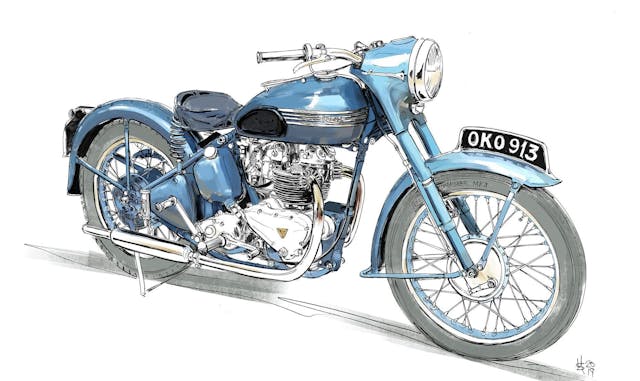

Stock Stories: 1952 Triumph Thunderbird

With custom bike culture exploding in recent years, the history and importance of the two-wheeled machines that first rolled off of the production line are often overlooked. Stock Stories tells the tales of these motorcycles.

By 1949, Triumph viewed the United States as a very important market. Sales of the Speed Twin had already demonstrated that there was demand for lighter-weight machines—lighter, at least, than the typical large twins that Americans were used to. However, the main question about the Speed Twin was its capability on longer stretches of road that were typically encountered in North America.

The Thunderbird rises

Edward Turner, General Manager and Chief Designer at Triumph, had made several trips to the U.S. after WWII, where he received just this feedback. The Speed Twin was light, and just as fast as the bigger native motorcycles, but for longer journeys a 500cc capacity just wasn’t enough. In typical Turner thinking, he looked at what engineering solutions were possible with resources Triumph already had. (Using existing stock and marketing it as a new product was key to keeping costs and development time down.) Boring out the T100 engine out to 649 looked like the best solution, which was perfectly feasible without compromising the integrity of the barrel.

With the development of this new powerful long hauler underway, Turner was looking at how best to market this new machine in the United States. Legend has it that he was inspired by the Thunderbird Motel in Florence, South Carolina. The indigenous iconography of a supernatural bird associated with power and strength seemed like perfect name to ignite the imagination of American motorcycle riders.

Once the development had come to a head, Triumph needed to prove that the Thunderbird could cover long distances at high speed. With the Brooklands track no longer operating, Triumph looked to Montlhéry just outside of Paris as a testing ground. Not only were three Thunderbird prototypes run at the banked track as a publicity stunt, but they were ridden from the Meriden works outside of Birmingham, U.K., to the track and back. At Montlhéry, the three Triumphs all covered 500 miles at an average of 90+mph with the bikes roaring up to the iconic “ton”—100 mph—on the final lap.

From its launch in 1950, with the T6 model denoting a 650cc capacity, the Thunderbird was a great success. It resoundingly achieved its goal of light weight, high speed, and long-distance usability. For this reason, it was used by police departments worldwide, and in the U.K. it was known to law enforcement as a SAINT (Stop Anything in No Time). Again, for the same reason, the Thunderbird became popular with the famous Ton-Up Boys.

In the film The Wild One (1953), Marlon Brando rode a Thunderbird as the rebel rousing gang leader Johnny Strabler. This iconic image brought the motorcycle to the attention of a younger, more style-conscious audience. At the time Triumph didn’t want to be associated with the film, not surprising given that it was banned in the U.K. for 14 years. Once Triumph realized the pulling power of Brando, it capitalized by issuing an all-black version that became known as the Blackbird.

Ironically, by the time the film was finally granted an X-rated certificate, the Thunderbird no longer held the appeal it once did at its outset. Later stylings had turned it to a more commuter-savvy machine. By the late 1950s changes were made to the bodywork to include fully valanced fenders and “bathtub” bodywork, enclosing the rear wheel. These made sense to the British rider who rode often in the rain, whereas the American market had no practical need for such changes. With this less-sporty look, the Thunderbird fell out of fashion. American dealers were ordering more Triumph Bonnevilles, stripping off the fuller body headlight and fenders and replacing them with TR6 versions in order to keep the more aggressive styling.

The Thunderbird would continue to be made up until 1966 with the new Unit construction engine being used from 1963. During this time, it would always be overlooked by customers in favor of the new Bonneville. It is important to remember that the Thunderbird was the first 650cc Triumph to satisfy the American market and paved the way for later models in styling, performance and marketing.

The instrument “Nacelle”

Designed in order to group all the instruments in a visible and usable position. All the instruments are rubber-mounted on the streamlined panel, making them easier to clean and maintain.

