Tanked up: Learning to make aluminum fuel tanks with Tab Classics

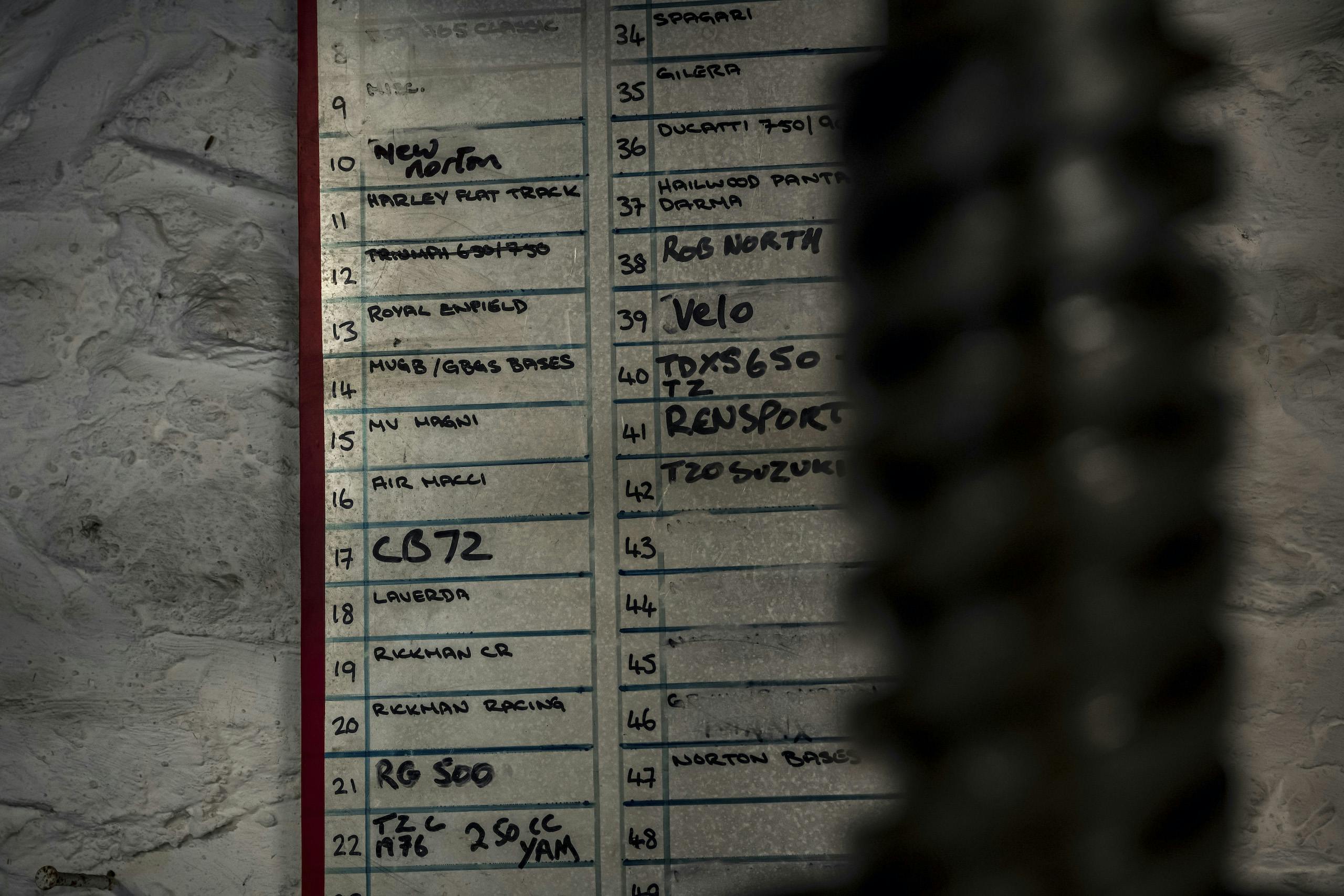

At Twr Gwyn Bach, a small cottage workshop in mid Wales, three highly skilled craftspeople turn an apparently humble twenty-quid sheet of aluminum alloy into a beautiful work of art. Welcome to TAB II Classics, where engineering meets sculpture, and handmade fuel tanks are crafted. Husband and wife Richard and Aline Phelps, together with master welder Mark Purslow, make motorcycle tanks. Tanks for Tritons, Seeleys, Suzuki RG500s, Ducatis and dozens of other bikes.

This story originally published on Hagerty UK.

