Parted Out? The future of car components in an EV world

This is the latest in a series of Hagerty Insider articles on the future of classic cars in an electrified world. Catch up with an examination of the impact of internal-combustion engine bans in Europe or an exploration of what regulations might come into effect in the United States. This is a more granular approach: What is the future of the myriad parts that keep gas engines going?

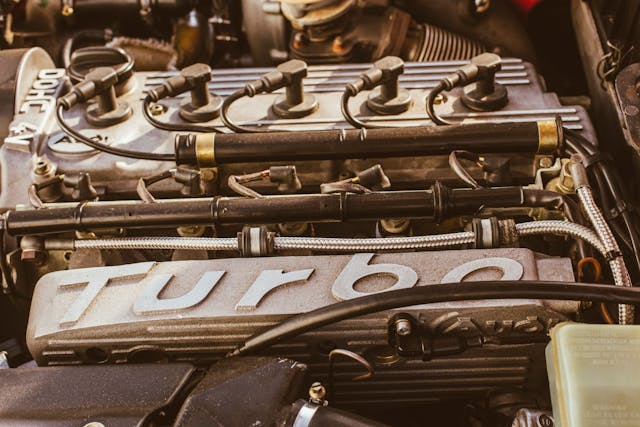

Barely a month goes by that some automaker doesn’t announce that their future lies in electric vehicles. Last week, Renault said that more than 90 percent of its production would be electric by 2030, joining a growing list of auto brands that have committed to abandoning fuel burners for full electrification before the decade is out. Auto suppliers, the companies that produce the belts and hoses and water pumps and spark plugs that make engines run, are furrowing their collective brows, wondering whether there is a future for an industry that has been around for more than a century. As a car enthusiast, it’s hard not to feel like a dinosaur as it watched the meteor blaze across the sky.

“Just in the last two months, the phone calls I’ve been getting have really heated up,” said Mike Spagnola, vice president of OEM and product development programs for the Specialty Equipment Market Association (SEMA), the industry trade group for makers of aftermarket components which includes classic vehicle parts suppliers. “I like to work on gasoline vehicles, but you can’t ignore the fact that this is coming.”

Well, what is coming, exactly? We know that some luxury brands like Cadillac and Jaguar have said that they are building their last gasoline powered vehicles. Cadillac says that it will not replace any of its internal-combustion engines as they go out of production and the brand expects to be fully electric by 2030. The world’s largest automaker, Volkswagen, which despite the pandemic built more than 25,400 vehicles every day of 2020, is shoveling $33 billion into a massive electrification effort. All work on internal-combustion engines at VW will stop in 2026, the company says, and it promises to make its entire supply chain completely carbon neutral in the process. VW is so big that the company figures that it alone is responsible for 1 percent of global carbon-dioxide emissions.

However, we also know that there are 278 million vehicles registered in the United States as of 2019, of which a mere 1.5 million are electric and another 3 million are hybrid. In 2020, pure electrics represented only 2 percent of the 14.5 million light-vehicle sales that year. SEMA figures that in any year, between 12.5 million and 13.5 million older vehicles get scrapped, meaning it would take more than 20 years to turn over the entire U.S. fleet of fuel-burning vehicles—and that’s assuming we went to 100 percent electric tomorrow and the scrappage rates remained constant, which they aren’t.

In fact, scrappage rates are going down as cars last longer and new cars get more expensive, making it worth it for owners to repair their older vehicles. As of February 2021, the average new car price was $41,066, a substantial layout in a nation where, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median income in 2019 was $68,703 and the average income was much lower.

So, a flood of new electric vehicles—130 models spread across 43 brands by 2026, according to one study—are landing in a market in which a tiny percentage of sales are currently electric and in which most people, when they buy, go for pickups and crossover SUVs. “If we reach 20 percent [electric] by 2025, that would be aggressive,” says Brian Daugherty, chief technology officer for the Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association (MEMA), an industry trade group for auto suppliers. “I personally think it will be lower.”

