Brabham BT44: Gordon Murray’s seductive Formula 1 beauty

First loves never completely lose their hold on us. So even though four decades have passed since Cosworth DFV-powered V-8s ruled Formula 1, I’m still captivated by the F1 cars of the 1970s, with their wide tires, wild wings, and wicked exhaust barks.

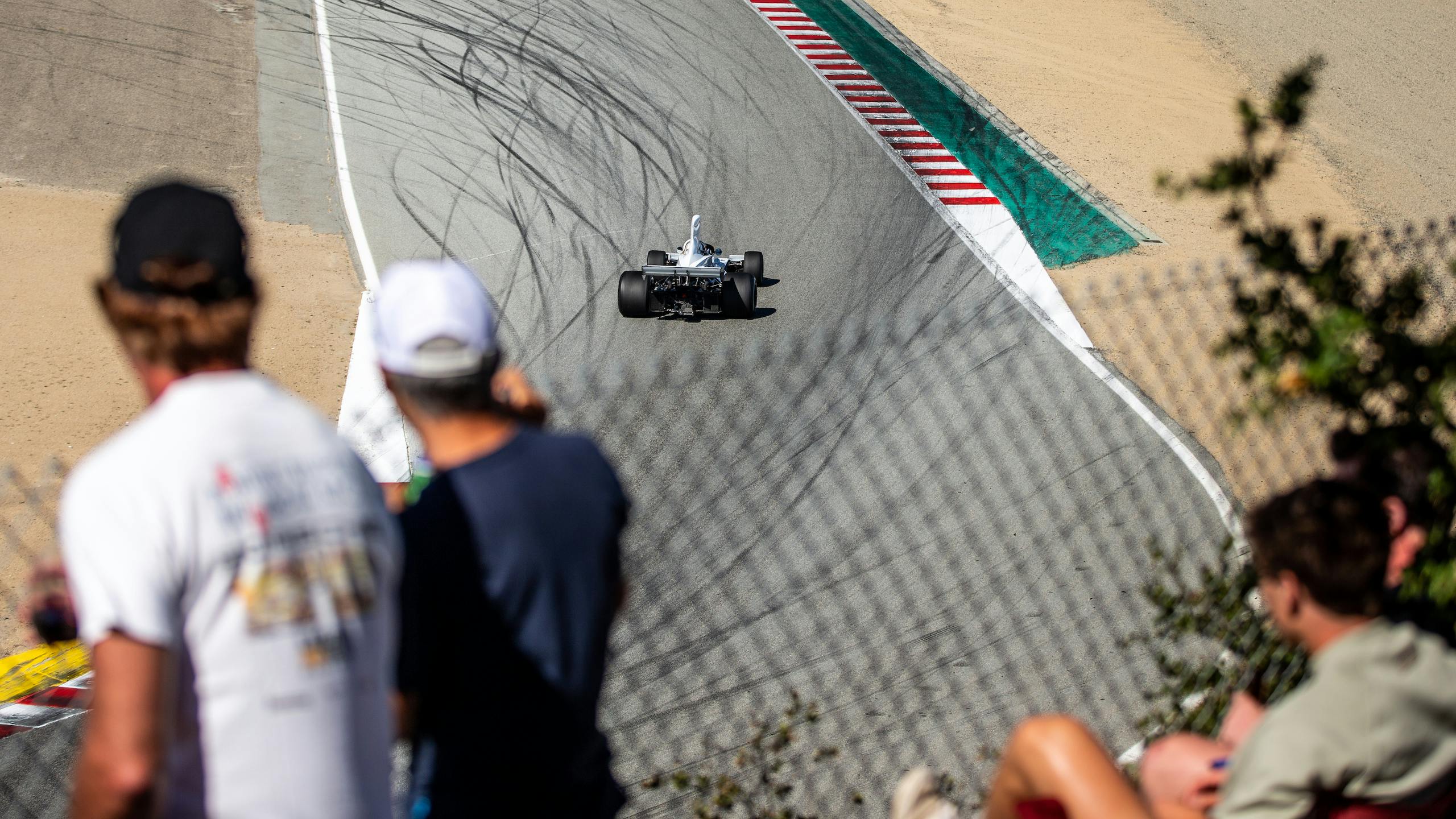

Initially, the cars that defined the era for me were the wedge-shaped Lotus 72 and the ground effects Lotus 79. These cars spawned so many clones that their shapes now seem almost passé, and after attending the vintage-car races at Laguna Seca more times than I can count, I’ve overdosed on the black-and-gold John Player Special livery. These days, the car that makes my heart flutter is a defiantly white trapezoidal projectile noteworthy for its unique shape, groundbreaking technology and sheer short-wheelbase bad-assery:

