The Ferrari of Theseus: Philosophy and a $1.87M Pile of Parts

If you’re a regular reader of this site, you may have seen that we named the sale of a 1954 Ferrari 500 Mondial Series I by Pinin Farina, #0406MD, our most significant of 2023. Ordinarily, an old Ferrari race car changing hands for more than a million dollars would not constitute anything newsworthy in our niche little world. In this case, the car—if you can even call it that—is far from ordinary. It is a twisted mass of bent, dented, and corroded metal, the victim of a racing career, a massive crash, time, and a building collapse amid a 2004 Florida hurricane. As Monty Python would say, “This Ferrari has ceased to be! It is no more! It is an EX-FERRARI!”

The buyer, who did not bid on a parrot, seems to feel otherwise. Yes, it may look like a near-$2M paperweight now, but with at least that much more cash in reserve to pay for the mother of all restorations, this might once again be a 1954 Ferrari 500 Mondial. Even if said restoration involves, as Hagerty Price Guide editor Dave Kinney mused, “every single nut and bolt.”

When most people outside the car world hear about such a plan, they wonder: Is the end product even the same car? Indeed, many people within the car world do too.

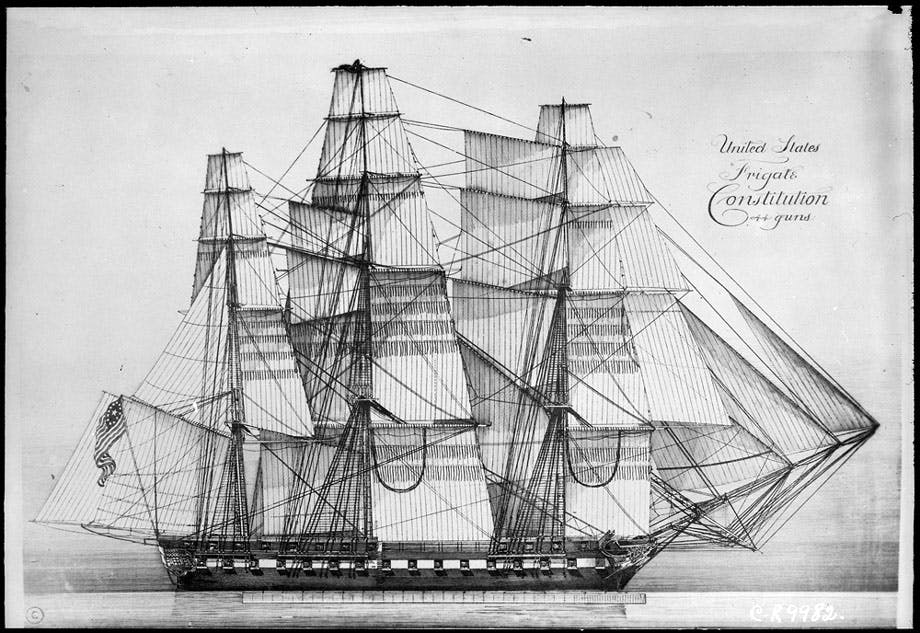

That question got me thinking about a centuries-old philosophical paradox, one that may ring a bell. It’s called “The Ship of Theseus.” Some of the world’s most brilliant thinkers have wrestled with the problem and examined it in various ways, but the crux of the question is fairly straightforward.

Imagine a sailing ship whose best days are behind it—rotting planks, tattered sails, empty bottles of grog, et cetera—that gets a complete and total makeover in which every single component is replaced with identical, shipyard-fresh components. Is it still the Ship of Theseus when the final plank is laid, or is it now… something else?

In other versions of the conundrum, the worn parts are subsequently rebuilt into another ship, producing two ships in total, one new and one old. Which, then, is the real Ship of Theseus? In other versions still, pieces are replaced bit by bit over a period of many years, engendering other questions such as, “If the ship at the end of the transition is no longer the Ship of Theseus, at what point did it stop being the Ship of Theseus?”

If your head hurts, don’t feel too bad. It’s a paradox. There is no definitive answer. However, in trying to come up with one, philosophers dredge up all kinds of titillating ideas and explanations. Old cars, it turns out, introduce fascinating nuances to this age-old metaphysical quandary.

