Wrenchin’ Wednesday: Fooling your project’s brainbox

Sometimes you’ve got to be smarter than what you’re working with. Working around EFI systems, for example, requires a certain type of cleverness.

An ECU has dozens of complex sensors, but many operate based on a simple principle of resistances. These sensors rely on a reference voltage that the ECU provides, with a unique value that corresponds with a specific measurement—temperature or oil pressure, for example. What if we could use this situation to our advantage, tweaking the voltages to trick the ECU into thinking it’s reading what we want it to? With that capability, we’d have a handy tool to use for engine swaps that require the factory gauges to read a foreign sending unit, or to eliminate systems like GM’s classic skip-shift.

Back when I replaced the injection pump on my 1996 Suburban K2500, the final step in the job required me to prepare the ECU for a relearning procedure that recalibrates the injection pump’s timing to account for any deviation in alignment during install. The process requires that the engine coolant be warm before turning the key to the off position and holding the pedal down; it’s something like a secret handshake that tells the ECU to erase its previous Top Dead Center Offset (TDCO) calibration and begin relearning a new position. The catch-22 with diesels is that in some conditions, it can be difficult to achieve operating temperatures during winter, and such was the case for this Suburban’s 6.5-liter turbodiesel. Sure, I could get into the 180s Fahrenheit with the Chevy in motion, but as soon as the engine had a moment to idle, the coolant temps dropped like a rock just below the 180-degree threshold required to allow for the TDCO reset.

Enter the home-brew solution: a coolant temp fooler. It’s a plug-in resistor pack that tricks the ECU into reading a coolant temp that’s above the necessary threshold to begin the TDCO reset, allowing the truck to be driven safely under full boost as the injection timing will be correct.

Whether you’re faking a coolant temp sensor like in today’s Wrenchin’ Wednesday, or eliminating a solenoid—such as a skip-shift or boost control unit—the goal is to find what resistance best replicates the intended target. For the coolant temp sensor, I noted that unplugging it dropped the ECU’s reading to -40 degrees, the floor of its range, which suggested that higher resistance equated to a colder value. (The open circuit read as the equivalent of an incredibly high resistance.)

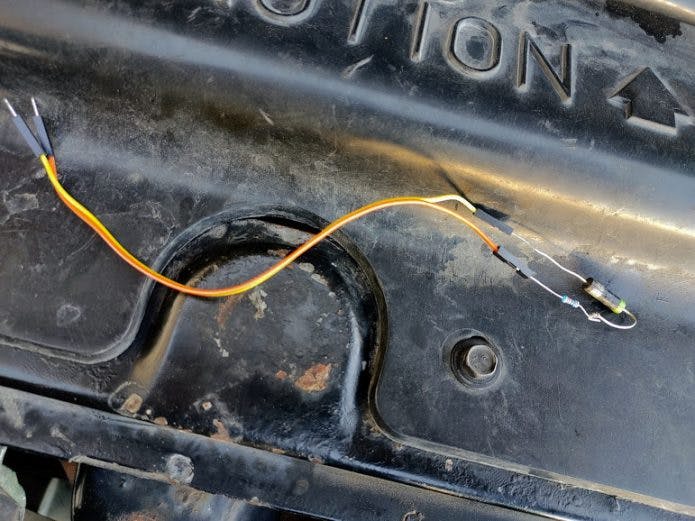

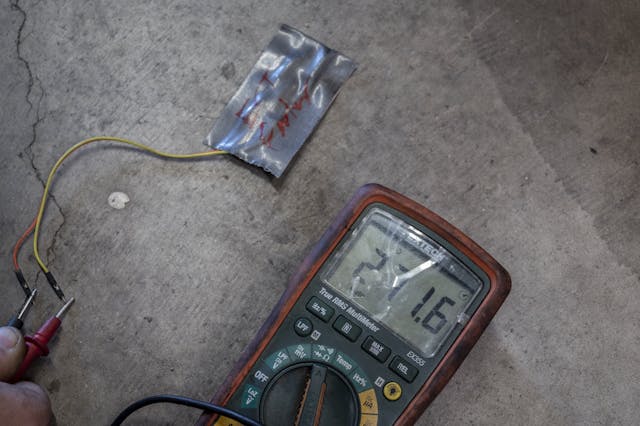

Starting with a typical 1ooo-ohm resistor, I was able to guess and check different combinations of resistors to Goldilocks my way to an ideal combination that would trick the ECU into reading a value just north of its 180-degree threshold for the TDCO reset. The happy place was with these two resistors totaling 275 ohms. Because this situation wasn’t going to be a regular occurrence, I just twisted the resistor’s legs together and used breadboard jumper wires to build a tool without soldering, but if you were looking to use such a device repeatedly, I’d permanently recommend hard-wiring everything. You can also measure the resistance across the sending unit at the engine’s current conditions to get a starting point based on the value it’s currently seeing.

For something like a solenoid delete, you’ll have to determine the load resistance by measuring the voltage and current draw of the solenoid’s trigger coil, then divide the voltage by the amperage using Ohm’s law to figure out the resistance of the coil when energized. By matching your resistor pack in this manner, you can trick many ECUs into thinking that all systems are normal, preventing a check engine light or unintuitive skip-shift. Many of the aftermarket solutions that you can purchase online are just resistor packs wired with factory connectors, so the best solution is often a judgement call between whether or not you have an assortment of resistors on hand, the time to reverse-engineer the component you’re trying to replace, and the price of someone selling a prepackaged solution on eBay.

Another use for this skill is to match sending units from a swapped engine to the factory gauges in your project car. Whether the scale pans out will be to a case-by-case situation, but you can calibrate a traditional analog temperature sending unit by wiring a resistor in series with the signal wire to adjust its “zero” point.

Try this method yourself the next time you need to manipulate an ECU to do your unconventional bidding. It can save the day for just a few cents in parts.