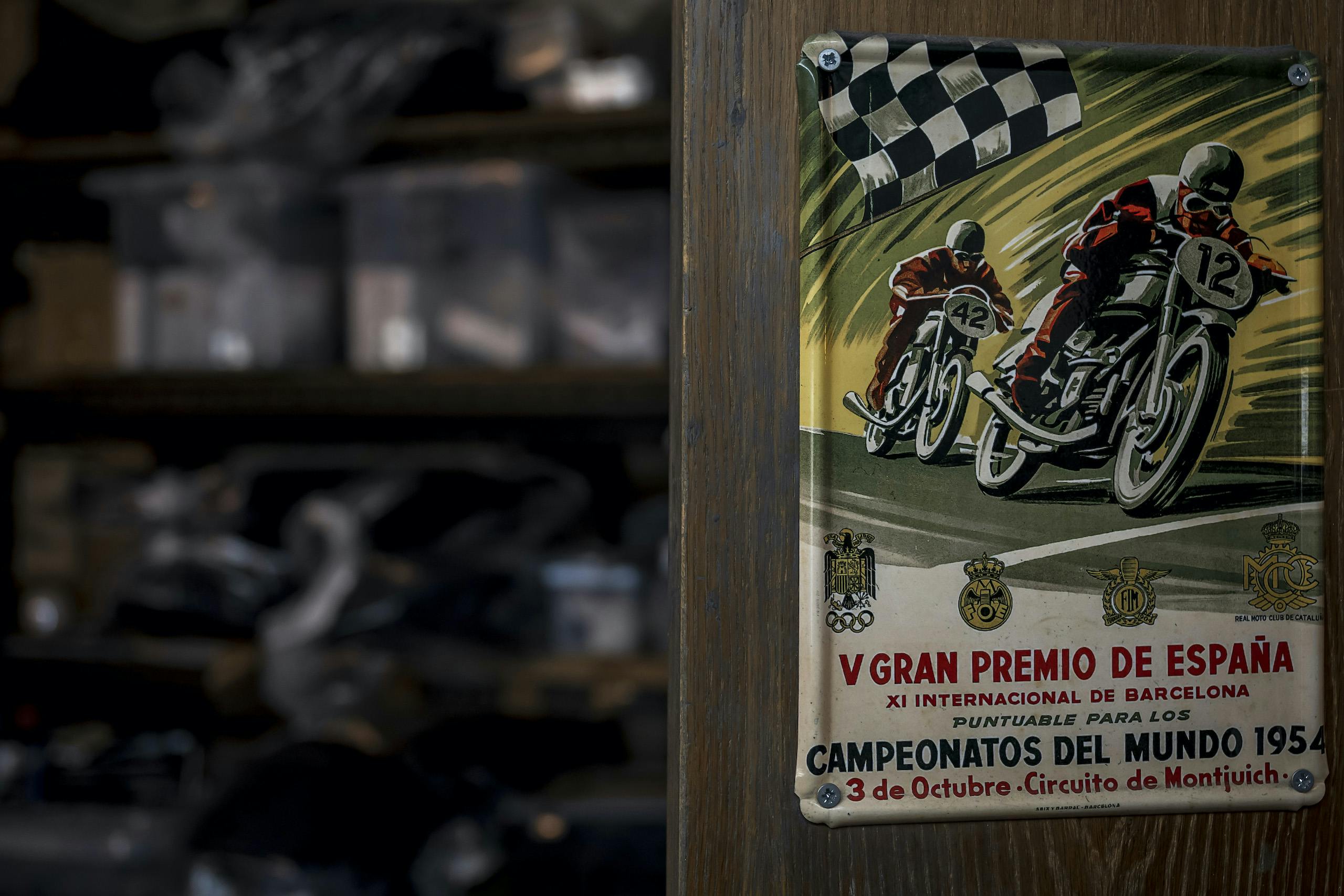

Contemplating slotting a Harley Sportster engine into a Norton frame? You’ll be needing to visit TAB II Classics for a Slimline fuel tank or, if you’re wanting your special to be a real one-off, TAB will make you a bespoke tank either from your design or using their own vast experience.

The TAB in the company’s name comes from the initials of Terry A. Baker, a keen amateur motorcycle racer who in 1972, unable to find a suitable tank for his Honda K4 race bike, decided to make one from scratch. As often happens, other riders wanted Terry to make tanks for their bikes and a business was born. Baker died in 2010 but fortunately for the motorcycling community his daughter Aline, who had grown up around motorcycles and spent her younger years hanging around her dad’s workshop, took over the business with her husband Richard.