“The Ship of Theseus is one of many different puzzles that puts pressure on intuitive judgments about artifacts, starting with the idea that ordinary artifacts survive gradual change,” says Dr. Maegan Fairchild, assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan. “Cases of art restoration are already challenging enough, and interestingly, different issues arise when we start thinking about mass production. Classic cars are a tremendously rich intersection of these questions.”

Fairchild admits she is not a car enthusiast, but her study of metaphysics and aesthetics examines how some objects seem to deal with change successfully while others don’t. “In the Ship of Theseus, we’re negotiating how much of the ship we can change. You can take your car to the mechanic for new brakes and when you pick it up a few days later, it is still the same car. But imagine, instead, it was my grandfather’s truck that only he had ever repaired. I’d be quite reasonably furious if you had it fixed at a shop, by some other mechanic, without my permission. It’s a case where an ordinary object is more than just its physical parts.”

Cases in which a car is with its original owner speak to something similar. The moment a car is sold to a second owner, it loses that quality.

Questions of restoration or conservation can get even thornier. Often, the goal of such endeavors is to “protect an artifact from other changes—the rust, for example, that might spread to the rest of the car—that threaten to destroy it,” Fairchild says. “But with mass-produced objects, are we trying to restore their condition or their function?” What’s more important, how it looks or how it actually drives? And what does “original condition” mean? Is it the design? Parts? Materials? How it operates?

Ensuring a car persists with all of its original parts may, in some instances, doom it to never run again if the caretaker does not have the ability, knowledge, or tools to make it work reliably as designed. Certain pre-war cars and technologies come to mind. Is it more “original” in that state, or, if it runs and drives but uses, say, an electric starter instead of one activated by a vacuum switch?

Originality and restoration are concepts that depend on perspective, Fairchild argues. “Going back to my grandfather’s old truck, restoring it to the out-of-box condition would make it valuable to someone who cares generally about that model, but in the process you’d be destroying the thing that I personally care about. The stakeholders matter here—the car may be of interest as a historical artifact, sentimental object, art object, functional object, or even a financial investment.”

Nobody has explored these discussions from an automotive perspective in greater detail than car collector Miles Collier, founder of the Revs Institute and author of the fantastic book The Archaeological Automobile. On the subject of the Ship of Theseus, his mind immediately goes to a 1990 English court case concerning whether a 1929 Bentley race car known as Old Number One could truly claim that title, given all of its changes in the intervening years.

“The car had experienced so many modifications and evolutions in and out of period that there was a real question of whether the new buyer had the authentic item or a pile of parts from subsequent evolutions,” Collier explains. “The judge determined it would be hard to argue the car was Old Number One. But if there was anything that could be Old Number One, this was it.”

In Collier’s mind, it was the proper conclusion.

“Ultimately, the reality of material things in a material world is that everything vanishes and disappears,” says Collier. “The only thing that survives the ages is essential, called The Platonic Aspect—the design and its conception, in the case of a car. We have to accept that matter of any kind is always in a state of becoming, transitioning, into one thing or another.”

Following that thread, Collier has a particular view on restoration.

“All restoration is fictional. That doesn’t mean it’s bad, but when you’re doing it, be aware you’re introducing fictional artifact as the kind of methodology, materials, and choices. Even the very fact that you are a person of the 2020s dealing with a car from 1935 means your values, your perceptions of the world, are limited to the scope of this moment. If it’s an 8C Alfa, you know it’s worth $15 million or something, and that makes you want to be careful and meticulous. But in 1935 the 8C was simply a product that Alfa Romeo needed to go down the road and eventually make some money. The factory approach was to have great fit and finish on what the customer could see, but on what wasn’t visible… not so much. That kind of thing is extremely difficult to replicate in restoration.”

Collier’s view that all restoration is fictional has a parallel in philosophy. Mereological essentialism is the view that no object can survive any change in its component parts—that the moment a car drives off the production line and microscopic bits of rubber wear off the tires, it is no longer the same car.

“From that point of view,” Fairchild says, “the sense that there can be any continuous object in existence requires some kind of fiction-telling. In real life, mereological essentialism is usually plausible only in rarefied cases. What it does is get us a clean view of what is important to objects.” Think of, for example, driving gloves that Paul Newman wore; we understand that the leather may have cracked and aged, but we still treat them as the same pair of gloves. The story that we tell ourselves, the one that matters most to the object, is that this material was once on Newman’s hands.

