The Yamaha RD350 Was the Best Bike of the ’70s

Ask a motorcycle enthusiast who lived through the 1970s to name the best bike of that memorable two-wheeled decade, and they’re likely to mention a multi-cylinder Honda or Kawasaki, or perhaps a glamorous Italian V-twin or triple. Inquire about the best one they’ve ridden, and the answer is far more likely to be Yamaha’s RD350.

Half a century ago, Yamaha’s two-stroke parallel twin was the ultimate superbike for the young rider—quick, exciting, and relatively inexpensive. The Japanese firm produced a string of excellent two-stroke twins of various capacities during that fast-changing decade, but it was arguably the RD350, launched in 1973, that really hit the mark.

Those RD initials stood for Race Developed, and they helped differentiate the new twin from its similarly styled predecessor, the YR5. In the RD350’s case the slogan was justified. Yamaha’s TZ two-stroke twins had dominated club- and national-level 250cc and 350cc racing worldwide for several years, to the benefit of its street bikes.

Yamaha had won the last three 250cc world championships, too, through British riders Rod Gould and Phil Read, and Finnish star Jarno Saarinen. And although Giacomo Agostini still held the 350cc title on a works MV Agusta, the TZ350’s many victories included Don Emde’s Daytona 200 triumph in 1972, and Saarinen’s win on the same Florida banks a year later.

Yamaha’s road-going twins, which were air-cooled, unlike the liquid-cooled TZ racers, had a distinguished history of their own. The RD350 was developed from the YR5, which had been launched in 1970 and in turn traced its design back several years further to the firm’s first 347cc model, the YR1. The engine’s cylinder dimensions and 180-degree crankshaft arrangement had remained all that time.