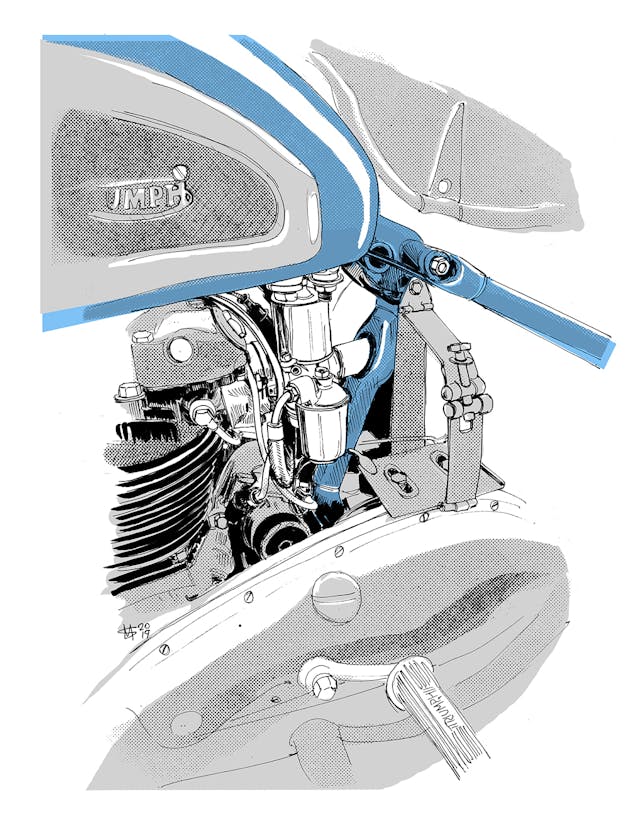

The SU carb

One of the distinguishing things about the 1952 variant is that Triumph decided to switch to an SU MC2 carburetor, chosen for its fuel economy and smooth acceleration. The MC2 was devoid of the power surge present in the Amal Monobloc. The delivery of mixture and resultant power was smooth and constant throughout acceleration.

In order to link the carb to the air filter, a donut shaped lug was incorporated into the down tube, through which the connecting tube passes. This lug distinguishes the Thunderbirds built between 1952 and 1955 from all other years.

Setup of the SU carbs was something that couldn’t be done by staff from the Triumph works; a dedicated SU tuner (Jock West in this case) would have to be hired to come to the factory and tune the carburetors one by one before the Thunderbirds could leave the factory. Ultimately, the necessary expense of this situation proved one of the reasons why Triumph didn’t continue with the MC2.