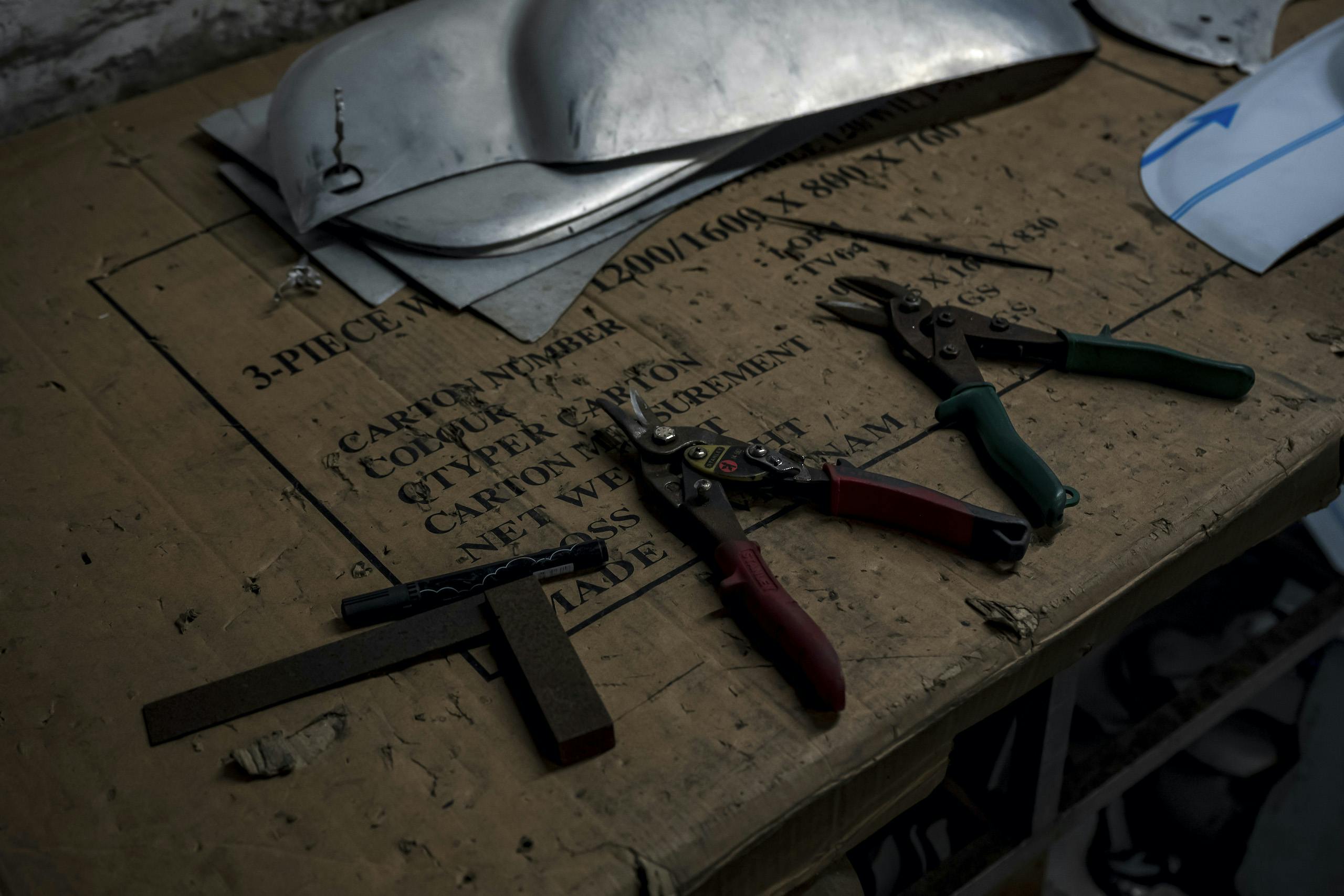

“It’s not very grand here,” Richard Phelps explains, “but we’ve given the place a tidy.” Actually, the workshop looks extremely well organized. In a side room there are rows of shelves on which are kept dozens of formers, each one carefully labeled. Made from a mix of sawdust and epoxy, these “soft” tools are placed in a press and are used to form the shape of each part of the tank: generally two sides, a top section and then a base made from two or more separate pieces depending on the tank design.

The piece that comes out of the press is far from finished and will need hours of careful shaping on an English wheel and perhaps several well-placed blows with metal shaping hammers. All three are capable of doing all the processes used to build a tank but in practice each specializes. Aline Phelps is the master of the English wheel. It’s fascinating to watch. One side of a Manx Norton tank has come out of the press with loads of wrinkles along one edge. With just a few passes through the wheel Aline has removed all the wrinkles and the aluminum is now smooth. It looks easy but I know from previous attempts at “wheeling” metal that it isn’t.

