Then and now, the Triumph Bonneville just has it

Let me take you back in time, 70 years or so, to the smoke-blackened brick arches on London’s North Circular. Look carefully and you’ll see a glint of chrome, a flash of silver helmet and nasty-man goggles, fisherman’s wool socks folded over the tops of tall black boots, creaking leather jackets, and then the crack of a parallel twin responding to a kick start …

Back then, there was only one arterial route ’round The Big Smoke. On the west side of it, just up from the Hanger Lane and feeding and watering the inner soul of haulers and bikers, was the Ace Café, a greasy-spoon mecca that sounded like a cross between an idling Scammell, a wheezing Gaggia coffee machine, Bill Haley and the Comets on the jukebox, and a fair slice of braggadocio. When time hung heavy, the young blades would tear-arse their machines up the road, to a roundabout, and back, with pride going to the fastest.

Attending the 60th anniversary a few years ago, I encountered Brian Winch, who was an Ace regular in the early 1960s, its biking heyday. At 19 years old, he rode a nearly new 1961 Triumph Bonneville, bought for £189 (roughly $4500 today) at Pankhursts in Salisbury.

“It was like a space rocket in its day,’ he told me. “On Saturday evenings we would ride up from Southampton through Camberley, to the Ace. Sometimes we’d go on to the Busy Bee Café on the M1, or we’d stay here and sleep in allotment sheds or in the railway carriages in the shunting yards. It was a basic transport café then; the food was edible if you were hungry. It wasn’t a great place to pick up women, but most of the lads bought their girlfriends if they had them. We used to all ride together—the bikes were smart, with lots of chromium plate. We didn’t call ourselves ‘rockers’, just ‘bikers’ and we didn’t go to pubs, just cafés.”

Bonneville was king of the hill in those days—cheap, fast, flash, and with reasonable handling once Doug Hele, who was bought in from Norton, had sorted it out. A Norton with a “Featherbed” frame handled better and was more comfortable, a BSA had a better engine, but the Triumph just had it! Marlon Brando, Bob Dylan, Clint Eastwood, and Steve McQueen certainly thought so, and in truth this was an American machine, demanded by those West Coast bikers who wanted a bit more urge from their Triumphs than what they’d been given before.

And what they got was a 120-mph, stone-cold classic. “Arguably the best British bike ever made, and is certainly one of the few that is both reliable and competent in modern traffic,” wrote Frank Melling of the 1968 model in The Daily Telegraph. “One of motorcycling’s most enduring Great British icons,” said Steve Wilson in Triumph T120/T140 Bonneville. “Big grin,” says Henry Cole on YouTube. “In modern traffic conditions, for me, it’s perfect.”

From working man’s road rocket through two generations to pure nostalgia in its third generation, but with a satisfying hint of the rebel and a surprising degree of practicality. Perhaps that’s why the name still exists today on the side of the modern 21st-century John Bloor–owned Triumph parallel twin, which was launched in 2001 and is still a mainstay of the Triumph marque.

Turn the clock back again, though, and think about the redoubtable Edward Turner. Born in Southwark in 1901 into a family of engineers, by 1929 he was married and working at Ariel where he designed the famous Square Four engine. When Ariel went bust in 1932, it was bought by industrialist Jack Sangster. In 1936, when Sangster purchased the newly independent Triumph motorcycles, he moved Turner across as general manager and chief designer of what was then called the Triumph Engineering Company. Turner rationalized the Triumph range and set to at the drawing board. In 1937, the result was the epochal 500cc Speed Twin. Smaller and lighter than the rest of the Triumph range, it retailed at £75 (roughly $5270 today) and its 29-hp twin could propel the 366-pound machine up to 90 mph. That fantastic piece of design set out the order of battle for British motorcycles until the ’80s.

Turner was a prodigious talent, a genius even, but as colleague Burt Hopwood put it, he was also “hopelessly egotistical.” He argued with Sangster and left for BSA, leaving Hopwood in charge, but after World War II, Turner returned to Triumph and set about developing a model range where the genesis of the Bonneville was introduced. TRW, Tiger Cub, Terrier, T110 Tiger, and the unit construction 3TA all contributed to the Bonneville, which was Turner’s last design for Triumph, though he was said to be concerned about the performance; actually, for the early models, it more than the frames and suspension could cope with.

“This, my boy, will lead us straight into Carey Street,” he said, an idiom for bankruptcy.

The Bonneville name came from the small town near the eponymous salt flats, where in 1955, plucky American speed record breaker Johnny Allen rode his Triumph streamliner, Devil’s Arrow, at a new record pace of 193.3 mph. Bonneville was launched at the 1958 Earls Court Motorcycle Show, although with their usual ability to miss the big stories, the film news coverage from the show completely failed to mention the new iconic Triumph.

