Did This Progressive-Era Couple Invent Car Collecting?

When did “the hobby” of car collecting really start?

There’s a famous quote, attributed to Henry Ford: “Auto racing began five minutes after the second car was built.” Can we say the same of auto collecting? Did it start as soon as someone bought their second car?

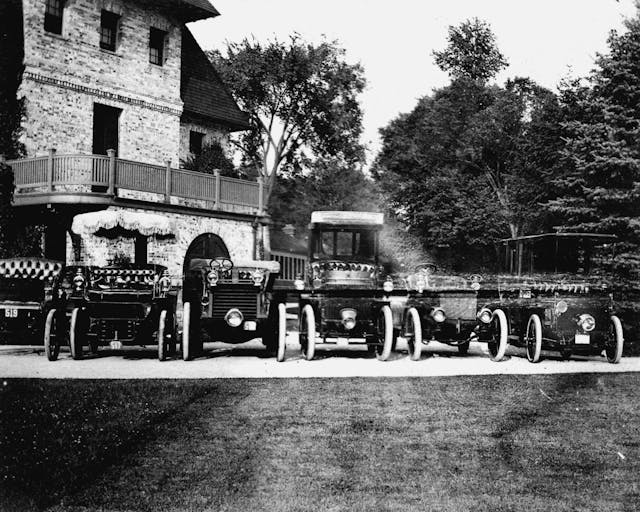

Probably not, and the Ford quote isn’t literally true, either. But the concept and ethos of car collecting, which grew in the 1930s and 1940s, goes back a lot further than many realize. By 1918, when the Western Front was still noisy and long before most popular “classic” cars had even been conceived, an East Coast couple named Larz and Isabel Anderson had already assembled a group of nearly a dozen motorcars. The Andersons kept acquiring cars well into the 1930s, carefully selecting for different styles and purposes, consistently maintaining them, and treating the vehicles almost like the children they never had.

Nobody would have called it a “car collection” then, but the Andersons’ approach to buying, enjoying, and preserving their automobiles is familiar to any 21st-century collector. And the cars are still around today, billed as America’s oldest car collection. It isn’t just their age that’s impressive, either; while not a huge group, the Andersons’ is a curated one that represents nearly every type of period drivetrain configuration and body style. Many of the vehicles were among the most expensive of their type when new. Most importantly, they are all completely original, have never changed hands, and still reside in their original garage, now known as the Larz Anderson Auto Museum. It may be America’s oldest car collection, but no other group of cars in the world is quite like the Andersons’, and 100 years ago it was way ahead of its time.

The Andersons

Larz Kilgour Anderson was born in 1866 in Paris, then raised in Cincinnati. He had the bluest of blue blood. His great grandfather witnessed the Boston Tea Party, was a captain in the Continental Army, and married William Clark’s (of Lewis and Clark) sister. His father was wounded three times in the Civil War and was a good friend and classmate of Robert Todd Lincoln, son of the president. After Larz dropped out of Harvard Law School in 1891, it was through that connection that he snagged a job at the American Legation in London. So began a diplomatic career, and after three years in London he was appointed first secretary of the American embassy in Rome. While in the Italian capital he met 18-year-old Isabel Weld Perkins while she was on her Grand Tour. A flurry of love letters followed, he proposed in Boston later that year, and the couple were married in June 1897. It was a “simply planned and admirably executed wedding,” according to The Boston Globe. Larz and Isabel rode away from the wedding in a horse-drawn carriage. A year later they became enchanted by the horseless carriage.

Although the couple’s collection and museum are now named after Larz, Isabel was arguably the more interesting of the pair. She was certainly wealthier. Born in 1876 to a New England family that traced its Massachusetts roots to the 1630s, she inherited part of her grandfather’s shipping and railroad fortune in 1881, when she was just five years old. Sources vary on the size of the fortune that went to Isabel, but it was well into the millions, and she was groomed for a life in high society in Boston and Newport.

Their Life and Home(s)

After getting married, the Andersons traveled. Together, they went on more than 70 trips to over 50 countries, colonies, and territories, and wherever they went, they acquired art and décor for their homes. They were voracious but also careful and deliberate, an approach they took when acquiring motorcars as well.

Larz’s diplomatic career peaked in the early 1910s. In late 1911, he became the United States Minister to Belgium and, after a year, Ambassador to Japan. The Andersons loved Japan, but after William Howard Taft lost the 1912 presidential election to Woodrow Wilson, Larz resigned and left just a few months after arriving. The Andersons then spent much of the rest of their marriage traveling, collecting, entertaining, and improving their properties.

