Stock Stories: 1957 Harley-Davidson XL Sportster

With custom bike culture exploding in recent years, the history and importance of the two-wheeled machines that first rolled off of the production line are often overlooked. Stock Stories tells the tales of these motorcycles.

In 1957, the USSR launched both the first intercontinental ballistic missile and the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1. These actions would ultimately lead to the Space Race, but meanwhile on Earth, that same year, America’s Harley-Davidson released its own history-making machine into the world. It was a new lightweight overhead valve (OHV) twin motorcycle that allowed the U.S. to compete with its British competition, and in doing so birthed one of the longest running models in motorcycle history: The XL Sportster.

Harley’s business survived World War II by providing 90,000 WLA motorcycles to the military. But just a few years after the war’s end, the British were off to a hot start producing lightweight sporty motorcycles, such as the Triumph Thunderbird and the Norton Dominator, which were attracting the attention of the American motorcycle community. Soldiers stationed overseas had acquired a taste for these Brit-style twins, and Harley feared the loss of domestic sales should the Brit bikes make headway in the U.S. market. To attract a wider audience, Harley-Davidson invested resources into two machines. One was the short-lived Hummer, a small-capacity 125-cc targeted at younger city-dwelling riders. The other was a new twin-cylinder side-valve machine called the K Model.

Introduced in 1952, the K Model was Harley’s first attempt to compete head-on with the two-wheeled machines from across the pond. The new lighter and more compact V-twin side-valve had its unit construction with an integrated gearbox—a move away from the traditional big twins Harley were known for. Having previously used predominantly hand gear change, Harley made a notable left turn by introducing a foot gear change on the right side of the engine. With this switch the controls were now in line with the British machines, wearing a configuration that was intended to be ridden on the left side of the road. While it may seem strange for an American company to this route, it’s a reflection of the degree to which Harley was trying to compete with the British. Controls that were designed to make a customer—ostensibly a convert familiar with the British style—feel at home on this sportier machine were also a perfect arrangement for dirt track racing on an oval circuit. For the riders who lean left to negotiate the counter-clockwise track, having the gears on the right side to stop them from digging into the dirt was vital to success in this booming sport.

The K Model was the birth of Harley-Davidson’s lightweight twins, and the KR (racing) model would dominate the AMA races from the mid 1950s through to the 1960s. But by the late 1950s Harley Davidson had spent four years trying to get more power out of the side-valve for the touring customer, and their last attempt was increasing the capacity in the KH model to 883 cc, but this strategy proved counter-productive due to the increase in weight. Instead, Harley-Davidson went on to develop an OHV version of the K Model engine, which became the XL commonly known as the Sportster.

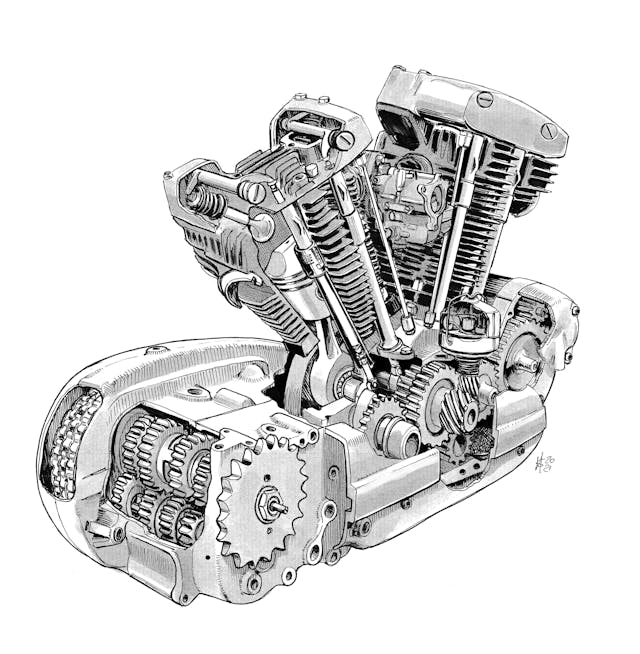

Retaining the same bottom end as the K Model, the XL used the same four-cam configuration to drive the overhead valves—often considered the best valvetrain Harley has ever made. Harley had used aluminum in the heads of its Panhead engines, but customer experience indicated that these engines weren’t yet reliable enough, so Harley opted for cast iron heads on the XL, which weighed in at 495 pounds. The OHV did increase in power, to 40 horses, and in tandem with the four-speed transmission the XL proved itself a real contender within the American motorcycling community. It even built a reputation as an American “sports bike”; the combination of American-made V-twin power and lighter weight meant that the XL was ridable by all.

