Dresda’s original Triton is a loveable mongrel with race-winning pedigree

Tabloid moral panic over “the youths” is far from a new concept—or a culture-specific one. Tastes in two-wheelers, music, and fashion defined two of Britain’s subcultures of the 1950s and 1960s, the Rockers and the Mods, and those aesthetic allegiances brought the two groups to blows.

Rockers favored motorcycles, while Mods rode scooters, often decorated with multiple mirrors and lights. Rockers dressed in leather jackets and jeans—think Marlon Brando in The Wild One. The Mods were more sartorially refined, with a style you’d more closely associate with Swinging Sixties London. Rockers’ music tastes originated in 1950s rock ‘n’ roll, while mods listened to ska, jazz, and R&B.

While reports were frequently exaggerated, the two groups did clash on several occasions, with fighting, riots, and hooliganism. As tastes changed, so did the subcultures. The papers went elsewhere to vent their outrage, but the fashion and music, and especially the bikes, have never really been forgotten.

The annual “Brighton Burn-up” takes place on the first Sunday of September, when hordes of bikes roar off from London’s Ace Cafe towards the south coast. The intention is to recreate the spirit of ’60s bank holidays, when leather-jacketed Rockers and scooter-riding Mods headed for coastal resort towns, and sometimes fought on the beaches.

The Rockers’ bikes were far more powerful than the Mods’ mirror-festooned Vespas and Lambrettas; typically sporty twin-cylinder models from Triumph, Norton and BSA. Arguably the fastest and most desirable of all was an exotic hybrid: the Triton, whose name came from its blend of Triumph engine and Norton frame.

Back then Triumph made the most powerful engines, notably for the 650cc Bonneville, and Norton’s “Featherbed” frame gave its bikes the best handling. Putting the two together created the ultimate British café racer. The Triton proved its class on the track, too, with victories at many prestigious events.

Nobody knows for sure who built the first Triton, and it’s likely that several individuals did so independently of each other in the mid-’50s. Triumph was reportedly less than pleased. London-based Doug Clark, one early constructor, raced his Triton at Silverstone and shortly afterwards received a letter from the firm, threatening legal action if he continued with the project.

Triumph’s hostility could not prevent the Triton’s steady increase in popularity, which was accelerated in the early ’60s when firms including Dresda Autos of west London began producing conversion kits and complete machines.

Dresda boss Dave Degens did much to make the Triton famous, with his victory in the Barcelona 24 Hour race in 1965. He was swamped with demand after that, and built literally hundreds of Tritons. He also produced large numbers of his own frames, similar to the Featherbed, around which owners assembled bikes of their own.

Demand for Tritons faded in the ’70s (although Dresda went from strength to strength, building frames for Japanese bikes including Honda’s CB750). But as classic motorcycling became popular in the ’90s the Triton made a recovery. Degens, now 83 and still working with long-time business partner Russell Vann, has been busy ever since.