Still, for Collier, the most intrinsically valuable and culturally significant cars are the super-rare “all-there” examples that survive unmodified from their original state. Unmodified but not unmarred; unlike Han Solo frozen in carbonite, cars are real-world material objects that suffer degradation even in the best of storage conditions. The value of such cars, in part, is their testament to the vehicle’s original configuration that serves both as a historical record and as an example to guide future restorations of similar cars.

“The important thing is to maintain the role of archaeology, which is to maintain the vehicle’s connection to both past and present. However, I’m sympathetic to wanting to make things more practical, usable, convenient. I would much rather have an old car that has had minor modifications but is usable, rather than a technically perfect thing that nobody drives so it goes into the junkyard.”

So what about the destroyed Ferrari? Is it still the same car?

“The 500 Mondial is evocative,” Collier says, “and [after the fact it will be] maybe not so different from cars with what I call anonymizing restorations—in which every element and indicator of the car’s idiosyncratic history make it an individual rather than the one that is one of a series of industrial objects.”

Some in the hobby assign special meaning or value to a factory restoration from, say, Aston Martin, Jaguar, Ferrari, Porsche, or Mercedes-Benz. However, Collier doesn’t correlate those services with any greater authenticity than he would another top-tier operation.

“A replica made with authentic parts on which every original material has been transformed, and in which everything fits perfectly and there is no sign of wear, has nothing to tell us about the car from the past. It can, however, have some value in terms of how that car in the past operated, particularly if the mechanical restoration was done with fidelity to the original systems.”

Despite what some owners and experts deem to be original, there are numerous “documented” cars out in the ether that are anything but. Kinney, the Hagerty Price Guide publisher, remembers one in particular:

“I know of a Ferrari that in the 1970s was wrecked—and I mean it basically fell off a cliff, so it was destroyed. I don’t think anyone who owned the repaired car since then has an idea there was ever damage. The point is that, at the time, it was never a particularly important car, so all of the work was done in an Italian body shop where pieces were either fabricated or parts were purchased from the factory. Now, it’s aged appropriately so nobody would ever come to the conclusion that this has happened.”

Like it or not, money is often a critical factor at this tier of the collector realm. Certain truths are not the sort owners want to go digging for, as any indication a car is not what it purports to be could come back to bite the owner upon resale. We should point out, however, that wholesale bodywork, in particular, makes no difference for some cars while it means everything for others:

“In the world of Cobras,” Kinney notes, “a re-body is a huge detriment to value because people want to protect the authenticity of the originals amid all of the replicas out there. But in other worlds a re-body is an improvement; you can buy body shells for a Mustang and it’s known as an acceptable substitute. The same is true for some British cars.”

In some ships, it seems, an entirely replaced hull is no big deal. However, the status that originality represents, Kinney wagers, can play an important role.

“There is an element of elitism that surrounds the car when an owner is able to declare it all-original. And then, be careful what you wish for: The cars that we covet now, almost all of them, at some point existed as used cars that weren’t worth very much and were treated as such. This is especially true of race cars.”

Race cars, especially those with notable competition history, tend to be worth a lot of money. Big money means big incentive to ensure a car’s survival, and even the most heinous damage, abuse, or modification may be washed over if the financial juice is judged worth the squeeze at the other end of the restoration.

“Look no further than Ferrari Classiche,” says Rudi Koniczek, a veteran high-end restorer with a particular expertise in Mercedes-Benz 300 SLs. “All they need is a chassis number. Fifties and Sixties race cars were trashed, wrecked, burnt to the ground, and generally clobbered. People died in them. However, if a car like that raced at Le Mans and there’s a fender left or chassis number, someone is gonna build a car around it.

“It’s not so different with Mercedes, either. I’ve fixed cars that had been completely wrapped around telephone poles or destroyed in house fires. Cars like that can go on to win shows.”

At this tier, the invisible rules that seem to govern what cars are deemed worthy, or valuable, can seem arbitrary and even alien. As an owner and a restorer, part of the process is navigating that labyrinth and deciding what rules you choose to follow, followed by what constitutes bending versus breaking them.

“Let’s take an alloy-bodied 300 SL, cars that were very fragile,” Koniczek says. “Many were re-skinned and rebodied. If a perfect, flawlessly restored alloy car is worth $7M, what about an original example that is so screwed up you wouldn’t drive it? That’s not an easy judgement.”