Unsold electric cars may pile up on dealership lots. Auto manufacturers may appeal to government for help (it certainly wouldn’t be the first time). Massive price subsidies, along with an expected drop in battery costs and increase in battery recycling, could make electrics more affordable, but the public recharging infrastructure still lags. Some states struggle even to keep the power on during heat waves and snowstorms. Only one thing is certain: Nobody seems certain what will happen over the next decade.

The implication for owners of classic vehicles seems less murky, as it’s likely that little will change for them so long as gas stations don’t disappear (a revolution that nobody expects for at least several decades). While original-equipment parts suppliers are contemplating a future without engines, suppliers of parts to classic vehicles, a $900 million annual market, according to SEMA, will go on.

“Bigger suppliers are switching their R&D dollars,” says MEMA’s Daugherty, “but as long as someone can make a profit making a part, they will do it. Rubber belts, spark plugs, hoses—those are fairly easy to make. Where you may see a problem is in parts that are less common.”

Suppliers may consolidate their product lines for engines, cutting the number of clutch types or spark plug part numbers they make, leaving some older vehicles out in the cold. This will come as no shock to owners of obscure classics, who have long struggled to obtain parts, but those who drive more common vehicles may, too, be left without adequate parts support.

The good news, says industry analyst Charlie Vogelheim, is that new technology such as 3-D printing will make obtaining some parts easier. “With 3-D printing you can bypass some of the past barriers to getting parts made, like tooling costs for molds and needing to buy a huge number to make it work out financially.” Adds Vogelheim: more entrepreneurs like Corky Coker of Coker Tire will come along and “create profitable industries around keeping old cars on the road.”

But current 3-D printing technology has its limits. It can’t make a cylinder head or high-stress suspension components like tie-rod ends. At least, not yet. Even so, figures SEMA’s Spagnola, any serious shortage of engine parts would be “years and years and years away. Superchargers and air intakes will be made for many years to come.”

Which may be little comfort to the owner of a 1965 Mustang—already a 56-year-old car—who is planning to pass the car on to his or her children as a family heirloom. Timelines are long in the classic car world. Will a 1965 Mustang still be drivable in another 56 years?