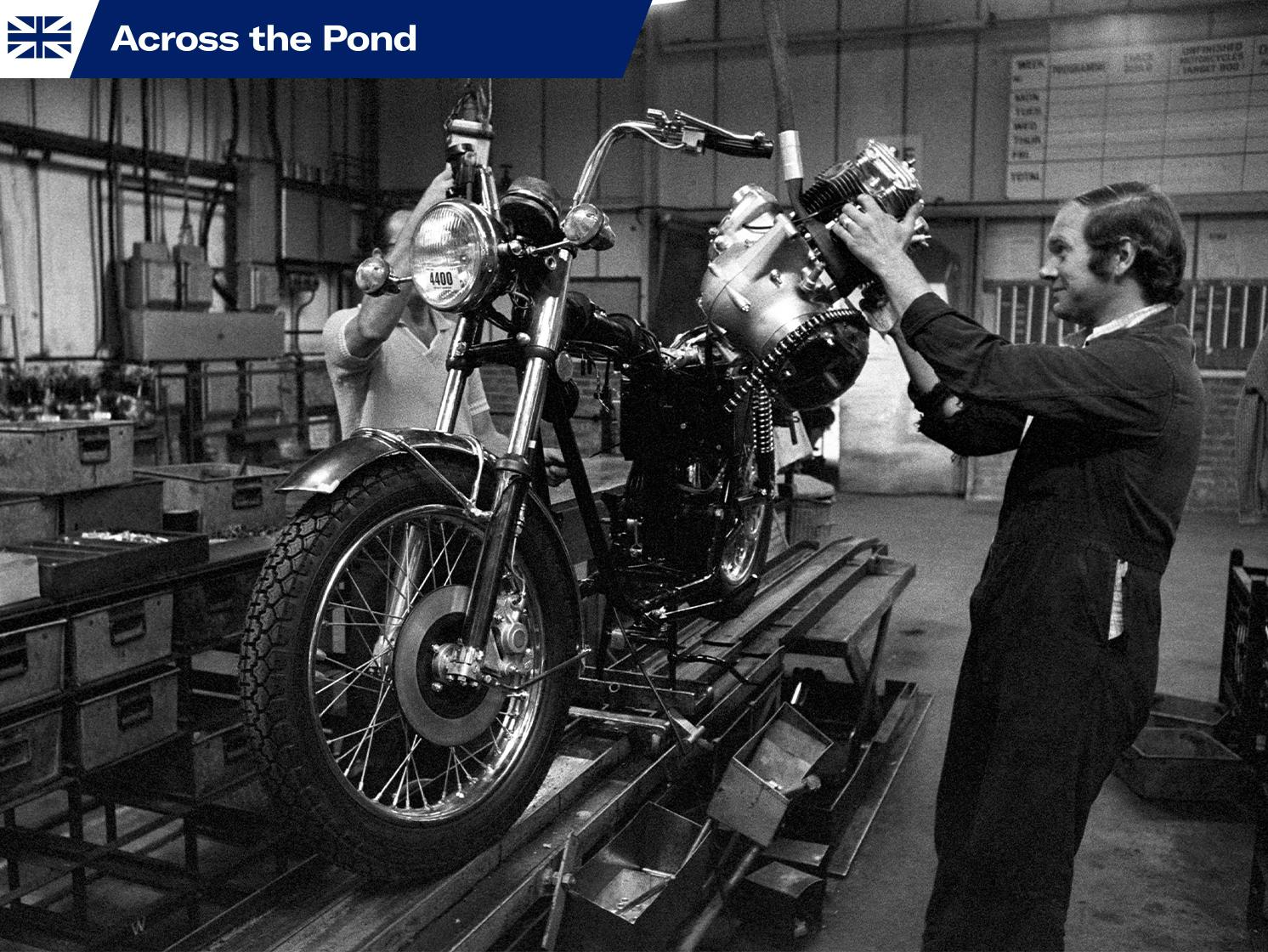

In fact, the launch seemed to pass many of the media by; after all, the bike was a hopped-up T110 Tiger. Even in America, the new Triumph was scarcely noted at first, but that didn’t last. Before long, Triumph was struggling to fulfill home market orders as supplies of the 650cc twin headed across the Atlantic to Canada and America. But even by the mid-to-late ’60s, and despite the 1963 inclusion of Triumph’s unit-construction engine and various fork and frame improvements, the writing was on the wall, especially with the 1969 launch of Honda’s CB750. The end came in the ’80s amid the collapsing chaos of the once all-dominant British motorcycle industry.

