Kick-Start Collection

James Hewitt, an information analyst with Hagerty, started riding dirt bikes with his father as a child. He bought his first motorcycle at 16, sold it for a profit, and has since bought, ridden, and sold more than 100 bikes.

When we talk about the collector car market, we tend to forget that a big chunk of it isn’t cars at all. There are 2.9 million registered collector motorcycles on the road today, 9 percent of the overall collector vehicle market. Some 35 percent of motorcycles are registered as classics—three times the percentage of cars designated as such.

Yet a number of car collectors know relatively little when it comes to motorcycles—or worse, they assume their car knowledge carries over, and many times, it doesn’t. Consider this your primer.

Smaller, more affordable

Whether for nostalgia or for fun, people have been collecting motorcycles since long before World War II. The market for them matured in the same manner as that for cars, picking up through the ’70s, booming and then collapsing in the ’80s, and growing steadily in the 21st century. Also like cars, the collectibility of motorcycles is often led by people buying what they rode or wished they rode in their youth. Somer Hooker, former motorcycle dealer and current broker and consultant, cites pictures of people in the ’30s with turn-of-the-century motorcycles as evidence that “the 25-year rule has always been the axiom” for motorcycles.

Collectible motorcycles differ from cars in significant ways, however. First—and perhaps most important—they are, comparatively speaking, quite affordable. Combined, the 15 most expensive motorcycles ever sold at auction are worth less than a quarter of the value of the most expensive car.