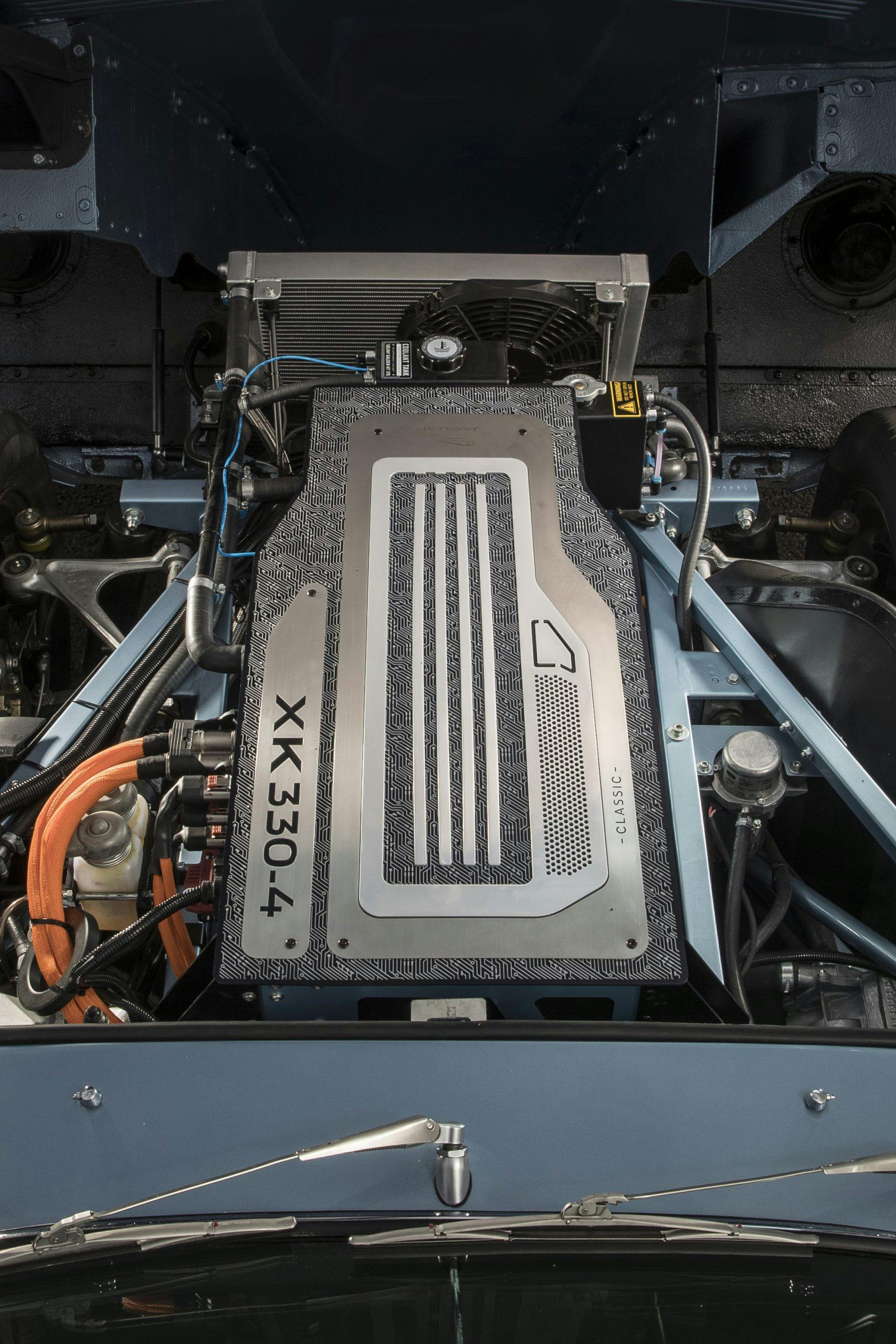

Well, there is always electric conversion.

As with new electric vehicles, electric conversion of classics is in its infancy, but it is growing. The annual SEMA show in Las Vegas in November is where makers of aftermarket, restoration, and hot-rod components come to show off their latest products. Joining them in 2021 will be an increasing number of electric-conversion suppliers, and sprinkled through the halls will be a significant number of all-electric show cars. For the first time, the show will have its own section for electrics, and “dozens of people have contacted me about it,” says SEMA’s Spagnola.

“You can’t deny the power,” says Spagnola, who recently rode in a 1000-horsepower electric prototype from Faraday Future, a Chinese-owned electric start-up. Currently, the quickest-accelerating production car on the planet is the 1020-hp Tesla Model S Plaid, which can hit 60 mph in just over 2 seconds straight off the showroom floor.

Going fast never goes out of style, especially at SEMA, where independent companies like AEM Electronics, a well-known supplier of dash displays that is now building electric-motor controllers for EV conversions, will share the electric spotlight with major automakers like General Motors. Last year, GM showed off a 1977 Chevy K5 Blazer with what it called a pre-production version of an electric crate motor that will be sold through Chevrolet Performance. The original 400-cubic-inch small-block V-8 was replaced by a 200-hp electric motor from the production Chevy Bolt mated to a four-speed automatic. Total range: 238 miles. While the power may not sound like much, its more than the original engine (175 horsepower) and it comes with the instant torque delivery of an electric. More powerful versions of GM’s eCrate package are surely on the way.

The blazing meteor seems to promise both radical, violent change as well as huge promise for the automobile as we know it. The dinosaurs may not survive, but new creatures will flourish that are likely to be just as interesting. In the end, notes the analyst Vogelheim, electrification may force the classic-car community to divide into those who want to preserve old cars as they are and those who just want to drive them, regardless of the power source.

“Is it about authenticity or mobility?” he asks. Each classic car owner will have to decide where he or she lands on that question, but it seems likely that, at least for the foreseeable future, the roads will be big enough for both.