Isabel, meanwhile, was never idle. Aside from high society life, philanthropy, and traveling the world, she supported progressive causes like prison reform and higher education for women. During World War I, she volunteered as a nurse with the American Red Cross and spent nearly a year near the Western Front. Isabel was also the first woman in Massachusetts to receive her driver’s license.

She was a prolific writer, too, publishing some five dozen works of poetry, nonfiction, short stories, children’s literature, musical theater, and travelogues. In some of her travel books, she devotes entire chapters to motoring, like 1915’s The Spell of Belgium (“Brussels is ideally located for the motorist”) or 1914’s The Spell of Japan (“Motoring is just beginning to be popular in Japan … Only in a city like Tokyo or Yokohama is it worth while for the resident to have a car the year round”).

When they weren’t abroad, the Andersons split time between three East Coast properties. One in New Hampshire was a getaway from society life. Their mansion on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, DC, meanwhile, was almost entirely for society life and one of the most fashionable addresses on the DC social circuit. Prominent guests included the Vanderbilts, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., John J. Pershing, and Douglas MacArthur, plus a slew of royals and nobles from abroad, including King Prajadhipok and Queen Rambhai Barni of Siam as well as Prince Andrew and Princess Alice of Greece, whose son would go on to marry Queen Elizabeth II.

For summers, there was a second foothold in New England. Weld, a sprawling family estate Isabel acquired in the 1890s, was located in wealthy Boston-adjacent Brookline, Massachusetts. The Andersons had it transformed into something palatial. The main residence, a 25-room mansion at the top of a hill overlooking the city of Boston, more than doubled in size under their tenure and housed various art and artifacts collected on their travels. A glorious Italian garden designed by famous architect Charles A. Platt sat adjacent to the mansion, as did a smaller but equally impressive Japanese garden, cared for by a full-time gardener from Japan. The Andersons’ penchant for collecting extended beyond art and automobiles, as Weld housed one of the largest groups of bonsai trees in the United States.

According to the biography Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age, between 1900 and 1940 an estimated 200 people lived and/or worked at Weld. The annual budget for the Brookline estate averaged over $200,000 (not adjusted for inflation). In addition to gardens and housekeepers, the Andersons also had a stable of horses, carriages, and cars to look after.

Their Cars, 1899–1918

Almost as impressive as the Andersons’ mansion was their buff brick two-story carriage house on the grounds of Weld. Modeled after the Château de Chaumont-sur-Loire in France, it was built in 1888. This was well before any widespread adoption of the motorcar, so at first the building housed dozens of carriages as well as horses in its handsome wood interior, separating them by elaborate stalls divided by marble panels and labeled with gold-lettered nameplates. The Andersons never stopped keeping horses and never got rid of their carriages, but by the turn of the century they were already enthusiastic early adopters of the automobile. They bought one nearly every year, gave it a name and a motto, kept it maintained by chauffeurs and mechanics, then retired it once it became obsolete. They rarely, however, got rid of anything.

The motoring bug first bit the Andersons in 1898, while they were in Paris. At the time, France led the world in automotive production and use, and these American aristocrats were captivated by the horseless carriages buzzing around the capital city. Motorcars were still very much luxury goods for the wealthy, but Larz and Isabel could very much afford one, and ordered their first car from Cleveland’s Winton Motor Carriage Company as soon as they returned to the States. The Andersons were among Winton’s first customers, and the car was a true horseless carriage with a sparse phaeton body, tiller steering, and simple single-cylinder engine. Since the Winton was their first car, they nicknamed it “Pioneer” and gave it the motto “It Will Go.”

Larz and Isabel ordered their second car in France in 1900 from a company called Rochet-Schneider. Largely a copy of a Benz design with a big single-cylinder engine driven by a leather belt, it also had a strange (and distracting) “vis-à-vis” seating arrangement, in which the passengers rode on the front seat and could either face toward or away from the driver. Theirs didn’t just come with funky seats; Rochet-Schneider provided a chauffeur who moved back to Brookline with the Andersons and lived with them for several years.

Like with many early automobile owners, speed quickly seduced Larz. By his third car, in 1901, he was already racing. The Winton Bullet, which the Andersons nicknamed “Buckeye,” is a 40-hp, two-cylinder racer. Four were built, and another became famous when Alexander Winton raced it against Henry Ford’s “Sweepstakes” car in 1901. Although Winton seized an early lead, the car broke and Henry Ford then used the prize money to start the Henry Ford Company.