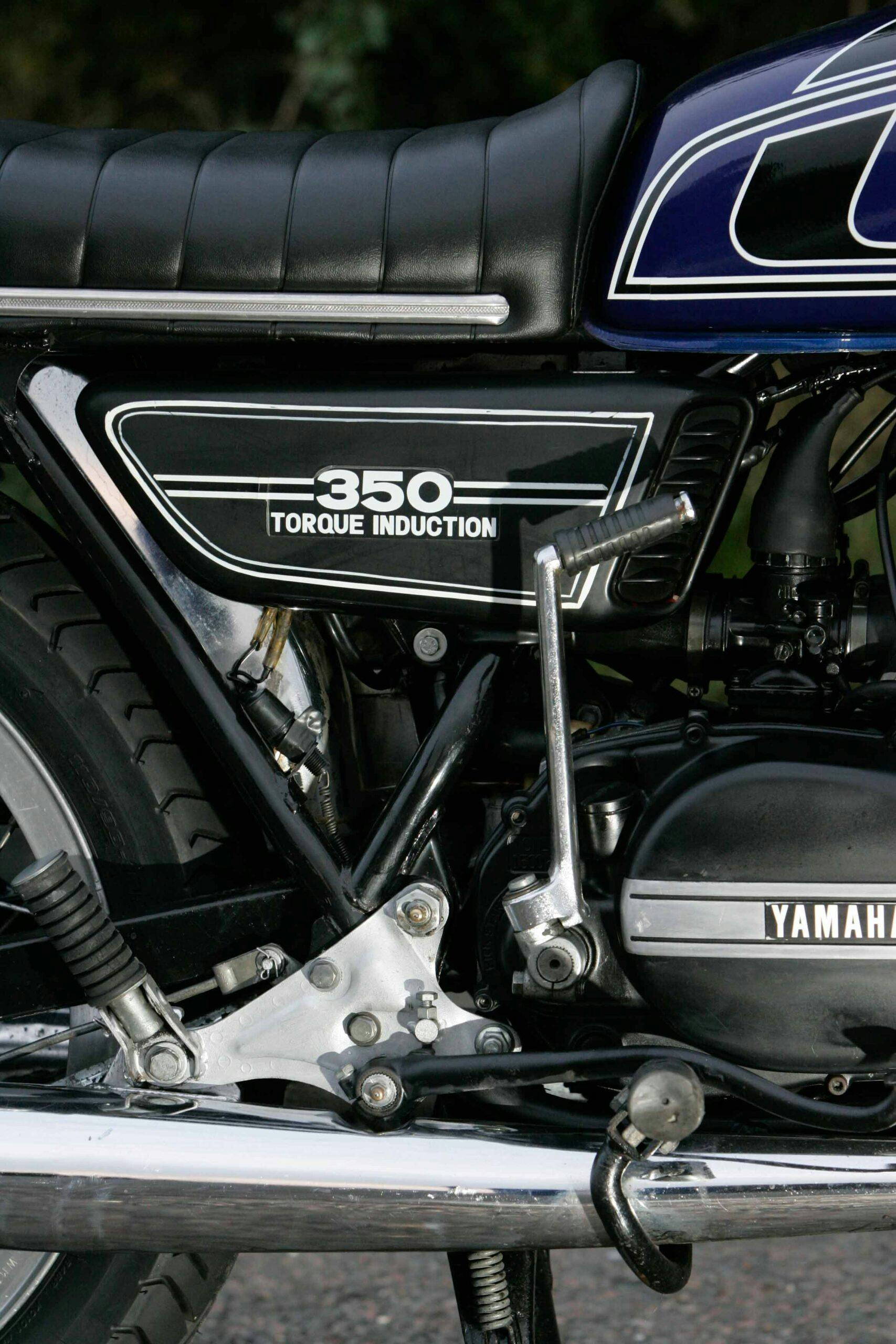

The RD350’s main engine-related innovation was its reed-valve intake system, called Torque Induction by Yamaha. The reed valves, one located between each Mikuni carburetor and its cylinder, improved intake efficiency by reducing the amount of mixture that was spat back.

As one contemporary tester put it, Torque Induction “allowed hairy intake timing without the motor suffering from low-speed indigestion.” This allowed Yamaha to boost top-end power while giving useful performance and cleaner running at low revs. The RD350’s peak output of 38.5 hp at 7500 rpm was a handy three horses up on the YR5’s figure.

The RD also incorporated Yamaha’s Autolube system rather than requiring oil to be added to its fuel by hand, as was still common at the time. In most markets, the bike gained a six-speed gearbox, with the now-familiar left-foot change and one-down, five-up shift pattern, although bikes sold in the UK had the top ratio blanked off.