As a metaphysician and philosopher, difficult judgments come with Fairchild’s territory. A pretty good heuristic—a mental shortcut for solving similar problems of a type—for Ship of Theseus puzzles is tracing the history of a given object.

“If what is essential to an object is its causal history, the story that we tell about it concerns its path from creation to now,” she says. “Like a winning race car, or a car that belonged to an important celebrity, sometimes that history is what we care most about. Think about sourdough bread that uses the same starter—what matters is not the particular bits of the bread like the flour, but the continuity from the source. Often this is the best approach to apply to complicated objects that by their nature are going to incur a lot of causal change in their lifetime, because of wear and tear. Houses are another good example.”

If history isn’t of primary importance, maybe it’s how the object is used. For race cars competing in period, their chief focus was maximum performance. From that point of view, individual parts did not always matter. A team might swap engines, transmissions, or aerodynamic parts without a second thought; it follows that what is essential to that object is that it continues to be treated that way when it is used on the race track now. Whatever changes it experiences simply become new chapters in the story.

Jazz music, another discipline that cares deeply about what its creators and practitioners intend, offers an interesting parallel. “In many jazz pieces,” Fairchild says, “improvised sections are extremely important. But novelty with each performance is part of the experience—it would not be a proper rendition of the original if the music is repeated exactly from a previous performance.”

A different heuristic might be making sure the object has its essential parts—number plate, engine, transmission, et cetera. This is particularly difficult in cars, though. There are just so many parts, combined with the understanding that some—tires, oil, brakes—are by definition meant to wear, while others are meant to last much longer. Even still, two identical cars with identical parts may not be identical in their significance. The final air-cooled VW Beetle ever built is a lot more important than the twelfth-to-last.

There are no easy answers here, which is part of what makes these questions so interesting. As sold, the Ferrari 500 Mondial in question did not have its original 2.0-liter Lampredi-designed engine but rather a later, still-period-correct 3.0-liter engine. Does this matter? Apparently not to the buyer, and, as collector car analyst Rick Carey points out, it likely helps that Ferrari did sell 750 Monzas with this engine in the ’50s. After all, nobody expects that the car will be original when the entire thing will have to be rebuilt almost entirely from scratch.

What matters is that the car is understood to be what it professes to be. And on the other side of its restoration, the car’s right to call itself Ferrari 500 Mondial #0406MD will be examined, judged, and evaluated by many interested parties. It’s their perspectives that will carry the most weight.

Our guess? Given the dollars and reputations in play, the end product will go over a bit better than Monty Python’s distressed parrot owner looking for recompense:

SHOP OWNER: “Sorry gov, we’ve run out of parrots.”

CUSTOMER: “I see, I see, I get the picture.”

SHOP OWNER: “I’ve got a slug.”

CUSTOMER: (glares) “Does it talk?”

SHOP OWNER: (shrugs) “Not really, no.”

CUSTOMER: Well, it’s scarcely a replacement, then, is it?

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

This can be summed up much shorter and much more simply.

The buyer will buy the pile of parts here. It may have the plate still on it to ID it.

He will contact Pininfarina and have the pile shipped there. They will rehammer out the original metal and use ever bit that is salvageable. Surprisingly they will save most of what you see. Replacement parts will be formed in much the same ways the original body was built.

In the mean time a search will go out for the missing parts that still may exist. The Driveline and other parts will show up or reasonable exact examples will fe found and used.

Not to mention that Ferrari may actually have some NOS parts in stock as many of these sports car companies will have parts around that may shock you. Porsche in the 80’s had enough parts to build a 917-30.

When it comes to restoring a car like this it is not like a Camaro or Mustang where you just order parts from a Catalog to restore it. They will spend the money to restore it like you would restore the Mona Lisa. The old style ways to reproduce or restore parts will be used and in the end it will get a blessing from Ferrari as being the original car.

Also the fact most race cars are far from original buy the time they finish racing. Still today many debate how much of the Foyt 77 Winner is still the original car. Some are lucky and get parked but most continue to race crash and get rebuilt. The one Foyt car in the Museum is all original as it never raced again. That is rare.

So the philosophy is much different than a regular restoration. Levels of original and standards of original are different. A body and formed in the same shop in Italy is not like a Mustang Fender from China.