So, what are those early machines like to ride these days? Still brilliant, to be honest. There’s a fair bit of faffing around before the start with all that turning on of fuel taps, tickling of concentric carburetors, and so on. For those born to electric starts, there’s a knack to the kick start, but it is soon learned: Kick it like you mean it and the twin bursts into burbling life, which has to be delicately maintained on the throttle until warm-up is achieved. The right-hand gear change should pose no problems and it really does feel fast, gaining speed quickly and (if a later model) feeling quick to turn into corners but not unstable.

Fast corners will have the frame wombling around a bit, but it’s stable. Just don’t rely on the brakes too much, especially the single leading-shoe originals. As for the performance, well, across Beaulieu Plain in my youth, a well-maintained Bonneville could just about keep up with a Yamaha RD250 and, as my mate Al always said: “The sound you are hearing is all the engine bits trying to get out.” But my goodness, it was a sound and a half.

The T120 stayed in production until 1973, but in 1971, amid the growing chaos of Norton Villiers Triumph’s finances, the oil-in-frame T140 was introduced. These later machines were scorned by purists, but something strange has happened in the last decade or two as old men gathered up huge collections of British machinery, which kept prices high and the legend alive. But these machines weren’t exercised and the whole thing became a sort of pyramid scheme. Prices rose high even for fakes, imports, and bitsa machines, and so the younger lads and lasses went for the T140s and gave them their love. The irony is that now the old collectors are getting too old even to wobble ’round their miserly hordes; the bikes are being sold off and, as a result, prices are easing a bit.

To own an old Bonnie is a cinch. The bike requires just one annual service and resists the siphoning of its oil onto the garage floor a bit better than its Norton rivals. With modern ignition systems and specialists, parts are available and reliability is good. Plus, there’s a lot less snobbery about which machine you’re on these days.

You’ll smell of hydrocarbons and oil, and you’ll spend time at the side of the road, but somehow, the world looks more full of opportunity and fun from the seat of a Triumph Bonneville …

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Had a ’63 in about ’72-’74. Sweet ride, but she was worn pretty thin by the time I got her. Always wished I’d kept her and done a proper restoration, but really didn’t know what I had ’til it was gone!

Loved British motorcycles; learned to ride on right hand shift bikes in 1966. Owned a ’62 BSA Super Rocket & a ’68 BSA Firebird Scrambler. Nothing like the sound of a 650cc British bike with megaphones.

Had 67’68’ and a basket case 1969.

Liked the 1968 Bonnie Best.. to buy new again it would have been the TR 6 with single carb..less fuss.

It’s a great looking bike.

I believe the later Bonneville’s had a dual-leading shoe brake. They were beautiful motorcycles then, and still are today.

The 1968 BSA Spitfire MK IV had the twin leading shoe front brake with the fair vent.

When the BSA / Triumph deal came about some Triumph models got that front hub.

All Triumph’s and BSAs, including the triples, received the new Tls front brake in 1968. The first ones had the cable coming in on the bottom, for 69 and 70 the cable came in from the top. Still one of the best Tls brake ever made!

BSA bought Triumph and destroyed it; many believe deliberately. The common oil-in-frame design required that the Triumph engine be partially disassembled to install it. The electric start that Triumph planned to install wasn’t developed (the button is still there) but doesn’t do anything. The seat was/is 31″ above the pavement, which basically means that the owner must be over 6′ tall to be able to ride it or even start it. I’m 5’8″.

I’ve insured mine with Hagerty for at least two years and never left my driveway. I still have hopes. I recently bought a shorter center stand, which at least allows me to get it up without putting a piece of plywood under the rear wheel.

If BSA bought Triumph to deliberately destroy it then that plan didn’t work well for them.

Triumph emerged the survivor and BSA was discontinued.

Having been employed at a BDA / Triumph dealership at thectimecall that was going on I’m fairly certain that he Japanese bikes market share had started the decline of the British bike industry.

In order to hang on a little longer BSA / Triumph knew they could only market one brand.

A simple check of the previous years sales worldwide showed Triumph to be the top dog.

The rest is, as they say, history.

In my time I have owned a 55 TRW, and 3 Norton’s, two being 750’s and a 850. I know the sound of a British twin coming long before it is in view. 🙂

I know this is a Triumph article but I e a story that sort of has a few Triumphs in it.

I bought a new leftover 1968 BSA Spitfire MK IV in 1969 and shortly after went to work at the local BSA dealership, who also sold BMW, Suzuki, Greece’s, Penton and then later when the Triumph/BSA deal he also sold Triumphs.

The shop owner and his brother were both half milers and knew how to tune.