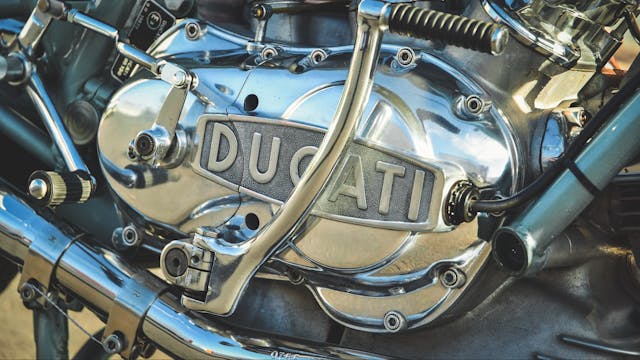

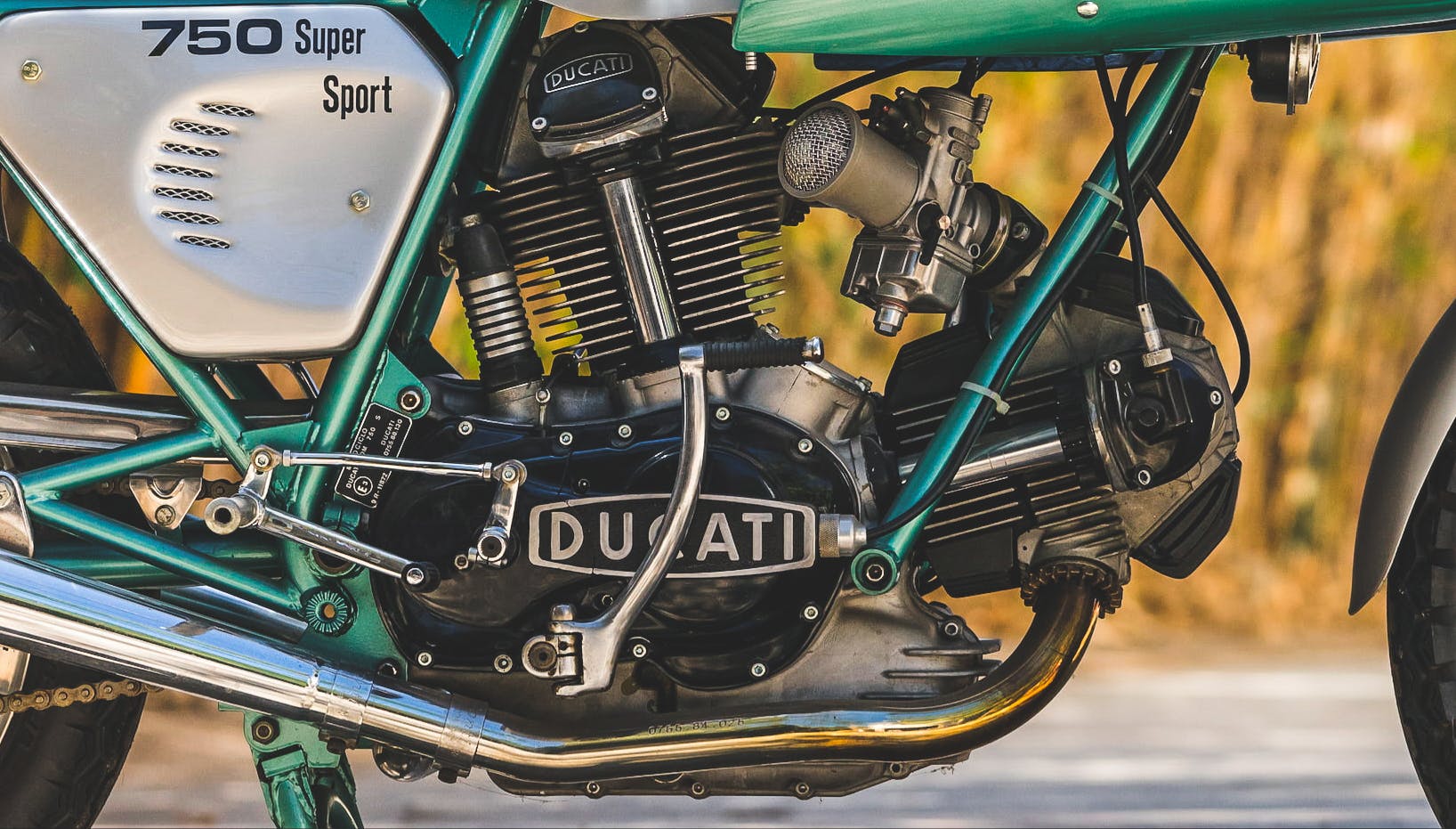

A Ducati 750SS—the two-wheeled equivalent of a Ferrari 250 GT SWB—can be had for $100,000. A real Imola racer—the equivalent of a Ferrari that raced and won Le Mans—might clock in at $700,000–$1M. Adrenaline junkies have long known that bikes offer an affordable way to go really fast. The same holds true if what you’re after is history: You get far more per dollar with motorcycles.

The lower end of the classic motorcycle market, meanwhile, is driven by people looking for cheap transportation. It’s not uncommon for buyers to choose ’70s Japanese bikes as their first motorcycles. (That’s how I got here: My first rides, purchased in high school, were a 1969 Honda CL350 and a 1972 CB350.) Collector interest in these has boomed in the last five years, yet a CB350—reliable and usable like a ’90s Civic but oh so much cooler—can still be had for just $1500.

Motorcycles are also small, an obvious fact that drives very different kinds of collecting than cars do. Motorcycles can be hidden away and forgotten about, like the 1916 Traub that was found hidden under the porch of a home in Chicago. A collector can sell one car, buy one motorcycle, and gain garage space in the process.

Many owners who have an old bike in their garage have only a faint notion of what it’s worth, and most assume the answer is “not much.”

This combination—small and cheap—leads to many owners holding on to motorcycles they don’t particularly care about. While hunting for deals across the Midwest, I have seen everything from a barn with 100-plus motorcycles stacked on top of each other to a motorcycle that was ridden for three years then tucked away in a corner for 30.

Many owners who have an old bike in their garage have only a faint notion of what it’s worth, and most assume the answer is “not much.”

