The Hellrider’s aircraft V-8 bike is much more than a racing relic

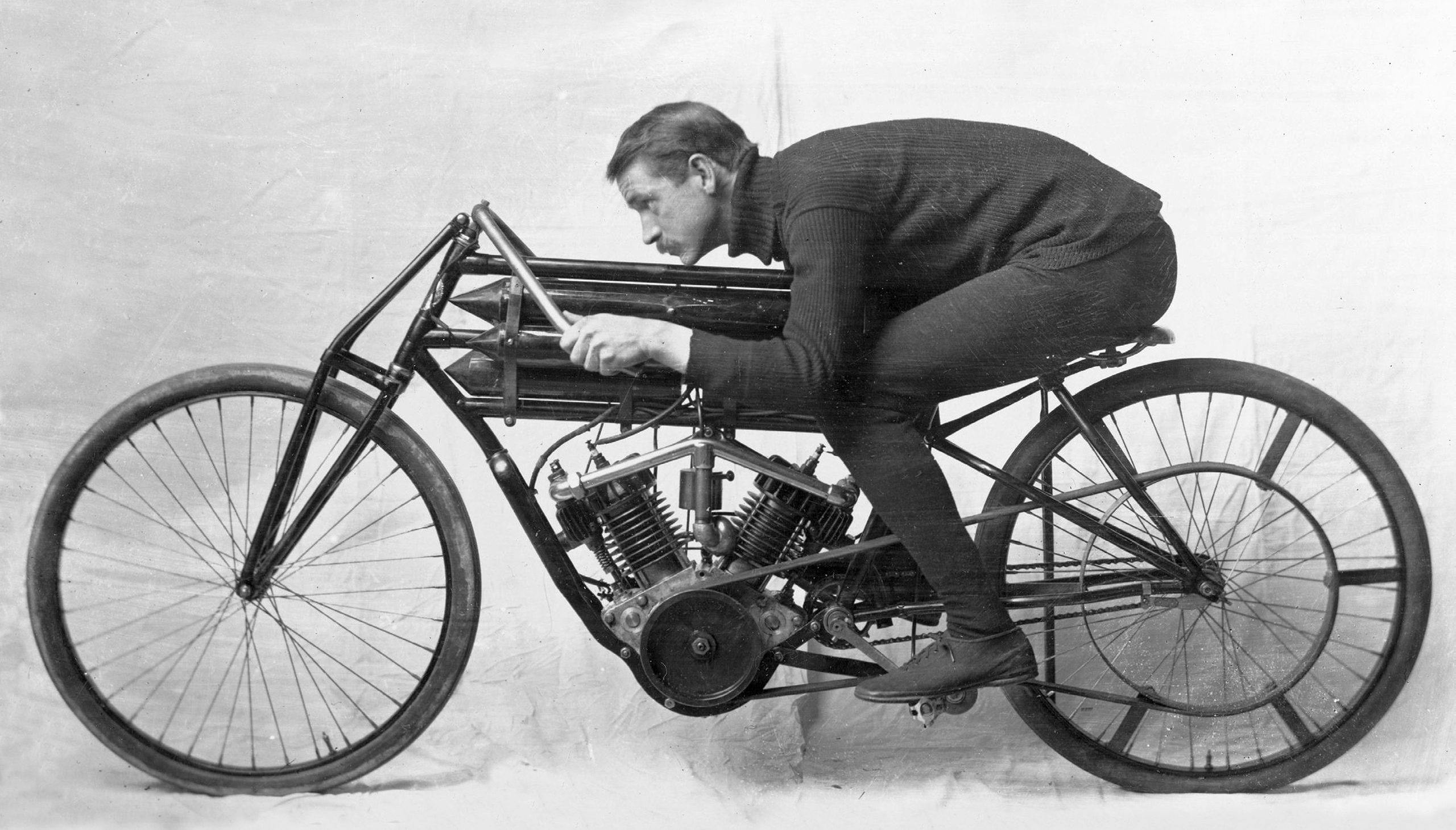

Relics of the early age of the automobile can often appear fusty and uncharismatic, like low-velocity dowager aunts. Tall tires and boxy bodywork seem as anachronistic as watching a magic lantern show or wearing spats. The Curtiss V8 motorcycle, now living in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, looks exactly like what it is: insanely dangerous.