With three properties to go between, the Andersons also wanted a car for longer-distance trips, and for this purpose they acquired their first and only steam car. Although the Stanley Motor Carriage Company built steamers in nearby Newton, MA, the Andersons went back to the French in 1903 for something larger, heavier duty, more complex, and much more expensive. Their Gardner-Serpollet had a four-cylinder engine when other steam cars had two, and the company’s patented flash boiler allowed it to come to steam in about 90 seconds, when other steam cars could take about half an hour. It also came with both summer and winter bodywork.

By their fourth car, a 1905 Electromobile from England, the Andersons had every type of propulsion—gas, steam, and electric—in their possession. The Electromobile, nicknamed “Bringer of Happiness” and given the motto “It Goes Without Saying,” was a typical early electric, and similar cars were popular in American cities by this time.

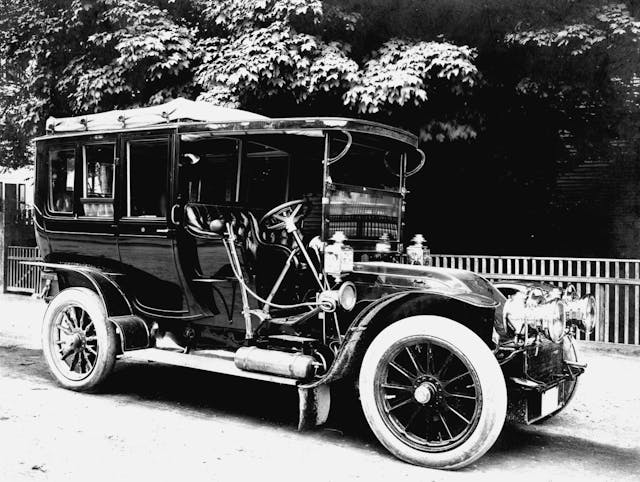

Their next car, however, was not at all typical. The 1906 Charron-Girardot-Voigt (CGV) was almost as much early motorhome as it was early motorcar. The Andersons commissioned it with long-distance travel in mind, and its build was exciting enough to prompt an announcement in a French newspaper, which called it “the most comfortable and most elegant automobile one could imagine.” The rearmost seat converted into a bed, and two smaller seats flipped up for a wash bin. Since these were the days before interstates and rest stops, there was a toilet as well. With dual chain drive and a 75-hp T-head four-cylinder engine, the car could do 75-to-80 mph despite its immense size.

The CGV was the Andersons’ most expensive vehicle: It reportedly cost $23,000 to build. The Ford Model T, introduced a few years later, cost well under $1000. To be fair to CGV, though, Model Ts didn’t come with a toilet.

By 1907, Larz’s 1901 Winton Bullet would have already been obsolete in terms of high performance, so that year while on vacation in Europe he bought a Fiat and had it bodied in New York. The 11-liter, 65-hp six-cylinder made it one of the fastest cars money could buy in 1907, so the Andersons nicknamed it “The Conqueror” with the motto “No Hill Can Stop Me.” An odd flex today, but hills stopped many a motorcar in the 1900s. They again followed up a sporty purchase with something completely different in 1908—a Bailey Electric Phaeton Victoria. With an open body resembling a carriage and early collaboration with Thomas Edison, Baileys were built in Massachusetts and boasted 100 miles of range. Early electrics were often marketed to women because of their ease of operation, and the Bailey was Isabel’s favorite car. Its nickname was “The Good Fairy;” its motto was “Always Ready and Faithful.”

