Why enthusiasts love analog cars

Last year, vinyl records had their best year since 1987. Mechanical watches, tube amplifiers, and even film photography also continue to enjoy a resurgence. Analog tech is clearly having a moment. So why should low-tech cars be any different from records, amps, cameras, and watches?

In point of fact, they’re not—post-1990s analog cars are hitting their stride among a certain subset of collectors and enthusiasts. But what makes for an analog car, and why are people coming to appreciate them? Let’s just say that while the cars themselves may be simple, the answers to those questions are anything but.

There seems to be little consensus on what exactly fulfills the analog definition. The most hardcore enthusiasts will not abide any electronic drivers’ aids, like traction control or even ABS, while the more tolerant will accept those but draw the line at electric power steering, which they consider to be the work of the devil. Where enthusiasts do come together, however, is on the tactile delights of a good, old-fashioned, hydraulically assisted steering rack and, of course, the non-negotiable manual transmission.

Similarly, it’s hard to pinpoint the exact moment when analog cars gained the throwback quality that made them cherished outliers rather than the norm. Just as there was nothing novel about the vacuum tubes in a Carver or a McIntosh amplifier from the early 1960s, there was nothing remarkable about a C2 Corvette of the same vintage lacking ABS or traction control. There was, however, most assuredly something damned unusual about the 2005 Lotus Elise not having power steering, or the 2000 Dodge Viper lacking ABS. Those traits contributed to the Elise’s reputation for driving purity and the Viper’s rawness—even when new—and as a result few can quibble with those models being charter members of the late-analog car hall of fame.

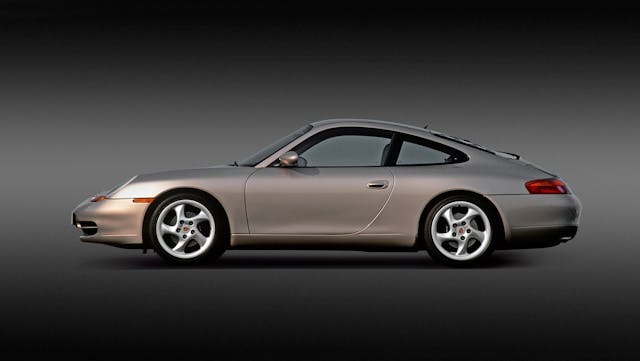

Analog car fans can be incredibly geeky, to the point of near-snobbishness. For example, many single out the 1999 Porsche 911 as the last true analog 911—but it can’t be just any 1999 911. Nope, it has to be the Carrera 2, and not the all-wheel drive Carrera 4. Why, might you ask? Although both cars could be ordered without Porsche Stability Management (PSM), only the Carrera 2 came with an old-school cable-actuated throttle, whereas the Carrera 4 had an electronically controlled one. These folks have been known to split a few hairs.

Regardless, they are onto something. The more that digital-age assists make spirited driving easier—and further disconnect us from the task that got us excited about cars in the first place—the more people seem to revel in cars that lack that technology.

Case in point: two track events that I did a few years apart. The more recent of the two was at Road America in a then-new 991-generation Porsche 911 GT2 RS. The suite of driver’s aids on the car made blistering lap times available to mere mortals and superbly managed the car’s 690 hp. Did you get on the gas a little too soon exiting a corner? No problem, the car knew better: It overrode your hamfisted, premature throttle input until the front wheels were pointed straight. The car’s sophisticated electronics always made you feel like a hero, but deep down, you knew where the magic was coming from.

In contrast, years earlier, the Z06 Corvette I drove had far less sophisticated driver’s aids. It was an unrepentant oversteerer, unwilling to mask the mistakes of an unskilled driver. But, when you nailed all the inputs just so and rocketed out of a corner, your ear-to-ear grin came from knowing that little bit of perfection came from you working with the car. And that’s precisely the appeal. Lovers of analog cars want the visceral thrills—they want to take the risks and bask in the rewards.

Alongside renewed appreciation for driving these cars, the market seems to have jumped on the late-analog car bandwagon. Supercars that fit the analog moniker, like the Ferrari F40 and Porsche Carrera GT, are breaking records, but the trends aren’t just limited to the top of the market.

First-year 996-chassis Carrera 2s are now highly sought-after cars that have increased in value by 74 percent over the last five years. Early Dodge Vipers, after years of fairly static pricing, are firmly on the upswing. Values of my personal favorite late-analog car, the pretty and diminutive Lotus Elise, have followed a similar trajectory. Cars that were in the low $30,000 range a few years ago are now in the mid-forties, and likely to climb further. That’s no surprise—as it becomes more obvious that we’ll never see a new sports car with a curb weight under a ton again, people are flocking to the little British sports car. Simplicity doesn’t come cheap, unless it’s the perfect Elise substitute, the very analog Toyota MR2 Spyder. Don’t tell anyone.

At least as it applies to cars, “analog” is always going to be defined differently based on who you ask. But one thing’s for sure: as our automotive world becomes increasingly digital, the last generation of cars that offered a pure mechanical connection to the road will only grow in popularity.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

it’s an old story..either you drive the car or it drives you;

people like tube amps and vinyl recordings simply for the comforting amount of harmonic, inter modulation and other distortions they introduce just like voluminous speaker cabinets containing multiple speakers and crossovers;

such deceptions are for suckers more than willing to part with ridiculous amounts of money to demonstrate their exclusive club membership;

P. T. Barnum made a fortune off them;

Oh, analog, another word to add to my can’t stand over used list along with paradigm and old school.