In most cases, their assumption is correct: 60 percent of motorcycles in the Hagerty Motorcycle Price Guide have a #3 value of less than $5000. Yet because the dollar amounts are small, it’s all too easy to get ripped off or, conversely, get a good deal. Say you buy a $3000 bike for $1500. Not a huge amount of money in absolute terms—perhaps an insignificant amount to the person who wants to clear the rusting, greasy hunk of metal from their garage—but the percentage difference is the same as buying a $40,000 Mustang for $20,000. Then buy 10 of these bikes. Congratulations, you just started a collection that essentially appreciated 50 percent the second you bought it. Meanwhile, everyone else is excited about their cars appreciating 10 percent.

What’s hot, what’s not

The motorcycle market is not merely a cheaper, smaller version of the classic car market, where you buy 10 times the volume. Buyers here behave differently.

For one thing, this market is more stable. The lower value of motorcycles means that huge swings are less prevalent. “In a down market, people will always have money for a cheap bike or a beer and a burger,” notes Nick Smith, former motorcycle auction manager and current CEO of dealer Classic Avenue. Values for top-of-the market bikes—those that cost $150,000 or more—are as volatile as the $1M-plus car market, Smith says, but because there are fewer motorcycles in that price bracket (50 percent more cars have an average #2 value greater than $1M versus motorcycles with a value greater than $150,000) the overall effect on the market is limited.

Another key difference: When we talk about a top-dollar motorcycle, we are typically referring to something built before World War II. That hasn’t been true in the car market for some time. Eighteen of the top 20 motorcycle sales at auction are prewar, whereas 18 of the top 20 car sales at auction are postwar.