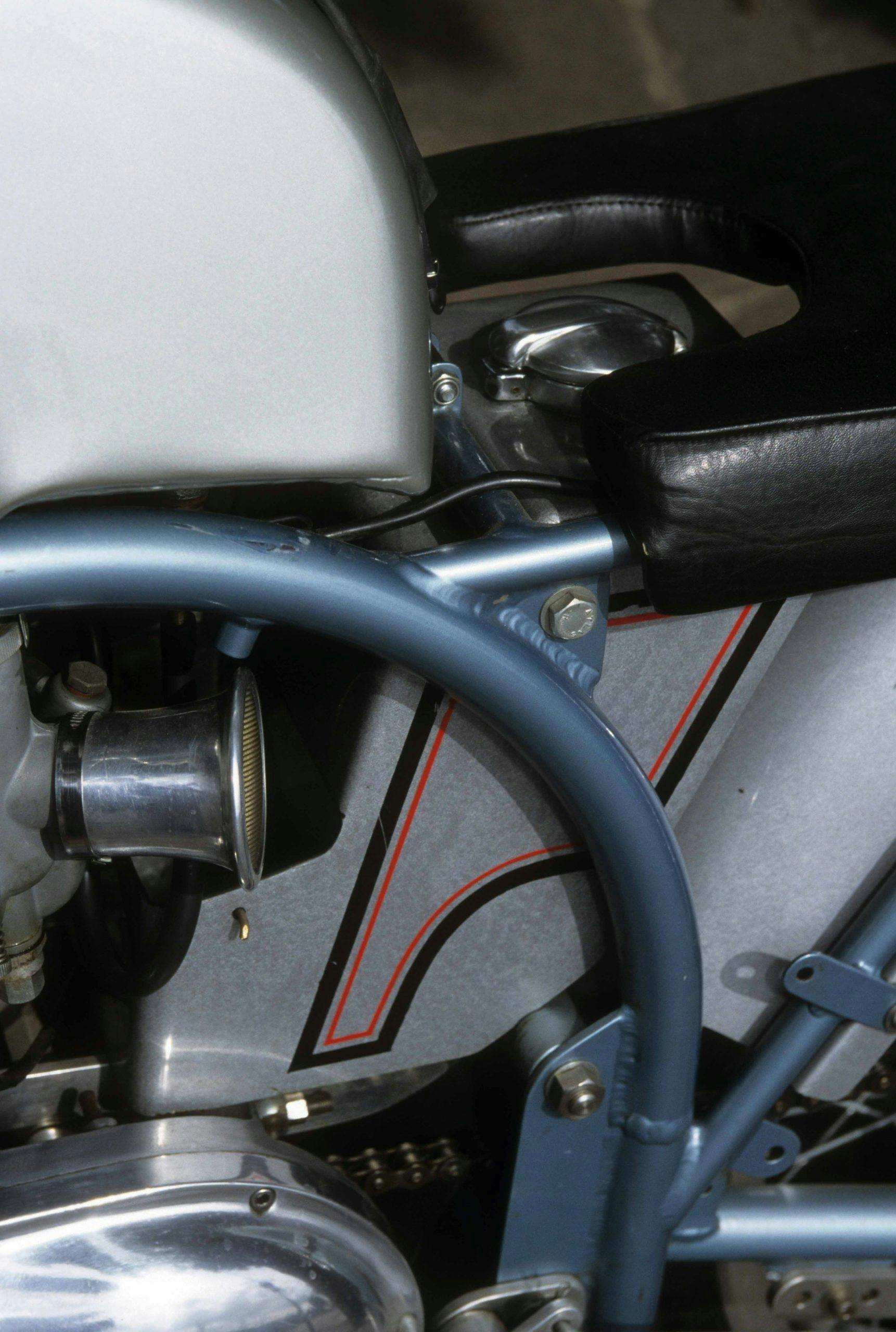

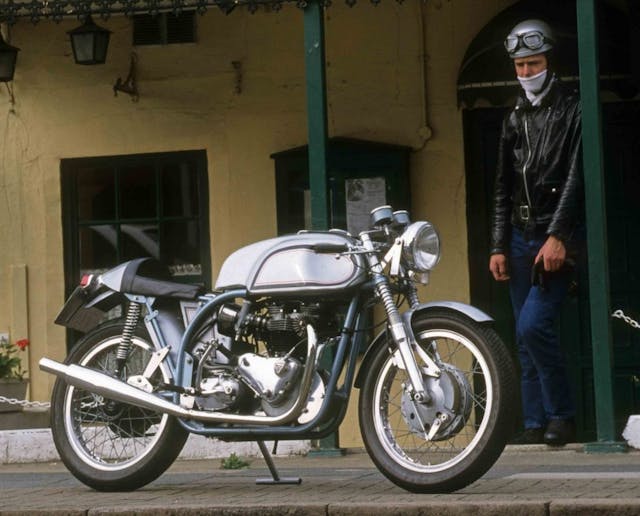

The classical Triton look is unchanged, featuring an aluminum petrol tank, low clip-on handlebars and rearset footrests. At its center is Triumph’s parallel-twin motor, surrounded by the distinctively curved steel tubes of the famous Featherbed frame, so named in 1950 after Norton works racer Harold Daniell had described his smooth-handling bike as like a feather bed to ride.

If the secret of the Triton’s success was that it combined the best British engine and chassis, it’s also true that much of the Triton’s appeal has always been its lean and simple style. Not that any two Tritons are ever identical, any more than was the case in the ’60s.

Engines can range from early 500cc “pre-unit” devices to later 750cc unit-construction (engine and gearbox all in one) twins. The choice of frame includes narrow Slimline and earlier Wideline Featherbeds, plus original Manx racebike frames as well as Dresda’s reproduction. Tritons feature a variety of tanks, seats, suspension parts and exhaust systems; some even have fairings.