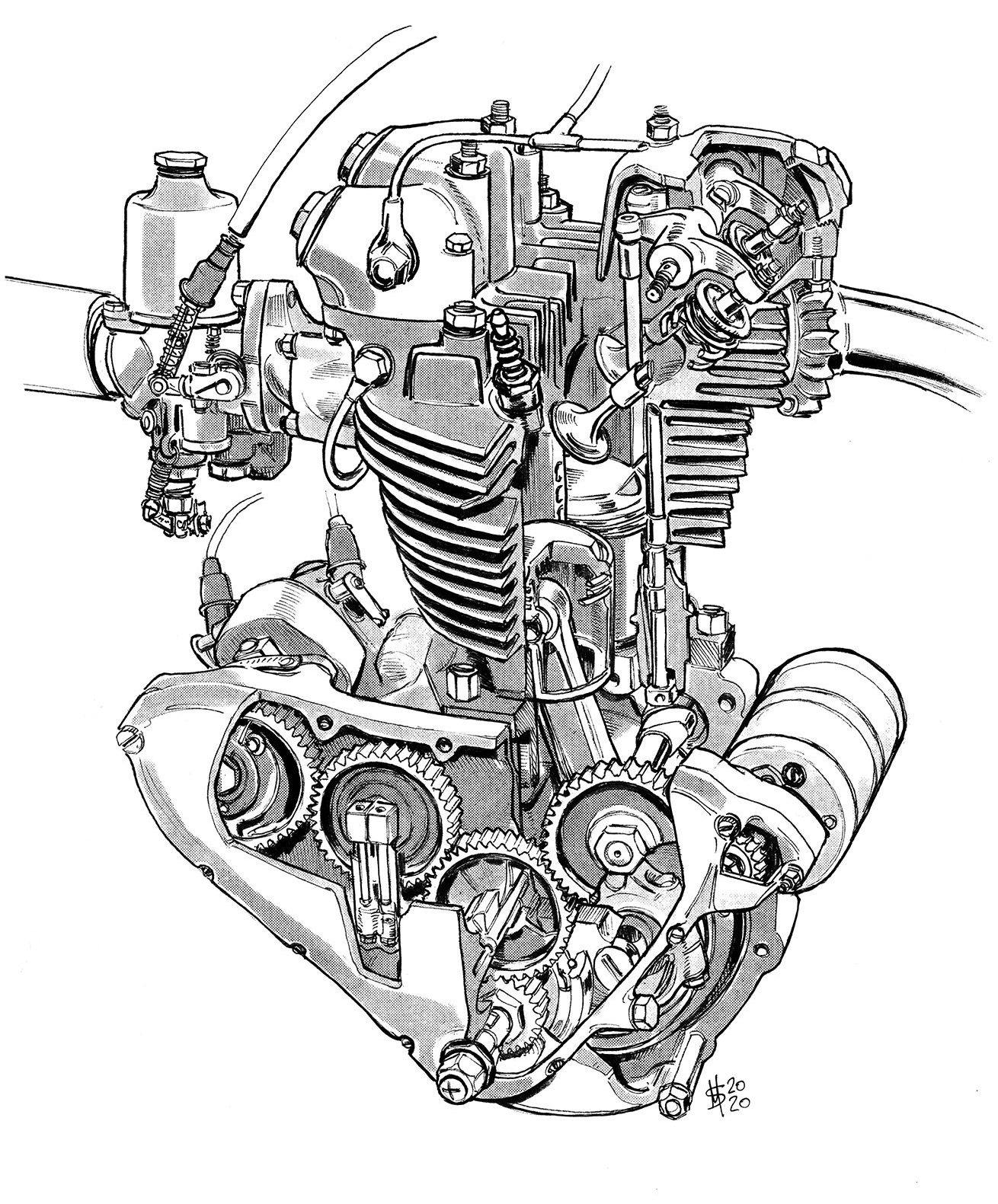

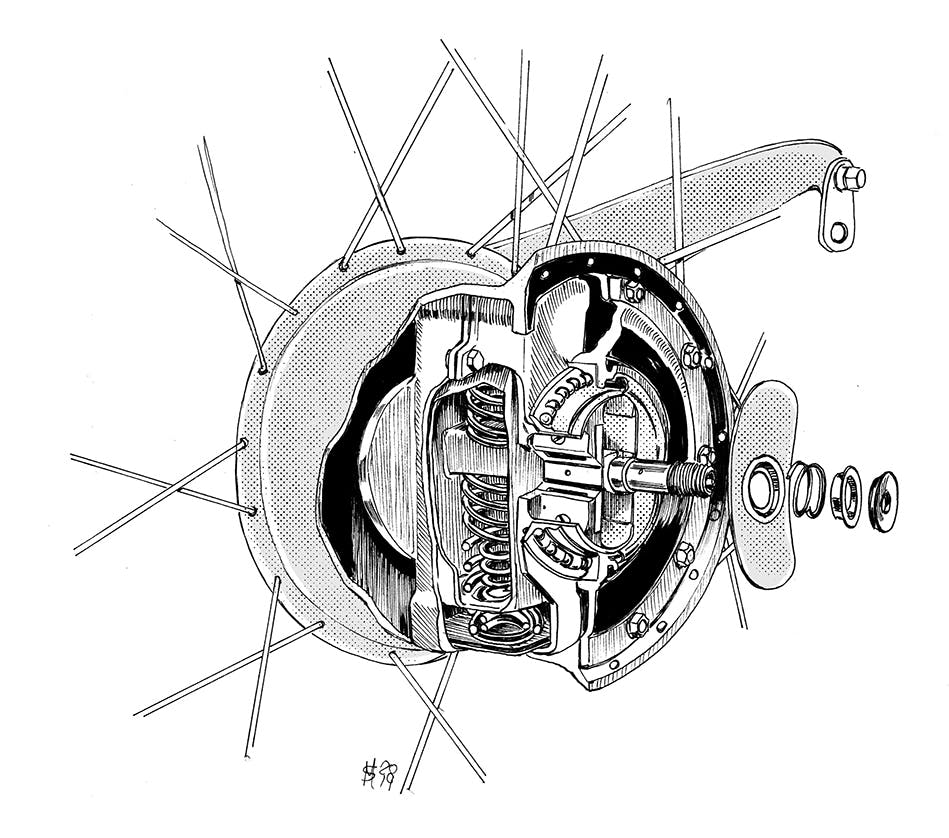

The sprung hub

Turner started working on the sprung hub design in 1938, his intention was to design a simple low-weight and low-cost solution to rear suspension. Inspired by the hub suspension in the Gloster Gladiator made by Dowty, Turner designed a small plunger-type suspension with 2 inches of travel to fit within the rear hub.

The war delayed integration of the hub, originally intended for the 1940s Triumphs, until 1946. A Mark 2 version was introduced in 1951. The sprung hub would be Triumph’s only rear suspension offered for its parallel-twin models up until 1955. Other than adding some rear shock absorption, the sprung hub made it easier to incorporate rear suspension into existing rigid frames and offered an aftermarket choice for existing customers. Turner, clearly, was very in tune with how business was done for profit.

Taking apart a sprung hub is notoriously dangerous due to the compressed springs, and it even has a warning cast into the housing. Mark 1 hubs had a grease nipple but the Mark 2 was built without, as the factory grease was rated for 20,000 miles. Restorers: Beware when taking that hub apart!

Martin Squires is a bike-obsessed and U.K.-based artist. Check out his Facebook, Instagram, and website.

I have a 1952 TBird with Q cams 13 to 1 pistons and flat tappets, still runs good. Also many parts.