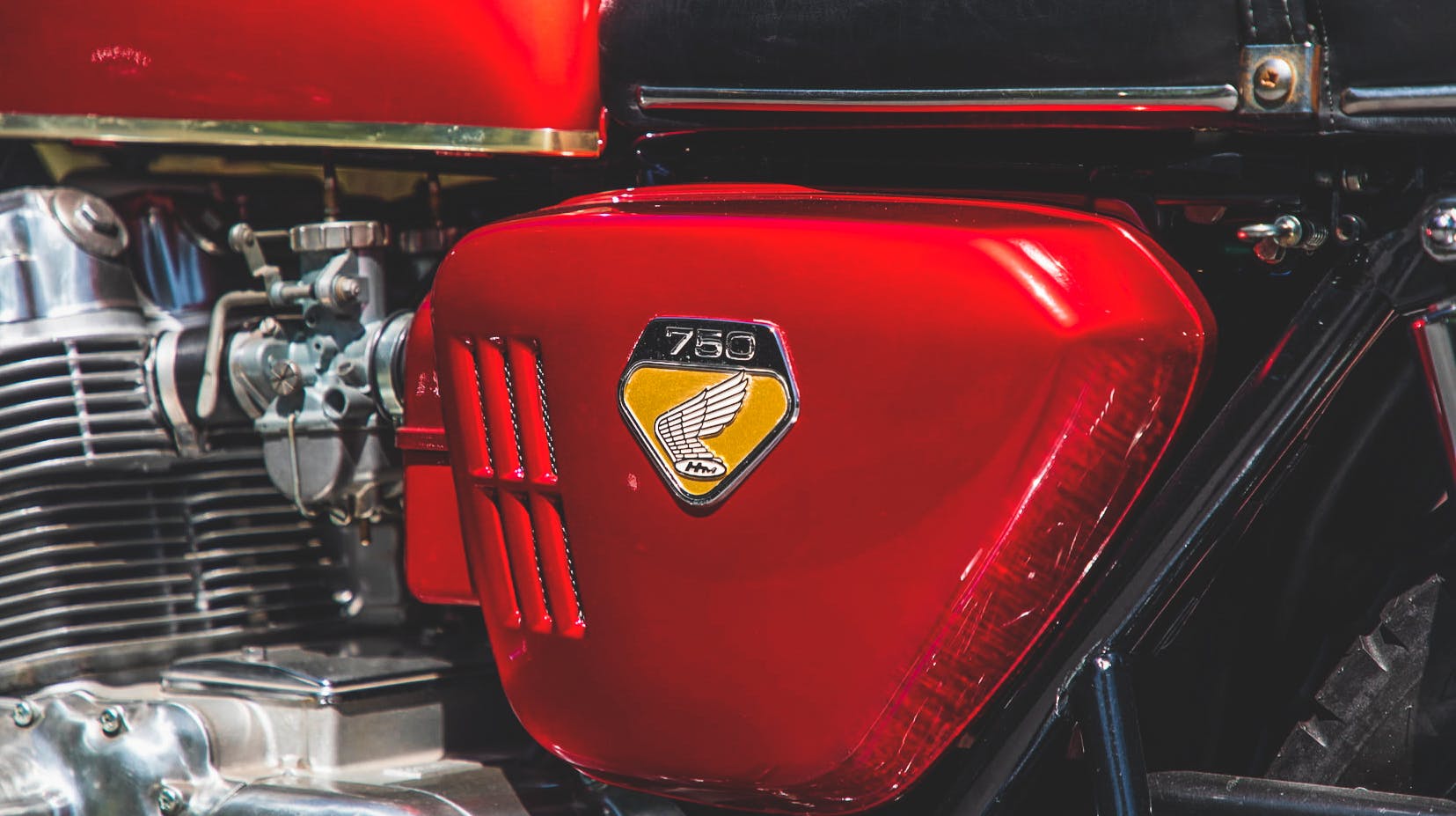

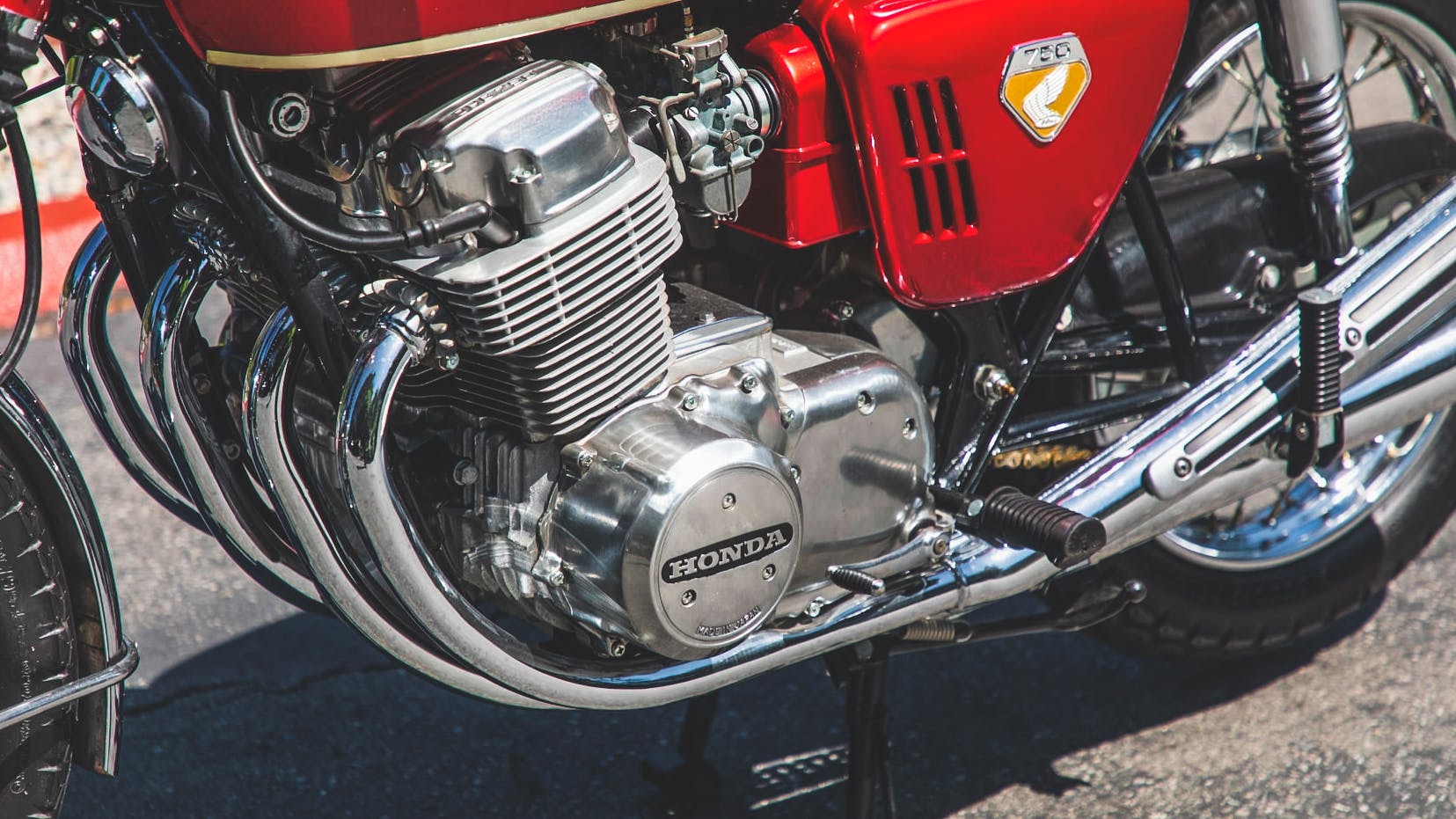

That said, 1970s-and-newer bikes are gaining steam. “The big trend now is toward usable [bikes], says Somer Hooker. “People want to experience them.” Group rallies are becoming popular, which helps explain why we have seen a large surge in Japanese motorcycles that can reliably run at speed for hours. For example, Honda CB750 values doubled in the last five years as older buyers moved on from kick-start British motorcycles to their smooth, electric-start Japanese counterparts.

Honda CB750 values doubled in the last five years as older buyers moved on from kickstart British motorcycles to their smooth, electric-start Japanese counterparts.

The increasing popularity of usable bikes also points to the fact that classic motorcycles are overwhelmingly bought for pleasure. Attend a few motorcycle auctions and you’ll doubtless hear anecdotes about car collectors swooping in and picking up bikes either as garage art or a speculative investment. Hagerty data says that’s still the exception. Only 5 percent of large car collections insured with us (five or more cars) have a motorcycle, and 45 percent of motorcycle policies do not have a single collector car insured. The speculative money that has flowed into the collector car market over the decades has mostly skipped over motorcycles. People buy old bikes to ride them.

What to look for, what to avoid

The best motorcycle to buy is the one you think looks the prettiest or pulls at your heartstrings. If that’s a 1986 Yamaha Virago, then that’s the right investment. Still, there are a few practical things to look out for. Many carry over from cars: correct parts, matching numbers (note that many engines and frames won’t actually match from the factory but will be within an accepted range), and quality of restoration/preservation.