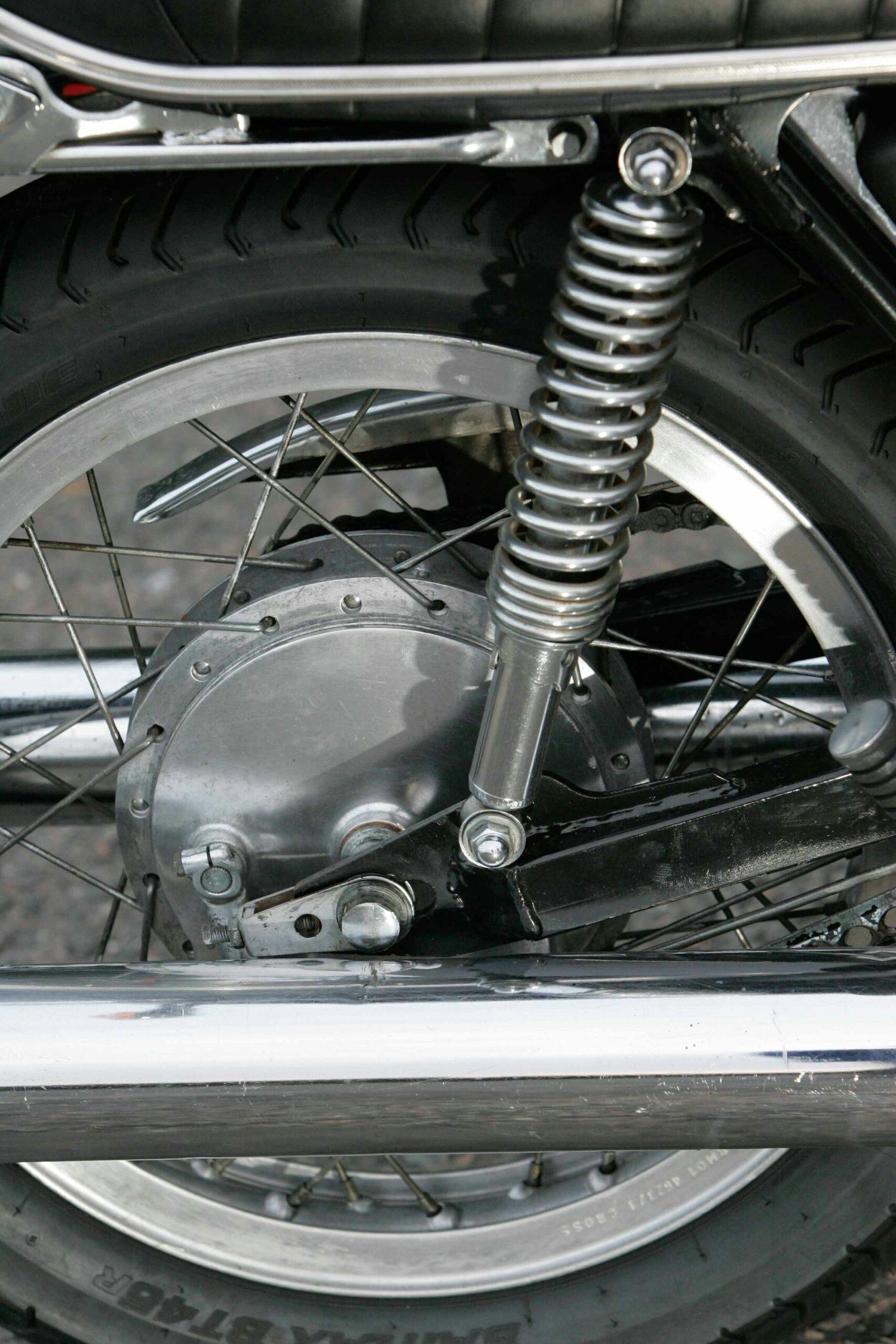

Chassis layout was mostly similar to that of the YR5, based on a twin-downtube steel frame that held typically skinny front forks, plus twin shocks that were adjustable for preload. The main change was the front brake: a single disc in place of the old twin-leading-shoe drum.

Styling owed much to previous Yamahas, including the YR5, but a larger fuel tank, a longer seat, and a black-finished engine gave a more substantial appearance. Although the RD’s raised bars and fairly forward-set footrests offered little clue about its sporty character, it was a lean and attractive machine.

The borrowed 1974 model I rode looked almost new, apart from a couple of minor marks on its blue tank. It fired up easily, requiring just one or two gentle prods of the kickstarter before bursting into life with an evocative blend of exhaust crackle and two-stroke fumes.

My first impression was of how small and light the Yamaha felt, which is no surprise given its short wheelbase and dry weight of just 315 pounds. This might have been a race-developed sports machine, but it was docile and easy to ride. The wide handlebars and generous steering lock combined to make it effortlessly maneuverable in town.

Also contributing to the RD’s ease of use was its smooth low-rev performance, which was notably better than that of its YR5 predecessor. Although the response to a tweak of the throttle at 4000 rpm or below was gentle, the Yamaha pulled cleanly in the lower gears, with no sign of the plug-fouling tantrums with which some of its predecessors had punished gentle treatment.

Not that I let the Yamaha have an easy time for long, because the moment it reached 5000 rpm, the RD350 was transformed. Its exhaust note hardened from a flat drone to an excited zing, and the bike leaped forward with enough urgency to make me tighten my grip on those wide bars. The tach needle flicked round toward the 8500 rpm redline, and my left boot jabbed repeatedly at the gear lever to keep the motor in its power band.

The little twin certainly responded with enough enthusiasm to make me understand why the tester from Cycle Rider wrote that “the performance and acceleration of the RD is nothing short of amazing.” But I didn’t share this impression: “The power-to-weight ratio is so great that if one isn’t careful he will unexpectedly find the front end lofted quite high in the air when accelerating hard in a low gear.” If that tester pulled unplanned wheelies, he must have been mighty sharp with the throttle …

Even so, using all that power sent the Yamaha charging past an indicated 90 mph despite its unhelpful high-barred aerodynamics, and some testers reported 100-mph-plus top speeds, although the true figure was generally just short of that. That high-speed reputation helped the RD350 outsell rivals, including Kawasaki’s S2 350 and Suzuki’s GT380 in most markets.

One slight downer was that above about 6000 rpm, the Yam passed a fair bit of vibration, especially through its seat, which made the engine’s incessant demand for revs tiresome at times. Contemporary reports generally rated the RD very smooth, so either I’m less tolerant than those riders or this bike had understandably got a little rougher in its middle age. Back in the 1970s, more testers seemed more concerned by the two-stroke’s predictable thirst for fuel.

This RD’s chassis had held up very well, and my thoughts on its quick, occasionally over-sensitive but generally stable handling pretty much tallied with comments written when it was new. Its short wheelbase and light weight meant it could be flicked into bends with the merest nudge on those wide bars. And the Yamaha gave a firm, reasonably well-controlled ride without being too harsh over bumps.