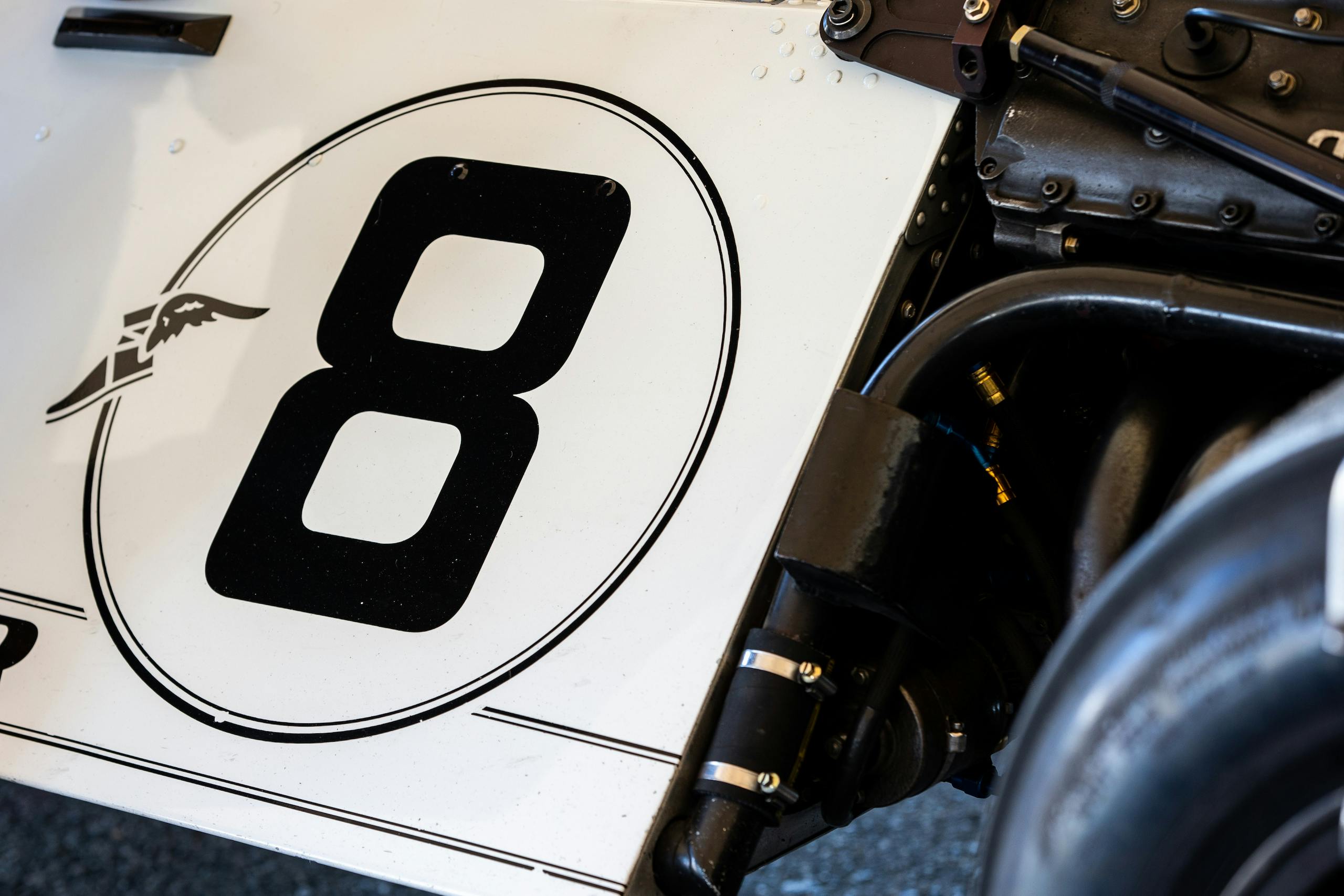

The Brabham BT44.

I’m not the only one’s who’s been seduced by the car’s charms. Phil Reilly has also been obsessed by the Brabham ever since he saw it at the 1974 U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen.

“I fell in love with the look, the concept of a physically smaller car, and all the clever touches,” says Reilly, who owns the BT44 that his friend and former Formula Atlantic champion Dan Marvin drove in the Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion last month. “The drivers [Carlos Reutemann and Carlos Pace] were charismatic, and [car designer] Gordon Murray was already a rock star. But owning one seemed like an impossible dream.”

Against all odds, Reilly—a Bay Area restoration maven best known for rehabilitating DFV F1 cars—found the Brabham advertised in Autosport back in 1985. When the ad kept reappearing, he finally contacted the owner. Reilly recalls: “At the end of the conversation, he said, ‘What do we have to do to get you in this car?’ like he was selling a Toyota!” Reilly ended up buying it—for himself, as a keeper—for about $15,000, paid over six monthly installments.