1. Originality. Motorcycles are often treated rough, ridden hard, and put away wet. Fewer bikes than cars survive in nice original condition.

2. 2000 miles is a lot. Motorcycles generally don’t get ridden as far or as frequently as cars do, which means that many of them have low miles. But per the above point, those miles could have been very hard ones. Rule of thumb: Divide a car’s mileage by 10 to get the equivalent motorcycle mileage (e.g., a 500-mile motorcycle is valued like a 5000-mile car).

3. Paint isn’t difficult to fix; chrome is. Re-chroming is expensive, and surface rust on chrome is usually the area where old motorcycles start to show age first. Don’t be deterred too quickly, though. Rub water and aluminum foil on the chrome to see if it will clean up. Sometimes it does, but if it doesn’t, prepare to spend a considerable amount to fix it.

4. “Just needs a tuneup.” This means it needs more than a tuneup, but don’t let that scare you—these are simple machines, after all.

5. Buy it for the fun, not for the deal. A $1000 CB350 that you can restore for around $1500 can give you more joy and pride than a $2500 restored one. Just make sure you’re going to finish the project; many don’t (indeed, a large number of the long-stored bikes I encounter are stalled restorations).

6. Details matter. It’s easy to do an amateur garage restoration on a motorcycle with spray paint and polish. Professional work makes all the difference.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.