The everyday and touring rider required more power and sporty attributes than the British machines were providing, which left a window for the XL to claw back some sales. The market share war continued, however, with British 500-cc parallel twins soon importing at a reduced tax rate. (As a slight side note for context, back in 1952 Harley-Davidson fought to protect its brand from foreign imports by requesting that the U.S. government assess a 40 percent tariff to all imported motorcycles. Unfortunately this had a negative impact on the company’s reputation, and the effort was abandoned.)

The original 1957 XL was only produced for a year, and 1983 examples were built. It was a popular machine but it wasn’t long before the X series evolved in accordance with market demand. The 1958 version of the Sportster, the XLC (Competition) came with domed pistons, larger ports, and larger valves. The more serious competition buyer could opt for the XLCH, a high-compression variant often referred to as the “Competition Hot”. As well as performance enhancements, the XLC and XLCH came with shortened or “bobbed” rear fenders and a “peanut” tank—indicators that Harley-Davidson was fully aware of the interest not only in competition-ready motorcycles, but also the fact that people were buying XL models and customizing them. The sporty and compact nature of the engine and frame made the Sportster popular from the start within the custom motorcycle scene. Easily modified into a chopper or bobber, the Ironhead engine has been the showpiece of many a custom motorcycle since its introduction.

While the XL became a popular touring machine, the original Ironhead engine was no good for serious competition due to overheating issues in race conditions; the side-valve KR model, a dedicated race machine, was still favored at the time. The first race version of the XL was the XLR, released in 1962. Designed and built to compete in TT scrambles, the XLR weighed in at 300 pounds and had the potential to produce 80 horsepower if tuned well. At the time of release, the side-valve KR was still dominating the dirt ovals, capable of running up to 750 cc while OHV machines could only run up to 500 cc, and at 883 cc the XLR couldn’t legally compete. In 1968, the American Motorcyclist Association decided to change the ruling for the 1969 dirt season, making a general limit of 750 cc for any valve configuration. Harley-Davidson had already been working on an OHV replacement for the KR but lacked the funds to develop it properly. The company started working on an interim solution but, after failing to produce enough OHV machines to satisfy homologation rules, were unable to enter them into the national championship until 1970.

At the same time, Bill Werner was working in the H-D race department as an engineer. During off hours, Werner began working on his own OHV racer project, making his own tweaks to factory standards. Starting with parts from the Harley XLR and the XL road bike, he modified the pistons and was building his own cams, plus working on the valves and cylinder head, which included locating the plug centrally for better combustion. Breathers, vents, and drains helped to suck air into the crankcase, which in turn pushed through oil, helping cool the typically hot Sportster engine. When completed, this prototype machine wasn’t raced under the Harley-Davidson name but it did provide the HD race department with a hell of a head start to develop a competitor of its own. It was this Werner-bred variant of the XL that evolved into the in famous XR750 racing machine; what started off as an engine for a lightweight touring machine went on to win the most races in the history of the AMA 13 years later.

Not only did the Sportster make an impact on the dirt tracks in 1970, that year’s Bonneville Nationals in August had a number of Sportster-engined machines in attendance. That roster included Leo Payne and his Turnip Eater, which achieved 202.379 mph on average. Every Harley-Davidson machine entered that year in competition set new records in their class, proving that the Sportster engine was a formidable engine indeed. At the same meeting, a Sportster-powered streamliner built by Dennis Manning, Bruce Miller, and Craig Rivera made attempts on the world-speed streamliner record. Even though no records were set during that speed week, their attempts still caught the attention of Harley-Davidson, which wanted to support them in their efforts. Motivation only increased after Speed Week, as the world record was broken by a twin-engine Yamaha machine ridden by Don Vesco at 251.924 mph. In order to bring the record back to American soil, Harley-Davidson supported a return to the salt flats, where the Sportster Streamliner was fettled and tested for nine days before record runs were attempted. Ridden by Cal Rayborn, in a reclined feet first position, the Streamliner achieved a world record of 255.380 mph on October 15. The team was not happy with breaking the record by just under 4 mph, returning the following day and pushing the record up to 265.492 mph—a winning margin of nearly 14 mph.

While the humble XL Sportster had made an impact of sorts upon its initial release in 1957, it was the continual evolution of this lighter-weight V-twin engine that cemented it as a staple in the Harley-Davidson range. It is still produced in America today, and due to its successes in various sports and record attempts, it has truly helped instill the Harley-Davidson name in motorcycle history.

And people want to call Sportsters ‘half a Harley’, ‘piglet’ or (worst insult possible to the macho muttonheads) ‘a girl’s bike’. I’m not a Sportster owner (or fan; I worked on too many of them in my decades in a shop) but I would never disparage their performance, or the enduring appeal of the model line.