That remained true even when it was ridden hard, as the tester from Cycle Guide enthused: “The first time you really stuff the 350 into a tight corner, you begin to understand about its road racing ancestry. You enter the corner wondering if you’re going to make it; you leave the same corner wondering why you didn’t enter it faster.”

I didn’t get quite so aggressive in the bends on this elderly RD, but was happy to make good use of its relatively modern tire combination of Avon front and Bridgestone rear rubber, both of which were doubtless superior to its original fitment. And I was equally impressed by the front disc brake, which stopped the Yamaha abruptly, with no hint of grab.

The disc reportedly even worked well in the wet, unlike many contemporaries, and it combined with the reliable rear drum to give the best stopping performance that Cycle magazine had ever recorded. Contemporary testers also enthused about the high-quality finish, neat switchgear, and even the hinged and lockable fuel cap. Seat comfort was another matter, but for a sporty middleweight the RD was impressively practical.

All in all, the RD350 was brilliantly lively, capable, and fun to ride—this example very much included—I thought, as I followed its headlight beam back toward base on the last leg of my ride. Then the Yamaha suddenly slowed to a gentle halt at the roadside, felled by an elderly battery that couldn’t handle the lights’ demands.

The RD350 ended up being trucked home in disgrace, but that shouldn’t diminish the reputation of a model that fully deserves its classic status. The RD400 that followed it in 1976 was even stronger and more powerful; the liquid-cooled RD350LC of five years later was better still. But there’s something very special about the air-cooled RD350—the bike with which Yamaha’s two-stroke twins came of age.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I don’t remember a YR 350 but the Yamaha R5 (1970-1972)was amost the same bike with a piston port engine (no reed valves) and a 5 speed trans. Also, by 1970 I don’t think there were any Japanese two stroke street bikes that were not oil injected. I owned both and worked on a lot of these and I think the R5 got a bum deal from history as it was just as fun to ride only with just a little less power.

Why was 6th gear blanked off in Britain?

Had a 74 late 70’s sold because of family things. One of the few things I wished I could get back. Running through gears virtually couldn’t shift fast enough.

I can’t remember exactly the year I got one,but that sucker put many bigger bikes in their place. It was the RD400 version. This one had been rode hard and put up wet. Rubbed on it alot and changed out bent or rusted stuff with what we could find, borrow, steal or beat on to make fit. That’s the summer I learned bailing wire technically is a structural member of a frame with enough wraps if you can get it tight enough. With new tires and brakes, and lowered bars it took on a life of its own . Next up were the expansion chambers that came second hand from a security gaurd I worked with. He raced on weekends and introduced to me the dark art of “fiddlin’ wit dos cob raiters”. It’ll make sense when you say it right. After that, you had to be aware that this bike could be a handful. Very much a oil injected 2 stroke gasoline powered on off switch of power that made the girls giggle and little kids cry while the old men cussed as you tried your best to be the hero that machine was allowing you to imitate. Yeah…it was that badass of a bike…loads of fun and excitement. Still got that sucker down in the garage. Think I’ll drag it out,start spinning wrenches and clean that dented purple tank and see what happens. Shout out to Derrick,thanks for selling it to me in the ’70s and Mr. Crowley for the chambers and carb fiddlin’.

Where have you been ?? The motor cycle world has said many times over that the Honda CB 750 IS the motorcycle of the 70’s that change motorcycling forever. In line 4 cylinder motor was copied and improved on by every company that made motorcycles.

I had an RD 400. I called it my chainsaw on steroids. The bike looked brand new when i aquired it and I took care of it, never wet, always inside. It developed the clutch fork issue which is supposively common. I knew if I took it apart I would likely ruin it. I always worry about taking things apart and not finishing them pronto. I elected to sell it to a collector and moved to a, ” at the time” new Hyabusa. Like my cars, I sometimes miss the old schoolness but then….

The 1979/80 RD400s were the pinnacle of the air cooleds. They finally moved the footrest brackets above the mufflers, ram air cylinder head and a bullet proof power plant. Then along came the liquid cooled models, and that was that.

I had a 1969 350 and absolutely loved it. It was my first bike and I rode it ,rain or shine for four years until someone made me a deal I couldn’t refuse. A 69 350 Yamaha for a 1968 750 Norton Atlas. Now ,I’d trade my Mercedes for that 350!

I owned 2 R5Bs in the early 70s What is the best way to find one for sale Ronald Dyer

Looking for an r5b or a rd350