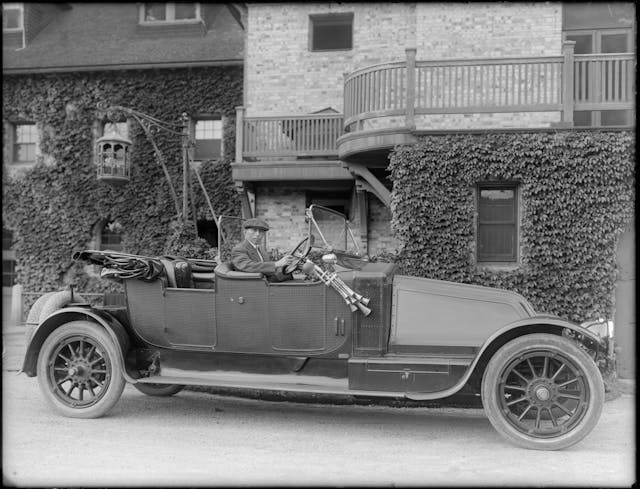

The Andersons went back to the French for their next car in 1910—a Panhard et Levassor—as a formal landaulet city car while Larz was at his diplomatic post in Belgium. In 1911 they bought an example of the Harry Stutz–designed American Underslung, which was noted for its distinctively low chassis and marketed as “The Car For the Discriminating Few” (the American Underslung passed into Briggs Cunningham’s ownership in the 1940s). They went French again in 1912 with their Renault Victoria Phaeton, distinguished by its sloped nose, radiator placement behind the engine, brass accents, and special canework on the sides of the Vanden Plas–built body. A similar Renault went down with the Titanic that same year.

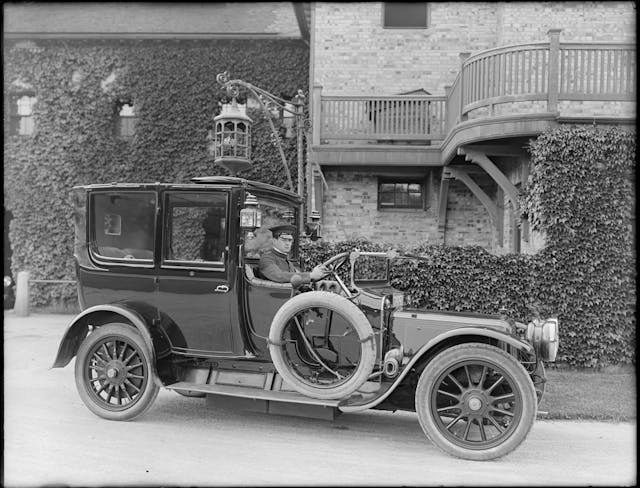

In 1915, the Andersons acquired a Packard Twin Six. In a time when even high-end cars had six-cylinder engines, Packard introduced the first mass-produced 12-cylinder car. Bodied by Brewster & Co. in New York with fairly conservative sedan coachwork, Larz and Isabel bestowed upon theirs the appropriate nickname of “12 Apostles.”

Their Cars, Post-World War I

After the war, when Isabel returned from Europe, their car-buying habits changed. The Andersons chose vehicles that were more conservative in style, with more muted colors and a more utilitarian nature, including multiple station wagons and trucks. The vehicles were generally less flashy and the Andersons were less likely to keep them.

Among the ones they did keep was a 1924 Renault Torpedo that, in contrast to their grand coachbuilt Renault from 1912, was a tiny and lower-priced open car. Next was a 1925 Luxor, built in Massachusetts. Luxor was not a luxury carmaker, and indeed Luxor configured almost all of its cars as taxis. The Andersons may have been the only people to order one for personal use. The final car that still remains with the Anderson collection was the 1926 Lincoln, an expensive car at $5300 that nevertheless wore a conservative sedan body and, like the Renault and Luxor, modest all-gray paint. As a nod to the 16th president, the Andersons nicknamed it “The Emancipator.”

Their Cars as a Collection

Larz died in 1937 at age 71. Isabel donated Anderson House in Washington, DC, to the Society of the Cincinnati (sort of a male equivalent to the Daughters of the American Revolution), and the house still serves as the organization’s headquarters. Meanwhile, she retired to the Brookline estate and seriously reduced expenses. According to their biography, Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age, the estate’s annual budget shrank from $220K to $77K a year. Naturally, the lavish gardens wilted a bit and the majesty of the place diminished. She did not even consider, however, selling off the group of early motorcars, even though many were not in use.

When Isabel passed in 1948, she willed the estate to the Town of Brookline. Unable and unsure how to maintain the entire property, the town turned it into Larz Anderson Park while the mansion, after some years of disrepair of vandalism, was torn down in the 1950s. The carriage house, meanwhile, was still gorgeous. The town turned over its contents to the Veteran Motor Car Club of America (VMCCA), which opened a museum there in 1948 and used the carriage house as its headquarters until 1966. Prominent early collectors like Henry Austin Clark and James Melton were members at the time. Today, 14 of the Andersons’ exceedingly rare, all-original, single-owner, single-home automobiles make up the permanent collection of the museum, which has become a regional hub of automotive culture and pursues its mission of “supporting the community through educational outreach and the preservation of our permanent collection of early automobiles.”