In the years before the first brick was laid at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, America’s temple of speed lay to the far southeast, in Florida. There, on the flat, sandy beaches near Daytona, pioneers of internal combustion vied for the title of fastest in the world. It was a sport for the very wealthy, the first land speed records being set by an heir to the Vanderbilt fortune. Spectating was free, however, and huge crowds gathered at what became known as the Florida Carnival of Speed. Thus, in January of 1907, thousands watched as a man nicknamed “the Hellrider” arrived straddling his improbable steed. Though technically a motorcycle the Curtiss V8 was an aircraft engine on two wheels.

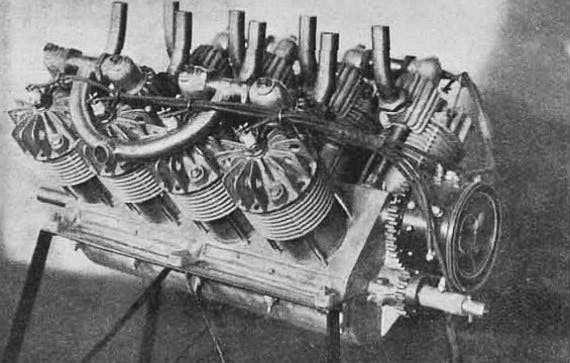

The spidery frame is more bicycle than motorcycle, and more than half the weight of the contraption is made up by the 4397 cc 90-degree V-8 engine. With an individual carburetor for each bank of air-cooled cylinders, the engine produces roughly 40 hp—twice what the first Model T had on tap in 1908. Power is transmitted to the rear tire by a saw-toothed direct-drive gear. There is no suspension to speak of. A single brake provides all the stopping force of a mild headwind.

Imagine, if you can, throwing a leg over the sprung seat of this device and grasping the long, divining-wand handlebars. No clutch means the bike must be push-started, the gear teeth of the direct drive system spinning inches from your left foot. Would you feel safe even at 60 mph, given that the tire technology of the day offered little confidence that it could even put down the V-8’s torque? Could you summon the bravery to crack on towards 100 mph, with the hard-packed sand providing only modest traction?