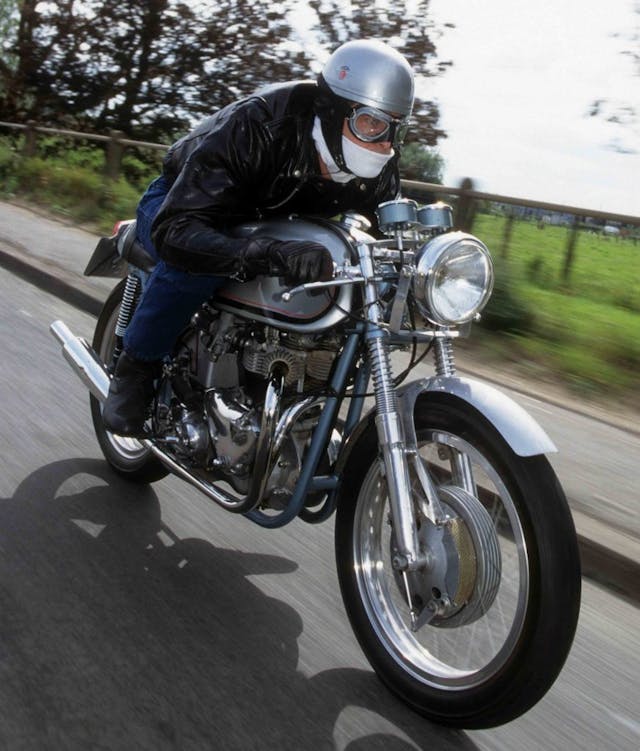

Whatever the bike’s specification and level of tune, the rider’s view is likely to be much the same. From the low seat you reach forward across the shiny tank, grip the low clip-ons and glance down at the pair of black-finished Smiths instruments set in a polished aluminum plate.

The footrests are high, but not especially rearset by modern sports bike standards. The twin Amal carburettors require tickling; pressing a button to get the petrol flowing. Then you fold up the right footrest and kick to send the engine into life with a crisp bark from the two-into-one exhaust.

The Triton I’m riding here is fairly representative of the bikes that Dresda have built, but it is far from a normal roadster. This, Degens said with understandable pride, is the very machine that he rode to victory at Barcelona’s Montjuic street circuit in 1965.

After that historic win Degens raced the Triton a few more times, then sold it and heard nothing more. About 30 years ago he rediscovered it, stored in someone’s loft. He bought it back, restored it and still owns it, although knee problems have stopped him riding it in recent years.

Despite being rebuilt to original specification, the 650cc Bonneville motor was not in a high state of tune, due to its former racing requirement to run at high revs for 24 hours on poor-quality petrol. Its low compression ratio meant the Triton fired-up easily given a swing of the kick-starter.

It pulled away effortlessly, too, although a generous handful of revs was required due to the four-speed former racing gearbox’s very tall first ratio. At least this allowed me more time to remember the unfamiliar right-foot, down-for-up gearchange pattern before selecting second.

Roaring around the roads on this piece of two-wheeled history was great fun, not least because of the punchy performance of the Bonneville motor. At low and medium revs the Triton felt nicely loose, pulling crisply to about 5000rpm without too much of the vibration traditionally generated by British parallel twins.

The Triton was making about 50 hp and showed a fair turn of speed when revved harder, its acceleration above 6000rpm sending the bike thundering (and by now shaking) towards a top speed approaching 120 mph. But the bike’s competition background—more specifically its racing-specification camshafts—showed up in a flat-spot around 5500rpm. Degens recommends softer standard cams for roadgoing use.

There were no such compromises in the chassis, which in this bike’s case was based around the Featherbed frame from a single-cylinder Manx racer. For Triton use, Dresda modify the Norton steel tubes by altering and removing brackets, and adding a rear subframe.

They also fit new shocks and overhaul Norton’s Roadholder front forks. The standard internal springs are often replaced by coils outside the legs, and damping rates are typically reduced to give a smoother ride.

This bike’s wheels were in traditional 19-inch diameters, but Degens recommends 18-inch wheels because this allows a fatter rear tyre. Despite its narrow rubber the Triton’s roadholding was reasonable and its handling very stable, thanks in no small part to the rigidity of the sturdy Featherbed tubing.

The suspension took enthusiastic cornering in its stride and also did a good job of soaking up bumps, despite the aggressive riding position and thin seat. The only real chassis weakness was the front drum brake, which was feeble despite benefiting from the Triton’s light weight of only about 160kg.

Overall, this old warrior’s performance was sufficient to make it a wonderful companion for an afternoon blast—whether locally or on a burn-up to the coast. It drew plenty of admiring comments when parked, too, and no wonder. The Triton is essentially a mongrel but its look, racing record and café racer reputation give it a charisma that few pure-bred classic bikes even approach.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

***

1965 Dresda Triton

Price: Project, £5000 (~$5680); nice ride, £7500 (~$8520); showing off: £10,000 (~$11,360)

Highs: Speed, handling, café-racer cool

Lows: Wrist pain at slow speeds

Takeaway: Classical combination still rocks

—

Engine: Air-cooled parallel twin

Capacity: 649 cc

Power: 49 hp @ 6500 rpm

Weight: 353 pounds without fluids

Top speed: 115 mph