This is not a project for the poor or the weak. It take time and a lot of money and the right people globally.

Since so few of these cars exist it opens the door for more open acceptance.

“Not to mention that Ferrari may actually have some NOS parts in stock as many of these sports car companies will have parts around that may shock you. Porsche in the 80’s had enough parts to build a 917-30.” — and if that were the case with this Ferrari, would it still be the same car, blessing or not?

As for Ferrari. If you let them restore this from what is left they would call it original. They do offer the service. Everything has its price.

As Chuck once said my AC Delco parts don’t just fit they match.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O86lwPAS6xA

There is no formula for how much original car is left as long as there is something left.

As to how it is was restored and who did it matters.

It would be the same car, if it is in conformity to its original specs of that vin number car . If period parts are sourced from period vendors. The work being performed by Ferrari to see that it is done as the composers intended is also big. It’s just a car , it’s not a Picasso .

Thank you! Great points and nice response. I am glad to see these restoration articles for my father gifted me his 1980 Fiat Spider in 2019 it now has 244 thousand plus on the clock with no rebuild of the engine. Original Car except for one respray and he reupholstered the front seats so thanks again for your perspective.

Brings to mind the old “joke”;

George Washington’s axe for sale. Handle replaced twice and the axe head once.

This is a well known example, and came up in my discussion with Dr. Fairchild but ultimately did not make the article.

Sometimes referred to as “my grandfather’s axe.”

This was an excellent and thought provoking dissertation. Once one wraps one’s head around some of these issues and attempts to adopt some conclusions, more challenges exist. In the fields of racing and other endeavors wherein, as an above commenter noted, artifacts change and evolve, multiple iterations of a possible return-to-the-past restoration will present themselves. Porsche 935 009 030, itself constructed with some components from another crashed 935, placed second overall and first in class at Le Mans in 1979, and has been restored to that point in time. This car also won the 1981 24 Hours of Daytona overall. Yet that car was also converted into a sort of-934 and raced to overall victory at Sebring in 1983, becoming the only GTO class car to ever win Sebring overall, arguably the most historic impact of this car’s lifespan. Which iteration of these events, and others, is “true”? As stated in the article, the restoring owner and his currency have the decisive vote, and will get to pick the historical moment in time to which the artifact is returned by restoration. Until the next owner, who may or may not honor that particular point in time. The conundrum of Theseus isn’t just a ship or a car or a tangible thing, it is also a calendar, and a clock.

Well said!

My wife and I had a conversation just this morning on a related topic. She had seen a picture of someone “and it didn’t even look like her”. Turns out, the picture had been filtered, altered, photoshopped, whatever can be done to a photo nowadays. My argument was that it “wasn’t really a picture of her”. To me, to be a picture of her, it had to actually be “of her” and not of all the digital rearranging that’d been done. I finally conceded that it was a “representation” of her, but it still wasn’t “her”. But then I got to thinking – what if that lady had actually had plastic surgery, botox, whatever can be done to a face nowadays. Would it still be “her”? Hmmm. I supposed it would.

There are times when I would like to not have to consider conundrums like these. There are times when I’d rather just kick back with a nice bourbon, a few snack crackers, and a good action flick on the TV.

Well written , well said DUB6! A person could split hairs all day long and there wouldn’t be a consensus amongst the ranks. Opinions and beliefs are carbon fiber strong and changing those human characteristics isn’t easy or always possible.

” Philosophy is the talk on a cereal box. Religion is the smile on a dog” – Are you talking about this cars intrinsic value or its intrinsic value? Are you making the case that because of its history those small remnants of it that remain represent somehow an immutable core ? As though it has a soul (for lack of a better term and the exact definition of which I’ve yet to find ) that lives on? All things are transitory.- “I know what I know if you know what I mean.” Time to let this thing go.

Oh, come on. Let’s cut through all this metaphysical mumbo-jumbo and cut to the chase. Somebody paid ridonkulous moolah for this mangled pile of Ferrari metal…because they expect, correctly or not, to make a riddonkulous pile of moolah in return. Nothing more, nothing less. This ain’t that hard to figure out, folks.

Reductive, in my opinion, but fundamentally not wrong!