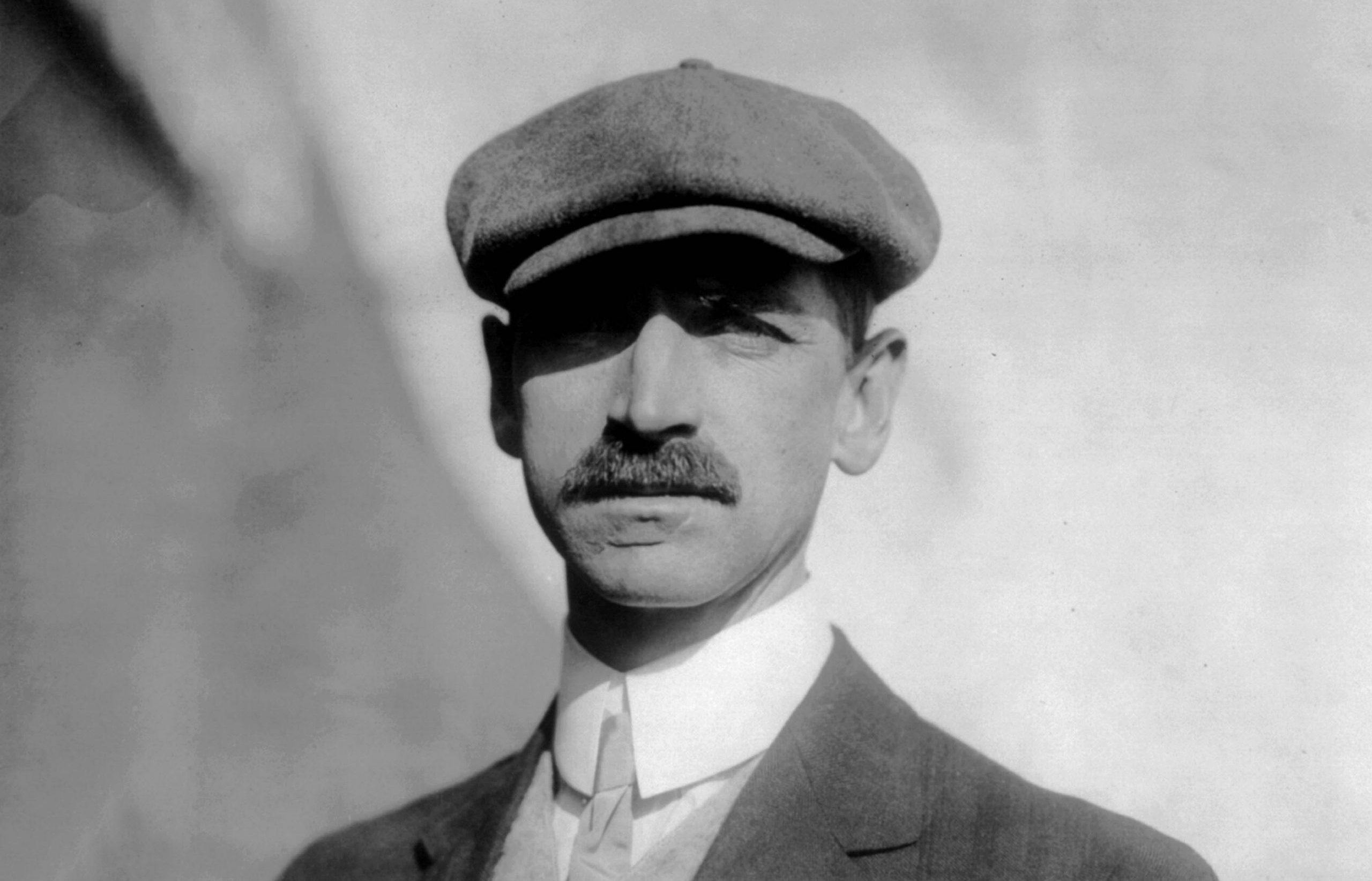

The Hellrider, Glenn Curtiss, did all that and more. Then just 28 years of age, he crossed the line for the measured mile with the bike’s throttle cranked open as bystanders looked on. The next 26.4 seconds must have seemed like a lifetime as his vision blurred from the speed and brutal vibration. When the stopwatches clicked off at the end of the flying mile, some quick math determined that he had achieved an average speed of 136.36 mph; Curtiss had just gone faster than anyone else on the planet, up to and including record-setting aircraft and trains. He was the fastest man alive.

He still had to stop, though. It took two miles for the bike to coast to a halt, at which point—apparently unfazed by the experience—Curtiss turned and then began a return attempt. The repeat run was more … dramatic.

Even if you are not a historian, the name Glenn Curtiss might be tickling a neuron; maybe the name “Wright” helps pull the mental thread? Born in 1878 in eastern New York state, Curtiss was at the forefront of American aviation. He was a contemporary of the Wright brothers, with whom he had a bitter conflict involving patents, and he made many pioneering test flights in theAerial Experiment Association “June Bug” of his own design. To wit, Glenn Hammond Curtiss was the name written on U.S. Pilot’s License #1, received ahead of the Wright brothers by alphabetical order. His pioneering flight of the June Bug was covered by a film crew, and thus he became the first pilot to appear in a movie. For his work in developing seaplanes and aircraft capable of taking off and landing on military vessels, he is considered to be the father of naval aviation.