I put megaphones on the Spitfire, rejected the carbs after switching to velocity stacks and dropped the counter sprocket one tooth.

I still have a time slip from National Trails dragstrip in Ohio from 1970 with a 14.12 ET & 95.54 mph.

In the small town I lived in there were two die hard Triumph riders who thought they ruled the town but neither one would run mevfrom a dead stop.

One finally got his nerve up to do a first gear roll on.

The only thing he saw was the rapidly shrinking BSA logo on the back of my seat.

He wanted to try a second gear roll on and fared even worse.

He told his Triumph buddy that it wasn’t a good idea to run me, in any fashion.

One of their buddies had a new 750 Honda (that he didn’t know how to ride) and he thought to teach me the superiority of his CB750.

He mad the mistake of agreeing to run me from a dead stop and I smoked him twice in a row.

On the third run I had a bad launch and he managed to just sqqueei by me at the end of the quarter.

I tried to get another run out of him but he was satisfied with beating me 1 out of 3.

When the BSA / Triumph deal went through my boss started selling Triumph asceell so I had the opportunity to work on both.

Aesthetics are subjective so whether the BSA or Triumph was the best looking can be debated endlessly.

Mechanically the Triumph had a duplex primary while the BSA had a triplex.

The Triumph frame was bolted together.

They were just not as robust as the BSA.

As most readers of this article are aware I’m sure it was the market share that gave Triumph the win when it came down to dropping one of the bikes.

A simple case of which one sold the most units in the previous year was the deciding factor.

Some years later when I had my own shop I took a very low mileage 5 speed, oil in the frame Bonneville in on a trade and rode it for quite awhile.

It was a very well made bike and very reliable but it just did have the charisma of my BSA Spitfire MK IV.

I’m glad to see and hear that the older Brit bikes are still popular, regardless of the brand.

Oh, a very good article, thanks for publishing it.

Jimmy, I bought a ’68 Firebird with 700 mi on it in ’71 – still have it, still ride it. It pulls ‘gee wizz kids’ away from just about everything else when stopped. On a trip back from FLA to Ohio I discovered the factory had sabataged the otherwise fine engine when I found the connecting rod that didn’t fail had nuts that were barely tighter than finger tight. Have you found this before?

My 2006 Bonneville is the best bike I’ve ever owned and I have owned just about every Japanese and American produced.

100% agree with the Hinckley Triumphs. I brought the first ones into China back around 2009. Sold them right off, and then when I moved back to the US i bought another, a 2010 fuel injected Bonneville. Put a sidecar on it and put 30,000 miles on it in one year. Did an Iron Butt run from Dallas to Vegas in 23 hours. Then rode it Vegas to Sturgis via Reno, and back. Rode it from Vegas to Daytona and back. All that time the only think I had to do to it was replace the fork seals. I finallly sold it and am looking for my next one.

I learnt to ride on my older brothers 58 Thunderbird 650 at 14, I bought a 5TA Speedtwin 500 at 15 and when I was 18 I bought a 71 650 Bonnevile with a twin leading front brake and air scoop. All were preloved,but my 4 speed Bonnie could beat my friends 71 Norton Commando through the tight and twisty hills. I had it for about 10 years before it was stolen

Okay, their I was 1964 sophomore in High School. Dad was charter member of AMA, four sisters and a brother. All only had Harleys. I bought a twin 600cc Norton on 58 feather light frame from a Bultoco dealer that was a flat tracker. It didn’t matter what I ran against, my Norton would take them, 900 sportster’s, Honda’s. No matter. I also has a 650 Triumph, not a chance of caching my Norton.

It seems odd that the outside pushrod tubes are not mentioned. They were pretty. They leaked. We used to double up the seals top and bottom, and argue over which color-code of hermetite to coat them. Didn’t work.

And now I wonder whether “hermetite” is the hot keyword that sent my comment to moderation.

1965. Walking to Alameda Navy base from off base housing, a bonnie turned the corner a 1\2 block from me. Dual megaphone exhaust pipes, sweetest sound I’d ever heard. Had to have one. Best I could do was a 500cc AJS. E4 pay. Would do that over in my dreams from then on.

I had a 1976 Triumph Bonneville. I had the gas tank painted with a Union Jack. See Led Zeppelin’s drummer John Bonham’s bike in the movie The Song Remains The Same. That’s where I got the idea. Still don’t understand how they could build a motorbike in England that wouldn’t start in the rain! Thank Lucas Electronics. Also my right calf is still bigger than my left from having to kick start it over the years. I still have the scar from when it kicked back. It handled like a dream and was best looking bike broken down on the side of the road.