Fallen firefighter’s motorcycle is a testament to resilience, 15 years after 9/11

When Gerard Baptiste purchased a beat-up 1979 Honda CB750 for $100 and rolled the restoration project into the Lower Manhattan fire station that housed New York City’s Ladder Company 9 and Engine Company 33, his fellow firefighters laughed.

Baptiste had already been warned that the Honda was a poor choice for his first motorcycle, and his co-workers reiterated that it would cost a fortune to get the thing running again. Ultimately, they were right. It cost everything.

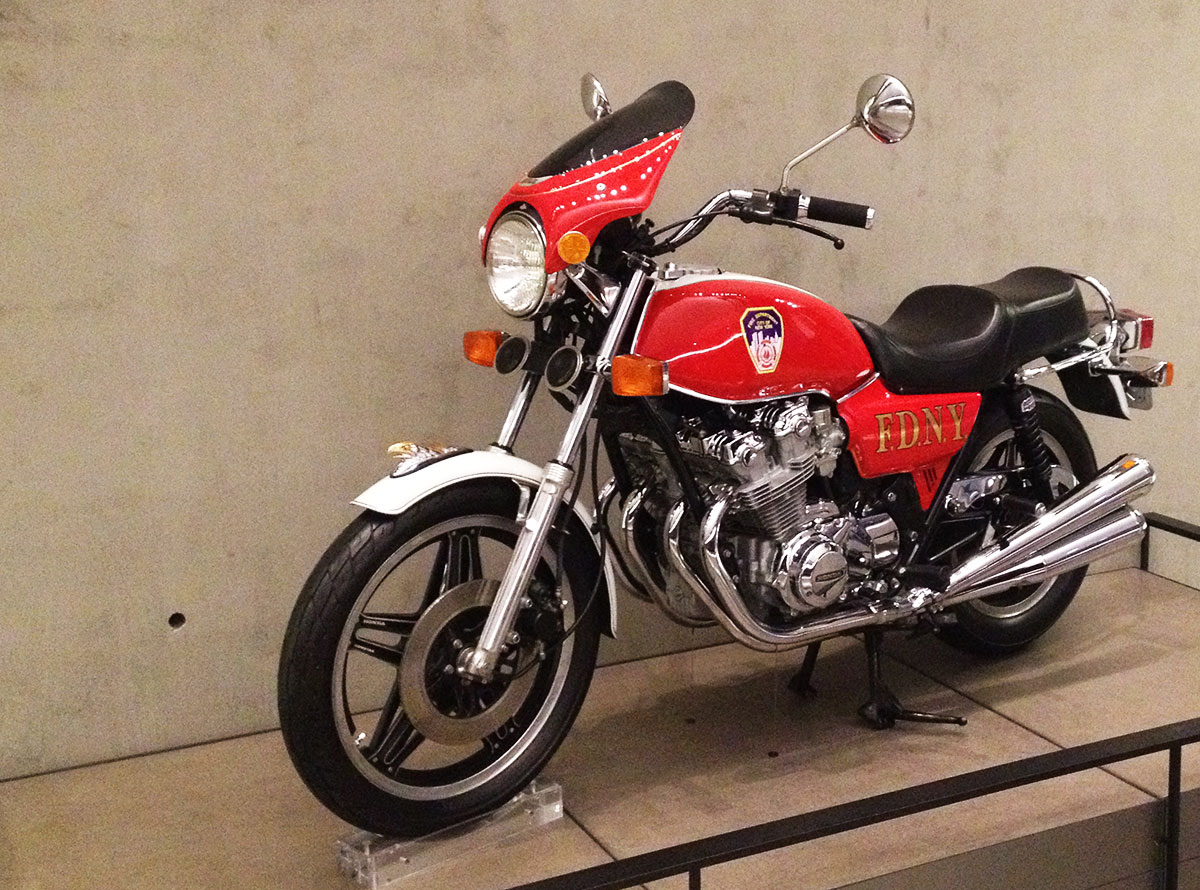

Only a few weeks after buying the bike, Baptiste and 342 of his fellow firefighters were killed in the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. Fifteen years after that fateful day, Baptiste’s restored motorcycle – nicknamed the Dream Bike – serves as a memorial to those who lost their lives in the tragedy. It is on display at the 9/11 Memorial Museum near Ground Zero.

Amy Weinstein, Director of Collections at the Memorial Museum, said she can’t help but look past the shiny red paint and see the bike as it was when Baptiste bought it, “a beat-up, battered, broken-down, non-functioning 1979 Honda motorcycle” that was all but forgotten in the weeks after the attacks as the surviving firefighters struggled to make sense of what had happened. Then, “somehow that heap – that wreck – sparked the imagination of a single journalist,” Weinstein explained in an audio clip on the museum’s website. “His enthusiasm infected the other firefighters, and the motorcycle became a way [for them] to deal with their stress … their trauma … their grief.”

According to the book Motorcycle Dream Garages by Lee Klancher, a pair of reporters from Backroads magazine attended a fundraiser at the firehouse in October 2001 and noticed the bike behind a pile of donations. When asked about it, veteran firefighter Michael Wernick called it “garbage” and said he planned to throw it out. Backroads’ Jeff Kurtzman wrote a column about the forgotten motorcycle, and the response from readers was so overwhelming that Kurtzman’s Backroads colleague Brian Rathjen reached out to Honda and Progressive Insurance, who agreed to help. Spearheaded by the late Stephen Lovas, owner of a New Jersey motorcycle shop, and with the assistance of grieving firefighters, the Dream Bike project began.

Gerard Baptiste, nicknamed “Biscuits” because he handed out treats to dogs near the firehouse, was a five-year veteran of the FDNY. The 35-year-old Army Reservist had just completed an overnight shift when the call came that a plane had crashed into the North Tower. He was inside the building when it collapsed less than two hours later, one of 10 members of Ladder Company 9 and Engine Company 33 to lose their lives that day.

Wernick barely escaped with his life, but like many of his colleagues he struggled with survivor’s guilt. In “American Dream Garages,” Wernick said the Honda rebuild became “a real healing tool for a lot of people, rather than a bike. They wanted to have a connection to 9/11. It became like real therapy for a lot of people.”

The transformation took 15 months. Painted red, the bike’s gas tank carries the artwork of firefighter Kevin Duffy, who included a cross, the number 343, a fire hose and pike pole (“tools of the trade”), helmets with the numbers 33 and 9, and roses representing each of the 10 firefighters from the house who was lost that day. Several members of 33/9 now wear that tattoo, and Duffy’s artwork was added to the boom of Company 9’s tower ladder and the firehouse floor.

Although the Honda received plenty of media attention – including a 2004 documentary by filmmakers John Allison and Tim O’Grady – it didn’t have a permanent home for several years. It resided in Werwick’s garage for a while before he and his wife decided to auction it off and donate the proceeds to an educational fund established for the children of firefighters killed in the attacks. When the bike didn’t reach the reserve price, they raffled it instead. The winner was a woman in California, who gave the bike to a fireman who lost a brother on 9/11. That firefighter gave it back to the Werwicks, who donated it to the 9/11 Memorial Museum, which was in the planning stages at the time.

“It’s such a crazy story, that bike,” Michael Werwick said in the book. “It has such a life to it.”

And honors so many more.