The Triumph X-75 Hurricane’s speed will blow you away

Triumph builds some very attractive motorbikes these days, including stylish Scramblers, the pared-back Bonneville Bobber and mighty Rocket 3. But it’s debatable whether any recent model matches the visual impact that the old Triumph firm made half a century ago, with the X-75 Hurricane.

Not that the Hurricane’s elegant, wasp-waisted looks were the only thing for which the 740cc triple was memorable. Its 60bhp engine, a lower-geared version of the unit that powered the T150 Trident and BSA Rocket 3, made the Triumph one of the world’s quickest-accelerating bikes when it hit the road in 1973.

Given the Hurricane’s style, performance and rarity—fewer than 1200 were built, all between June 1972 and January ’73—it’s no surprise that it is among the most admired of Seventies classics. It has one of the most unusual back-stories, too, because it was designed without the bosses at Triumph’s former factory at Meriden, near Coventry, even knowing about it.

The X-75 was shaped not in Britain but in the United States—in top secret, by a young freelance designer named Craig Vetter. In fact the whole concept originated in the U.S. with Don Brown, the vice-chairman of BSA’s American company.

When the original Trident and Rocket 3 triples had been revealed in late 1968, American market reaction had been very poor, mainly because of the bikes’ unusual, angular styling. “The only way we were going to sell the triples was by restyling them,” Brown later recalled. “And I knew that because BSA Group executives approved the original Rocket 3’s styling, I’d have to get the bike restyled on my own, in the U.S.—and in secret!”

Brown approached Vetter, who had started a business in Illinois making fairings, and had just displayed two stylish bikes of his own design at a show in Daytona, Florida. Vetter flew to BSA’s base in New Jersey with some initial sketches that impressed Brown. “He was a long-haired, hippie-type guy—a free spirit—but he was a keen thinker and ambitious,” the BSA man later recalled.

It was agreed that the project would be kept secret even from the BSA Group’s chairman and managing director, and Vetter was provided with a standard Rocket 3 on which to start work. His prototype retained the BSA’s angled-forward, pushrod-operated engine and twin-downtube steel frame.