Another philosophical angle… before you choke me in the shallow water…

This is a lot like baseball cards or even currency. What gives it value is that two people agree that it has value. Now cars are a little different because they have some intrinsic value just for being a functioning car (which I imagine that this will become someday) but when you get into these high end cars, that value pretty much gets lost in the rounding… so we are back to baseball cards. All this person needs is one other person who thinks this car has value and all of the other factors just don’t matter. I do think that this is the rabbit hole you end up going down when folks put ‘provenance’ and VIN tags over the intrinsic value of cars though

More Bourbon and snack crackers, please! Put on a Bond movie, please!

Here, here! My head hurts.

A car should have more than 50% of its original parts to be considered the original car. If the car has 80% replacement parts it is not the same car and shouldn’t be presented as such.

TG – I won’t shove you in the shallow water but I might call the lifeguard, although I just got comfortable in this chair. I’m definitely babbling somewhat in the grey area of semantics but it does seem relevant. Since this Ferrari came to auction there seems to be a split between two camps. Those who see it’s intrinsic value ( the value of what it simply is on it’s own frequently ‘ a piece of twisted junk ) and those who argue that its intrinsic value is financial ( 1.8 + and potentially more in the market after ). But there doesn’t seem to be a general consensus does there? So if we look at that baseball card ,and get back to Thesues in a way , what if that baseball card worth has been ripped in half? ‘John+ D’ suggested a benchmark of 50% and while I would think that 51% would be preferable being something of an accepted standard ,in this case it is rather arbitrary. Is half a Johnny Bench worth half of a complete card? So it is with this Ferrari. While you can imagine it going through a complete painstaking restoration and being brought into the rare air of ‘that’ sector to be auctioned, you can also imagine a purist with a stable from Maranello waving it off as being ‘interesting but not authentic enough’. And it’s not a bad point. From a very human perspective if you’re lucky enough to find yourself in the seat of a car that Fangio drove you can, and probably will, think that your hands are on the same wheel as when he drove it. If instead its a recreation, as faithful as it may be, that connection is lost. – Sorry 6 , I’m out of bourbon and crackers and I haven’t got any Bond films. But I do have a nice single malt scotch and a copy of ‘Un Homme et Une Femme’ with that great footage of the GT-40. You do speak French right?

Interestingly enough… this half of a Honus Wagner baseball card went for around half the going rate for a whole one, so I guess there is some prorating even in the baseball card world

https://catalog.scpauctions.com/1909_11_T206_HONUS_WAGNER___PSA_AUTHENTIC___THE_HO-LOT50061.aspx

With that title, I’m not sure one needs to understand the language.

Instead of Theseus let’s say “Tally Ho”.

Episode 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FhTu3aGM60

And six years later: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uuh_T648J_8

You’ll need a lot of beverages.

Correct your links and removed your second comment for clarity’s sake. Interesting watch!

Thanks!

Grr… wrong link. Sorry! Try this one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FhTu3aGM60

six years later should be accurate.

This is a fantastic piece of automotive journalism! I enjoyed reading it (and pondering its implications) immensely.

I was intrigued by the concept of mereological essentialism (that objects are always changing through use and wear, and never truly “original” in a literal sense). I believe this is how individual cars develop their unique personalities over time: every example wears a little differently, and is kept running by its owner through unique decisions about when and how to maintain and repair them. Over years, these small personal choices impart on the car a unique feel; this is also probably one reason for the sentimental attachment we may feel towards a particular car (or, in Dr Fairchild’s example, her grandfather’s truck).

Please write more pieces like this!

Thanks, Edward!

As Monty Python would say, “It’s only a flesh wound!”

In the final analysis it’s a question of what is legal. Legality goes to documentation, pieces of paper, that constitute the bridge between the past and present. Jaguar for example has produced “continuation” E-types and XKSS’s, assigning them with hitherto unused VINs. They are faithful, high dollar recreations of the original road going cars, if anything with far superior fit, finish and mechanical blueprinting, but they cannot be registered to be driven on public roads because they lack that all important bridge to the past. They didn’t legally exist until now, and from a legal standpoint they are new cars that don’t meet standards established under modern automotive legislation. A Ferrari with this VIN did exist in 1954 and an esoteric collection of its original atoms remains, more importantly with legal documentation to establish its continued existence and current ownership. It is grandfathered. It is what makes it “real”, the degree to which is in the eye of the beholder.