But before the first Curtiss JN-4 “Flying Jenny” biplane took to the air to train the then-nascent U.S. air power, Glenn Curtiss was the man to beat on two wheels. Hammond was his proper middle name, but two Indian Motorcycle riders inadvertently gave him the name “Hellrider.” At a race, a reporter overheard them say, “Oh hell, he’s here,” and printed a story about it. The name stuck.

First in bicycle racing, and then in motorcycling, Curtiss was again and again a pioneer and champion. In 1903, he won the Riverdale Park Hillclimb, beating the favored Indian Motorcycle team with a 5-hp V-Twin motorcycle of his own design; it would take Harley-Davidson until 1911 to build its production V-Twin. If you wanted a Curtiss designed motorcycle for yourself at the time, it’d cost you $200 for the single-cylinder version and a $75 premium for the V-twin. Adjusted for inflation, the same amount of money would get you a 500cc Honda today.

The budding aviation industry marked the demise of Curtiss’ motorcycling ambitions. By necessity, his engines were lightweight; by design, they were reliable. These qualities soon attracted the attention of fledgling aviators, who Curtiss first dismissed as “cranks.” He liked the money they paid for his engines, but he thought flying wasn’t a serious pursuit.

When a contract came through for two eight-cylinder engines intended for use in a dirigible, he built a third one for himself and went off to the sands outside the Ormond Beach hotel in Florida. He had little idea that his V-8 would eventually power his own trailblazing plane, the June Bug, nor that the engine was about to nearly kill him.

On the return leg of the record run, at 90 mph, the driveshaft let go and began dangerously thrashing around. Curtiss struggled to keep things upright as the engine twisted in its cradle, bending the frame. Incredibly he survived, keeping the bike upright and coasting to a stop without serious injury or death. The bike was too damaged to attempt further runs on the day.

Though unofficial, Curtiss’ record had so many witnesses that he was quickly called the fastest man in the world by the press of the day. The record would eventually be broken in 1911 by the colossal 21.5-liter Blitzen Benz. It would take until 1930 for another motorcycle to best the V8’s 136.36 mph speed, but the Curtiss V8 stands alone as the only motorcycle to ever hold the outright land speed record, and certainly the only such vehicle to outperform any other human-piloted device on the planet.

Curtiss himself would leave the aviation industry some time after the end of WWI, having left his mark on the world of flight. By the time he died in 1930, the various companies he founded had merged with his longtime rivals to become the Curtiss-Wright corporation. By the end of the war, Curtiss-Wright was the largest aviation company in America.

This airborn legacy tends to overshadow his motorcycling achievements, which deserve more attention. If you ever get the chance to see the V8 bike in person, take the time to travel from the Smithsonian’s grounds to the Twin Ring racing circuit just outside Motegi, where you’ll find the Honda collection hall. Currently, Honda is the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world, selling more than 21 million bikes annually. The three-story Honda collection hall is a beautifully laid-out museum, showing the company’s long heritage with many important cars and bikes, both production and racing. It’s a must-visit place for any motorcycle enthusiast.

As soon as you walk in the door, you will see a silver racing special called the Honda Curtiss. On the day that Glenn Curtiss was making his record-setting run on the V8 at Ormond Beach, Soichiro Honda was not yet one year old. Seventeen years later, in November of 1924, a car powered by a Curtiss-designed OX-5 V-8 engine claimed victory in a Japanese race with the young Honda aboard as riding mechanic.

Without actually meeting in person, a kind of torch passed between these two men, influencing the history of motorcycles forever. By working on the Curtiss V-8, Soichiro continued his apprenticeship en route to creating one of the most innovative bike companies in the world, not to mention one of the world’s most successful automakers.

The Curtiss V8 is more than just some dangerous curio of a long-forgotten past. More than an earth-bound antecedent to the man’s eventual impact on the skies. It speaks to the courage and ambition of the man that rode it. It demands from us a question: What might you accomplish, risks be damned?