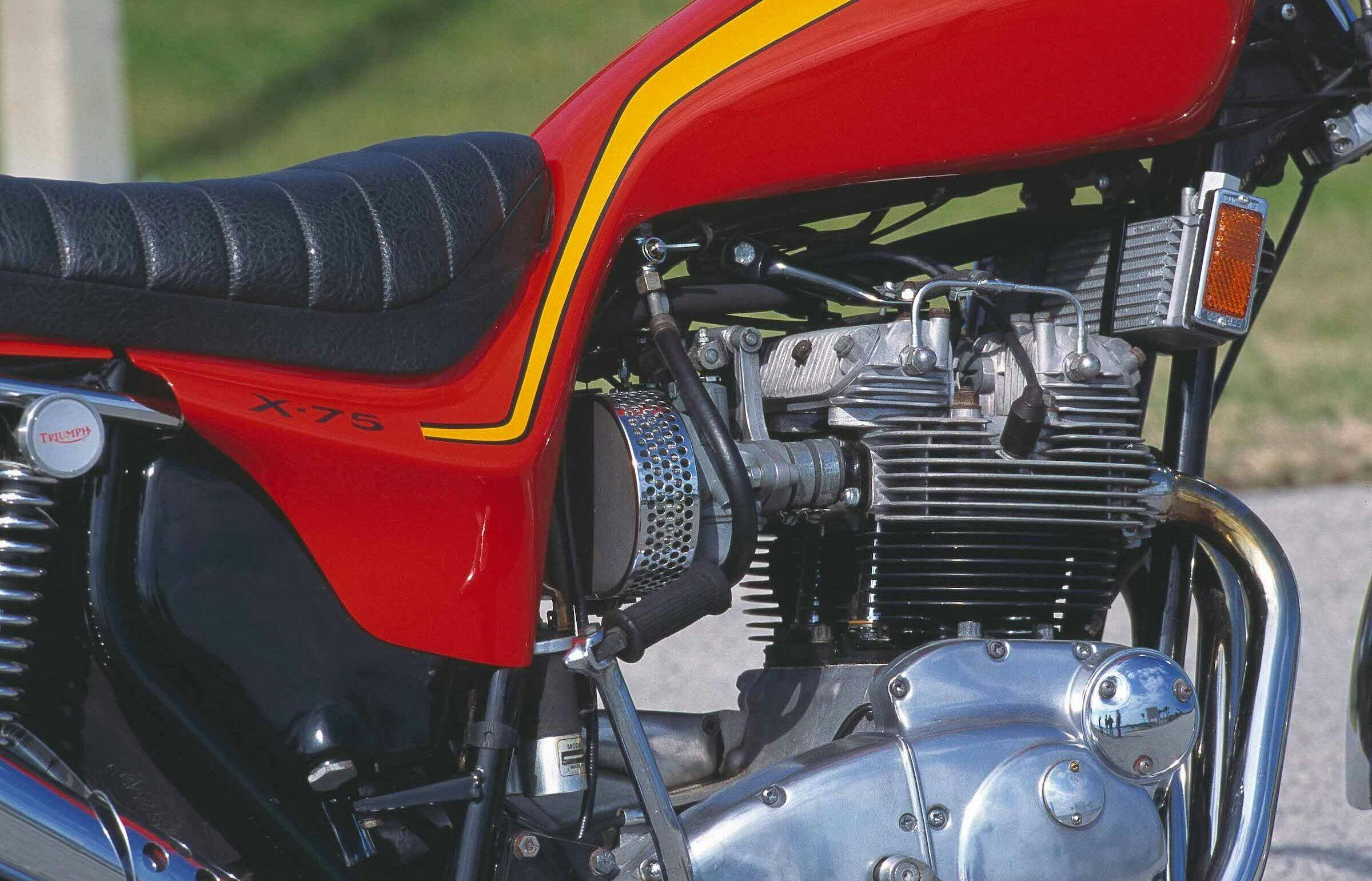

Vetter extended the cylinder head’s fins to make the motor look bigger and more impressive. The handlebars were higher, clocks were mounted above a new chromed headlight, and front forks were lengthened by 50 mm. Three exhaust downpipes slanted across the front of the motor, then ran back to the bank of shiny, upswept silencers on the right side.

Most importantly, the original slab-sided bodywork was replaced by a slender fiberglass form that blended the fuel tank into the sidepanel area, above which was a dual-seat with a chromed pillion grab-rail. The arrangement was inevitably impractical—the tank held only 10 liters—but the visual effect was striking.

Despite the secrecy surrounding the project, the American BSA firm’s president Peter Thornton heard about the prototype, and asked Vetter to bring it to New Jersey. When he arrived, the reaction was so positive that Thornton had the bike shipped to Meriden the same day – complete with instructions that it was to be built with no changes.

Even so, the Hurricane’s progress to the production line was far from smooth. Brown and Vetter had envisaged the triple as a BSA, and the first pre-production bike assembled at Triumph’s Meriden plant wore the rival marque’s badges. But BSA’s financial collapse ensured that the model was eventually marketed as the Triumph X-75 Hurricane.

Incorporating remarkably few changes from Vetter’s original prototype, the Hurricane turned plenty of heads when it was launched. It still looks stunning, at least from the right. The view from the rider’s seat is captivating, too; dominated by the narrow petrol tank, chromed headlight and a round friction steering damper.