This I prove when Aline gives me a bit of scrap alloy to try shaping. I can’t even get the sheet to stay between the rollers; it seems to have a mind of its own. Wisely she doesn’t let me near the tank side that she’s been working on.

When you look at a finished tank, its polished surface gleaming in the sun, it’s hard to believe that you’re not looking at one piece of aluminum because it is impossible to see a join however hard you look. Two reasons for this: one is the technique used and the other is down to the skill of Mark Purslow. I was expecting to see a TIG welder because they create an incredibly neat weld. “The problem is,” explains Aline, “is that a TIG weld is very hard and that means that I wouldn’t be able to roll the weld bead flat in the English wheel; it would have to be ground flat.”

Mark Purslow has been at TAB since 2013. He joined via the Job Growth Wales Scheme but had already learned welding before. Today the 28 year-old is a master at the art. And of course, like the Phelps, he’s obsessed with motorcycles. He races them and won the Manx GP in 2015, riding in the Lightweight class.

“I make my own filler rod for welding from scraps of the same 1050A H14 sheet that’s used for the tanks,” explains Purslow. “We use 1.5-mm thick sheet for the tanks, which is the metric equivalent of 16 gauge, and 2-mm for oil tanks and seat bases.”

I’ve always been fascinated by welding, especially gas welding. Although Aline Phelps is master of the wheel and Purslow of the torch, the two work together when it comes to joining sections together. First Purslow tack welds the pieces together as Aline bends and manipulates the two sections while Purslow dabs the rod. She’s remarkably brutal with the metal as she bends it but thousands of hours of experience clearly tells her what she can get away with. With the side and top of the tank neatly tacked together Purslow deftly and smoothly runs the weld, stopping in places and then coming from the other direction so that the heat can dissipate. I’ve got to give this a go.

An expendable couple of pieces of sheet are found and Purslow sets up the torch with the correct mix of acetylene and oxygen to create an almost white cone of heat. My first attempt at tack welds is a bit hit and miss: a combination of plops from a pigeon that had a very hot jalfrezi the night before, and holes where I have held the torch in the same place for too long and have burned right through the metal.

“Have a go at simply running the torch along the middle of the sheet without the rod,” suggests Purslow, “so you can get a feel for the speed that you have go at without the worry of dipping the rod.” Sure enough, my bead of melted metal is much neater and I haven’t burnt a hole. In fact I went a bit too quickly and the heat has penetrated deep enough. With practice though …

