says Stuck.

The three scored back-to-back Le Mans wins in 1986 and 1987. The first year was essentially a battle between various 956 and 962s, but Stuck emphasizes it was still a fight. Jo Gartner’s death in the early hours overshadowed the race, not least for Stuck, who’d won the Sebring 12 Hours with Gartner only a few months before.

“I was in the car when it happened,” Stuck recalls. “I didn’t know who crashed. We just had the long pace car. I asked [engineer] Peter Falk who crashed over the radio, he said he didn’t know, but when he called me in for a driver change an hour or so later, he took me into pits and said ‘I’m very sorry, your friend Jo Gartner got killed’.

“I couldn’t believe it and said I wouldn’t drive anymore. Peter said ‘Hans, you have a contract, you have to drive’. Getting back in the car and driving past the place Jo died was, let’s call it shit, you know? We were really good friends. After we’d won Sebring, I’d suggested to Peter that Jo should be a consideration for a works drive. He was a good guy.”

Later, standing with a winner’s garland on the podium, Stuck was full of mixed emotions. ‘When I started my career, I wanted to win Le Mans. It was one of the three biggest races in the world alongside the Indy 500 and Monaco, and I was there, in front of thousands of people. In that respect, it was definitely one of the best moments in my life. But good and bad are very close together in racing, you know?”

When asked if he is ultimately glad that he got back in the car, Stuck exhales for a long time: “Nobody asked me this before. . . . When I knew the funeral was coming up in Vienna, it was constantly in my mind. You know, Jo was one of two people driving that died during my career that really hit me. Ronnie [Peterson] was the other. He was at my parents’ place in Garmisch the Wednesday before, and then we drove together to Monza [where he was killed]. In the car I switched it off like a machine and it never influenced me, but off track I thought about it a lot.”

Stuck returned to Le Mans for 1987 with Bell and Holbert, and again won, partly thanks to Stuck’s heroic four stints.

“We were chasing Jaguar and it started raining during my first stint. In some places it was dry, sometimes wet, but I knew where, so I told Peter Falk, ‘Let me stay in the car, I know where I can make up time’,” Stuck says. “I did a second stint. Again there was a little rain, but I was fastest in the field, so Falk asked if I could do a third stint. ‘No problem!’ I caught the Jaguar and then did a fourth stint. It was 3 hours 55 minutes, the maximum driving time, and every muscle, every bone in my body hurt afterward. But during the race your adrenaline is so high you don’t even think about it.”

When the No. 17 Porsche 962 crossed the line, it did so with a 20-lap lead over the next quickest competition (another 962), signing off the most successful prototype era in Porsche history.

Stuck enjoyed a successful driving career well into the 2000s, but he never again achieved the same level of success as he had racing the 962 in Group C. He’s all too aware Porsche defined not just his career, but who he became.

“Before, I was maybe the funny guy, never taking care about anything. But with this move to Porsche, I learned to be respectful and it took me to another level professionally,” he reflects. “And driving the 962 as a factory driver was the utmost moment in my career. Porsche put together a car that was perfection for a driver.”

And none of it might have happened had Stuck not made that phone call 40 years ago.

Hans did much and was such a great precision driver. He set the table and then Bob Holbert took the 962 to the next level when they began building their own cars.

I can only wonder where this had all gone has we not lost Bob.

The greatest drive in Trans Am I saw was Hans in the AWD Audi. It was production based and he smoked the field at Mid Ohio. You have to hear Han Yodel.

He was the absolute best in the rain on a wet track. Incredible car control

Big fan. I remember during ESPN coverage of Lemans in 1987 during an interview he said “well the night is coming and we are going to drive balls out”. LOL.