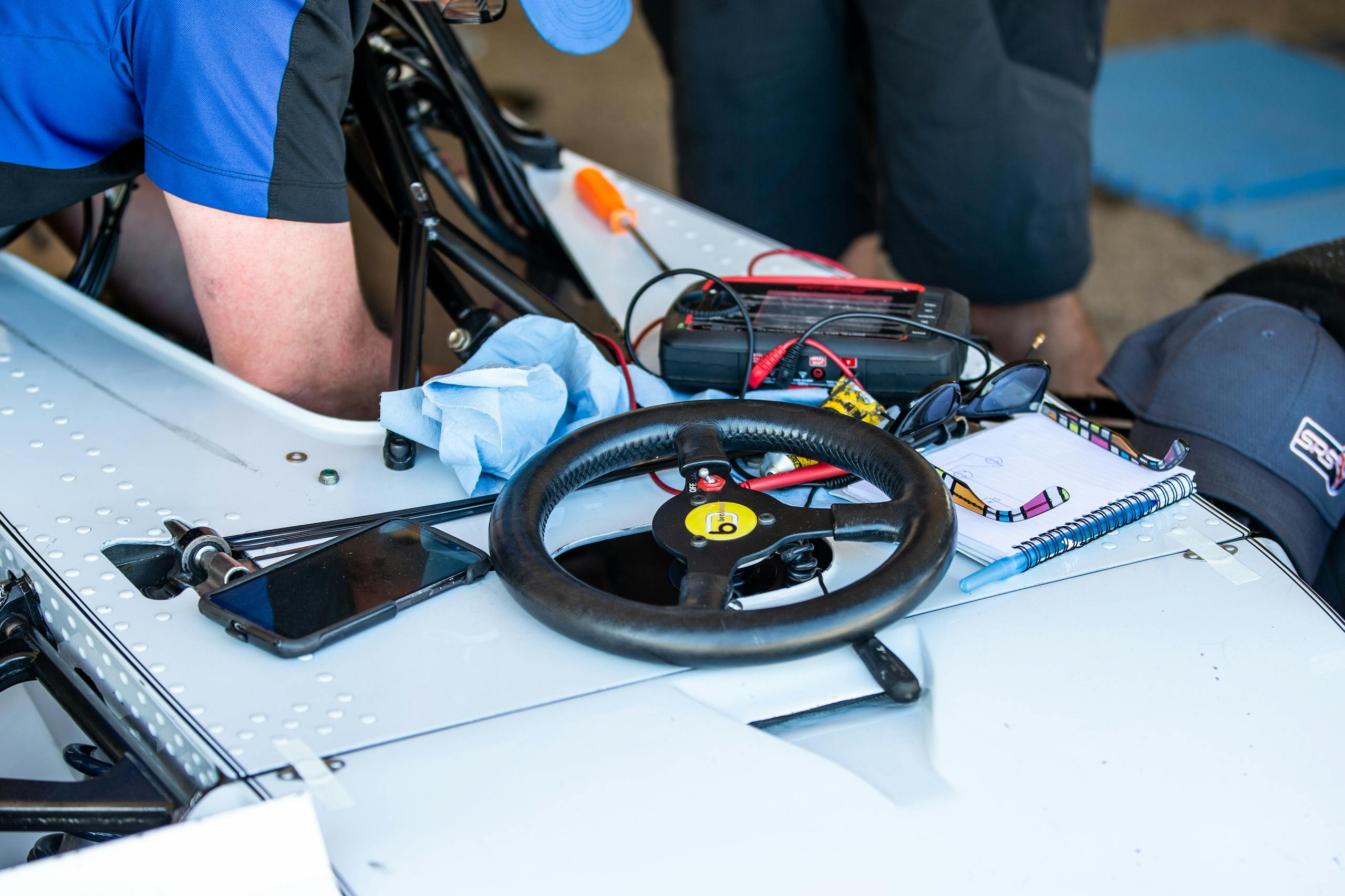

To his chagrin, he discovered that the Brabham wasn’t actually a BT44 but, instead, its predecessor, the BT42. But the differences between the two chassis were relatively minor except for the front suspension, which required heroic surgery. So Reilly used photographs and copies of Murray’s drawings to update the car. “There was a huge amount to fabricate,” he says. “And my wife, Kathy, bucked a lot of the rivets in the tub.”

Reilly’s Brabham is so faithful to the original that Murray called him after building his own re-creation of the BT44. “He said, ‘Would you mind sharing your setup with me?’” Reilly says with a chuckle. “I told him, ‘You understand the irony of this situation, don’t you?’”

Murray had joined Brabham shortly after moving from South Africa to England in 1969. Not long after the team was bought in 1971 by Bernie Ecclestone—yes, that Bernie Ecclestone—Murray was given carte blanche. The BT44 was the first of many seminal designs, and it remains one of his personal faves.

The car looked unique, with its triangular shape. It was also much shorter than its rivals, and the underside of the chassis hid a vestigial form of ground effects. But the most influential aspect of the BT44’s design was the front suspension. Murray used pull rods to achieve what was then known as a rising-rate suspension geometry. Although pull rods generally have been replaced by push rods to accommodate more efficient packaging, virtually every contemporary formula car can trace the lineage of its front suspension geometry back to the BT44.

The car was quick out of the box, leading in its debut in Argentina in 1974 before being sabotaged by a misfire near the end of the race. Unfortunately, this proved to be a sign of things to come, and the snake-bit BT44 recorded more DNFs than wins. But as it happened, the Grand Prix that Reilly attended at Watkins Glen ended with Reutemann and Pace finishing 1-2.

Reilly has worked on some of the most exotic and valuable race cars ever built, from pre-war Miller 91s and Alfa Romeo 8C 2900Bs to Ferrari 250 GTOs and enough F1 single-seaters to fill a grid. His personal collection includes the Kurtis/Epperly laydown roadster that A.J. Foyt raced at Indianapolis in 1960.

The BT44, though, is the car that’s never getting away.

“People have waved some pretty big checks under my nose, but I’m going to die with that car,” he says. “If you want to buy it, you can talk to my widow after I’m gone.”