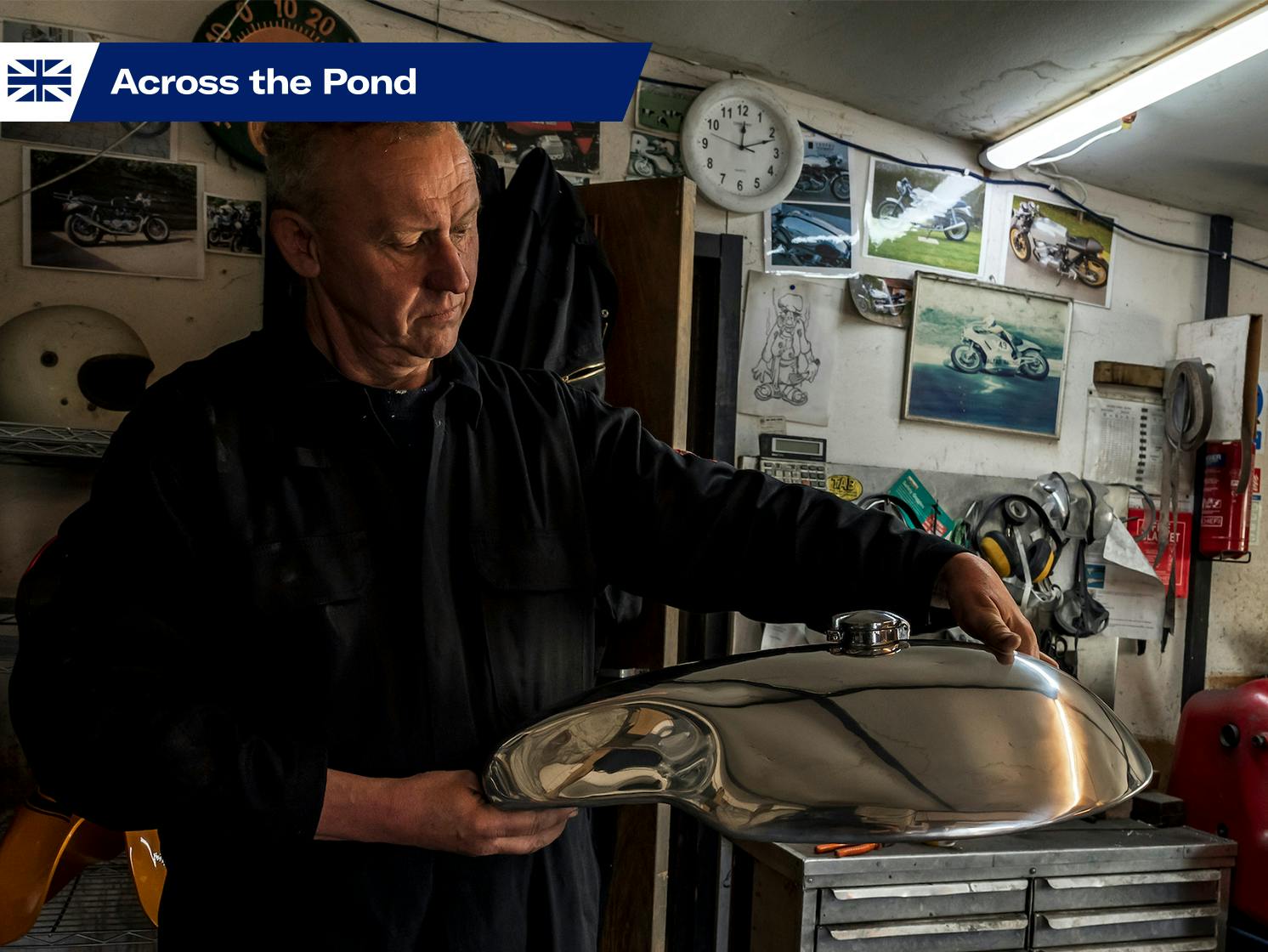

So where does Richard Phelps come in? Richard is front of house at TAB, liaises with customers and does the paperwork. He’s not exactly white collar because he’ll also disappear into a Dickensian room where he does the final polishing and finishing of each tank. It’s a filthy world of dust but it is as fascinating to watch Phelps polish a tank on a buffing wheel as it is to watch Aline bend metal at the wheel and Mark weld it. Richard starts with a rough grade of sanding disc on an air sander and then works through finer grades before moving to the polishing wheel. “Knowing what polish to use and which weight of buffing wheel and concentration of cloth is down to experience,” explains Phelps. What is amazing is how quickly the tank’s surface goes from a dull finish to a deep shine.

It takes between 20 and 30 hours to make a tank; longer if it is bespoke. Ex-racer Steve Parrish has commissioned a new tank for the Yamaha TD2 which was the first bike he ever raced. He’s supplied the original tank for comparison and the new one is sat next to it. Presumably Parrish will ride the bike with the new tank on it and keep the original in case of a tumble.

All of the tanks dotted around the workshops are beautiful but none more so than a Ducati Imola tank, which happens to be Aline Phelps’ favorite, too. “You can tell that it was made using an English wheel, which is unusual in Italy.” No, what Aline means is that she can tell.

The Ducati tank is so beautiful that despite the fact that I don’t have a 900 SS upon which to put it, I am very tempted to buy one as an objet d’art for the sitting room. It would look spectacularly cool if one half of it was painted in that lovely blue and silver of Paul Smart’s Imola 200-winning 750 SS and the other side left in its polished alloy finish. This is not a daft idea because TAB II Classics wants only the reasonable sum of £550 ($777) plus VAT for an Imola tank complete with filler cap and fittings.

It is possible to buy tanks from India and China that are considerably cheaper, but then you’re taking quite a risk. What if the tank isn’t a perfect fit? Currently at Twr Gwyn Bach (in the Welsh village of Tregaron) is a Seeley-framed Honda CB750 owned by a Seeley fanatic who has a collection of ten bikes. He’s wisely brought his bike along to make sure that the tank perfectly fits his frame. He’s had to come a long way, but it’s a shorter drive than it is to Delhi or Beijing. And good luck with commissioning a one-off design from a company in a different time zone run by people who have probably never seen any of the bikes they’re making tanks for.

Not that the Phelpses and Mark Purslow need to worry too much about demand. The whiteboard in the office is full of orders from customers from Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. as well as mainland Europe. And then there’s the hipster market and the cult of custom bikes that is showing no signs of slowing down any time soon. In fact, I reckon that more and more youngsters will discover the thrill of biking and the even bigger buzz of creating your own machine. There are many jobs on a motorcycle that are straightforward and that can be tackled by an amateur. Building a fuel tank from scratch isn’t one of them. I know, I’ve just tried it.