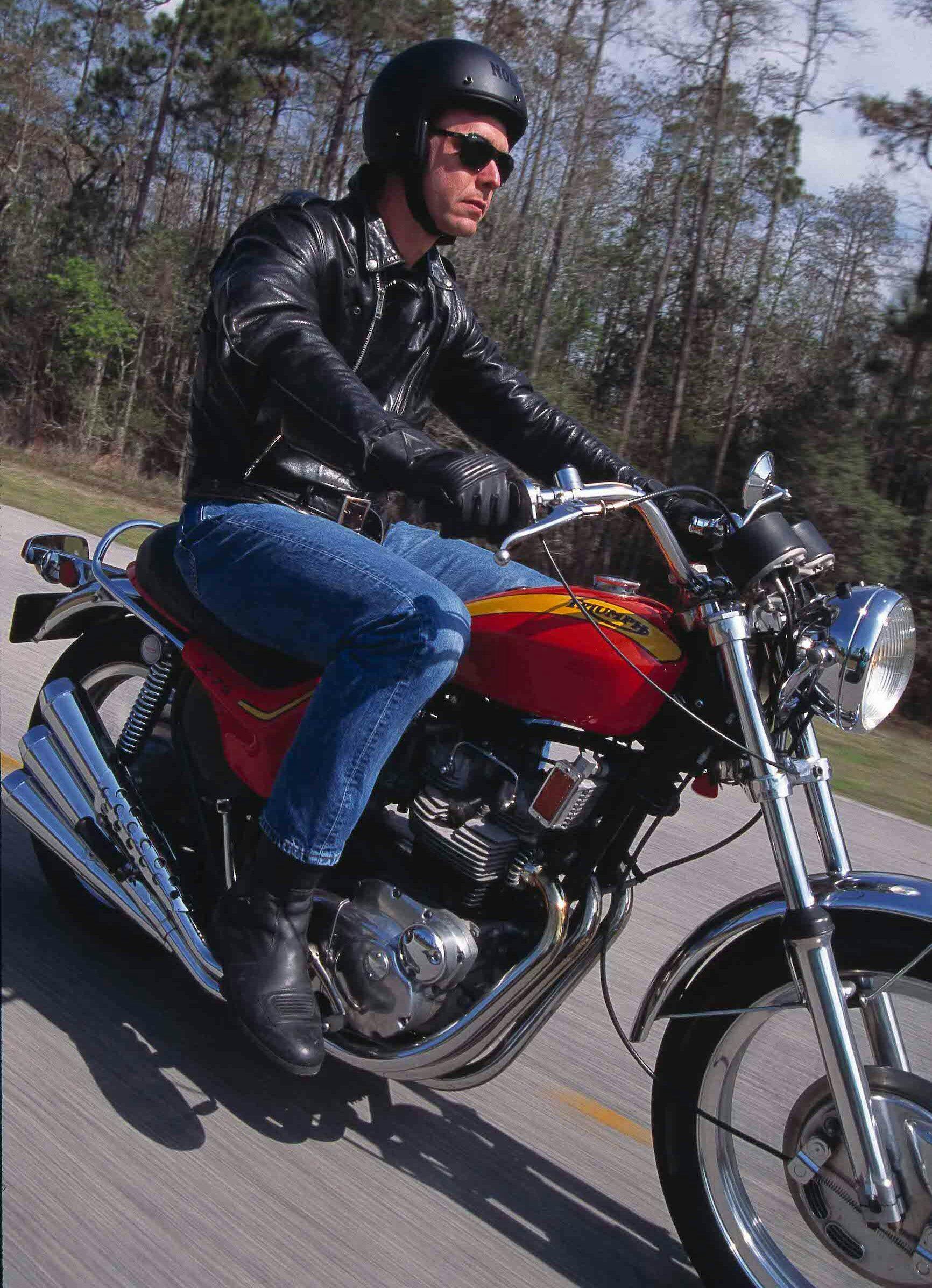

The handlebars are more wide than high, giving a bolt-upright riding position with feet well forward. Ignition is on the left, below the steering head; the choke lever sits on the bank of Amal carburetors. There’s no electric start but, given a gentle prod of the kickstart, the Triumph burst into life with a pleasant three-cylinder warbling.

With its flashy looks, potent engine, feeble fuel range (realistically as little as 60 miles, given the triple’s 30 mpg thirst) and short gearing, the Hurricane was aimed unashamedly at urban cruisers and traffic-light racers. Although fairly tall, at 191 kg it was respectably light, too—a useful 20kg lighter than the Trident.

That helped make the Triumph feel refreshingly quick as I set off. The three-pot engine traditionally likes to be revved, but the Hurricane pulled fairly well from low revs, kicking harder above 4000 rpm and emitting a wonderful exhaust wail as the revs rose towards the peak power figure at 7250 rpm.

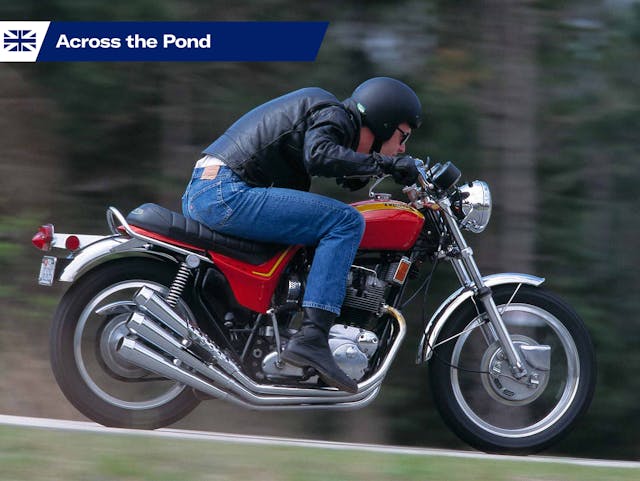

The impression of acceleration in the lower gears was terrific by Seventies standards, enhanced by the exposed riding position and short gearing. I had plenty of opportunity to practice my right-foot change on the five-speed Hurricane, whose top speed of about 115 mph was 10mph down on the T150 Trident’s—although it was half a second quicker over the standing quarter-mile.

The Hurricane earned a dubious reputation for handling thanks to its combination of high bars, kicked-out forks and ribbed front tyre. This bike was stable in a straight line, and delivered a fairly sporty ride thanks to firm shocks and front forks that, although long, were reasonably well-damped. Its twin-leading-shoe drum front brake gave a soft feel at the lever but worked reasonably well, aided by the smaller rear drum.

Ultimately the X-75 was less about performance than style and attitude. The Trident was a better all-round motorbike—faster, more stable, better braked, more comfortable at speed and with better fuel range. But the Hurricane had the looks and acceleration that made it more popular with many U.S. riders.

Unfortunately, by the time it was released the BSA Group (of which Triumph was a part) was in a financial crisis. This affected Craig Vetter, who was not paid for his work for many months. Even then, he only got his cheque for $12,000 after a personal appeal from Don Brown, who had left the company.

Vetter went on to become famous in the bike world for his firm’s aftermarket fairings and luggage systems. But as long as the Triumph X-75 Hurricane is ridden and admired, its designer will be remembered as the man who brought a touch of Stateside glitz to the classic British triple.

***

1973 Triumph X-75 Hurricane

Highs: Looking at it from across the parking lot

Lows: Too-frequent fill-ups

Summary: Seventies cool … with a kick

—

Price: Project: $12,000 Daily rider: $19,800 Showing off: $28,500

Engine: Aircooled transverse triple

Capacity: 740cc

Maximum power: 60bhp @ 7250 rpm

Weight: 191 kg without fluids

Top speed: 115 mph