Appreciation for early automobiles and early car collecting started to take off in the 1930s and the post-World War II years. The VMCCA was founded in 1938. The Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA) started in 1935 and the Classic Car Club of America (CCCA) in 1952, and judged car shows with both clubs grew in popularity during the 1950s. As early as the 1920s, though, the Andersons were already opening up the carriage house for tours and viewings of their “ancient” vehicles. Their originality and preservation were valued long before preservation became a prevailing trend in the collector car hobby, and they were carefully kept even though there was yet little interest in early pioneering automobiles. Evan Ide, in The Stewardship of Historically Important Automobiles, writes that “Isabel spoke of the fact that nearly all styles and types of early car were represented, and that the overall collection told the story of the development of the motorcar.”

Indeed, the automobile advanced more rapidly in the early 1900s than at any other time. Today, a 15-year-old car is still perfectly usable. In 1920, a 15-year-old car was completely outclassed and obsolete. For the Andersons to keep and maintain their early cars was both incredibly forward-thinking and a great service to this little hobby of ours. Thank goodness they did.

A large part of the cause for Mme. Anderson cutting back on her upkeep budget, was the post Golden Age exorbitant taxes passed by the US government. In the previous Golden Age years, if you earned $100.00, you ended up having $100.00 in your pocket or portfolio. The US government’s penchant for taking Other People’s Money, resulted in many of the cottages in Newport which were built for Millions of dollars, subsequently being sold to the bourgeoisie for $25,000.00 who converted the mansions to boarding houses. Many were torn down because of the high cost of upkeep. Fortunately, Newport had some intelligent people left who could see the value of saving our history.

“….the Society of the Cincinnati (sort of a male equivalent to the Daughters of the American Revolution)……”

And all this time I thought the SAR (Sons of the American Revolution) was the male equivalent to the DAR.

I’ve been to events at Anderson House in Washington. It is incredibly ornate and opulent… even compared to the Phillips Collection mansion across the street. It’s only through this article that I’ve made the connection to the Boston museum… what an amazing story.

Wonderful article about a very unique and historical car collection. I have been several times and also attended car shows held on the museum grounds when I lived nearby. A wonderful experience!

About nine years ago we were planning a trip to the Boston area in our motorhome. As I usually do when preparing an itinerary, I looked up things to do in the Boston area. One of those “things” was the Larz Museum. I had never heard of the place but decided that it would be worth a visit.

It far exceeded our expectations. The cars were so interesting and were in the same condition as when they were parked in the carriage house. Being RV’er’s, the car with the toilet caught our attention.

I attended a car show there a few years ago. Came away thinking that it was the perfect venue for a car show. No sun heated asphalt to suffer through, just a lot of grass and areas of shade. The carriage house was a learning experience. I guess I have been lazy to not learn of its history. Never gave it a second thought. It was basically a car show within a car show. This article opened my eyes. Very interesting and educational. Thank you!

Dan- After the tragic lose of Penn Station in 63 the need to preserve classic American architecture went to the forefront. Grand Central ,as an example, was soon after saved as a direct result. Then fully restored. The benefits of saving these spaces are apparent to most everyone. We’ve learned. Today you can spend an afternoon on The High Line in the city ,which was once just an old abandoned railroad route, but is now an absolute gem .

Two thumbs way up. Thanks, Paul.

For me, a beautiful story, one of my favourite places.

Growing up in Boston suburbs, this was a visit several times a year, esp, the monthly events:

British Car Day, Studebaker Day, European Motorcycle Day, Muscle Car Day, German Car Day, etc.

Yes, in the original collection, we would always check out the “car with a toilet”, and yes, a real porcelain fixture (left rear corner, about 3′ off the ground, left rear door (like panel truck) swung out for access.

That vehicle was 8 feet tall!

The park, the grounds, the view, a place for a good picnic, “parking”, kite & rubber band airplane flying, fireworks…

It was a cool place & one of our family’s favorite visits.

The museum building still looks so majestic!

This is a great detailed story. I love Cars and Coffee and other events hosted by the Larz Andersen Museum They’re a must for auto buffs. We here in the Boston area are fortunate to have this resource and another worthy of a similar article, The Collin’s Foundation in Stow, MA. A currently growing private collection of astonishing scale, starting with a 1901 Oldsmobile Curved Dash Model R and other bronze era queens through the gamut including many Indy 500 cars.

Best article I’ve ever read on Hagerty’s site, so very interesting. Bravo, well done!

I second your comments Bobby!

I shook hands will Phil Hill on the LaMans track in 1962 at the time of the 275 GTO.